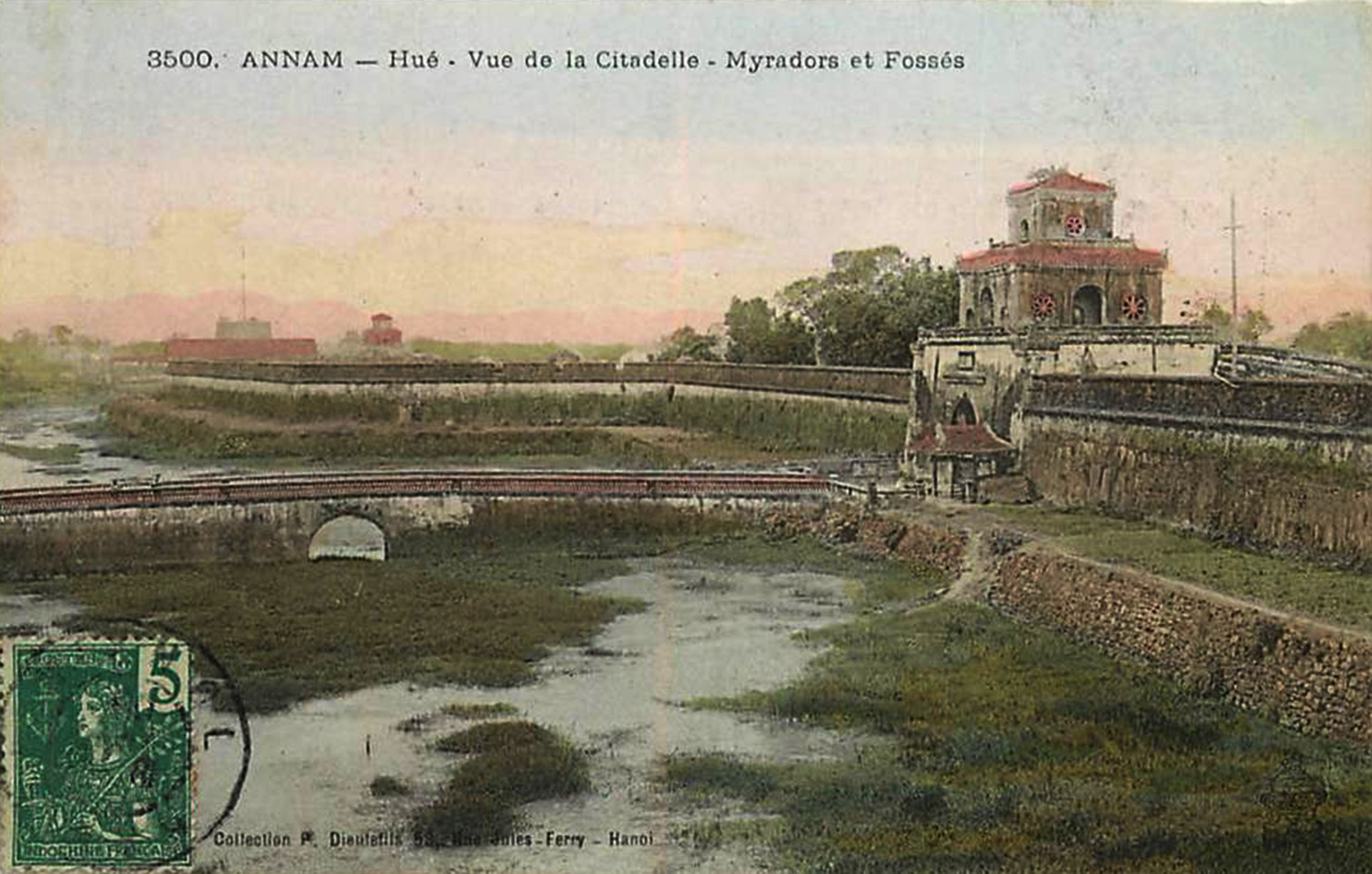

The royal citadel in Huế in the early 1900s

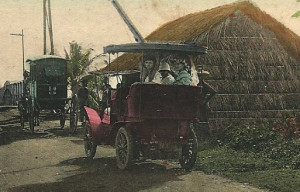

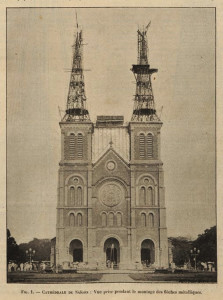

Published in l’Eveil économique de l’Indochine on 12 December 1931, “Tourism in Indochina” describes the attractions which awaited the adventurous colonial traveller 84 years ago in Việt Nam, Cambodia and Laos

Indochina certainly ranks among the leading countries in the world for “grand tourisme.” Above all, it boasts that curiosity of the first order, Angkor. That fact alone warrants much greater organisation to facilitate the realisation of private tourism initiatives in this still undeveloped land.

