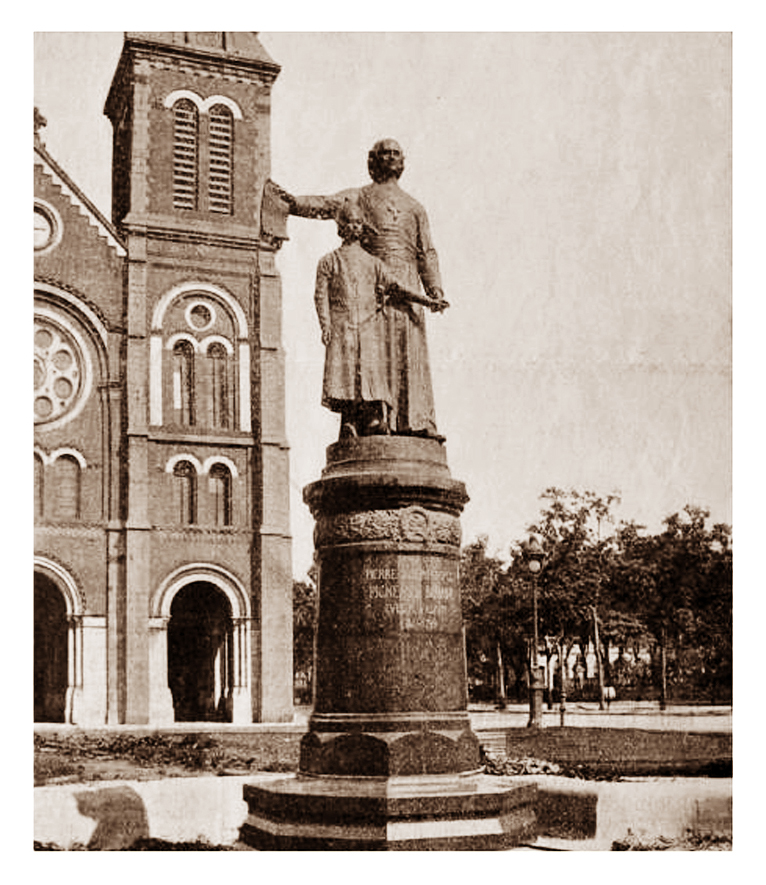

Édouard Lormier’s statue of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine and Crown Prince Cảnh pictured during the colonial era

This 1902 article from the Annales des Missions étrangères de Paris describes the inauguration of Édouard Lormier’s statue of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran and Apostolic Vicar of Cochinchina on 10 March 1902. The statue was removed during the August Revolution of 1945 and replaced in February 1959 by the present Virgin Mary statue by Italian sculptor Giuseppe Ciocchetti.

The statue of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran, Apostolic Vicar of Cochinchina in the 18th century, was recently inaugurated on the most beautiful square in Saigon, capital of our colony of Cochinchina.

Before recounting the festivities which took place on this occasion, let’s briefly summarise the career of the missionary bishop.

Pigneau de Béhaine, painted by Maupérin during his 1787 trip to Paris with Crown Prince Cảnh, on display at the Paris Foreign Missions Society

Monsignor Pierre-Joseph-Georges Pigneau de Béhaine was born on 3 November 1741 in Origny, in the département of Aisne. His studies were begun at the Collège de Laon, continued at the Séminaire de la Sainte-Famille in Paris, and completed at the Séminaire des Missions-Étrangères.

He left for the Far East in 1765. At first, he became a teacher at the Collège général, which was then based in Hon-Dat, in the Gulf of Cambodia. However, when the Siamese invaded this part of the Annamite kingdom, Monsignor Pigneau was thrown into prison, where he remained for several months. After his release, he went to Pondicherry with what remained of the college faculty, and settled in Virampatnam. In 1771, he received the papal bull nominating him as bishop of Adran. He was consecrated in Madras in 1774, and in 1776 he returned to Cochinchina, a land which was then experiencing the horrors of civil war.

