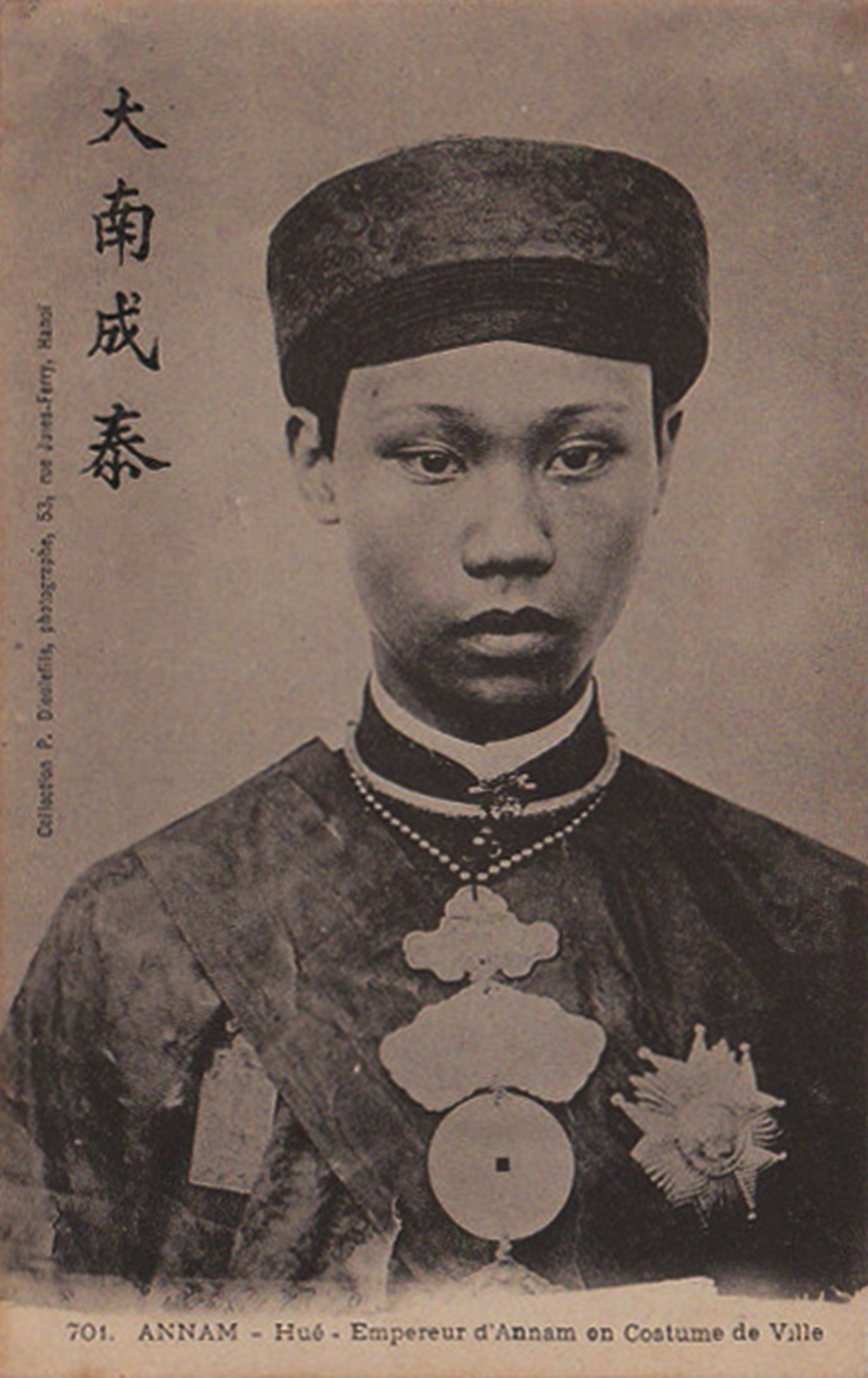

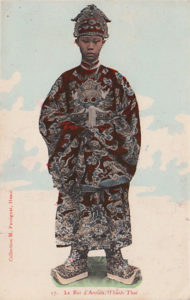

Emperor Thành Thái (ruled 1889-1907)

Nguyễn dynasty Emperor Thành Thái (ruled 1889-1907) is often remembered at best as eccentric, at worst as mentally unstable. Some historians have claimed that his madness was fabricated by the French in order to diminish his authority. Others have suggested that Thành Thái himself feigned madness in order to confuse the French. While there may be good reason to doubt some of the more lurid accounts of Thành Thái’s behaviour, it’s clear that his “abnormal temperament” manifested itself from an early age, and that by 1907 it had precipitated a serious constitutional crisis at the court of Huế.