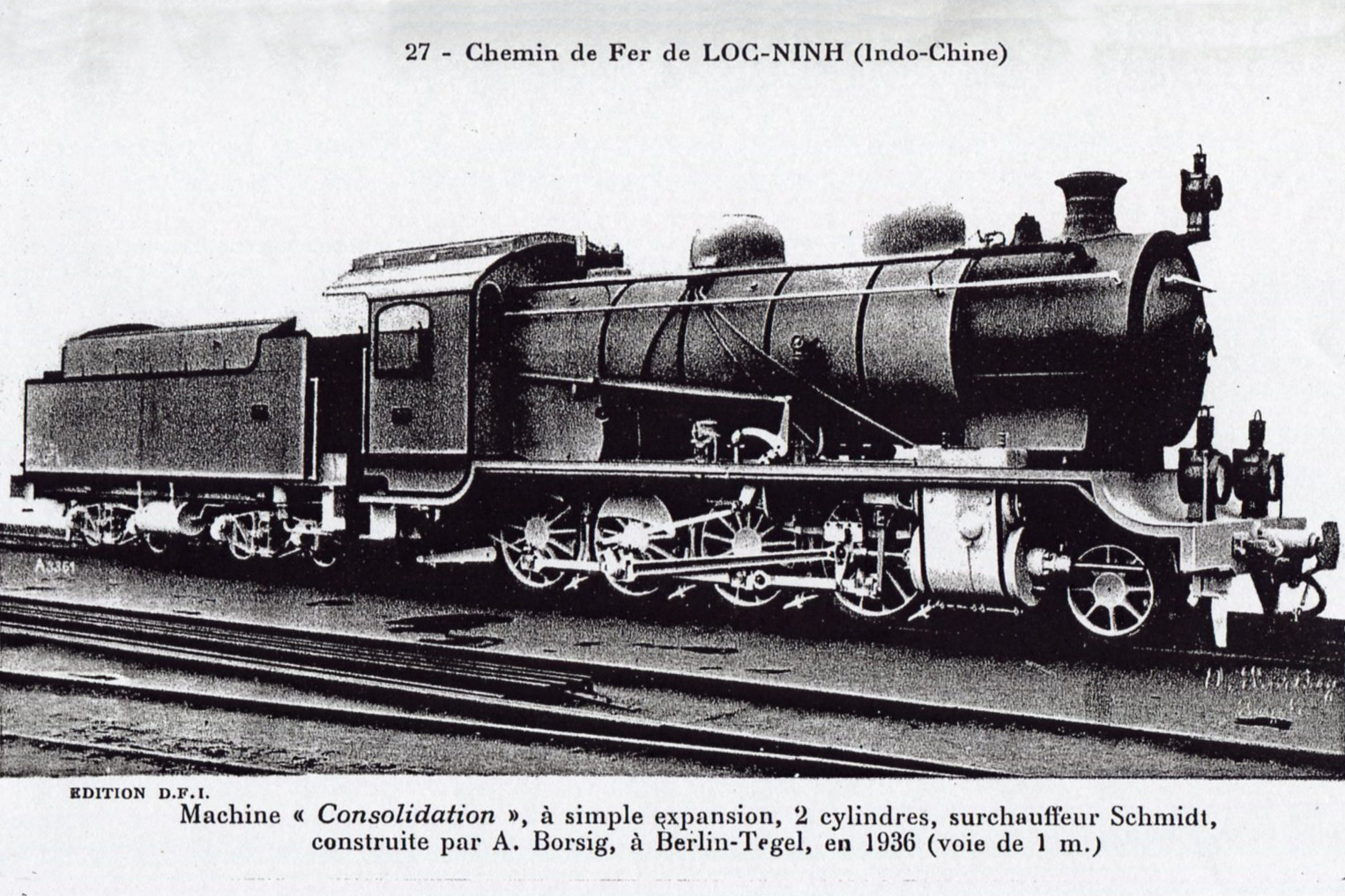

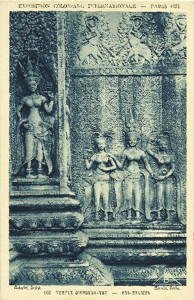

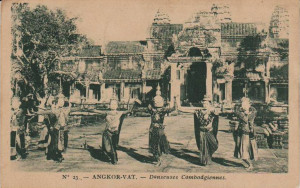

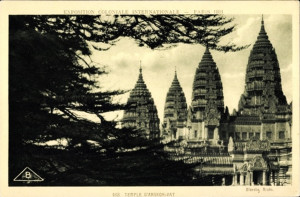

Angkor Wat, photograph from the Colonial exposition Paris, 1931

But we might jeopardise the success of the “Wonder of the World” if we place it on the same level as other tourist attractions, which at present are insufficient by themselves to attract the distant visitor. Hue and its royal tombs, big game hunting and Halong Bay are all second-class attractions which at the present time draw tourists only from Indochina and neighbouring countries, but on the other hand these places could attract visitors from Hong Kong, Singapore and Batavia who have already paid the fare to come to the Far East. Finally, there are many regional tourism attractions, interesting for locals and for foreign tourists who wish to know Indochina as a whole: for example, the Babé lakes, Khone waterfalls, Luang Prabang, Dalat, Chapa, Tourane, the Black River, etc.

The domain of tourism also comprises attractions which interest not just the colonial settler but also the affluent local population, not to mention the travel services which may be requested by those whose profession requires them to move to and reside in undeveloped regions, in localities which are currently too poor to accommodate the tourist.

It’s thus that, centuries ago, the Thai countries created the sala, a house which is made available to travellers at any significant location, or at various points along main roads, with the proviso that one must provide one’s own food and bedding. This institution is especially well developed in Siam. Although it’s very modest, the introduction of the sala in the Annamite lands would constitute appreciable progress.

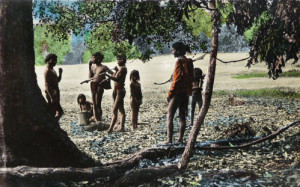

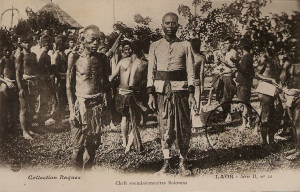

The people of the Bolovens plateau, Laos, in the colonial era

In fact, it might have been more appropriate for the authorities to start by upgrading that which already existed – to pave the mule tracks, add box culverts, pavements and roadside cafes – before undertaking costly projects like the construction of new roads. Similarly, they ought perhaps to have installed basic lodgings (salas or guest houses), before building luxury hotels, to have opened up the country using modest resources before investing millions to create high-altitude health spas.

But in this life of ours, events never follow a logical order: the war suddenly posed problems for the creators of the hill stations, and in the post-war period, which everyone had predicted would be a time of fabulous wealth, and which for a while led to abnormally high rice, tin and rubber prices, expectations became excessive. In order to take advantage of the economic boom which seemed to be enriching Hong Kong, Manila, Java and Singapore, we devoted considerable sums to the construction of luxury hotels.

Events once again dashed the expectations of those who had failed to learn from experience. The lean years showed up again suddenly, when we were least expecting them.

