Emperor Bảo Đại (1925-1945) pictured during his voyage home in 1932 (Mondiale Photo-Presse)

The young emperor Bao-Daï of Annam will soon return to his country, which he aims to modernise.

He began by attending classes at a Parisian lycée, then he continued to receive lessons at home while, along with other young men of his age, he was initiated into the beauties of constitutional law and political economy at the School of Political Science.

Crown Prince Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh Thụy (later Bảo Đại) attending Khải Định’s 40th birthday celebrations in 1924 (BAVH, 1925, 2)

Yet instead of arming himself with an imperial and arrogant demeanour, this young student made himself perfectly at ease with his comrades, joking with them and permitting some to become, perhaps, a little too familiar, by cavalierly slapping the young sovereign on the shoulder, in sharp contrast with Marshal Lyautey’s respectful bows at Vincennes.

H. M. Bao-Daï lives in a luxurious residence built especially for him in the avenue de Lamballe. This is where I met him. He lives there with his tutor, the worthy M. Charles, former Resident in Annam, to whom the late emperor himself entrusted the education of the little prince.

He’s a strong young man, sportsmanlike, with a direct manner. He speaks without an accent, in very pure French. He has been conquered by the most modern ideas.

It’s no surprise, therefore, to learn that this young man has taken ardently to the joys of riding. He loves horses and is considered by the military school an excellent rider.

Tennis is also a sport he is keen on. He handles the ball skillfully, and his elegance and flexibility are renowned on the courts, where he plays with his friends, and with young women and young girls carefully handpicked by Mme. Charles.

Intellectual and artistic recreations are not neglected. The emperor is not a very fervent reader of books, but he loves shows, and especially musical performances. It’s quite curious that this young Oriental delights above all in musical concerts, particularly the classics. He never tires of Bach or Beethoven, for example.

Although very musical, he is not, however, a skilled musician. He plays a little piano, but does not claim to virtuosity.

In short, despite the courses he was obliged to follow, he has had a happy time during the 10 years he has spent in Paris. So we may understand the regrets that the little king does not hide when leaving France.

Emperor Bảo Đại during his enthronement on 8 January 1926 (BAVH, 1931, 1)

“I so love your country,” he has said, “to which I owe my intellectual formation. And how could I forget the kindness of all my friends?”

We know that H. M. Bao-Daï would have liked to prolong his one-year stay in Paris. But sovereigns have duties to which they are bound even more rigorously than the common man.

Everything in Annam is now ready for the emperor’s return, and he cannot shirk his obligations. In his homeland, big things are expected from the return of the monarch. Most serious spirits have high hopes for this young emperor, whose mind has received a western education and is open to modern ideas.

“However,” explains M. Charles, “No-one among his subjects could reproach him for having broken with the traditions of his race. I have been very careful not to tear him from his roots. I wanted him constantly to remain connected to his country. He’s had with him an old Annamite teacher, a scholar of the old school, who has taught him Annamite and instructed him in the difficult knowledge of Chinese characters, the ‘Latin’ of the Annamites.”

Thus, the young emperor is completely ready to reign. It’s not with a light heart that he embarks for Annam, because he knows that his days of recklessness, car rides with classmates, cavalcades, and ardent mornings at concerts are now at an end, but he leaves France with full awareness of the serious responsibilities which will weigh upon his shoulders.

They will indeed be heavy, but H. M. Bao Daï is still young. He longs to do good for his country and, as it is so very closely tied to France, there is hope that he will lead Annam in a sincere spirit of Franco-Annamite collaboration.

Bảo Đại’s cousin Prince Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh Cẩn was sent with him to France to be educated in 1922 under the tutelage former Resident Superior and Honorary Governor General of the Colonies Jean Charles (Fonds Sogny-Marien)

He will find a friend and valuable guide in the person of the Resident-Superior in Annam, M. Yves Châtel, who, in agreement with the Governor General, has been conducting a discreet and enthusiastic publicity campaign simultaneously across the country, in favour of the young sovereign.

Itinerant singing troupes have been travelling everywhere, stopping on the banks of rivers, on the corners of crowded streets, in remote villages in the middle of rice fields. Accompanied by the high toned monochord, and in their nasal voices, they have eulogised the young king and the benefits he is expected to bring to the whole country. Justice will be simplified, the mandarins will no longer prevaricate, education programmes will be redesigned.