The legitimate sovereign, Nguyen-Anh, better known under the name of Gia-Long, had been driven from the capital of Hue by the Tay-Son rebels. Hoping that our country would find great benefit from settling in Cochinchina, Monsignor Pigneau offered Nguyen-Anh the aid of France, which he accepted. He then came to Paris with the eldest son of the deposed king, Prince Canh, who was then aged five or six years. Thanks to his skill, a treaty was concluded between France and Cochinchina and signed on 28 November 1787, offering us many commercial benefits.

Unfortunately, the government of Louis XVI did not keep the promises it had made, and did not send to the king of Cochinchina the troops it had undertaken to provide. However, Monsignor Pigneau was not discouraged, and, with courage and perseverance, brought to Saigon two ships loaded with around 100 French officers and soldiers, as well as munitions.

Feeble as it appeared, this aid, consisting of elite men, was sufficient to ensure the victory of Nguyen-Anh and to permit him to regain the throne of his ancestors.

Seven-year-old Crown Prince Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh, painted by Maupérin during the prince’s 1787 trip to Paris with Pigneau, on display at the Paris Foreign Missions Society

The political role of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine in particular has struck the minds of the historians and colonisers of our epoque; but his religious role was no less important. Of that we can be convinced by reading the biography which one of our colleagues, M. Louvet, dedicated to the great and holy bishop, under this title: “Missionary and Patriot, Monsignor d’Adran.”

Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine died on 21 October 1799. His protégé, Gia Long, organised a splendid funeral for the man he called, out of respect, “Master.” He also delivered a great eulogy at his tomb, a translation of which we provide below, and raised a monument to him which time and persecutions have since respected.

It was in memory of this missionary bishop that, on 10 March 1902, our colony of Cochinchina inaugurated a bronze statue.

The idea of the installing a statue of Monsignor Pigneau first came to Bishop Colombert (died 31 December 1894). Sadly, his successor Monsignor Dépierre (died 17 October 1898), who followed him so quickly to the grave, did not have the joy of seeing the realisation of the vow made by his late predecessor. However, it was on his initiative that, on 28 April 1897, a meeting composed of all senior officials of the colony and presided over by M. Doumer, Governor General of Indochina, was organised to deliberate on the opportunity and convenience of raising a monument in memory of the Bishop of Adran.

This project having been adopted unanimously, the inauguration of the monument was fixed for 16 December 1899, the 100th anniversary of the great royal funeral which Gia Long (the name taken after his coronation by Nguyen-Anh) organised for the late Bishop of Adran.

A special Statue Committee was set up, and at its first meeting, an action group was formed, made up of the most honourable personalities of Saigon, and a public subscription launched to raise the necessary funds. Within very little time, fundraising was carried out throughout of all French Indochina, passing through the Court of Hue and all provinces of Annam, and eventually raising the figure of 50,000 francs, including 3,000 francs granted by the French Minister of Fine Arts, on the request of M. Le Myre de Vilers, deputy from Cochinchina.

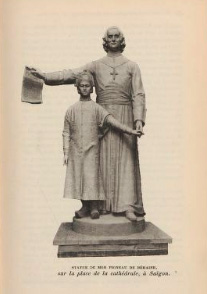

Another view of Édouard Lormier’s statue of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine and Crown Prince Cảnh pictured during the colonial era

The Saigon Municipal Council, uniting behind the movement of sympathy which flocked to the cause of our patriotic missionary bishop, authorised, by means of a resolution dated 8 January 1898, the installation of his statue in the Cathedral square.

The statue itself was commissioned from the well known sculptor, M. Édouard Lormier, and its casting was entrusted to the Maison Barbedienne, a foundry famous for this kind of work.

M. Blanchet, Director of the Compagnie des Messageries fluviales de Cochinchine and President of the Chamber of Commerce of Saigon, being in France at that time, was specially appointed by the Statue Committee, of which he was then Vice President, to confer and agree with the artist and the foundry, so that the statue might be in Saigon by 16 December 1899, the day fixed for the ceremony of its installation. However, unexpected obstacles led to delays, so that sadly the statue could not be installed at the appointed time.