These days in Indochina, we rarely see the princes and billionaires on whose hospitality so much money was spent, while the prospector, the industrialist and the local official still experience the greatest difficulties when travelling in regions whose development is nevertheless desirable.

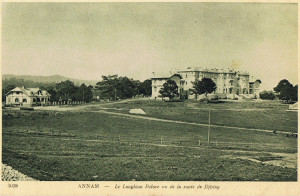

Dalat – the Grand Hotel in 1931

The crisis of 1930-1931 was a reminder to humanity of the old Bible story of the “seven fat cows and seven lean cows” of Egypt. The normal state of affairs is not that of yesterday before the crisis, it is that of today, with its hard labour law and the impoverishment of so many millionaires. And now, tourism in Indochina, which had been geared too much towards the latter, must turn towards a more modest, but perhaps more interesting customer. However much they scale down their operations, it will be a very long hard road for many of the large luxury hotels, until a new generation has become wealthy and more adequate means of transport and communication make it possible for those on more modest budgets to access our distant lands. But eventually these means will be created, the amenities procured and the burden alleviated.

Indochina, with its two ports of Saigon and Haiphong, is out of the way of most foreign ships, but many of them graze the coast of Annam without stopping, due to the lack of a port. The administration is currently considering two draft projects: one, in Nha-Trang, will require 40 million francs and several years of construction to develop a port of call, while the other, in Cam-Ranh, will cost just one twentieth of that amount and will involve only a few months of construction. The latter project would seem to be the obvious choice; it should be easy to implement and its completion will remove a major obstacle to what is known as “le grand tourisme.”

Phnom Penh Railway Station in 1933

A second obstacle will disappear when the railway connects Saigon with Phnom Penh, Battambang and the Siamese border, because not everyone shares the snobbery of those who believe themselves to be “dishonoured” when they travel by rail, indeed, many travellers prefer the comfort and convenience of the express train. When Angkor, Phnom Penh and Saigon are eventually connected by that great railway line which already links those two major ports of call, Penang and Cam-Ranh, we will multiply the number of our visitors. Already, thanks to the Siamese railway network, Angkor profits in large measure from the huge numbers of tourists attracted by our Siamese neighbours to Bangkok. With twelve or thirteen thousand visitors, instead of just twelve or thirteen hundred, Indochina will be able to start recovering some of the costs it has incurred in attracting them.

In the meantime, it would seem wise to concern ourselves mainly with local tourism, to make new efforts to attract a larger number of people to our high altitude health spas. And really, was it not for all French people, large or small, and especially children, that these health spas were built? Already, a happy change has occurred in Dalat; the original idea of setting up a “Far Eastern Monaco” has been abandoned; a second class hotel and two high schools have been built, instead of casinos, theatres and dance halls, and when the railway reaches the city, it will lower considerably the cost of living there. Several thousand French women and children will benefit directly from this tremendous effort, which we hope will also help to attract foreign visitors. They are now as penniless in Singapore as we are in Saigon, and many are eager to visit, once Dalat is cheaper to access and stay in.

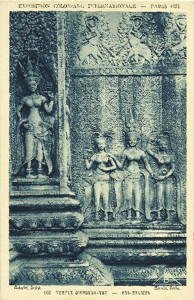

Bas-reliefs on the temples of Angkor

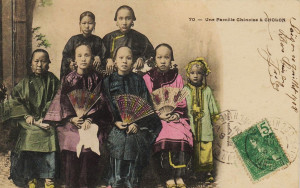

Finally, we should also think about the local people, who, as they develop and prosper, will acquire a taste for travel and will be encouraged by the new facilities.

The richest and most advanced of them will benefit greatly from the development of tourism facilities which were created for the French, in contrast to other colonies where racial prejudice prohibits the natives from enjoying such benefits. As for the less wealthy, and those who value their customs, they will be accommodated in guest houses in holiday resorts and particularly in the spas that one can already envisage developing in a country so rich in thermal springs.

If we have not yet done anything to develop tourism, it is because we never envisaged or planned for an indigenous clientele (they have long been steadfast in their disdain for the way we live) and because up to now the French clientele has always been insufficient.

If an effort is made in the popular sense that we have indicated, and above all in the development of tourism for local people, profit may accrue to those Europeans who need it.

In the light of these observations in relation to future development, we will now explain the interest which Indochina presents today, from the point of view of tourism and the resources it offers both to colonial settlers and foreign visitors.

As we have said, Indochina presents a wonder of the first magnitude, worthy of inclusion among the “Seven Wonders of the World” and comparable in beauty and curiosity to the most famous monuments, from the pyramids of Egypt and the ruins of Palmyra, Athens, Rome and Constantinople, to the most beautiful castles of the Rhine Valley and the most elegant cathedrals of France or England.

Angkor Wat, photograph from the colonial exposition, Paris of 1931

We’re talking, of course, about Angkor, for Angkor represents the best of what Indochina has to offer; none of the other sites, monuments and places of interest in Indochina are as valuable in terms of “grand tourisme” as Angkor.

So up to now it has been on Angkor that the administration’s tourism development efforts have focused: clearing the ruins (which was needed first), improving access roads, and building new hotels.

We must thank the Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) for their formidable efforts in bringing to life this “sleeping beauty.” They have freed many of the ruins from the deadly embrace of trees and creepers, and carried out extensive restoration works. Virgin forest next to the ruins has been transformed into a park, and a network of approximately 40km of fine roads now permits traffic circulation with the minimum of time and effort.

Parallel to this physical clearance and restoration work, the scientists and architects of the EFEO have undertaken detailed research into the historical, archaeological, architectural, demographic, epigraphic and artistic questions posed by Angkor. The published works of all kinds which have been borne of this research already form an extensive bibliography, while many of the statues found scattered around the various ruins have enriched the collections of numerous museums, in Angkor and Phnom Penh and, to a lesser extent, in Saigon, Hanoi and Paris.

