From our special correspondent in Tourane

It is not yet possible to measure in an accurate way the political consequences which may be forthcoming for the kingdom of Annam, as well as for our protectorate, following the sudden death of King Dong-Khanh. This death, which occurred like a bolt of lightning at the very hour that this king had raised our finest hopes for his reign, could and will probably prompt a thousand guesses. Yet before recent events are transformed by legend, it’s good to establish, according to certain testimonies, how things actually happened.

Emperor Đồng Khánh (1885-1888)

For seven or eight days, the young ruler had complained of headaches, and at the same time had given clear signs of irritability of mood. He ate little and slept badly, and his sleep was punctuated by nightmares and also, it is said, by hallucinations, which greatly concerned the court.

Then the fever took him. He was unable to attend the sacrificial ceremony in memory of Ming-Mang, then he ceased all royal audiences and could not leave his residence. Local doctors vainly exhausted him with their complicated therapeutic techniques. Irritated, he dismissed them harshly, punishing them by having them locked up and declaring that he was prepared to accept the advice of a French doctor. The Resident Superior, who had just returned home from a trip to Tonkin to be informed in Tourane, by news reports, of the progress of the illness, had called Dr. Cotte, Senior Medical Officer of the Navy, and went with him at night to the palace. The patient’s bed had been placed in one of its remotest and most mysterious rooms. Only after following, by torchlight for nearly half an hour, a series of long meandering wooden corridors and galleries, were the two visitors, accompanied by the royal interpreter, finally able to reach the patient. Only a few maids and eunuchs were watching over him in that gloomy bedroom, with its high walls of dark wood, where many candles were barely enough to give even a little light. The king was lying on a very low wooden bed, encrusted with mother of pearl. His head rested on a long hard pillow made from bamboo filaments, like those seen on all Annamite beds.

The king was wrapped in a large blanket made from yellow silk. He was already very weak, and when his two visitors were announced, he could barely lift his head. Muttering in a low voice, he thanked them for their visit and asked that they should heal him quickly so that he could as soon as possible attend to “affairs of state.” The doctor examined him with great care, and, without hesitation, said that the external symptoms suggested a pernicious fever. He did not hide from the Resident Superior the seriousness of the situation, above all if the hiccups, which had already been convulsing the patient’s body for many hours, continued to worsen, and the quinine did not work a miracle.

Dr. Cotte made up various potions, carefully prescribing the exact dosage, and left the palace after giving precise instructions to those who looked after the patient, etiquette and rites strictly forbidding a European from remaining overnight in the royal bedchamber. That night was relatively calm, but the patient was unable to keep down the potions that were administered to him.