Here is a selection of contemporary descriptions of the events leading to Thành Thái’s eventual detention and removal from the throne.

Nguyễn Phúc Tộc Thế Phải (Nguyễn Phúc Family Genealogy), Hội Đồng Trị Sự Nguyễn Phúc Tộc, 1995

“He was intelligent by nature, but his temperament was abnormal, he sought debauchery and rarely listened to those trying to dissuade him; on many nights, he would ride his horse out of the Citadel seeking pleasure, and nobody stopped him. Because of his temperament and behaviour, in the third month of the Quý tị year [1893 – Thành Thái was then aged just 14], government mandarins had to seek permission from the Queen Mothers’ Palace to rest his troubled mind at the Bồng Dinh Palace on Tinh Tảm Lake.”

Excerpt from Henri Turot’s “Indo-Chine, Philippines, Chine, Japon: d’une gare à l’autre,” 1901

A curiosity of Cholon is the elegant mansion of the Phu (prefect), where lovers of culinary peculiarities will be initiated into the complicated mysteries of Annamite cuisine.

The Phu also has two very sweet daughters, each with her own story to tell.

One was formerly in love with a young officer who died unexpectedly before the nuptials, and whose tomb is piously maintained by the Phu. The other had the good fortune to attract the attention of the young Emperor of Annam when he came to Saigon to visit Governor General Paul Doumer. It’s said that at nightfall, the Asian sovereign jumped over the wall of the palace, where he had been offered rather formal hospitality, and made his way to Cholon to engage, under the window of the Phu’s daughter, in manifestations incompatible with royal majesty. M. Doumer, who does not take such matters lightly, was called to come and put things right.

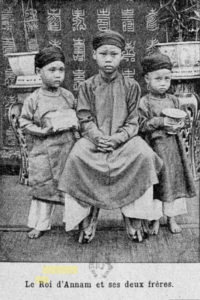

A young Emperor Thành Thái (ruled 1889-1907) with his two brothers, from Quelques notes sur l’An-Nam, L. de Sainte-Marie, 1895

“Le Roi d’Annam” (The King of Annam), in La Croix, 5 October 1906

The Courrier d’Extrême-Orient, which arrived yesterday in Marseille on the ship Calédonien, has provided us with the following account, which is reproduced here with the most express reservations.

“The old palace of the kings of Annam has been the scene of a new act of madness by Thanh-Thai. Recently, with the return of his bloodthirsty fantasies, this prince killed some of his women, in circumstances which displayed the heinous and dangerous state of mind of the master of Annam. Now, the king has murdered with a revolver the prince president of the Council of the Royal Family. The victim, who enjoyed general respect, was already of great age, with him was extinguished the last son of the Emperor Minh-Mang.

Afterwards, the king locked himself in his private apartments, refusing to receive the Résident supérieur, that is to say an act which is considered an affront against the representative of France in Annam. His own ministers also were the object of a similar exclusion.”

“La Folie d’un Empereur” (The Madness of an Emperor), from Le Progrès, 3 July 1907

There’s currently a great deal of talk in colonial circles about the sanctions which will be imposed in response to the lamentable excesses committed by the Emperor of Annam.

Thanh-Thai, who only last year was received with great pomp and ceremony in Hanoi, has become mad. In his own palace he has committed cruelty on the people around him reminiscent of that of the decadent Roman emperors. One of his wives was delivered naked to tigers, others were riddled with bullets, others tortured in a hundred abominable ways: In truth, it’s already a few years since Thanh-Thai, obviously suffering from some physiological defect, began to indulge in this kind of bloodthirsty sadism. We were able to recognise in him some traits which left no doubt in this regard. We knew that he has always rebelled against any moral direction. When M. de Lanessan was Governor General of Indochina, Thanh-Thai, then barely 15 years old, already had a harem of a dozen women. One of them, the daughter of one of his ministers, exercised great influence over his mind and ruled him entirely through the senses, pushing him to the most culpable wrongdoing.

