Rails have been target and weapon since 1939

The superimposed initials on the shield-shaped Việt Nam Railways emblem are VHX. They stand for Việt Nam Hỏa Xa which, literally translated, means the “conveyance which runs by fire.” What a grand piece of oriental poetry that is, especially when applied to a rakish 4-6-2 pulling a meter-gauge express of yellow-trimmed green cars along the rugged cliffs at Cape Varella, with the South China Sea breaking on the rocks just below the wheels.

For nearly the past 30 years, however, “conveyance which runs under fire” would have been a better name, for since 1939, the Việt Nam railways have operated under the guns of war, knowing intervals of peace no longer than three years. Even now, Vietnamese trains continue to run in the vortex of the third-costliest war of this century. Instead of a pretty little express swinging along the sea, today’s train is a creeping mixed – perhaps in South Việt Nam, an American diesel hood unit pushing a flat car ahead of it to detonate pressure mines, and trailing a consist interspersed with armored cars full of troops; or in North Việt Nam, a Soviet bloc diesel feeling its way through recently repaired bomb damage. As always where rails and war mix, the railroad is both a target and a weapon, and often is the last cohesive long-distance transportation for the common people, the slender economic thread which prevents villages from reverting to medieval isolation with only a slow and unsafe highway between them.

An examination of the Việt Nam railway system logically divides into two parts: the history under French rule, when all of Indochina, including what is now North and South Việt Nam, Laos and Cambodia, were under a single political sway, and a Frenchman dreamed of linking all with a single meter-gauge rail network that would reach by interchange all the way to Singapore and maybe Burma and India; and the history of South Việt Nam’s railway in the present conflict. A fundamental political event in Southeast Asia occurred in 1954, when the Geneva agreement ended French rule of Indochina and partitioned Việt Nam at the 17th Parallel, cutting the Trans-Indochina Railway near its center and setting up South Việt Nam and its railway, the VNHX, as separate entities.

An examination of the Việt Nam railway system logically divides into two parts: the history under French rule, when all of Indochina, including what is now North and South Việt Nam, Laos and Cambodia, were under a single political sway, and a Frenchman dreamed of linking all with a single meter-gauge rail network that would reach by interchange all the way to Singapore and maybe Burma and India; and the history of South Việt Nam’s railway in the present conflict. A fundamental political event in Southeast Asia occurred in 1954, when the Geneva agreement ended French rule of Indochina and partitioned Việt Nam at the 17th Parallel, cutting the Trans-Indochina Railway near its center and setting up South Việt Nam and its railway, the VNHX, as separate entities.

To understand Việt Nam’s railway it is necessary to know some Vietnamese geography, demography and history.

The coast of Việt Nam extends for 1,200 miles along the South China Sea, from the Gulf of Tonkin to the Gulf of Siam – a shoreline comparable in length to the East Coast of the United States, although journalists tell us that this war is being fought in a “small country.” For comparison, if Boston were on Việt Nam’s China border, Hà Nội would be about at New London, Connecticut; the partition line between North and South would be at Washington, DC; Saigon would be around Waycross, Georgia; and the tip of the Cà Mau peninsula would be south of St Augustine, Florida.

Although the country has great length, it has little depth. Even its narrow shape on the map is misleading, for only the Mekong Delta in the South, the Red River Delta in the North, and the land around a series of small river mouths up in the central coast are densely settled. Here as many as 1,300 persons per square mile crowd onto 20 per cent of the land area. The 80 per cent of the country which is mountainous upland is populated at a density of as little as 5 persons per square mile, with only a few “western frontier” towns such as Đà Lạt, Buôn Ma Thuột, An Khê and Pleiku dotting the high elevations of the interior. Furthermore, the people who live in the interior are primarily primitive tribes, alien and for the most part hostile to the coastal Việts. This makes the country well adapted to the guerrillas – every populated area is immediately abutted by hundreds of square miles of wilderness, usually protected by the thick canopy of tropical rain forest where an army willing to abandon the roads can move undetected, virtually at will.

