This is the first of two excerpts from La Cochinchine française (1883), one of several works on colonial Indochina written by Saigon magistrate Raoul Postel.

The European City: Saigon

The name “Saigon” was improperly given by the French to the capital of their colony. The Annamites [Vietnamese] designate it as Ben-Thanh, or alternatively Ben-Nghe. Saigon is, in fact, the true name of the Chinese city of Cholon. We muddled up these names without cause, just for the sake of creating something new.

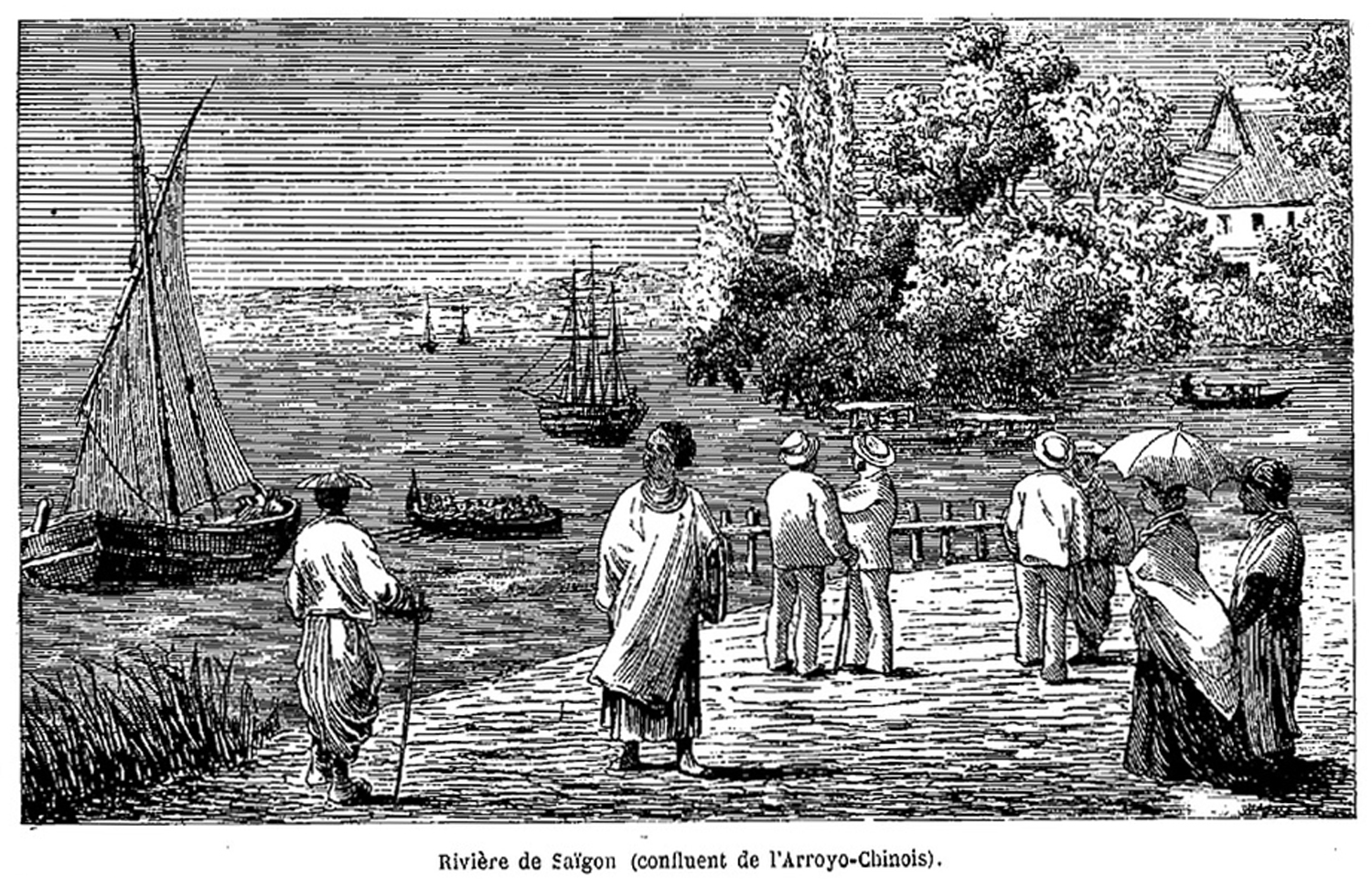

Saigon harbour in the early colonial era

The land area within the city limits is extremely large. Admiral de Lagrandière dreamed of a city with a core population of 500,000 souls, but his grandiose plan has not yet been realised. Although Saigon increases in size day by day, and has experienced particularly rapid growth over the last eight years, I can’t believe that the current city, including the many villages which border it on all sides, contains more than 115,000 individuals. In my view, the more narrowly-defined “European city” has no more than 30,000 inhabitants. It is true, however, that it is very difficult to quantify the Annamite and Chinese populations, whose records are poorly kept.