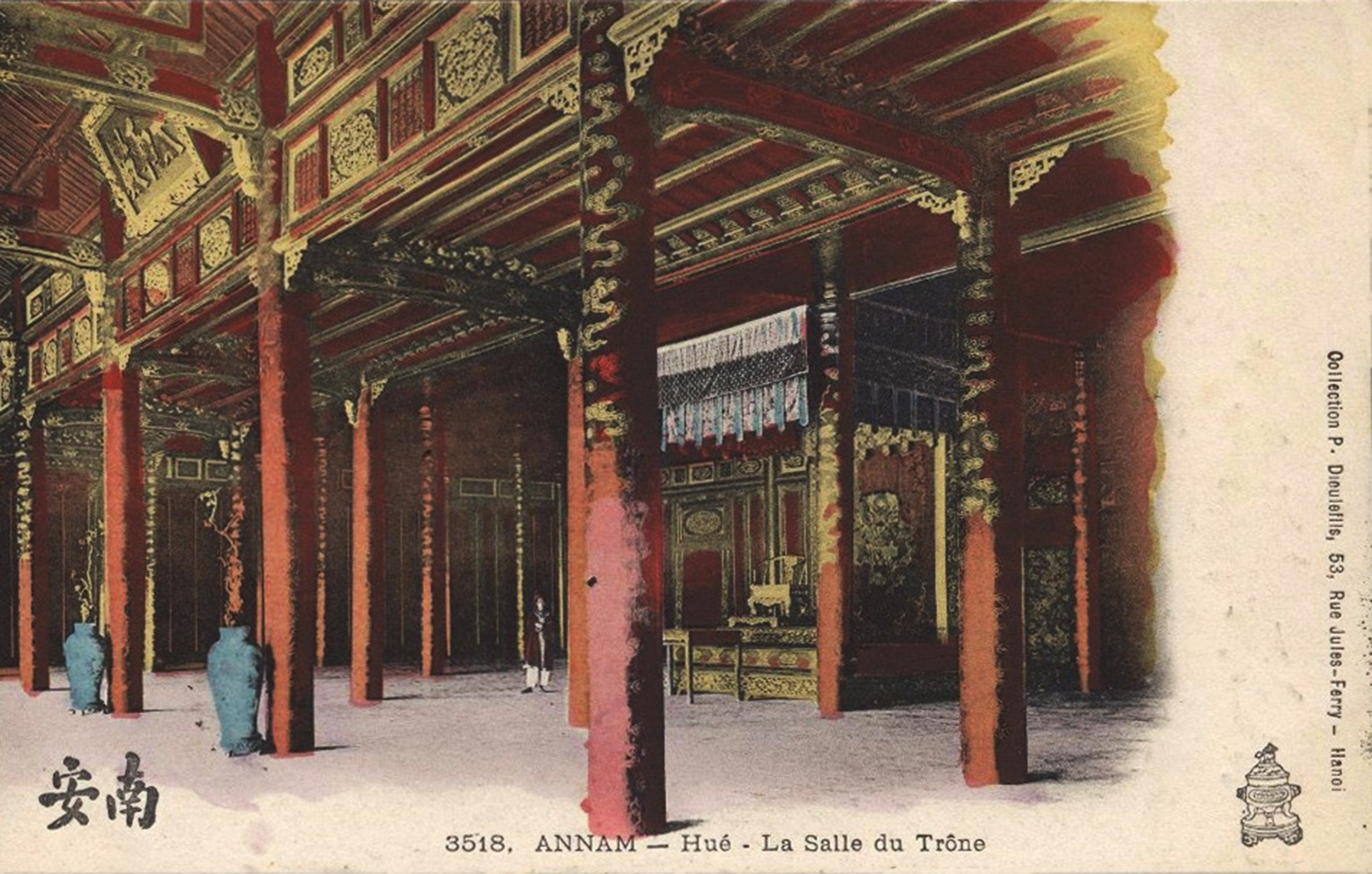

The former Cần Chánh Palace (destroyed in 1947)

Towards morning, when the French doctor returned, His Majesty asked how long it would be before he could get up, and whether he might be allowed to consume something other than the remedies. The good doctor naturally objected to the idea of the king leaving his sickbed, because his weakness was extreme, but said that he could take, if it were possible, a little sweetened milk. Soon, however, the hiccups resumed with renewed intensity. Towards evening on 28 January, the Resident Superior was warned that the king’s condition had worsened severely, and that the presence of the doctor was once again required urgently.

The Resident Superior, accompanied by his Chief of Staff, M. Boulloche, and a Navy physician named Dr. Barrat, immediately made his way to the palace. As they neared the first guard post, an interpreter ran towards them and exclaimed: “The king is dead.” Dong-Khanh had indeed passed away peacefully, without agony or external appearance of suffering. It was 10 minutes past eight in the evening.

The Resident Superior naturally judged the utility of confirming the death himself, so he was introduced once again into the king’s bedchamber. There an old priestess was reciting prayers, and fled at his approach. The high yellow drapes on the bed had been closed, so a kneeling eunuch pulled them aside. The king’s face was covered by a red silk scarf. The doctor felt his pulse and confirmed that he was dead. After bowing respectfully, the two visitors withdrew immediately.