M. de Lanessan recounted how that intriguing minister had himself thrown his daughter into the arms of the emperor, the better to establish his authority in Hue. His plan was to get rid of the Queen Mother, and once that unwelcome guardianship had been discarded, to seize power entirely for himself.

During a trip to Hue, M. de Lanessan had the occasion to get to know Thanh-Thai. He struck the Governor General as being like a little boy, capricious but intelligent. Yet he seemed ignorant and badly brought up. M. de Lanessan admonished him severely about his conduct.

Jean Marie Antoine de Lanessan, Governor General of Indochina 1891-1894 (Photographie Marius)

But already, to another resident of France who had previously made similar representations to him, the young emperor had answered: “Why are you criticizing me? It was you who raised me.”

It’s unfortunate that Thanh-Thai never received a proper education and that while he was still young he was abandoned to the violence of his perverse instincts. Following the admonition of M. de Lanessan, he promised to correct his flaws. But scarcely had the Governor General left than the young sovereign resumed the course of his vicious life.

Thus, over a long period, were the pranks, the eccentricities and the criminal follies of this degenerate kept secret. The old mandarins of the court knew them so well that they had gave Thanh-Thai only their official deference. The old Queen Mother deemed the problem so severe that she was always opposed to his freedom.

What is new is the sudden fuss which is now being made about the excesses of this unbalanced prince, given that in the past everyone seemed content to deplore his activities in silence. The result of the publicity surrounding his behaviour is that the emperor was submitted to an examination by doctors, who declared the “non-accountability” of the sovereign.

Thanh-Thai has been detained in his palace so that it is impossible for him to cause any further harm. What should be done now? M. Beau, the current Governor General of Indochina, has studied this question and the Minister of Colonies has given him full powers to resolve the issue.

Several solutions come to mind. Whatever course of action is decided, it is very important that the government of the French Republic remains in the background as much as possible, or at least gives the appearance of so doing, and that it is seen to yield in accepting the pressure of the court, of the Co Mat (Council of Ministers), the literati.

This much is certain: Thanh-Thai is already discredited in the eyes of the Annamite people. Since the day he appeared in a chauffeur’s costume, hair cut short under his cap and large dark glasses on his nose, driving a motorcycle furiously, he was lost to them.

Accustomed to see their rulers only from afar and in a setting of apotheosis, with their chignons gathered on their heads, advancing majestically in silk robes, the Annamite people have only the most profound contempt for an emperor who drives around the streets, exposing himself to all curiosity, to all the familiarities and taunts of the crowd.

Thành Thái and his brother in 1900

If, thus, the emperor were to be deposed, his disrepute is such that the people will likely do nothing to restrain the hand which removes his crown.

If approached by the Governor General, members of Co Mat of the Annamite empire will surely not be far from seeking his deposition. But it is understandable that M. Beau does not wish to approach them until all the ministers are fully agreed on this matter.

Another solution would be to consult the people by way of referendum. But it seems a priori difficult to organise such consultation.

In addition, once the emperor has been deposed, should we replace him or should we instead abolish the monarchical principle in Annam? Paul Bert already considered such abolition, several years ago, giving thought to the idea of equipping the country with parliamentary institutions. There is no shortage of scholars who would support a move in this direction. But what would the people think of a solution which, in depriving them of their sovereign, removes the religious leader of Annam?

More numerous, it seems, are those inclined to replace the deposed sovereign. But then the question arises regarding the choice of successor. With whom should we replace Thanh-Thai? Most would argue that a prince of the imperial line should be called to the throne. Some have already posed the candidature of Ham-Nghi, who has now lived for several years in Algiers. But we oppose this candidacy, on the grounds that Prince Ham-Nghi, having married a French woman, would have no influence over his people from the religious point of view, and would only cause us serious embarrassment.

In the meantime, M. de Lanessan has asked the Queen Mother to issue an edict dispossessing Thanh Thai of his prerogatives and investing all royal powers in a Regency Council. Thanh-Thai, confined to his palace, may one day be cured of his madness. In any case, being isolated, he will be harmless.

M. Beau is currently studying these various solutions. What is important, regardless of the decision taken, is that the Co Mat is seen by the Annamite people to assume all responsibilities for that decision.