The youthful radiance of the emperor will add a little joy to the splendid palaces where he will now spend the rest of his days. The Imperial Palace, a succession of luxurious buildings buried in gardens and parks where rock gardens alternate with flowering lotus ponds, shelters behind a triple ring of walls in the middle of the famous Citadel of Hue, surrounded by moats and canals full of still water.

There exists in the last park a modern looking building which contrasts strongly with all the other palaces with fretted roofs. This building, built specifically to plans by the Emperor Khai-Dinh, late father of the current ruler, is called Kien-Trung Palace. It’s here that H. M. Bao-Daï, when he has had his fill of ceremonies and rites, will come to relax and steep himself in a European setting.

Recently he has commissioned from two decorators a suite of ultramodern furniture for the two rooms destined for his personal use. He intends to install a radio set and to there to receive his closest friends, including his cousin Prince Vinh, who was raised with him in Paris. He will also entertain there the many young Annamites with whom he studied, as well as high-ranking officials such as the Minister of Finance, H. E. Tai-Van-Toan, who came to visit him in France and whose lively and curious mind has also assimilated the most modern innovations. This youngest of mandarins subscribes to our greatest literary magazines; he is very interested in the contemporary intellectual movement and he will certainly be a most faithful and agreeable companion to his young sovereign.

Soon after his return, Bảo Đại embarked upon a tour of all the provinces his realm. He’s seen here visiting a royal tomb in Chiêm Son (Quảng Nam) in 1933 (Fonds Sogny-Marien)

The young emperor, who lived among us for 10 years and became used to the pleasures of Parisian life, will certainly need to escape the heavy yoke of ancestral influences and come to relax at times in an atmosphere which will remind him of the banks of the Seine. Dressed in a well-cut dinner jacket, he will drink a glass of champagne while listening to the latest fashionable songs on his gramophone. But that will not stop him, moments later, from putting on his heavy gold silk robe and receiving in his great audience hall the high and mighty mandarins, who respectfully bow before the “Son of Heaven, Father and Mother of his subjects.”

It will surely be the great merit of H. M. Bao Dai’s reign to reconcile harmoniously modern ideas with respect for the past.

The tasks with which he is encumbered will be difficult, but on the shoulders of this young athlete, the responsibilities of state will be executed with ease.

A 1930 view of the facade of the Kiến Trung Pavilion, rebuilt in east-west fusion style by Khải Định in 1921-1923 and destroyed in early 1947 (Fonds Morin-Edmond)

Another 1930 view of the facade of the lost Kiến Trung Pavilion (Fonds Morin-Edmond)

A 1930 view of a side entrance to the lost Kiến Trung Pavilion (Fonds Morin-Edmond)

The antichamber of the lost Kiến Trung Pavilion in 1928 (Fonds Sallet)

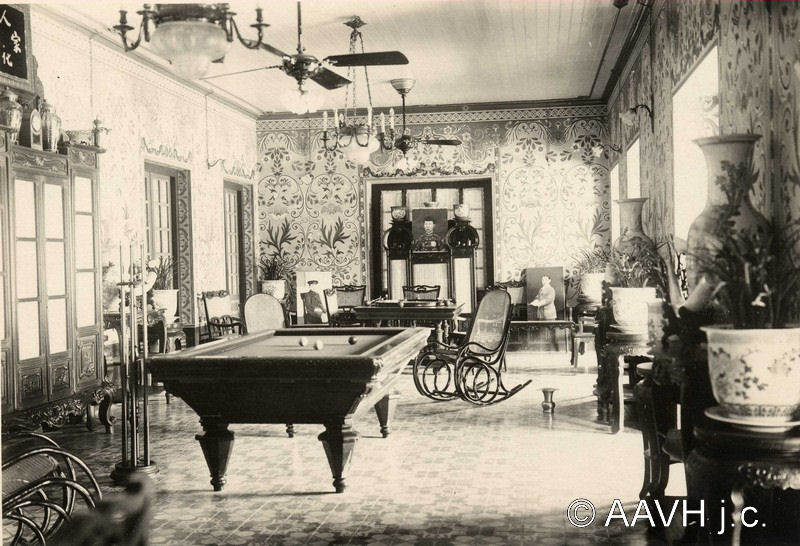

The billard room of the lost Kiến Trung Pavilion in 1928 (Fonds Sallet)

The salon of the lost Kiến Trung Pavilion in 1928 (Fonds Sallet)

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.