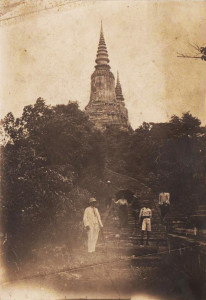

French archaeologists of the EFEO at Bakheng temple near Siem-Reap

Since the start of the French clearance and restoration work in 1907, access to the ruins has been relatively easy during the high water season, via the Great Lake, the Siem Reap river and by steamship between Saigon, Phnom Penh and Siem Reap. This is an agreeable but very slow journey whose great fault is to be seasonal and also to be possible only from Saigon, a port which was not visited by foreign passenger ships.

For several years, Angkor has been connected with Phnom Penh by means of a good road of 320km, and with Saigon via another good road of 247km. The traveller has the choice between cheap and comfortable public bus services, car rental and even a seaplane service.

At the same time, there has been concern, both in Phnom Penh and Bangkok, to connect Angkor with the Siamese capital, which is so frequented by tourists. Cambodia has built a port at Réam [Sihanoukville] on the Gulf of Siam, and a Siamese company now runs a comfortable small steamer service between Bangkok and Réam.

Finally, things are beginning to move in the right direction. For some time now, the Siamese railway has connected Bangkok with Aranya on the Cambodian border. A new road of 150km is about to open between Siem Reap and Aranya, which will reduce the overall journey time from Bangkok to 12 hours. It’s therefore probable that in future, Angkor will continue to receive the largest number of tourists via Bangkok, comprising travellers coming by rail from Penang or Singapore, and, in a few years, Rangoon and Mandalay.

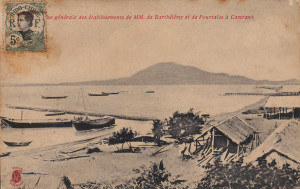

Cam-Ranh Bay

But Saigon should not lose out, because tourists don’t like to retrace their steps, and when the new Cam-Ranh port of call is realised (it will take just six months and $200,000), it is envisaged that English, Japanese, Italian, Dutch, American and other ships will willingly sacrifice three or four hours in their schedules to call in at Cam-Ranh and pick up/set down travellers coming from or going to Penang. From that time onwards, attractions of the second order will acquire a new interest and importance for “grand tourisme” – for example Phnom Penh, Saigon, Dalat, the hunting grounds of Kompong Thom and Lagna, and other attractions located on the route between Angkor, Saigon and Cam-Ranh, which will be visited in many possible variants within a period of eight days, a fortnight or three weeks, depending on the arrangements.

ANGKOR — We will not describe Angkor here. The abundant and diverse promotional material, and in particular the recent Vincennes Exhibition, have already made the ruins famous throughout the entire world, and there is surely not one large hotel, travel agency, consulate, or ocean liner that doesn’t have at least some literature on the subject.

Suffice it to say that travellers can now find there all the amenities they need: a comfortable hotel close to the ruins, and a modern luxury hotel in Siem Reap, just ten minutes away by automobile. The perfect tourist itinerary permits the visitor to vary his excursions at his discretion, placing at his disposal the most diverse forms of transportation, ranging from car to elephant and ox-cart.

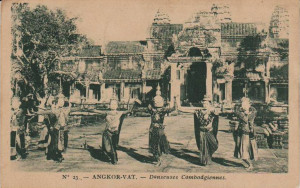

Royal Cambodian dancers at Angkor Wat

Here, the visitor will find many distractions, from those beloved of every tourist to those which are special to Angkor: for example, the Angkor Wat illuminations, Cambodian court dance performances, and visits to ruins which have not yet fully emerged from the forest. Finally, one may buy, at prices which can be found nowhere else, all of those souvenirs which are so dear to the traveller.

KOMPONG THOM — Phnom Penh is 320km from Angkor, and the journey takes between six and eight hours by automobile; but the traveller who is not in a hurry can extend his journey over two days by spending the night in Kompong Thom (167km from Phnom Penh and 153km from Angkor), where there is a hotel with 10 rooms. This permits either the organisation of a hunt, or a visit to various interesting ruins, in particular a selection of old Khmer roads and bridges and imposing monuments such as the Roluos, 16km from Siem Reap, or Kompong-Kedey (bungalow) 61km from Siem Reap.

From Kompong Thom, travellers may also visit the ruins of Sambor (32 km). Finally, not far from Kompong Luong ferry, on the Ton-Le-Sap (32km From Phnom Penh), may be found the few remains of the ancient capital of Oudong.

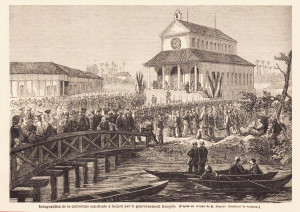

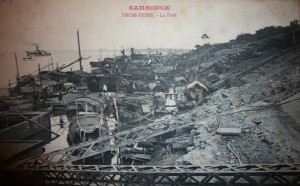

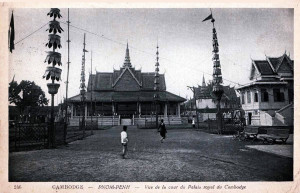

PHNOM-PENH — Phnom Penh is a major touristic centre. This is the first major city encountered by the traveller coming from Bangkok via Réam.

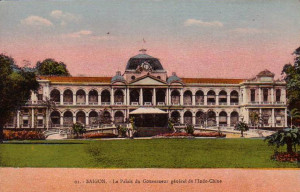

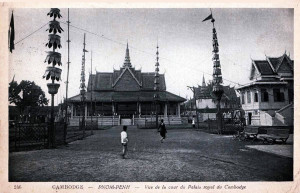

Phnom Penh – view of the Royal Palace

The city has two hotels, including a “palace” newly-built by the administration, and automobile and boat services connecting with all major centres in Cambodia, especially Battambang, Kampot and Réam. There are also connecting services to Saigon (automobile and boat) and Laos (boat only).

The capital of Cambodia, with its population of 90,000, it is a very active commercial centre. The tourist may visit the Royal Palace with its throne room, ceremonial hall and silver chapel; and the Khmer Museum, beautifully built, rich in its collections and very active as an art school. The latter also sells objects of the best artistic taste, such as mouldings and beautiful fabrics.