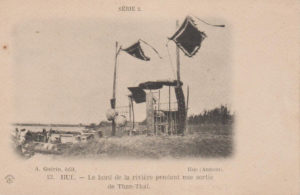

Riverside decorations in preparation for a river trip by Thành Thái

“L’empereur d’Annam” (The Emperor of Annam), in Bulletin de la Société de géographie commerciale de Paris, August 1907

The Emperor of Annam, Thanh Thai, having indulged in numerous acts of violence which denoted a veritable intellectual impairment, obliged us in 1906 to impose certain monitoring measures to prevent the recurrence of his deplorable excesses.

However, we have recently had to reach a more rigorous decision regarding him.

On 30 July 1907, the Résident supérieur arranged for the detention of the emperor in his palace and the setting up of a Council of Regency to take charge of affairs under the control of the Résident supérieur.

A phantom of a sovereign, Thanh-Thai was only a hieratic idol, dressed in yellow silk; he never took active part in the government.

“l’Intèrnement du Roi d’Annam” (The Detention of the King of Annam), in Journal des débats politiques et littéraires, 2 August 1907

Readers will recall that in the month of August 1906, after Thanh-Thai, King of Annam had indulged in many acts of violence, veritable movements of madness caused by habitual debauchery, the Résident supérieur was obliged to take, with the Co Mat (Council of Ministers), measures to put an end to the king’s scandalous conduct.

Since that time he has been monitored constantly, and for a while it seemed that he had returned to a state of reassuring calm. But towards the end of May 1907, the mandarins placed at his side expressed concern about some changes in his manners, some alteration of his features, outward signs by which, periodically, his acts of madness were manifested.

Furthermore, the Résident supérieur had to be brought in to witness the awakening of the king’s bad instincts when he inflicted the most serious abuse on members of his entourage.

All of the facts and specific information gathered by the Résident supérieur now leaves no doubt about the disorder observed in the state of Thanh-Thai, on his recklessness and on the dangers of letting him continue to exercise royal power.

In these circumstances, the government recently decided that it was necessary to detain the king in his palace and to establish a Regency Council, composed of members of Co Mat and chaired by the Minister of Justice, under the overall and ongoing control of our representative in Hue.

Emperor Thành Thái (ruled 1889-1907)

In implementing this decision and in accordance with instructions of the Minister of Colonies, the Résident supérieur proceeded on 30 July 1907 with the detention of the king in his palace and the establishment of the Regency Council, which immediately took over the direction of royal affairs, under the supervision of the Résident supérieur.

The Governor General, in providing the information above, remarked that these measures were executed without any incident occurring.

“L’Empereur Fou” (The Mad Emperor), in Les Annamites: société, coutumes, religions by Colonel Édouard Diguet, 1907

The Emperor Thanh Thai will be deposed, but no one yet knows whether the monarchical principle in Annam will be removed or maintained.

M. Beau, Governor General of Indochina, has been concerned, since his arrival in the Far East, with the Emperor Thanh-Thai, who is now confined to his palace, out of harm’s way.

Members of Co Mat or Council of Ministers of the empire of Annam, when approached by the Governor General, were unanimous in asking for the mad emperor to be deposed. They have proposed as his successor a child, descendant of the Emperor Gia Long. The candidacy of Ham-Nghi, the dethroned former Emperor, was ruled out by the Co Mat, the latter having lost, through his marriage with a French woman, any link with his race; indeed, the return of Ham-Nghi would have been viewed very badly in Annam, where the prince is now considered a stranger.

M. Beau, before formally consulting the Co Mat, wondered if we might profit from the deposition of Thanh-Thai by abolishing the monarchical principle in Annam, and replacing royalty in this country by a sort of parliament. This is an old idea which Paul Bert came up with some years ago when he thought of creating in Hanoi a permanent Congress of all the Councils of Notables. A certain number of Tonkinese and Annamite scholars, those dedicated to civilising ideas, would not take a dim view of the introduction of such a parliamentary system in this country. But what would the people think of a solution which, by depriving them of their sovereign, removes the religious leader of Annam?

This issue is indeed very serious. M. Beau is studying it very carefully, and we know that the Minister of the Colonies has given him full authority to resolve it. It’s in Annam, and not in Paris, that this matter must be determined.