Cochinchine – A bamboo bridge

Nor is the coastal settlement a uniform strip. The population has settled at the river mouths, and between these river mouths, mountain spines projecting from the highlands down to the sea separate the settlements. There are many places on the central coast between these mountain spines which resemble the American desert, because without a river, these coastal valleys are often blocked from the rain and grow only cactus and desert brush. The railway, running the length of the coast, pierces these mountain spines and desert valleys to link the river-mouth settlements. Where through service on the railway is interrupted, the old geographical separation quickly reasserts itself, for the highway in its present condition is only a meager, primarily local substitute in civilian travel.

South Việt Nam as a separate entity is not just a political fiat of 1954, but has many historical precedents for its division, starting with the southward push of the Việts in the 10th century. Originally, the Việt people occupied only the Red River Delta around Hà Nội and Hải Phòng. Between 938 and 1400, they pushed south along the coast, driving scattered fishing tribes of apparently Polynesian origin back into the hills to become the mountain tribes of today. By 1400, the Việts had reached to where Đà Nẵng lies today, and had run up against the Kingdom of Champa, a Hindu, racially Indian culture, which they proceed to exterminate over the next 100 years. Thus, the dividing line between North and South Việt Nam now lies just about at the point where the Chinese-influenced culture of the Việts spreading South met and turned back the Indian-influenced cultures of Champa and Khmer coming east and north.

Between 1400 and 1698, the Việts drove onwards to Saigon. Not until the 18th century were the Mekong Delta and the Cà Mau peninsula settled by the Việts. The striking fact is that most of the settled land in South Việt Nam has been populated by Vietnamese for less time than the East Coast of the US has been settled by Europeans. In fact, the Vietnamese still call the territory beyond the Mekong the “New West.” In the process of southward colonization and conquest (which between 1818 and 1863 even extended the Vietnamese empire into Cambodia as far as Phnom Penh and Tonle Sap, the “Great Lake”), the southerners acquired a different dialect and a local political fealty.

Saigon – Arroyo Chinois

In a civil war that lasted from 1545 to 1777, with intermittent truces, the South under Nguyễn princes rebelled against the Lê and Trịnh princes of the North, and during this entire period the South was separately governed. In the 1630s, the Nguyễn erected two great walls across the country at Đồng Hới, a few miles from the present 17th parallel line. Not until 1802 was the nation reunited under a single ruler, and by then the concept of North and South Việt Nam as separable political entities was well established. The separation was underlined by the history of the railway, which was built in separate northern and southern sections, and not linked into one until 1936 – only to be sundered again in 1954.

The French ruled Việt Nam, Laos and Cambodia and French Indochina from 1884 until 1954. The nations within Indochina retained their separate political identity and their royal families, and the relationship of the French to the local rulers was formally different in each place. The Governor General of Indochina was appointed by Paris and he governed from Hà Nội, but Paris supplied little direction to its appointee and he ruled as he saw fit, obtaining appropriations from the French National Assembly by a series of more or less desperate appeals. Despite vitriolic propaganda to the contrary in America, this led to a benign colonialism, in which Việt Nam acquired a school system that generated one of the highest literacy rates in Asia, a strong civil-servant class which years of systematic assassination by the Communists has not wiped out, and a more diversified economy than the pre-French rice culture.

The railway and the highway system are among the best examples of the nature of colonial rule. In many colonies outside Indochina, railways were built primarily to haul a single raw material out of the interior to the coast, leading with some justification to the charge of colonial exploitation. In Việt Nam, the railway was built to serve Việt Nam, and not an external consumer of its product. Everything Việt nam exports – its peacetime rice surplus in the Mekong and Red River Deltas and its rubber, for example – moves in patterns that have little to do with the great coastal railway. That line instead distributes the country’s products internally, and carries its people between their own cities. The Việt phrase Độc lập – which means independence – is an old rallying cry under which the Việts threw off Chinese masters of the past; and it was heard again when Northerner and Southerner alike threw off the French. But this desire for national self-rule was not the result of an abusive colonial policy. It was simply the rejection of any outside domination, no matter how benign.