It is only fair to pay a very special tribute here to the zeal of M. Blanchet, and to recognise that it was only through his goodwill, his remarkable activity and his unfailing perseverance that everything was finally ready for 10 March 1902.

On that day, in front of a large crowd which came to applaud the work realised by Monsignor d’Adran, the inauguration of the statue took place at 7am.

The statue depicts the bishop standing, larger than life (2.9m), with his right hand outstretched and holding the Treaty of Versailles (28 November 1787), which his diplomacy had secured from Louis XVI, and which assured Gia Long, Emperor of Annam, the alliance and the aid of France.

His left hand, lowered, falls gently on that of Prince Canh, his royal pupil, who, standing at his side, seems be presented by Monsignor Pigneau to the people. The plinth, made of beautiful red granite from Scotland, measures 3m in height. One detail is not without interest: M. Lormier himself made the voyage from France to Cochinchina to oversee all of the preparations, and was thus able to witness the triumph of his work.

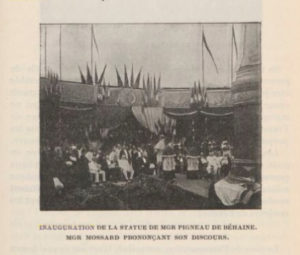

The inauguration of Édouard Lormier’s statue of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine and Crown Prince Cảnh on 10 March 1902

The Public Works Directorate made all the necessary preparations with exquisite taste. The stands allocated for guests and VIPs, along with those for the military band and the choir of the cathedral, were decorated with beautiful palm leaves, in the midst of which floated the colours of France.

The inauguration day arrived. This was one of those most beautiful days of the Far East, where the sunlight brought a special lustre, highlighting the various ornamentations of flowers and palms mingling with flags and banners.

Already by 6am, many delegations from neighbouring Annamite parishes of Saigon had arrived with their banners and taken their places around the lawn, in the middle of which stood the covered statue of the bishop of Adran. From that time onwards, the crowd increased steadily, and soon the great square of the Cathedral had an unusual animation.

A few minutes before 7am, the six bells of the beautiful church built by France sounded with great solemnity. The Church, France and Annam had come together to join in their respects and worthily honour the hero of the day, Monsignor d’Adran, who during his lifetime was able to unite the three loves to which he was dedicated: the love of the Church, of which he was the representative; the love of France, of which he was a son, and the love of Annam, of which he was a missionary and later a saviour.

At 7am precisely, the Governor General, M. Paul Doumer, arrived to preside over the ceremony. He was received by Monsignor Mossard, Monsignor Caspar (Apostolic Vicar of Northern Cochinchina based in Hue, who had come to Saigon for the occasion), M. Cuniac, Mayor, and M. Blanchet, latterly President of the Statue Committee. Then, followed by his staff and his Christian Annamite secretary, the Governor General took the seat reserved for him. At his side were Admirals Pottier and Bayle, Commanders of the French Fleet in the Far East and their staffs, military and civilian authorities of the colony, and many missionaries. The ceremony began.

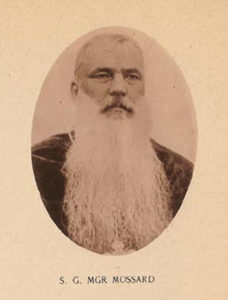

Monsignor Lucien Mossard delivers his speech at the inauguration of Édouard Lormier’s statue of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine and Crown Prince Cảnh on 10 March 1902

In an excellent speech, M. Blanchet, in the name of the Statue Committee, entrusted the monument to the city; it was accepted by the Mayor of Saigon, M. Cuniac.

After the veil which had previously covered the statue fell to the ground, M. Lormier’s work was blessed by Monsignor Mossard, clad in a cassock with capelet, waist sash and skull cap, while military music intoned a patriotic song. Thus did France salute one of its most illustrious sons.

Monsignor Mossard then addressed the meeting, arguing cogently that, in this world, it is Divine Providence which sends men out in pursuit of God’s glory.