From all points of view, whether a new emperor ascends the throne in Annam or a parliamentary system is introduced, the fate of Thanh-Thai is in no doubt. This mad sovereign, when the issue is laid before the Co Mat gathered in solemn assembly, will be deposed.

Paul Beau, Governor General of Indochina 1902-1908

But it is understandable that M. Beau is prudent enough not to proceed until members of the Co Mat are all agreed on the correct course of action in retaining or abolishing the monarchical principle in Annam. – F H

“La Folie de l’Empereur d’Annam (The Madness of the Emperor of Annam), in La Lanterne: journal politique quotidien, 7 September 1907

The newspaper l’Opinion, while expressing reservations about this information, relates that a few weeks ago, the Emperor of Annam experienced an acute fit of madness, the tragic manifestations of which required the intervention of M. Lyce, Résident supérieur of Annam, who, if warned in time, could have prevented a scene of carnage in the palace of the young sovereign.

Armed with a revolver, Thanh-Thai rushed into the apartments of his concubines, and, at close range, allegedly killed three of his women. Continuing into the private apartments of high ranking concubines, he proceeded to tie up two of them, including the Empress herself, and whipped them until they were bleeding.

The Co Mat, which is the great Council of Ministers of the Annamite empire, moved by the demented attitude of the sovereign, has drafted a report containing eight complaints about Thanh-Thai, among which, apart from the above facts, is one very serious in the eyes of Annamites – bathing naked in the river of Hue.

Since ancient times, the Annamites, like their educators the Chinese, like to surround the majesty of the sovereign with a mysterious and divine character. It would have been clever of the French government to keep this character in the emperors we ourselves placed on the throne of Annam, those who had already committed, in the eyes of the people, the crime of being our creatures. But, like awkward and curious children, we broke the idol which represented the Annamite design of royal majesty. The Emperor Thanh-Thai promenades around the city on a bicycle, or in a Victoria carriage with one or two of his wives, thus exposing himself to a promiscuity which greatly undermines his prestige. What must his subjects think?

We could see the concern in their eyes at the 1897 celebrations in Saigon and at the Hanoi Exhibition in 1902. One whom the Annamite regards with not a shudder of awe, only a curious eye and a tad of maliciousness, cannot be his king. He thinks bitterly that we should have left untouched the majesty of the emperor, whose sovereignty we had already removed.

Emperor Thành Thái (ruled 1889-1907)

“L’Internement du Roi d’Annam (The Detention of the King of Annam), in La Quinzaine coloniale: organe de l’Union coloniale française, 1907

Thanh Thai, the King of Annam, has been detained by order of the government. One cannot say that this measure is a surprise. Indeed, it’s more than a year already since the government signalled its intention of taking this decision, and at that time everyone agreed with the idea, finding it amply justified by the scandalous fantasies and atrocities which surrounded the name of Thanh-Thai, both in his kingdom and throughout the Far East, an orgy of bloodthirstiness and debauchery.

However, under the influence of considerations whose value now escapes us, it was eventually thought better to give him the benefit of the doubt. Sadly, if we were hoping to see from the young king some kind of repentance, recent events have been quick to show that we overestimated his wisdom. After seeming, for a few months, to have mended his ways, Thanh-Thai returned to his bloodthirsty excesses.

This time, the government had to recognise that it was no longer possible, under pain of incurring grave responsibilities and provoking perhaps an uprising in the Annamite population, to continue to entrust the exercise of royal power to a sovereign who has, for his subjects, became an object of ridicule, disgust and hatred. It was therefore decided to detain Thanh-Thai in his palace and to establish a Council of Regency, composed of members of the Co Mat, which will operate under the chairmanship of the Minister of Justice and under the control our representative in Hue.

It must be said that the stern measures which have been taken to address the delicate and complex situation created by the state of dementia displayed by Thanh-Thai have not given rise to the slightest criticism. The constitution of a Council of Regency is viewed, indeed, as the only regular and normal way of ensuring continuity in the exercise of the royal function in a country where a sovereign who is unable to reign nonetheless remains invested with the title of king.

But isn’t it the case that press coverage of the events which have just occurred in Hue have been, if not inaccurate, at least incomplete on an essential point? When we telegraphed from Saigon that the king had been deposed without difficulty or incident, we purposely emphasised the word “deposition.”