Cochinchine, Mỹ Tho, 1904 – Le train en gare (Fonds Breton)

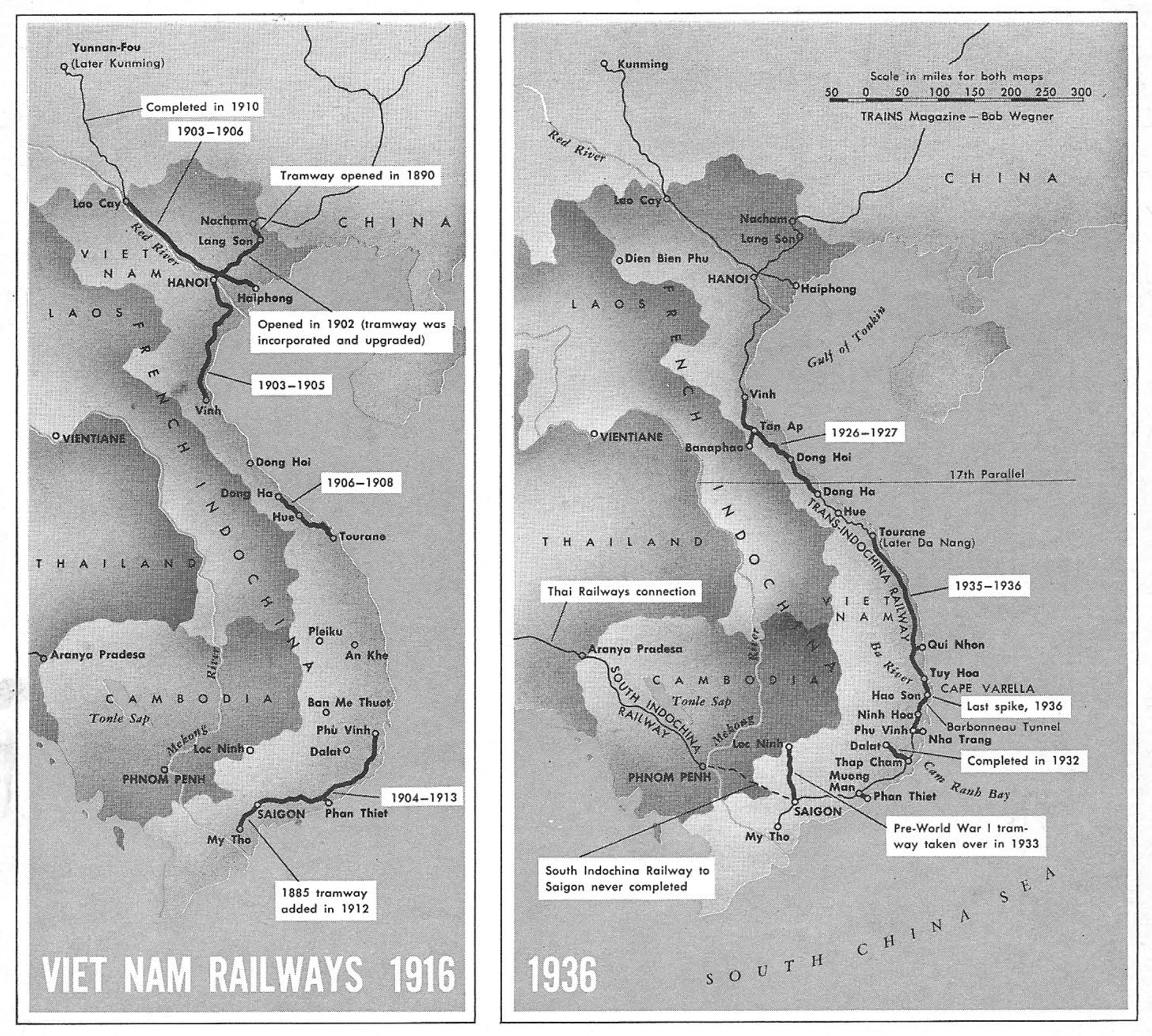

The two earliest railways in Việt Nam were tramways – a metre-gauge line from Saigon to Mỹ Tho, opened in 1885, the year after French suzerainty over Việt Nam became official; and a 60-centimetre tramway from Lạng Sơn to Na Cham along the Chinese border, opened in 1890. These lines were modest local ventures, and it wasn’t until 1902, with the start of Governor General Paul Doumer’s grand design for an Indochina railway system, that a meaningful start was made on a railway system for the country.