All around, and in the adjacent guardrooms, mandarins and princes gathered, speaking in low voices, their eyes wet with tears. Yet in the royal courts of the Far East, pain, even when it is sincere, is always expressed cautiously. Regrets for a late Majesty are seen as an insult to the new Majesty who will soon be enthroned. Hardly had the eyelids of the young king been closed to the light, than it was already fashionable to discover in him terrible flaws, to recall his vices, his excesses, his brutality. In this country, as in any other, meanness, just like honour, has its propriety, and men of quality are not lacking in it.

The young Emperor Thành Thái (1889-1907) with siblings, from Quelques notes sur l’Annam, 1895

The question of the succession to the throne occupied everyone’s thoughts. This catastrophe, which had occurred so fast, took everyone by surprise and confounded all calculations. Dong-Khanh had two sons, but they were aged just four and three years, leaving the frightening prospect of a long Regency with the door left wide open to all eventualities. In any case, the Queen Mother, who in accordance with ancient rites had been consulted about the succession, had discounted the offspring of Dong Khanh from the outset.

It was anticipated that the Resident Superior, M. Rheinart, who, thanks to his long experience, knew this country perfectly, would manoeuvre with dexterity in the midst of these unknown dynastic complications.

Yet time was pressing. The throne must not be left vacant. No doubt, power was exercised in the interim by the Co-Mat, but that power was without prestige, directionless and unable to resist unforeseen adventures. In addition, never had the death of a king taken place at a more inappropriate political time. This was the eve of Tet, that most important political-religious event of the year, when superstitions ran free, when happy or unhappy omens were seen to presage future events. Already, the popular spirit, quick to judgment and influenced by ancient legends, was inclined to see in the timing of this death a solemn manifestation of the wrath of heaven against the French and all those who owed their power to us.

The Annamite people, accustomed to the long reigns of Ming-Mang, Tu-Duc and many other former kings, could not without irony notice how fragile and short were the royalties we pretended to create with our own hands, how quickly and finally the stigma of foreign investiture had killed these men. Superstition in these countries may be either the most powerful ally or the most terrible enemy. On this Tet festival, an annual celebration for which people’s expectations were always raised, everything brought discontent. An edict of the Queen Mother forbade any celebration. Thirty Chinese who had attempted, despite the prohibition, to explode some firecrackers in a suburb of Hué, were arrested, imprisoned and placed in the cangue by the Phu-Dien (prefect of police).

Among a people so fond of gaiety and laughter, everything suddenly went silent. Without doubt they had planned come out, at the time of Tet, wearing their fine new clothes, silk dresses, turbans with a thousand clever folds, but then suddenly their world became slow and without noise.

A court mandarin

Not a cry was heard, and even those who have regularly accused the Annamites of dark designs could see how quickly a people deeply ingrained with the monarchical education could became docile and ready to bow with propriety under the affliction of official mourning.

The Resident Superior, after many talks and numerous eliminations, eventually selected a son of Duc-Duc, that king who had reigned just a few days and whom the court had left to die of hunger after France had protested his elevation to the throne and declared his enthronement void on the grounds that it had been conducted without consultation. The child in question was 10 years old. The choice that we made of him also had the advantage of restoring the direct lineage of the Nguyen. Since the death of his father, he had lived in captivity with his mother and a brother, in an isolated dwelling within the walls of the Citadel. The choice proposed by the representative of France was confirmed quickly by the Council of the Court and the Co-Mat.

Envoys presented themselves at his residence and, addressing his mother, asked her to fetch her eldest son. “Here he is,” she said. “What do you want with him?” “It is he,” they answered, “who will become king of Annam.” Then she burst into tears and refused to permit them to take her child, begging that they spare him such a frightening prospect. Yet heaven had spoken and must be obeyed, so the child was taken the same evening to the palace and placed, until the time of his coronation, in an apartment not far from the royal audience hall. “Where am I, where am I being taken?” he asked the royal interpreter. “Highness, you are in the library of the kings, a library which will soon be yours.” “Good,” replied the prince, “then please give me the Analects by Confucius.” This request had much meaning, for in fact this 10-year-old child is already a scholar, fashioned by an excellent teacher. He can read and write Chinese characters and even knows the French alphabet.