The Đại Cung Môn, main entrance to the Forbidden Purple City in the Huế Citadel

This was to show that Thanh-Thai was not only seen to be removed from the exercise of power, but also that he had been deprived of the title and dignity of king. In other words, the government had opened the vacancy of the throne for an indefinite period, effectively removing the monarchy.

If that were so, this matter would be extremely serious. It would be nothing less, in fact, than a revolution in the inner constitution of the kingdom, a tacit abrogation by unilateral means of the conventions which govern the organisation of our protectorate in Annam and determine the nature of the relationship which binds the Annamite nation to France and its representatives.

One will understand, under these conditions, that a further explanation of the nature and scope of the measures taken by the government appear to us essential. We hope that those explanations will permit nothing to subsist of the hypothesis that we have issued. If it were otherwise, we can only regret a dangerous sudden change of course in our Indochina policy, by a measure imposed by no necessity.

Thai-Thanh himself, despite his follies and bloodthirsty extravagances, has never been an embarrassment to us; his detention has rendered him harmless, without any need to take away the title of king. If one decided to go that far, it could only be on the condition of nominating a successor immediately, who, whatever the choice of candidate, will not more seriously hamper our actions.

In short, whatever the personality of the sovereign, what is needed is to retain the monarchy, which in this country is little more than decor, facade, but a facade to which the Annamites are accustomed, an important component of their traditional institutions behind which our action is exercised with ease and freedom. Indeed, we could not exercise that action to the same open and convenient degree without the visual deception provided by this fiction.

We would like to think that the government does not think differently from us on this point and that the deposition of Thanh-Thai did not take place in way we have dared to imagine above. This is one more reason why the authorities must hasten to put things straight by means of an authorised communication which defines precisely the new situation created by the measures taken in respect of Thanh-Thai.

The young Emperor Duy Tân (ruled 1907-1916)

“Un Roi Fou” (A Mad King), in Le Journal, 7 October 1907

Thanh Thai has abdicated and it is the young Duy-Tan, aged only eight, who has succeeded him on the throne.

Marseille, 6 October – The newspaper Le Courrier Saïgonnais, which arrived this afternoon, gives the following details on the abdication of King Thanh Thai and the ceremony of elevation to the throne of his fifth son, aged eight, the second of his surviving children, who will reign as Duy Tan.

In the morning, in the presence of the Governor General and the Résident supérieur, various rituals took place aimed at choosing the regnal name of the sovereign and presenting the royal regalia.

Official receptions were held in the afternoon. The new king thanked the French government, in the person of the Governor General, for the support which it has always given to the kingdom of Annam. The Governor General responded with his wishes for the new king to enjoy a long reign and for the prosperity of Annam. Then, on behalf of the French government, he declared the recognition of Duy Tan and led him to the throne, accompanied by the Résident supérieur. The ceremony completed, the king accompanied the Governor General out of the throne room.

The next day, 6 September, His Majesty Duy-Tan, accompanied by members of the Council of Regency and senior mandarins of the court, visited the Governor General. The king again thanked the French government for the powerful support it continues to lend to Annam in all circumstances.

The President of the Council of Regency, on behalf of His Majesty, members of the Regency Council and the mandarins of the court, thanked the French government for agreeing to nominate a new king for Annam and giving the country a government in line with its Constitution.

Responding, the Governor General offered His Majesty Duy-Tan the best wishes of the government of the French Republic. “The protectorate government,” he added, “will partner Annam with great heart, as it has always done, supporting the work of moral and material progress. France will continue to offer all of its powerful assistance to the empire of Annam in order to avert the dangers of war, but it is necessary that the mandarins also bring us, from their side, the most dedicated assistance.”

After the visit, the king was taken to his carriage by the Résident supérieur. Military honours were rendered by troops of the garrison of Hue.

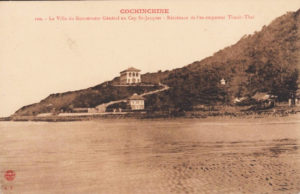

Thành Thái took up residence in Cap-Saint-Jacques after he was deposed

“L’empereur Thanh-Thai” (Emperor Thanh-Thai), in Les Annales coloniales: organe de la France coloniale modern, 31 October 1907

Thanh Thai, the former king of Annam, arrived this morning in Cap-Saint-Jacques on the steamship “Cachar.” He was accompanied by five women, 10 children, six nurses, a doctor and 20 servants. Disembarking at Cap-Saint-Jacques, he was received by the administrator of the province and an aide of the Governor General. The former king has settled provisionally in the villa of Governor General. The landing and reception did not give rise to any incident.