I will concern myself here only with what may be called the “white man’s city,” leaving the suburbs with their teeming oriental populations for later discussion. This European Saigon is enclosed in a square formed by the Don-nai [Saigon] River to the east, the arroyo-Chinois [Bến Nghé creek] to the south, the arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghè creek] to the north and the Canal de ceinture [Belt Canal] to the northwest, the latter connecting the two arroyos. Needless to say, the vast area of land between the Palace of the Government and the Canal de ceinture remains uninhabited, and will perhaps never be fully populated.

On the Don-nai River, just downstream from the mouth of the arroyo Chinois, stand the offices of the Messageries maritimes shipping company. On the other side of the arroyo, situated on the tree-lined quayside, one may find the Directorate of the Commercial Port, and in the Hôtel Wang-Tai, the Town Hall and the Commercial Court. After that there is a long line of restaurants and cafés, and, further up river, the Naval Port Directorate, the shipbuilding yards and the floating dock.

The Grand Canal [Nguyễn Huệ] pictured in 1882, bordered by rue Charner and rue Rigault de Genouilly

While the rue Charner is occupied only by French, Chinese or Malabar traders, the rue Rigault de Genouilly also includes the residence of the Commissioner and the former offices of the Regulator. Each of these streets has, in addition, a branch of the Auction House. The upper part of the Grand Canal has been filled, and in its place has been built a vast square dominated by a bandstand, where music can be heard several times a week.

Also on the rue Charner are the City Market and the very modest Cathedral. Most of the streets in the area behind these two monuments are occupied almost exclusively by industrious Asians, except for the rue Mac-Mahon, where one may find the most beautiful house in the city, occupied almost entirely by European traders.

To the right of the rue Rigault de Genouilly, running parallel to it but of greater length, is the rue Catinat [Đồng Khởi], a bustling entrepôt of both European and native traders which was once the main thoroughfare of the Annamite city. Also in the same direction, one may find the rue de l’Hôpital [Thái Văn Lung] and the rue de Thu-Duc [Đông Du], the latter leading to the vast buildings of the Naval Arsenal and beyond it to the grandiose constructions of the Sainte-Enfance [St Paul’s Convent].

The Sainte-Enfance (St Paul’s Convent) in the early colonial era

Close to the Sainte-Enfance are the Carmelite Convent, the Mission and the College d’Adran. Behind these institutions are the Botanical and Zoological Gardens, the intelligent and learned director of which, Monsieur Jean-Baptiste Louis-Pierre, has transformed it into the true rendezvous of all specimens of trees, shrubs and flowers from Indochina.

All this is, strictly speaking, the ville basse (lower town). Here one may find only small houses, with little or no garden spaces other than those of the Sainte-Enfance, the Mission and the Collège d’Adran, which are all splendidly laid out. The lower end of the rue de l’Hôpital [Thái Văn Lung] is still a swamp, while the area west of rue Mac-Mahon presents the same spectacle, with forlorn clumps of trees protruding from marshland. These two areas are quite unhealthy.

I mentioned that the ville haute (upper town) begins at the rue d’Espagne [Lê Thánh Tôn]. This is the luxurious European quarter, the leafy “aristocratic district” of the city. There are no trading houses, no indigenous people and no Malabar or Chinese in this area – it is inhabited entirely by “palefaces.” Since there are no streams or wetlands here, the air is clean and healthy. Each house has its own pretty garden. The offices of government administrators in the upper town are also more spaciously built, forming a huge contrast to the meagre barracks which were provided in the lower town during the early years of the colony.

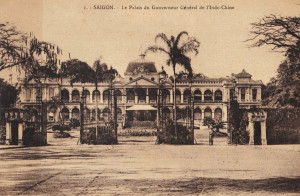

The ville haute (upper town), described by Postel as the luxurious European quarter, the leafy “aristocratic district” of the city

Running parallel to the rue d’Espagne is the rue de Lagrandière [Lý Tự Trọng]. Located on the right side of this street, as we travel in the direction from Cholon to the Botanical and Zoological Gardens, are the Prison, the Courthouse, the Attorney General’s office, the Telegraph administration, and the offices of the Direction of the Interior. On the left side of the street, heading in the same direction, are the Gendarmerie, the Observatory and the Military Hospital.

Three great arteries intersect the upper town perpendicularly: the rue Pellerin [Pasteur], at the centre of which one may find the Bishop’s Palace; the rue Catinat [Đồng Khởi], which contains the Direction of Roads and Bridges, the Land Office, the Directorate of the Interior, the Treasury and the Post Office; and finally the rue Nationale [Hai Bà Trưng], on which are situated the Council of War building, the former Palace of the Government, the National Printing Works and the Officers’ Mess. Finally, please note the newest government office, that of the Regulator, on rue Tabert, the street which runs parallel to rue de Lagrandière.

It remains for me to mention the principal building of the colony, the Palace of the Government, located alongside the Route stratégique from Saigon to Cholon, behind which is the beautiful Jardin de la ville (City Park), where military music may be enjoyed every Thursday evening. On the other side of the Route stratégique is the Plain of Tombs, which will be described elsewhere.