He is relatively tall for his age and well built. However, his demeanour is less attractive and less aristocratic than that of Dong-Khanh, with a flatter nose, a darker complexion and a rougher skin. He has an intelligent and attentive look, but none of the rather feminine softness which accompanied the smile of the late sovereign.

When the choice of the court had been made, and on the directions of the protectorate had been officially approved by the French government, the Resident Superior, accompanied by M. Boulloche, his Chief of Staff, and M. Baille, Resident in Hué, returned to the palace to inform the future king of the decision and to present him with their compliments. By a bizarre coincidence, this was the first day of Tet. They found the child standing in a palace hung with blue drapes, surrounded by servants and mandarins.

Resident Superior Pierre Rheinart (BAVH, 12, 1943)

When the Resident Superior had been announced, the young king came out to meet him in the small courtyard in front of the palace. He was dressed in a long blue robe with stiff pleats, and wore on his head a black turban. A eunuch protected his face from the rays of the sun with a large parasol. He shook hands with the Resident Superior and his two companions, and gestured solemnly to them to sit around a table on which tea had been served. The interview was short, we understand, and limited to simple compliments. The young future sovereign then led his visitors out of the palace, sheltered as before under his parasol and walking with an already slow and regal gait.

Before paying this visit, the Resident Superior and the officials he brought with him had gone to pay their final respects to the body of Dong-Khanh. That same morning, immediately after the king’s body had been enbalmed, it had been placed in an open coffin on a funeral bier covered in precious fabrics. The body was dressed in ceremonial robes adorned with much jewelry, including diamonds and a large golden pendant inlaid with emerald dragons, which he had worn around his neck just before he died. On his head was a large ceremonial helmet, from the top of which brilliant pearls and sapphires hung on long gold threads.

The coffin itself, made from teak, was large but quite simple. Dong-Khanh, feeling full of life and hardly expecting to die so early, had not thought to have a special one made in advance, in observance of the customs and ordinary precautions of his predecessors and even of many of the rich people of this country. The coffin rested on a makeshift catafalque, draped with yellow silk and supported by two simple trestles.

The late king was laid in the royal audience hall, on the exact spot where he had once sat on his red and yellow velvet-covered throne, receiving visitors and graciously offering them tea. The courtyard in front of this hall, paved with slabs of green stone, was lined with parasols, each guarded by a eunuch. Inside the hall, lit by countless candles, were several large Buddha shrines loaded with offerings and flowers, plus objects used in the daily life of the late king which since his death had become sacred. Fragrant joss sticks smouldered slowly on the altars, filling the air with their fragrance.

The Thái Hòa Palace

After entering this hall, the visitors remained for just a few seconds, bowing in front of the remains of the prince who had so greatly loved France, and then walking out again silently.

The mandarins and the courtiers stood at the sides of the hall, just a few metres away from the coffin. At that moment, with the sun setting beyond the horizon and the silhouettes of the great Citadel gates highlighted against the clear background of a Far East twilight, the distant sound of the drums of the palace guards announced the first watch. Thus ended a momentous day of melancholic grandeur.

The former king will be buried in the same magnificent tomb he was constructing for his father, on the banks of the river and where, in recent times, he had rested so often to view one of the most beautiful mountain landscapes. The actual burial will take place on 20 February. Starting on 16 February, the court will wear the costume of official mourning, which, as we know, is white.

The royal astrologers having, after careful consideration, declared 1 February as a most auspicious day, the enthronement was promptly fixed for that date.

On the previous day, according to rites, the young prince had made his lais to his royal ancestors in the Can-Chanh Palace and received the royal regalia. He should also have received the jade family seal known as the Ngoc-Bi, but this had been taken out of the palace by Ham Nghi during his flight and lost in the mountains of Quang-Binh.