Doumer was the great man of France’s administration in Indochina. He presided over the colony for most of the first three decades of this century, and in that time his administration advanced most of the road, railway, school and civil-government system Việt Nam has inherited. The Doumer Bridge in Hà Nội, whose bombing made news in 1967, is named for him. His vision for an Indochina railway system involved a great coastal line from the China border through Hà Nội to Saigon, and a continuation line from Saigon to Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and on to a connection with the Thai railway system at Aranyaprathet. The Thai system – meter-gauge like Doumer’s – connected with the Malayan system, which reached all the way to Singapore and was of the same gauge as systems in Burma and India that could be reached by relatively short connecting links. The cross line from the port of Hải Phòng to Kunming (formerly Yunnan-fu), China, the capital of Yunnan province, was a contemporary but separate project, conceived in Paris as part of the establishment of French influence in Yunnan.

Two separate government corporations were set up to execute Doumer’s vision: the South Indochina Railway to build and operate the line from Saigon to the Thai border; and the Trans-Indochina Railway to take charge of the coastal line. Both companies were financed through the sale of securities in France. Frenchmen and French institutions bought colonial railway bonds as a patriotic duty – the philosophy was that the colony did not seem likely to return more than was invested in it, but was a kind of national status symbol and an obligation of la mission civilatrice, the French version of the “white man’s burden.” The Việt Nam Hỏa Xa, as successor to the Trans-Indochina company, still regards itself obligated by some of these securities, since the South’s independence from France was accomplished in the end by treaty, and not accompanied by a repudiation of debt. Although the coolness between Saigon and Charles de Gaulle’s government masks the fact, Việt Nam’s government retains strong cultural and – by its own choice – economic ties with France. However, the corporate form of the VNHX does not alter the fact that it is an arm of the South Vietnamese government, just as SNCF is an arm of the Government of France. Management responsibility, both before and since partition, is vested in a board of directors appointed by the government in power at the time.

Tonkin – Passengers board a train at Đồng Đăng

Construction began with the 1902 opening of the line from Hà Nội to Na Cham, 100.2 miles. The northern end of this road included the 1890 tramway right of way, which was upgraded and converted to meter gauge. From 1903 to 1905, the line was built south from Hà Nội to Vinh, where end of track remained until after World War I. In the South, the line was built from Saigon to Phú Vinh (a village near Nha Trang) between 1904 and 1913, and the tramway line to Mỹ Tho was purchased and added to the Trans-Indochina system in 1912. A central segment connecting Tourane (now Đà Nẵng), Huế and Đông Hà was constructed in 1906-1908. This 10 years of feverish construction gave Việt Nam about 500 miles of coastal railway by 1912. Coupled with the separate Hải Phòng-Yunnan project – the Vietnamese portion of which was completed from 1903 to 1906 – and branches, the 1916 Việt Nam railway system was 1,200 miles.

The First World War, of course, consumed the energies and talents of France from 1914 to 1919, and for a recovery period thereafter, so that major construction did not begin again until 1926-1927, when the northern and central sections were joined by construction between Đông Hà and Vinh. German reparations, in the form of both locomotives and truss bridge spans, helped in this venture. German reparations materials continued to arrive until 1933, when the Nazis came to power.

The French did not undertake to close the gap between Tourane and Phú Vinh/Nha Trang until 1935-1936. This section presented the greatest engineering obstacles, and offered the least traffic. The obstacles were all concentrated between Nha Trang and Tuy Hòa, where the mountain backbone of Việt Nam projects into the sea at Cape Varella. The peaks in this range attain heights of 6,000 to 7,000 feet – modest by the standards of the Himalaya chain with which these mountain spines eventually connect, but equal to the mountains of Montana contested by the Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and the Milwaukee, and virtually devoid of suitable railroad passes. Also, at Tuy Hòa, it is necessary to cross the broad flood plain of the Sông Ba. This difficult 70 miles was closed by means of 10 tunnels (including the 3,600-foot Barbonneau tunnel, the longest in Việt Nam), some sheer rock cuts, and a cliff-hugging shelf blasted out along the shores of Vũng Rô (Phú Yên). The Sông Ba was spanned by the longest bridge in Việt Nam, consisting of 21 197-foot spans. The official joining of the rails took place near Hảo Sơn station, just north of the Barbonneau tunnel, in 1936. The Việt Nam system thus attained a peak mileage of 2,080.