A high Annamite dignitary, the Phu Nghiem (an Annamite title designating a great mandarin), wearing all the insignia of his rank, spoke on behalf of the Annamite people, adding his voice to that of the Bishop and the Lieutenant Governor, M. de Lamothe, in recognising the benefits brought to the country by Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine.

Finally, with the speeches at an end, a cantata composed specially for the occasion was sung by the Annamite children’s choir of the Cathedral. Their voices seemed to be voices of hope, celebrating in advance the glories and the beautiful promises for the future reserved for those Annamite people who, in greater numbers every day, have come to stand in the shadow of the Cross.

Speech by Monsignor Mossard, Apostolic Vicar of Western Cochinchina, delivered at the inauguration of the statue of Bishop Pigneau de Béhaine on 10 March 1902

Ladies and gentlemen,

Monsignor Lucien Mossard (1851-1920), Apostolic Vicar of Western Cochinchina

This monument, raised to the glory of the Bishop of Adran, and intended to perpetuate his memory in Cochinchina, illuminates with a new clarity a great truth which is all too often ignored: I refer to the intervention of Divine Providence in all things here on earth. The Pigneau de Béhaine statue, standing in the shadow of the Cathedral of Saigon, is one of the answers of Providence to three centuries of bloody persecution.

The famous “reasons of state,” so often invoked by governments of all epochs to justify their excesses, were not ignored by the emperors of Annam. Over time, ladies and gentlemen, this “reason of state,” so greatly advocated yet so little understood, and almost always misapplied when it was not an expression of morality and law, was eventually turned against those very people who had transformed it into a criminal abuse. In this way did the almighty hand of God bring the true point – the death on the Cross of Jesus Christ – into our human affairs.

And if we seek a human agent of this Divine Providence, do we not find one in the missionary bishop, to whom the Emperor Gia Long gave public testimony of civility, and whom the Prince Canh, standing next to him here, seems to present to the Annamite population as the most perfect model of a teacher and a wise, dedicated and loyal friend.

It has rightly been said that, in troubled periods of history, the challenge has been not so much doing one’s duty as knowing what that duty is. The Bishop of Adran was in Cochinchina when the revolt of the Tay-Son triumphed. Having dethroned the reigning Nguyen dynasty, the Tay-Son then threatened to extinguish its last scion, Prince Nguyen Anh, who, reduced to helplessness, found himself at the mercy of the conqueror, condemned to lead the hard life of a fugitive and outlaw. Our illustrious prelate, whose soul was kneaded with loyalty, courage and respect for established authority, espoused without hesitation his righteous, yet still unrecognised, cause.

Emperor Gia Long (1802-1820)

Not only did he save from death the heir of legitimate kings, he also helped Nguyen-Anh to recover his belief in the future of his cause, and strengthened the resolve and courage of his followers. Furthermore, he secured for his royal protégé the assistance of his homeland, our generous nation of France, which has always been willing to help others in times of misfortune. The wise approaches and prodigious activity of the Bishop, together with the valour of the French officers and soldiers he enlisted to his cause, soon changed the course of events.

The fugitive Nguyen-Anh was finally able to bring victory under his standard, and when, the uprising crushed, he ascended the throne of his forefathers, he could add a new jewel to his crown: Tonkin and Annam permanently removed from the hands of the defeated Tay Son. There we have it, ladies and gentlemen, a point of Annamite history which I hope no-one will ever contradict.

It was his selfless service rendered to their royal dynasty, his tireless dedication to the cause of their country, that so many of the Annamite literati, from Saigon to Hue, from Haiphong to Hanoi, wanted to recognise and reward. Indeed, they responded well to the call of committee for the installation of this statue. While understanding how grateful they were for the contributions made by this great bishop, we must thank them for having so spontaneously and sometimes so delicately expressed their feelings about his memory.

As for us, French outsiders who follow anxiously the progress of our national flag around the world, whose hearts leap with joy at the triumphs of France and bleed with anguish during its setbacks, we salute this man of broad and fruitful ideas who was determined that, in the Far East, the French name should be synonymous with progress, civilisation and true freedom.