The prince was presented with the ivory plaque of the “royal order,” which served as his laisser-passer to access the Gold Book in the Can-Chanh Palace. This Gold Book, which is opened only at the start or finish of each reign, is presented to every future sovereign. The character written in it denoting his rank of succession will be his own name. That of the new king is Chiêu, meaning “light of wisdom.”

A mandarin dispensing justice

The mandarins attached to the Noï-Cat (Cabinet of the King) then select a number of literary expressions formed from two characters with the most favourable meanings in the eyes of Heaven. The list of such characters is then offered to the new king, who chooses from it his regnal name. That name is then transcribed in the Gold Book and displayed in all the temples of the ancient kings and in the Nam Giao (Temple of Heaven). The new King of Annam will be called Thanh-Thai, which means “absolute happiness and success in all things.”

The coronation ceremony was held with great pomp and ceremony. Against custom, French troops had penetrated through the gate and were lined up alongside the terrace leading to the Thai-Hoa Palace. Since the new king was about to receive the investiture of France, it was appropriate that our troops came, as had happened during the coronation of Dong-Khanh, to give character and meaning to the ceremony through their presence in the interior palace.

With the Commander of the Brigade, the Head of Cabinet, M. Boulloche and the Resident, M. Baille by his side, the Resident Superior advanced into the royal audience hall. All the officers who were not under arms stood in a group some distance away.

Soon, the cries of the Thi-vié heralded the approach of the sovereign. He entered slowly through a rear door behind the throne. This time, he was dressed in a royal robe decorated in gold brocade and laden with precious stones, the weight of which, although he was supported by the chief eunuch, weighed singularly on his child’s frame. He greeted the Resident Superior and his three companions, and then, not without some difficulty, ascended the steps to the throne. French batteries fired a 21-gun salute, bugles sounded in the fields and troops presented arms. The Resident Superior stepped forward, and, on behalf of the Government of the French Republic, recognised him and saluted him as King of Annam.

The emperor is carried in procession from the Đại Cung Môn to the Thái Hòa Palace

His Majesty Thanh-Thai responded in a few words, expressing his gratitude and his deep attachment to France. He read a speech which was inscribed in Chinese characters on the ivory plaque which he held in front of him, and his small but unwavering and assured voice was very well heard throughout the large colonnaded hall. As he spoke, the Thi-vié waved long fans all around him. At the foot of the throne, the perfumed smoke of an immense joss stick floated slowly towards him. The royal tablets which would be presented to him were placed on a table, locked in a gold box. After the exchange of official compliments, the Resident Superior saluted the king and moved to the right side of the room. The Annamite ceremony began.

Princes in their grand costumes, spread out around the sides of the room, now stepped forward and, standing around 15m in front of the throne, did their lais. Most were old, bent and broken by age. Five times they prostrated themselves on their knees, face against the ground, their white beards sweeping the stone slabs of the audience room. Then, royal government ministers moved forward and executed the same genuflections with similar majesty.

The great exterior courtyard was by this time filled with the busy ranks of the mandarins. On the right were massed the mandarins of higher rank, on the left those of lower rank. Groups were formed according to order of precedence, from the highest to the lowest officials of the court, and everyone was dressed in grand ceremonial costume. At a signal given by the Minister of Rites, the long lines of mandarins turned simultaneously to face the audience hall, where the child-idol sat on his throne in hieratic immobility, his feet perched on two great gold dragons.

Then there arose in the distance a bizarre and prolonged type of guttural chant, which seemed to end almost as an echo of itself. This was the signal for the huge assembled crowd of mandarins slowly to prostrate themselves, lowering their faces against earth so that they just touched the paving stones. Long robes in a thousand colours bent and collapsed, flooding the ground with their folds. The chanting continued. When it ceased, this sea of people, motionless and calm for a moment, stirred once more and rose to their feet.