De Java au Japon par l’Indochine, la Chine et la Corée by A Maufroid, 1913

Do the Annamites glorify their future by building new tombs in memory of the sovereigns who have held the throne since our conquest? No, probably because in reality, since Tu-Duc, there have been no more all-powerful and respected Annamite emperors.

Can the Annamite recognise as their leaders puppets chosen by the French to govern in their name? Hiep-Hoa, and after him Dong Khanh, were humiliated by the invaders. Thanh-Thai in recent years was dismissed as a mere clerk. Without doubt, the excesses of Thanh-Thai brought a ferocious sadism. He cut the breasts of his women, climbed into the branches of trees and hunted them with the shots of his rifle, like birds.

But ultimately, it was above all his lack of docility towards the Resident Superior which motivated his exile in Saigon.

There, Thanh-Thai continues to live out his fantasies in a disorderly way. However, he seems to have become quite harmless. His last joke was to simulate a deep love for the daughter of the official responsible for monitoring him. Whenever that official presented himself to ensure the state of his charge, Thanh-Thai overwhelmed him with huge bouquets, destined for the lady of his thoughts.

Today, is the little Duy-Tan a true emperor to the Annamites? Certainly not; they know very well that this youngster of thirteen is, like his predecessors, a mere plaything in the hands of foreigners from the West.

His palace, by a curious irony, as is trapped in the citadel built in the eighteenth century by the Frenchman Ollivier for the great Emperor Gia Long. It looks a bit like the tombs scattered around the countryside of Hue. It is an immense dead city, surrounded by walls and ditches near the beautiful river with its transparent water.

Governor General Paul Doumer (1897-1902)

An excerpt from Indo-Chine française (souvenirs) by former Governor General Paul Doumer, 1930 edition

On the right bank of the Perfume River, where the king and his retinue disembark, waited a convoy accompanied by the huge elephants of the palace. One of them was coupled to a chariot of colossal dimensions, utterly out of proportion with the beast which dragged it. That chariot in which the king sat was painted with red lacquer and decorated with gold ornaments trimmed with yellow silk.

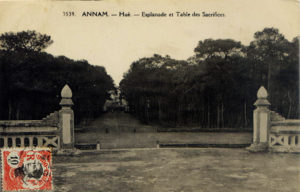

That was, I think, the last time, in 1897, that Thanh-Thai agreed to go to the Nam-Giao Esplanade in this manner. He later adopted, despite his mandarins’ protests that he should maintain the ancient traditions and rituals, a more simple and modern means of transport.

For Annamites whom European civilisation has not yet touched, the mass of elephants, the size and richness of the chariot well symbolised the royal power and majesty. It was bigger, in fact, that our small steel cannon up there on the ramparts, which could if necessary have swept aside all those processing along the long road with their elephants and altars. But that French cannon was not their enemy; it was their protector, which maintained the internal and external security of the kingdom, respected the lives, customs, beliefs and religious practices of the Annamite people, and was respected by all.

Good little cannon of France, stay on your high wall, silent, at rest, but always vigilant, always ready; the future of this country depends on it!

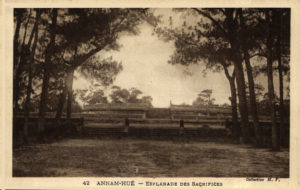

The Nam Giao Esplanade

The royal sacrifice to Heaven and Earth always takes place at night. The king, who in this ceremony assumes the office of high priest, prepared himself by fasting and meditating in a specially-built pagoda, located not far from the Nam-Giao Esplanade. He went directly there after leaving the palace. In the afternoon, he attended as a spectator the preparations, or more precisely the rehearsal of the massive and complicated ceremony to be staged that evening.

There, he gave me an appointment and, while his courtiers practiced the movements, dances and songs they would perform a few hours later, I had with Thanh-Thai, one on one, long conversations on over a hundred different subjects, which enabled me to obtain an idea of his character, his intelligence, his worth, his upbringing.