We salute one whose whole life was dedicated to the service of God, Annam and France, and who died in pain, having accomplished – alas! – only a very small part of what he had intended to do for the good of all three. We welcome this statue. It will be like an open book, for future generations to read a glorious page of Gestes de Dieu par les Francs.

Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau, who served the Nguyễn dynasty

It will speak out loud, telling us that the strife and struggles of political parties, in short everything that today agitates the minds of our mother country, could not, in this colony, divide truly French hearts. Yes, ladies and gentlemen, it will say that we all stood together here, to offer this bronze statue to an illustrious compatriot, the Bishop of Adran, a long famous name, now the most honoured, the most popular in Cochinchina.

Alongside the bishop of Adran, let’s also salute with emotion and gratitude all of our other brave compatriots who supported him with courage and dignity. Let’s salute Dayot, Magon, Vannier, Girard, Guillon, Chaigneau! Let’s salute Oliver, Lebrun, Barisy, Despiaux! Let’s salute the sailors and soldiers who followed them into danger, and to glory! To them, we say: Today your names may mostly remain unknown; but this statue will remind us of your heroic phalanx. Through it, you will live again in this land of Cochinchina, in the company of the missionary bishop who you loved, and with whom you now share, I hope, endless rest.

I thank the Governor General for the kindness with which he deigned to accommodate the proposed installation of the monument proposed by my venerable predecessor in order to celebrate, as befitting, the 100th anniversary of the death of the bishop of Adran.

I thank the members of the Saigon Municipal Council for unanimously taking the decision which conceded this town square, unquestionably the most appropriate in the circumstances, for the installation of the statue. For this act of patriotism, they are entitled to our gratitude and to the recognition of the Annamite people.

I also have the duty to say a warm thank you to the committee members, department heads, officials and colons who echoed and responded to the call for subscription funding which we sent out.

Emperor Thành Thái (1889-1907) contributed a 300 piastre subvention to meet the cost of the statue’s inauguration ceremony

Let me, in closing, express my admiration and offer the homage of my recognition for the well-known artist, M. Lormier. May the great bishop, whose virtues he has revived in this bronze statue, one day give him the rewards due to those whose civic virtues have been supernaturalised by Divine Faith, Hope and Charity.

Imperial Order

On the occasion of the inauguration of the statue of Bishop of Adran, the first Mandarin of the Emperor of Annam brought to Bishop Mossard an Imperial letter, together with the sum of 300 piastres destined for the celebration of a solemn service for Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine. Here is a translation of the letter:

The 26th day of the 1st month of the 14th year of Thanh Thai (5 March 1902).

Imperial Order issued by the Secret Council (Co-Mat) of the Government of the Empire of Annam.

At the start of the establishment of our Empire, His Majesty the august Emperor and founder of our dynasty, The-To-Cao-Hoang-De (Gia Long), instructed His Lordship the Bishop of Adran, provided with the rank of Thai-Tu-Thai-Pho (Great Tutor to the Crown Prince) and the high noble title of Bi-Du Quan-Cong, to take his eldest son, the Crown Prince (Dong Cung) under his charge to France, in order to request assistance from that noble country in the form of warships and soldiers.

It was thus that His Majesty the Emperor Gia Long was able to reoccupy the capital of Phu-Xuan, and finally to secure the submission of all the countries making up the Empire of Annam.

His Lordship the noble Bishop and the Dong Cung in effect rendered important services to our dynasty. After the establishment of our Empire, We honoured the memories of all those who served in the cause of our dynasty, notably His Lordship the Bishop and the Dong Cung. Now, the Protectorate and the Mission, by mutual agreement, have installed in the province of Gia-Dinh a statue of the late Bishop and the Dong Cung, forever to bequeath their illustrious memories to posterity.

A frontal view of Édouard Lormier’s statue of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine and Crown Prince Cảnh

We are very pleased with the marks of sympathy given in this circumstance to these two illustrious personages.