Mandarins on the terrace of the Thái Hòa Palace

Then it began again. This was repeated five times, with that strange and disturbing song accompanying the lais. Each one lasts less than four minutes, and it was clear that this tough exercise was quite hard work for more than a few old mandarins. Sweating profusely in the burning sun, the courtiers continued to bend down, stand up and bend down again in silent adoration, commanded by the sacred rhythm.

I can’t think of any larger and more imposing spectacle, nor of any better staged piece of theatre to help us understand the monarchical principle in the East, and to what extent it dominates the lives of the people.

During the interval between the lais, the Minister of the Interior, Bui-Di, advanced alone towards the throne. Kneeling, he offered the new king the tribute of members of the royal family and subjects of the kingdom of Annam.

The speech ended like this: “Today, His Majesty Dong-Khanh went to join the hosts in Heaven. Already his chariot and his retinue have reached the homeland in the clouds, and we would seek in vain to keep him here. But the throne can stay empty no longer. Our late king leaves only children of young age, who are unable to sustain the great edifice of the kingdom. We are sure, sire, that we honour the noble soul of His Majesty Tu-Duc in making you the successor of Dong Khanh. We have the consent of Her Majesty the Queen Mother and of France to place you on this noble and majestic throne. We swear to be solemnly faithful and to give you our absolute dedication, proclaiming you as our master and working together to consolidate this great edifice raised by the Nguyen.” This speech was written on a register of gold so that it could be preserved in the archives of the kingdom.

Other minor officials attached to the various offices of the palace were also admitted to present their lais, and then, after the ceremony had finished, the young king was placed on a special throne of yellow velvet and carried out of the hall by six Thi-vié, who finally installed him in his apartment inside the palace.

The Queen Mother leaves her palace

We recall that on the following day, when he was presented with a report on which he had to place a little red sign as a mark of his approval, the young king hesitated for some time before taking the brush and asking what it was. It was explained to him that this was a measure prepared by the Council of the Royal Family and the Co-Mat, which required nothing more than his sanction. He asked: “So, I will also be responsible for it?” Then, seizing the brush, he signed his name in red.

Those who surround him closely know well that, barely a month before his elevation to the throne, still guarded within his prison walls, this boy collected wood each day for the fire on which his mother cooked her meagre cuisine. They describe him as an energetic, very intelligent child, who displays maturity and even perhaps a precocious mistrust. When he was first brought to the palace to await his coronation, he was served with tea. Silently, he looked at the teacup without picking it up. A mandarin, understanding the hidden meaning of his hesitation, took the first sip. Only then did the boy himself take the cup and drink the tea. Since poison and other attacks have decimated his family, it is hardly surprising that the poor child continues to be stricken with suspicion of all those around him.

A Regency Council was organised immediately under the supervision of the Resident Superior. It consists firstly of Prince Haï-Duc, President of the Council of the Royal Family and one of the sons of Ming Mang; secondly of Nguyen-Tran-Hiep, former Kinh-Luoc of Tonkin and lately Minister of the Interior, a big man, very intelligent and well educated, who has been made Commandeur de la Légion d’honneur by France; and thirdly of Truong-Dang-Quang, son of the highest dignitary of the empire under Tu-Duc and currently Phu-Dien in Hué.

The young king’s tutor will be Nguyen-Thuat, former Minister of the Interior, and currently Tong-Doc of Thanh-Hoa, one of the most open-minded and gifted men in the kingdom and, moreover, one of the friendliest to France, being one of the closest in spirit to the French by virtue of his character and natural gifts. The new charge with which he has been invested has a first-rate importance.

The royal interpreter Cilong, who was educated at the Lycée d’Alger and has received a Bachelier ès sciences from one of our universties, will continue to guide the sovereign in the study of the French language. The Court and the Co-Mat appear very satisfied with the composition of the Council of Regency, and it is certain that, given the nature of the men within our political influence, they cannot but consolidate and make progress.

A later image of Emperor Thành Thái (1889-1907)

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.