The city, with its bustling quays, its beautiful park surrounding various ancient and modern monuments, and native districts, is extremely interesting in itself.

Phnom Penh is the point of departure for the boats which go upstream to the Khone waterfalls and Laos, and, in the high water season, to Siem Reap and Battambang. They also depart at all times of year for Saigon and Mytho. The railway will connect Phnom Penh with Battambang in early 1933.

In the area around the city one can visit Oudong, which was capital of Cambodia several times between 1618 and 1866 and features monasteries and royal tombs.

Oudong – the tomb of King Norodom, 1914

Unhurried travelers, and those arriving or departing via Réam, will, in the vicinity of Kampot, be able to go for a swim in the sea at Kep (bungalow), or to sample the fresh air at Mount Bockor (comfortable hotel), situated at an elevation of 1,010m above sea level on a picturesque plateau.

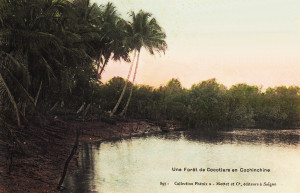

The excursion to the Khone waterfalls is made entirely by boat at the time of high water (60 hours on the ascent, 20 hours on the descent.) The falls at this time offer little of interest; however, the route through the flooded forest makes for an impressive sight.

In the dry season, it is possible to travel by automobile to Khong (Laos), either from Siem Reap via Prakan (ruins) and Rovieng, or from Phnom Penh via Kompong Thom.

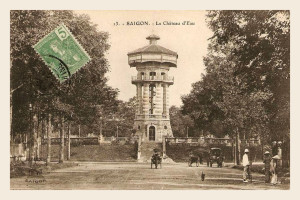

SAIGON — It is via Saigon that most tourists come to Indochina on our French ships, since the latter do not call at Penang.

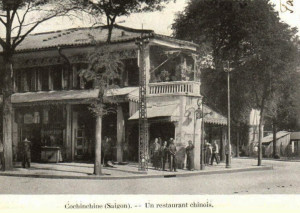

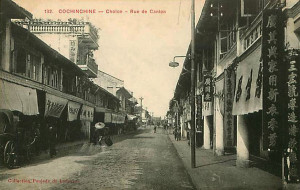

When in future the pilgrims from Angkor make their way to Cam-Ranh to rejoin their ships, most will want to stop for at least one day in the city which everyone proclaims as the most charming of the Far East, with the French gaiety of its café terraces, the Chinese gaiety of its suburb of Cholon, the splendid botanical and zoological gardens, a young museum, delightful surroundings, and many comfortable hotels.

From Saigon, as in Kompong-Thom and Vinh (Annam), one can organise excellent hunting parties. However, this attraction, which imprudent propagandists have often placed at the forefront of their tourism promotion efforts, could easily cause disappointment to dedicated hunters coming exclusively for this purpose from France or America. Indochina is only a middle-rate hunting destination. Certainly, in several places one may find elephant and aurochs [wild cattle], but there is only a thousandth of a chance of seeing a rhinoceros.

A dead tiger by Raymond Chagneau

In fact, unless you have many months to spare, the hunting here is only an attraction of the second order. But in the absence of big game, the hunter, thus warned, is guaranteed some beautiful tableaux featuring less sensational game such as deer, roe deer, agouti, crocodile, peacock, marabou stork, partridge and wild rooster, and even on occasions a tiger, a bear or a panther.

The large rubber plantations north of Saigon offer a most interesting destination to those who have never seen an institution of this kind, and experts may also be interested to visit them for comparison purposes. Visits to rubber plantations also offer an opportunity to make contact with the ethnic tribes, for those whose tourist intineraries do not offer the chance to visit the central highlands.

CAM-RANH — Cam-Ranh is a future port of call so indispensable from the point of view of the postal service as well as for tourism that there is a very good chance that the new project there will be realised; we therefore include it here. It will be of special benefit by cutting in two the trip from Hong Kong to Singapore (a route on which at present the ships are rarely full), thereby placing our high altitude resort of Dalat at the disposal of Europeans from these two major ports.

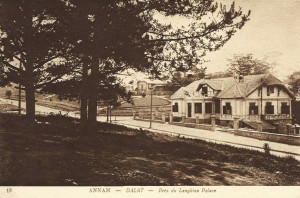

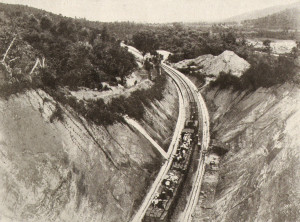

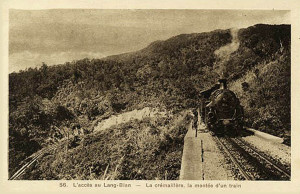

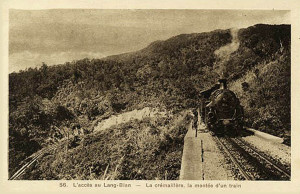

DALAT — In the meantime, two routes are available to the visitor to travel from Saigon to Dalat: the road via Phan Thiet and Djiring [Di Linh, Lâm Ðồng], 370km long and quite hilly; and the railway via Phan Rang (333km.) and the Langbiang branch, 87km long, partly a rack-and pinion railway and very picturesque.

The Langbian cog railway, opened in 1933

A good road runs besides the railway and offers travellers coming from the north and central Annam the opportunity to travel by automobile, stopping on the way (if one is a traveller worthy of the name) to visit a beautiful plantation and agave orchard on the plain and a tea plantation on the plateau.

A new road cutting the distance from Saigon to Dalat to only 322 km will open in 1932. It will connect with the old road to Djiring, where there is a hotel and it’s possible to visit several interesting waterfalls in the area.

Dalat has little other interest for the “grand tourist” than the opportunity to rest in a cool, comfortable and pleasant environment. On the other hand, for the French of Indochina and probably in future for many English people from Hong Kong and Singapore who will use Cam-Ranh as a port of call, Dalat has considerable interest as a mountain resort.