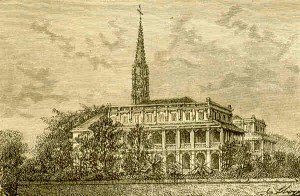

The Palace of the Government in the 1880s

The Palace of the Government has an imposing appearance. However, this immense building serves only to house the governor and his two or three aides-de-camp. Yet it cost the colony a dozen million francs! This was one of those ruinous fancies, useless and motivated only by the vain whim of a previous governor.

A final word about the port. Although it may not yet be compared to the wonderfully animated harbour of Singapore, our port of Saigon is no less frequented by many ships of all shapes and from all sources. These include Malay prahos and lorchas, Chinese and Annamite junks, warships of the various European nations which maintain colonies in the Far East, trading vessels flying all the flags of the world, and passenger ships and steamers heading for multiple destinations. It’s a real hive of activity, the contemplation of which has always fascinated me.

What surprises Europeans the most is the design of the Asian boats which we see here. What strange machines they area, these vessels which are still built to ancient plans using techniques which have changed little down the centuries. Take, for example, the Chinese junk. Anyone who hasn’t seen one could not imagine what an inconvenient piece of apparatus it is. Massive, heavy and square, it has wooden anchors and each of its four tall masts is made from a whole tree. Huge eyes, symbolising the vigilance of its captain, are painted in bright colours on its bow. The stern, which rises above the water as high as the châteaux-d’arrière (stern castles) of our older vessels, is also decorated with paintings; here one can often make out the image of a huge eagle with outstretched wings.

A typical Chinese merchant junk of the late 19th century

Inside the junk, the clutter is simply indescribable. Not an inch of space is wasted, but if we try to walk from one end of the junk to the other, we do not know where to place our feet and the journey is literally fraught with obstacles, to the extent that one wonders what maneouvres are possible at sea in the midst of such disorder.

Even the smallest gaps are packed full of goods. As for the passenger accommodation, every tiny nook, however exposed, is equipped with matting or hammocks and crammed so full of people that it is hard to understand how they avoid being swept overboard during a sea crossing.

Only two spaces are respected within the junk: the kitchen, a spacious area at the centre of the ship, which is a theatre of incessant activity; and the stern castle, a monumental fortress that contains the crew’s weapons and ammunition, along with the shrine of a portable deity, before which fragrant jossticks are burned.

One wonders how this machine, seemingly devoid of all nautical qualities other than strength, can accomplish its double pilgrimage every year with so few accidents. The view of the land is the only guide to navigation. Thanks to long practice, the pilot is always familiar with every detail of the coast. This is very fortunate, because the compass – the discovery of which counts among the few maritime claims of the Chinese – is used very little. Indeed, I would venture to suggest that no Chinese crew has any understanding of it; it is only the confidence and willpower of these bold sailors which saves them from disaster.

Merchant shipping on the arroyo-Chinois

Some of these Chinese junks measure as much as 700 tonnes, but their average size is 300 tonnes. In China they cost around 75,000 to 80,000 francs to buy. Malay and Annamite vessels hardly differ from the Chinese model.

The cries and songs of the junk crews are impossible to recreate. One could describe them as sounding like a squad of screaming demons.

Needless to say, here in Saigon the Asian boatmen operate within limits which have been specifically determined for them: the arroyo-Chinois belongs to them. And it is in this area that all trade with the interior is focused.

Such is Saigon today. How to predict its future?

Saigon is a newly-created city and should therefore not be compared with the ports of neighbouring European colonies. What we are aiming at is to establish a compact, homogeneous source of wealth, useful above all to our Métropole. To us this seems preferable to an agglomeration of 20 different races, based solely on domestic trade, without proper resources and subject to all the dangers of a distant war. This is our avowed aim: but are we succeeding?

Another view of Saigon harbour in the early colonial era

From a purely physical point of view, responding to those who compare Saigon unfavourably with Singapore and regard our new city with disdain, one must point out that, 22 leagues inland, we can’t all of a sudden build a city as monumental as one which already has over 40 years of existence and sits happily on the seashore. Of course the coup d’oeil here is not yet as satisfying as it is in Colombo or Singapore. We are still in the work of raising our child.

However, consider what Saigon was like 15 years ago, when swamps covered one part of the city and a vast cemetery occupied the remainder, both giving off a formidable odour during the rainy season. Not to mention the poor stilted houses which once served as residences for all French colons. Now consider what has been done since that time – the filling of the canals, the construction of roads and bridges, the great colonial buildings which have sprung up everywhere, and the elegant upper town which has grown as if by magic. We cannot ignore the achievements of recent years, notwithstanding the complaints of those envious people who seek to undermine our progress to date.

In a few years time, our Saigon will lack nothing in comparison with those other proud Asian port cities. We have already achieved a great deal and we will achieve more, because we are still far from reaching the point at which our path of expansion is complete. Already, construction has begun in the area around the ancient citadel, and the trowel of our developers now begins to threaten the bushes of the Plain of Tombs. This is not a sign of decadence.

To read part 2 of this serialisation, click here.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.