We order our Imperial Treasury to send to the Mission of Saigon, via our Minister at the Mission, Nguyen Than, Kham-Mang-Dai-Than, Can-Chanh-Dien-Dai-Hoc-Si, Dien-Loc-Quan-Cong, the sum of 300 piastres for ritual or memorial services.

Let this be respected.

That is our message.

(Seal of the Co-Mat).

Speech by King Gia Long at the funeral of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine on 16 December 1799:

“I had a sage, the confidant of my most secret thoughts, who, despite the distance of thousands of miles, came into my kingdom and never left me, even when fortune eluded me.

Why must it be now, at the moment when we are the most united, that this premature and untimely death comes to separate us forever? I talk of Pierre Pigneau, Bishop of Adran, and keeping always in mind the memory of his virtues, I want to give him a new token of my gratitude. I owe it to his rare merits. If in Europe he was known as a man of superior talent, here he was regarded as the most illustrious foreigner ever to appear at the court of Cochinchina.

In my youth, I had the pleasure of meeting this precious friend, whose character fitted so well with mine. When I took my first steps towards the throne of my ancestors, I had him at my side. For me he was a rich treasure, from whom I could draw all the advice I needed to direct me.

The text of Nguyễn Phúc Ánh’s eulogy at Pigneau’s funeral on 16 December 1799

But all at once, a thousand misfortunes fell down upon the kingdom, and my feet became as shaky as those of Thieu-Khang dynasty of the Ha, so that we had to take a path that separated us as far as heaven from earth. But you, dear Master, you embraced our cause with a firm and faithful hand, following the example of four old Hao sages who reinstated the Crown Prince of the Emperor Han-Cao-Te to his rightful status! I confided to you our Crown Prince, when you accepted the mission to go and seek on my behalf the interest of the great monarch who reigned in your country. And you managed to get help for me.

They were already at the half way point when your projects encountered obstacles that prevented them from succeeding. Despite this, you wanted to return to my side, regarding my enemies as yours, to seek the opportunity and the means to combat them. In 1788, when my flag was once more raised over Saigon, I looked forward with impatience to some happy noise announcing your return from France. And in 1790, your boat came floating back onto the waters of Cochinchina. In the skilful and full way of gentleness with which you trained and led the Prince, my son, we saw that heaven had singularly gifted you with the skills of education and youth leadership.

My esteem and affection for you grew day by day. In difficult times, you provided us the means that only you could find. The wisdom of your advice and virtue that shone into the playfulness of your conversation brought us closer and closer, we were such friends and so familiar together that when business called me out of my palace, our horses walked side by side. We never had anything but the same heart.

Another colonial-era view of Édouard Lormier’s statue of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine and Crown Prince Cảnh

Since the day when, by happy chance, we met, nothing could alter our friendship, our mutual dedication and boundless confidence that marked our relationship. I hoped that robust health would enable me to continue tasting the sweet fruits of such unity for a long time! But now the dust covers this beautiful tree! What bitter regrets!

To show everyone the great merits of this illustrious foreigner and spread abroad the fragrance of the virtues he always hid under his modesty, I deliver to him the title of Tutor of the Crown Prince, confer on him the dignity and title Quan Công and give him the name Trung Ý. Alas! When the body dies and the soul rises towards the sky, who could keep it chained here? I have finished this short elegy, but my regrets will never end. Oh, beautiful soul of the Master! Receive this homage!”

For Pétrus Ký’s detailed description of Pigneau’s funeral, see Pétrus Ký – Historical Memories of Saigon and its Environs, 1885, Part 1

For more information on Pigneau’s tomb, see Lăng Cha Cả – From Mausoleum…. To Roundabout!

Édouard Lormier’s 1902 statue of Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine and Crown Prince Cảnh pictured during the colonial era and Italian sculptor Giuseppe Ciocchetti’s 1959 Virgin Mary statue pictured today, from the Facebook group page “Saïgon Chợ Lớn Then & Now”

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.