Taking as a model the famous hill station of Baguio in the Philippines (which is reminiscent of Dalat in respect of both landscape and climate), the French authorities have expended considerable effort in developing the Langbiang plateau as the summer capital and garrison town of Indochina. Already there are three hotels in Dalat, one a “palace” and the two others providing comfort for a less affluent clientele. There are also large and small high schools, a hospital with a European pavillion and many residential villas. In the vicinity, several agricultural and forestry enterprises have begun to transform Dalat into a centre of colonisation, while local tourists find it a beautiful excursion destination.

Nha Trang – the Cham temples of Thap-Ba

NHA-TRANG — The tourist who travels north, yet has no time to visit the Langbiang plateau, can go directly from Phan-Thiet to Nha-Trang via Phan-Rang, passing the famous Cam-Ranh Bay which stretches for about 20kms.

Nha-Trang, located 409kms from Saigon, is a provincial town in the gulf of the same name. It has a rather nice beach and also boasts the Po-Nagar Cham ruins, but what makes it especially interesting are the facilities of the Pasteur-Institut (both the institute itself and its plantation) and the Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries. Visitors will find two good European hotels in the town.

NHA-TRANG TO TOURANE — The journey of around 540km between the two ports can currently be made by automobile and the entire journey is extremely pleasant, thanks to the beauty and variety of the landscape. The route heads through Ninh-Hoa (60km from Nha-Trang) where the Darlac-Kontum road leads off to the northwest, then it passes the bay of Port Dayot and makes a very scenic crossing of the Cap Varella, followed by the small delta of Tuy Hoa (hotel), which has recently been equipped with an irrigation network. The crossing of the province of Phu-Yen is very agreeable, especially as the road passes the beautiful bay of Song-Cau (bungalow) and the Cu-Mong lagoon. Beyond the Cu-Mong pass, one arrives at the two chief towns of the rich province of Binh-Dinh. The native chief town has a citadel, and is the starting point of a direct route towards Kontum. Qui-Nhon, the European capital and principal port of the entire region, also has several Cham ruins. There the visitor will find a large, modern European hotel.

Qui-Nhon 1896 – Cham tower viewed from the north by André Salles

Nha-Trang is 322km from Tourane and Qui-Nhon is 240km from Tourane. On this section, one encounters the ruins of the Cham citadel of Chabari, the pretty coconut trees of Tam-Quan, the salt pans of Sa-Huynh, the capital of the province of Quang Ngai with its comfortable hotel, and, a little before Tourane, the ruins of the ancient Cham city of Singhapoura (Tra-Kieu).

TOURANE — Located in a large and picturesque bay where passenger ships call on their way to Tonkin, Tourane is an important touristic centre where one can usefully stop over for two or three days. Here one may find a big European hotel and a large, well equipped garage. Taking excursions from Tourane to the surrounding area, tourists can visit the caves and pagodas of the Marble Mountains; the ancient port of Faifoo [Hội An], capital of the province, the ruins of the ancient Cham cities of Singhapoura and My-Son, the picturesque hill station of Ba-Na, perched on a ridge at 1,350m above sea level, and in Tourane itself, the Cham Museum.

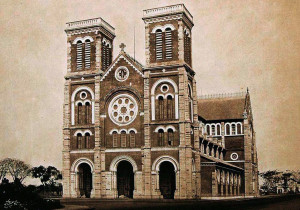

HUE — Hue is 107km from Tourane by rail and 105km by road; the railway follows the picturesque cliffs which line the bay of Tourane, and then the sea, while the road passes through the famous Col des Nuages (Pass of Clouds) at a height of 496m above sea level, offering a magnificent view of the bay.

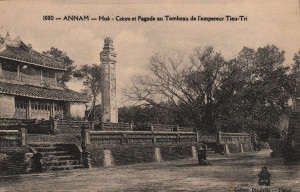

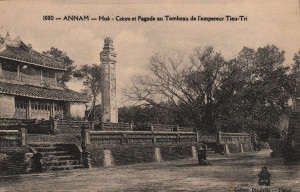

Hue, for two centuries the capital of the kingdom of Annam, is known for its beautiful location on the Perfume River, its Royal Palace and its Museum, but it is especially famous for its royal tombs. The kings of Annam seem to have considered their palaces to be simply guest houses in which they resided during their fleeting stay on earth. But to accommodate their everlasting souls comfortably and individually, each king built so-called tombs, which in fact resemble charming castles surrounded by graceful parks.

Hue – the tomb of King Thieu-Tri

Hue has a large modern hotel and one may find there all the resources of a big city.

HUE TO VINH — Either by road or by rail, the distance is about 370km.

Over the first 100km, road and rail hardly differ. From Dong-Ha (72 km from Hue), a main road leads to Laos (Savannakhet, 325km). At Dong-Hoi there is a hotel, a citadel, and a small woodcarving industry. At Bo-Trach, 17km from Dong-Hoi, a path leads to the deep caves of Phong-Nha, which one visits by boat, travelling inside the mountain over a distance of several kilometers. Road and rail split at Vinh. From here, the road follows the coast, the most picturesque point of which is the mountain pass called the Porte d’Annam (Door of Annam). The railway, meanwhile, enters a corridor formed successively by two picturesque valleys; it passes the Minh-Cam caves and runs between a series of large limestone rocks that remind one of Halong Bay.

In the corridor connecting the two valleys is the village of Tan-Ap, the starting point of a new railway currently under construction in the direction of Thakhek on the Mekong River. This route can now be partially traversed by the construction service line.

The line from Hue to Vinh then descends the Huong-Khe Valley.

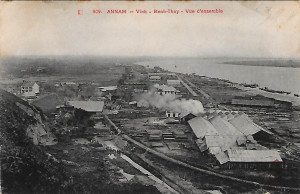

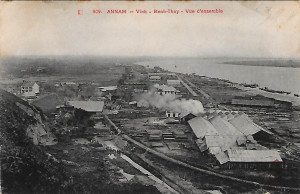

An aerial view of Vinh and Ben-Thuy

VINH AND BEN-THUY — This double agglomeration, comprising the administrative, commercial and military town of Vinh, and the port and industrial city of Ben-Thuy, is to become the second city of Annam and one of the country’s major ports. When the railway from Tan-Ap to Thakhek connects with the Mekong, that’s to say in five or six years, Ben-Thuy will become a potential trans-shipment point for travellers following the Hong Kong-Bangkok-Singapore route who fear sea-sickness.