My judgment was subsequently confirmed during the five years I encountered him in his daily life, during which time, won over by the sympathy I showed him, he opened up to me and let me see the depths of his soul.

Thanh-Thai was not, to any degree, the mad, bloodthirsty man we talk about all too readily. He had, on the contrary, a keen intelligence, a clear reason, a great sense of self-possession. But his education as a young king, the absolute power closed to all eyes which he exercised in his royal residence, where the authority of the Queen Mothers and regents was felt only intermittently and only in the most serious cases, had developed in him defects that would have destroyed any other. He was deliberate, capricious, even whimsical.

Locked in his cold, dark palace, and, more than that, chained by the narrow rites which since time immemorial had regulated the doings of the kings of Annam and which could only be broken with poison, he was gripped by the desire for freedom that our presence helped to provoke. It was very difficult, indeed, to bend a young sovereign to the tyrannical rules from which he saw the French as being exempt, to persuade him to respect ancient practices, unpleasant to bear, when they were to us, as he knew well, a subject of mockery.

The Commander of the Royal Guard and his Escort

From there sprang the breaches that were imputed as crimes, the freedom of manners and language of which the court complained, bringing their grievances to the Résident supérieur, who sometimes had to intervene.

Added to this, at an age when most Annamites were rarely married, Thanh-Thai had a large harem of legitimate wives, concubines and servants, and this hardly helped his intellectual and moral balance. In the long hours of confinement and idleness, he indulged in brutalities, even appalling cruelties, which were too easy for us to explain, and which we exaggerated at pleasure. Readings made to him from French books, histories of the lives of our ancient kings, were not always edifying. They excited his imagination, pushing him to seek dangerous experiences.

It did not seem feasible to me that we should continue to keep this young king as tightly locked and bound by rules of another age as his predecessors had been. When everything around the royal citadel was being transformed, when a free life, the right to move, to work in a place of one’s choice, to acquire and to possess, would become the common lot of his subjects, should the King of Annam alone be cloistered, controlled, manipulated like a puppet?

The rites, some sacrosanct as they are, could surely benefit from some alterations, be softened and modernised. By using the great authority of the regents, one should reach a modus vivendi which is equally accommodating to both king and court.

For all that, the accusations against Thai-Thanh will probably never cease; but their cause would disappear, and that is essential.

While I was able to talk at length with the king during the daytime rehearsal, on the night of the festivities I had to be a discreet and silent witness to the great religious ceremony over which Thanh-Thai once more presided. Already, in the Spring of the years 1891 and 1894, he had made sacrifice to the spirits of Heaven and Earth, since in the period of trouble which followed the death of Tu-Duc in 1883, no other king had twice offered the triennial sacrifice. It was an index of the restoration of political stability in Annam, and I did not fail to point this out to my royal interlocutor that afternoon.

The Nam Giao Esplanade

I arrived around midnight at the Nam-Giao Esplanade, led by an interpreter of the palace. The silent crowd formed groups around the village altars they had brought. They could only see, of the ceremony, glimmers of smoke drifting skyward, beyond the dark area of pine wood. They only knew that in that mysterious compound, their king and his mandarins were trying their best to secure the most favourable outcome from Heaven and Earth, that is to say, giving them a reason to live and hope, that for which they prayed fervently. From this human mass, enveloped by the darkness of a moonless and starless night, arose not a cry, not a murmur. The presence of so many people created the most profound silence, heavier than if there were no-one here at all.

At a signal, the door of the enclosure opened to let us pass. We crossed the dark and empty wood where nothing sounded, nothing moved. Here and there, standing next to the trunk of a tree and merging with it, a soldier stood silent and immobile. He was not looking to see who we were; no-one who did not have the right to enter would ever dare set foot in this inviolable enclosure, no-one would ever dare commit the double crimes of lèse-majesté and lèse-divinité.

We arrived at last at the great square esplanade which represents the Earth. We climbed the stairs; the show was unexpected, unforgettable. The surrounding terrain was filled with vast altars, decorated, lit, on each of which a large buffalo, killed and skinned, spread its white flesh. A mandarin officiated at one altar with a few servants. Close by burned a large fire which, in a moment, would roast the entrails of the victims. These were the scenes of ancient Greece which we had before our eyes, as we discovered the cult of ancestor worship of the Annamites and Chinese.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.