The Trans-Indochina company added to its main line and branches in 1933 by absorbing a pre-World War I tramway line running to Lộc Ninh, famous in later years as the site of a special forces camp that in January 1968 repelled Korea-style human wave attacks with point-blank artillery fire. The government wanted this line as part of an interior route through Laos, whose other end was to be the branch from Tân Ấp to the Laotian border at Banaphao. The line would have run from Banaphao across Laos to the Mekong River, then south through Laos and Cambodia to join the old tramway line at Lộc Ninh. The tramway company was the same one that ran Saigon’s now long-discontinued meter-gauge streetcars, but whether or not this line was electrified is not known. The Laos line never got any farther than its 1933 beginnings.

By far the most spectacular branch was the Đà Lạt line, which climbed 12 per cent grades with the help of three Abt rack sections to reach the resort city of Đà Lạt. The branch was begun in 1914, but the rack portion was not built until 1927-1932. This line is still operating with Swiss-built steam rack locomotives [Operation of the Đà Lạt branch was temporarily suspended in November 1968 owing to intense Việt Cộng attacks] and will be examined in detail in part 2.

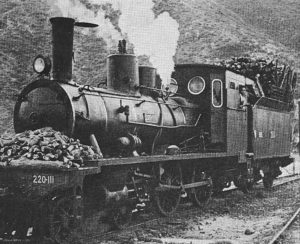

Handsome 4-4-0s, built in 1902, were Trans-Indochina’s first passenger power. With a brass-bound boiler, armor-plated cab, and 54-inch drivers, this engine performed switching in 1963. (Việt Nam Hỏa Xa)

The rail alignment passed some large towns a few miles inland in order to get a narrower crossing of rivers, resulting in short spurs to Phan Thiết, Nha Trang and Quy Nhơn.

The South Indochina Railway, the other line projected by Doumer, was constructed from Phnom Penh to the Thai border, but the Saigon-Phnom Penh link was never completed. The native hostility of the Cambodians for the Việts, who subjugated them well into the 19th century, plus the fact that the swamp-and-jungle route and a bridge over the Mekong would be expensive, probably contributed to a lack of enthusiasm for the line.

It has already been stated that the Hải Phong-Yunnan line was a separate enterprise. France had a long history of interest in Yunnan province, a remote and underdeveloped mountain region adjacent to Indochina’s north-west frontier. In 1897, France signed an agreement with China permitting France or a French company to build a railroad from the Indochina border to Kunming (Yunnan-fu). In 1903, this was refined into an agreement for the French Railroad Company of Indochina and Yunnan to build a line and operate it for 80 years, at which time China would have the option of purchasing the road for its original construction cost. The portion from Hải Phòng to the border at Lào Cai was built in 1903-1906, and the balance of the line to Yunnan-fu was finished in 1910. For many years (until the north and south sections of the coastal line were linked), this line carried a heavier traffic than the Trans-Indochina, but within China it operated only in daytime because of the depredations of a virulent form of Chinese banditry.

Standards of construction were high on the Việt Nam railways. Steel ties and deep rock ballast are the rule. The rail is 60 to 65 pounds per yard, and the axle loading over most of the system is 16 tons (US). Both of these figures are adequate for a railway of light European standards. The loading gauge, 3.9 meters high by 3.1 meters wide, is the widest of all of Asia’s meter-gauge systems. Tie spacing is 73 centimeters (about 28 inches) – close for steel ties. The coastal main line is without serious grades – climbs of 1 per cent are rare – although this was at the cost of some expensive cuts in a few places where mountain spines reach down to the coast. The Hải Phòng-Yunnan line, however, is another matter. It climbs from sea level to 6,000 feet, using several miles of sustained 2.5 per cent grades compensated by a 0.5 per cent reduction around the curves, which are as tight as 14.5 degrees. There are 115 tunnels on this line, totaling over 10.6 miles in length.

Pacifics took over as Trans-Indochina’s prime passenger power in 1930, when woodburners arrived from Germany as WW I reparations to France. Hanomag 4-6-2 “Pacific” No 231-402 (ex Cambodian Railways No 2) is shown here at Tháp Chàm in 1967, photo by Paul S Stephanus

During the brief halcyon period of the Trans-Indochina, from 1936 to 1940, it was possible to travel from Saigon to Hà Nội in meter-gauge sleeping cars. The distance was 976 miles (about the same as New York-Chicago on New York Central) and took some 48 hours (vs 16 hours between the US points at that time). Local service was provided by self-propelled gasoline railcars called automotrices, which were also popular for local services in France. The freight service on the line was light, but included movement of rice from the surplus regions at the ends of the country to the deficit regions in the center. By travelling on to the Chinese border at Na Cham, one could theoretically make a series of rail connections across China and the Trans-Siberian Railway all the way to Paris, although a ship from Hải Phòng or Saigon would probably have been faster and certainly less complicated, considering the constant upheavals in China and the stern view of foreign travel in purge-era Russia. The China connection to Kunming was a dead-end, since it did not join with the rest of China’s rails.