In the meantime, Vinh and Ben-Thuy have some tourist interest as the starting point of two roads leading towards Laos, one via Napé to Thakhek, the other by the Tran-Ninh plateau to Luang Prabang (in part unfinished). The Tran-Ninh plateau, with its average altitude of 1200m, is very interesting from a touristic point of view, being a centre for forestry, agriculture and mining.

In addition, some 80km north of Vinh, are the hunting grounds of Phu-Qui (elephants and wild oxen).

VINH TO-HANOI. The 325km journey by train from Vinh to Hanoi is somewhat monotonous; it is best made by night train. In contrast, the road offers real interest to the motorist, particularly the section beyond Thanh-Hoa, provided one is happy to do a few zigzags. Thanh-Hoa, formerly a royal city and now the capital of a very beautiful province, possesses one of the most beautiful Vauban-style citadels. Here the traveller will find two guest houses – one of them European – and several garages. From Thanh-Hoa, one can visit: Sam-Son, a pretty and popular beach resort with a French hotel; Bai-Thuong, the starting point of one of the largest irrigation services; the ancient citadel of the Ho kings; the royal tombs of Trieu-Tuong; and the Pho-Cat Pagoda.

Limestone cliffs on the Day River, Ninh-Binh

Both road and railway travel across the border from Annam to Tonkin through a pass between limestone massifs, and in Ninh-Binh lead to the delta of Tonkin. Near Ninh-Binh the visitor will discover a veritable “Halong Bay on land” where, thanks to the high ground, rice fields have taken the place of the sea.

In Ninh-Binh, tourists may leave the main highway, making a 21km detour to visit the curious Phat-Diem Cathedral, built 30 years ago by an Annamite priest known as “Father Six,” and then retrace their steps to rejoin the road to the north, which, via Phu-Nho-Quan, connects with the road from Hoa-Binh to Hanoi.

It’s not the smoothest road, and it subjects both the automobile suspension and the travellers’ kidneys to a certain test. The landscape on either side of this little-known road, with its limestone rocks, is very picturesque, but what will impress the traveller most are the coffee plantations and mines which are testimony to over 30 years of hard work by the French settlers of the region.

The route we suggest between Thanh-Hoa and Hanoi involves a distance of 320km, instead of the more direct route of 150km. However, the traveller with insufficient time to do this longer route could still extend the direct route by about 30km, in order to visit the important manufacturing town of Nam-Dinh, the “Manchester of Tonkin,” with its mills and factories weaving silk and cotton, not to mention its distillery, rice mill, tile factory, numerous small native workshops and active river port on the deep arroyo which brings together two important waterways: the Red River and the Day River.

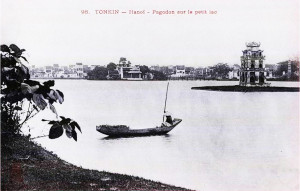

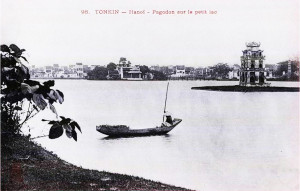

Hanoi – pagoda on the central lake

HANOI — We have just arrived in Tonkin from the South. The traveller coming from Hong Kong or the ones who were content to visit the south and perhaps Angkor, arrive here by passenger ship to Haiphong for a two- to five-day stopover in Tonkin. But other than the busy traveller whose limited time permits only a visit to Halong Bay, Hanoi, the capital of Tonkin and Indochina – that beautifully placed hub of all roads, railways and waterways – is an obligatory tourism centre for the visitor who wants to see Tonkin in detail.

The city of Hanoi itself is very attractive, with its enchanting central lake, its large green boulevards and its well maintained public gardens. Both European and Annamite trade here is very active; Hanoi’s shops offer all the resources of a large city in France, and its numerous hotels boast more than 250 rooms. It also has an opera house, five cinemas, native theatres, pavement cafés and dance halls, as well as numerous sports circles offering many amenities. There are also countless Annamite garages which lease automobiles.

The old indigenous town with its specialised streets, its Chinese and Annamite shops and small-scale industries, is perhaps the most curious in Indochina. The cultured tourist will also find several museums and libraries: the EFEO Archaeological Museum, a Geological Museum, a Commercial Museum, a Central Library, and an EFEO Library.

The surrounding areas are full of unusual pagodas and communal houses, located in villages devoted to picturesque industries. Some 25km from the city may be found some interesting caves with associated pagodas.

An aerial view of Cascade d’Argent (Tam Đảo) in colonial times

Around 50km west of the city, the delta gives way to dense forest populated more by wildcats than people, interspersed with coffee plantations. Continuing along this road leads the traveller, at km 110, into the beautiful valley of the Black River, almost unknown to the casual tourist, which is only ever frequented by that rare species, the “sports tourist.”

On the other side of the Red River, 80km from Hanoi, at 930m above sea level and connected to the road network of the delta by a beautiful highway, stands the hill station of the Cascade d’Argent [Tam Đảo], situated amidst a chain of mountains ranging in height from 1,250m to 1,400m which juts into the delta . There is a large hotel with 50 rooms, and some 50 villas permit hundreds of French families to go there tp escape the heat of summer.

In fact, Tonkin lacks nothing in summer resorts. Situated 290km by rail and 35km by automobile from Hanoi, Chapa [Sapa], situated at 1,600m above sea level in front of a mountain of 3,150m, offers two military hotels, two civilian hotels and many villas.

At the Chinese border, 25km from Langson (140km from Hanoi by rail), the small hill station of Mao-Son is situated 1,500m above sea level.

Lai Châu on the Black River

Hongay, in Halong Bay, and Doson, situated 27km from Haiphong, also have comfortable hotels.