The year 1939 saw the start of World War II in Europe (it had begun in China in 1937), and 1940 witnessed the start of war troubles for the Việt Nam railways which have never ended. The Hải Phòng-Yunnan line was the first to feel the impact. The Chinese government undertook a program to upgrade the Chinese end of the line for both day-and night operations, envisioning supply through Hải Phòng, then a neutral port. Thus supplied, the Chinese could hold out in the Yunnan mountains against the advancing Japanese. This activity drew Japanese bombers, and in 1940 they destroyed two important bridges inside China. The damage was repaired, but the harassment by the Japanese and the unwillingness of the French company to spend money to upgrade the line prevented the Chinese from reaching their goal of 15,000 tons per month over this route. In May 1940, France was overrun by the Nazis, and in September 1940, the Vichy government accorded Japan the right to land troops in Indochina. The former route of supply became a route of menace, and the Chinese tore up a section of track near the border and blew up a bridge they had just repaired to block the Japanese advance along this route.

Vietnamese carry goods and produce aboard the mixed train two hours before departure time at the bombed-out station of Hảo Sơn. Trains on the run between Hảo Sơn, Nha Trang and Tháp Chàm were the most dependable in the country until Việt Cộng activity in 1968 slowed operations. Metal ties in gons will help repair the line to Tủy Hòa. (photo by Paul S Stephanus)

The Japanese occupation of Indochina was followed in 1942 by their sweep of the entire Malay peninsula down to Singapore. (Thailand, which allied itself with Japan, gave passage to the Japanese invaders of Malaya from Indochina). Thus, in 1942, the Trans-Indochina coastal main line found itself carrying freight for the conquering Japanese invaders of Malaya, and a record 240,000 metric tons of freight was moved vs 60,000 to 100,000 metric tons from 1923 to 1935 (before the two halves of the system were linked together). This attracted Allied air attacks, and the Trans-Indochina was cut in several places by bombing, usually at key bridges. Ironically, some of the some of the damage in 1945 was inflicted by the battleship New Jersey, which recently returned to shell the Việt Nam coast.

In 1945, the French garrisons in occupied Việt Nam revolted from Vichy and declared for the Free French. A majority of these troops were Vietnamese regulars in the French Army, and more than half were killed in a fighting retreat to Yunnan or in Japanese prison camps. Little French power or presence remained in Việt Nam or Indochina when peace came in August of that year. Vietnamese nationalists led by Hồ Chí Minh demanded that Paris grant them independence. It is probable that France would have done so, had not the French government been in such disarray at the time; as it was, the initiative was left to generals on the local scene. A series of incidents culminated on December 1946 in a coordinated terrorist attack throughout Việt Nam by Hồ Chí Minh’s guerrillas, the Việt Minh, and France was plunged into the tragic Indochina War.

The French forces on hand were so meager that they quickly lost control of the countryside and were confined to a few enclaves around cities, from which they made sporadic thrusts that ended either in “no contact” or in bloody ambushes. The railway between towns was left exposed, and it suffered many times the damage it had taken in World War II. The Việt Minh apparently assumed that their advantage in the countryside was temporary, and that France would soon be throwing against them divisions of European troops which would move along the railway. Actually, France never greatly increased the level of its military operations in Việt Nam, and even the troops and equipment she could afford to send were bitterly resented by the French population at home, who sought an end to the colonial involvement. In any case, the destruction on the railroad was nearly complete.

Annam, 31 March 1949, attack on a train at Sa Hùynh

Locomotives and cars were rolled out onto bridges, and since explosives were lacking, bridge truss, rolling stock and all were pried off the pilings and into the water with jacks. Bridge pilings were reduced with sledge hammers and hack saws, and miles of track material were torn up, carried away and buried. One hundred and ninety four railroad employees were killed and 972 were injured in war incidents from 1947 to 1954.

By the early 1950s, it was evident that the waves of French divisions were not coming. The Việt Minh were in such complete control of some areas, such as the famous “Street without joy” north of Huế, that they repented their destruction and restored service, using flimsy wooden trestles, hand pushcars, or tiny gasoline speeders, pulling handcars with temporary thatched roofs and sides. These Việt Minh trains ran on fragments of line north of Đà Nẵng until May 1955, when the Việt Minh withdrew under the Geneva Agreement.

The slaughter of the garrison at Điện Biên Phủ in 1954, and the French surrender at Geneva shortly thereafter, partitioned the country and the railway at the 17th parallel, and created South Việt Nam as a separate political entity. Đông Hà became the northernmost operating point, just as it had been “end of track” for the central section from 1908 to 1927. A total trackage of 872 miles of the old system was inherited by the South’s VNHX, of which virtually everything north of Ninh Hòa was either inoperable or could support only the section-speeder-type trains used by the Việt Minh. But peace was at hand at last, and the government in the South faced the rebuilding task ahead.

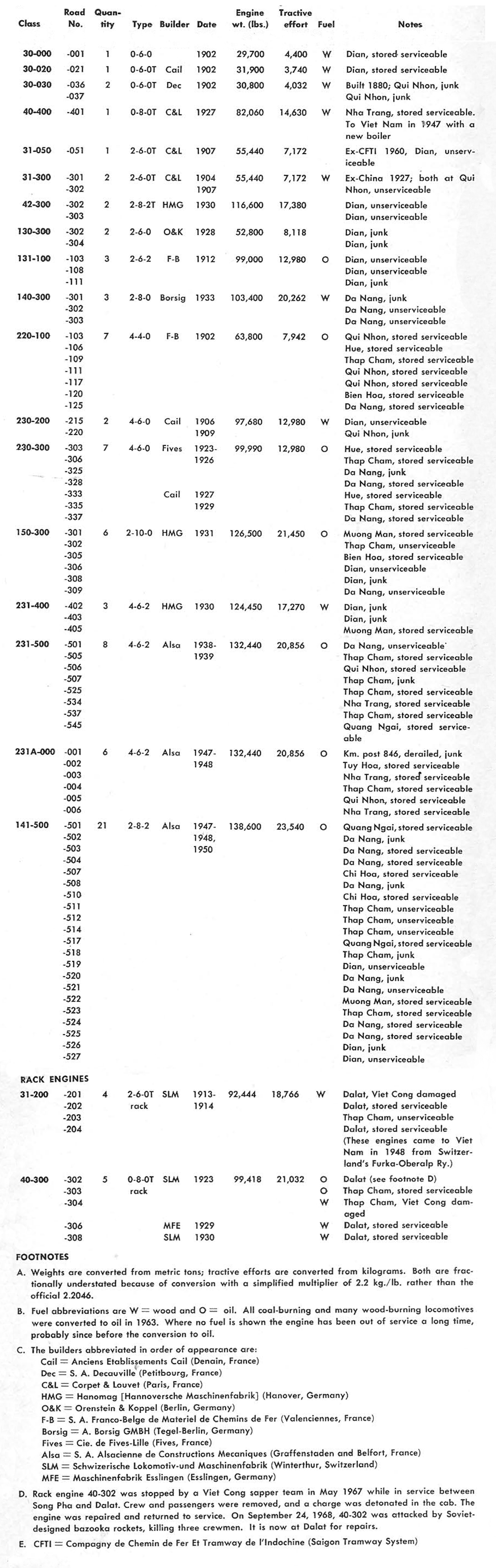

SOUTH VIỆT NAM’S STEAM POWER

This roster lists the 87 surviving steam locomotives in South Việt Nam, and gives a sample of the pre-partition Việt Nam roster. The absent numbers often belong to locomotives in North Việt Nam.

This is the first of two articles on the railways of South Việt Nam written in 1969 for Trains magazine by Jerry A Pinkepank – to read the second article, click here

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2012) and also gives talks on the history of the Vietnamese railways to visiting groups.

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group Rail Thing – Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam for more information about Việt Nam’s railway and tramway history and all the latest news from Vietnam Railways.