We must also include among Tonkin’s tourist attractions the picturesque but inaccessible valley of Song-Chay, which will interest the sports tourist. Meanwhile for the soft tourist, we recommend an easy circuit which can be made by automobile. Leaving the Delta at Thai-Nguyen, the road climbs up the beautiful valley of Song-Cau to Bac-Kan and beyond continues towards Lai-Chau on the Black River (Tonkin), Reached via the Pia Ouac massif, the beautiful province of Cao-Bang offers several excursions, including the spectacular Ban-Gioc waterfalls.

From Cao Bang, return via Lang-Son and Phu-Lang-Thuong. This tour will take four days if from Bac-Kan one makes a small detour to the beautiful Babé Lakes with the Pung caves and Song Nang falls; if one explores a little the Pia Ouac massif to visit various tin mines; and if from Cao-Bang one tours a little to the north of this picturesque province. In Cao-Bang one may find a pretty good guest house, and in Lang-Son a European hotel.

HAIPHONG — Haiphong is new, modern, and perhaps a bit severe, but it certainly doesn’t deserve the scorn of M Dorgelès, who described it as “a small sub-profecture arisen from the mud.”

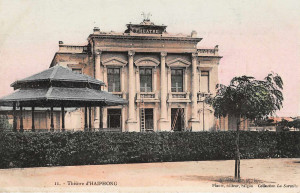

That small sub-prefecture is in fact a large manufacturing and commercial city of 110,000 inhabitants, clean, well-designed, with four or five medium-range hotels, a theatre, two cinemas, several garages, many modern shops, five very well installed banks and numerous cement factories (output 200,000 tonnes per year). It also boasts two glassworks, four or five rice mills, several mechanical, shipbuilding, spinning and weaving workshops, oil factories and tanning mills.

Haiphong Municipal Theatre

As for emerging from a swamp, this is precisely what this port of Tonkin boasts. The hub of several shipping lines from Hong Kong, Canton, Saigon, Marseille, Dunkirk and Nantes, Haiphong, though not favoured by nature, is very well equipped and very active. It was the French who created it. And it is certainly worth seeing.

But Haiphong is also close to Halong Bay, and the latter will in future be of great interest to global tourism. The day will surely come when the number of Tonkin-Hong Kong passenger ships visiting the bay will be less modest, and the facilities in Hongay will be sufficient to persuade the major tourist companies to include Halong Bay in their round-the-world cruises.

From Haiphong one travels to Hongay, the port of Halong Bay, either by road or by comfortable boat, both within two hours. This slowness adds to the charm of the trip, because part of the journey is through the famous bay.

Hongay has a large hotel, and opposite the town, in the village of Va-Tchay [Bãi Cháy] on the île au Buissons, one may find a good clean Japanese restaurant with several rooms. It is also at Va-tchay that the Cercle Nautique is based; it makes available its squadron of motorboats and sailing boats to members of the circle and their guests. The Hôtel des Mines in Hongay also owns a few boats which are made available to tourists; but if the group is large enough, visitors may rent in advance one of the larger vessels owned by the Société anonyme de Chalandage et Remorquage d’Indochine (SACRIC) – these are real cruise ships in miniature, and very comfortable.

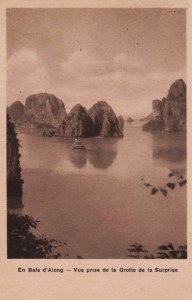

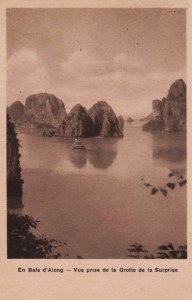

Halong Bay

Halong Bay, praised in both verse and prose by countless writers, photographed endlessly, and subject to intensive propaganda, ranks among the most beautiful places in the world; Unfortunately, the tourism organisation there has long been too rudimentary; links with Hong Kong are by small steamships that contrast greatly with the large passenger vessels which bring most tourists to Tonkin. It is not advised to visit the bay during hot season (early May to October).

We will not describe Halong Bay here. Suffice it to say that, during the right season, from October to late April, one can zigzag through its islands and fjords for at least two or three days without tiring of the ever changing landscape.

On the other hand, Halong Bay, with its open cast coal mines, also provides economic interest of the highest order.

LAOS — Having traveled through all of maritime Indochina, the curious tourist who wants to know the country in detail will want to see the land on the other side of the mountains, this Laos which he has heard to be one of the most interesting countries of Indochina. Interesting, certainly – by virtue of its gentle and indolent population, more inclined to pleasure than to work, and their customs and picturesque costumes. As for the landscape, if you believe the enthusiastic claims of certain tourism company advertisements, you may be disappointed.

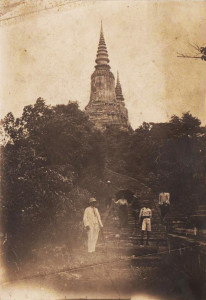

Above all, one should avoid travelling up the Mekong, the great river which passes through that country over a distance of nearly 2,000km. If one wishes to see the highlights of Laos, and in particular the kingdom of Luang Prabang, which is the most interesting region, one should first go to Bangkok in Siam and take the train to Lampang.

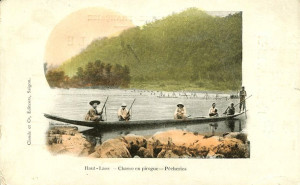

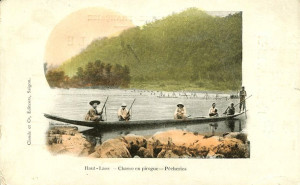

Fishermen in northern Laos

Then take a three-day automobile trip to the Mekong in Xieng Sen, opposite Ban Houei Sai. From Ban Houei Sai one can descend the Mekong, either by raft or by motor boat, to Luang Prabang (hotel) and Vientiane (hotel), where a steamship may be taken to Khone (waterfall) and Phnom Penh.

One may also join the Mekong in Thakhek (hotel), starting from Vinh (northern Annam), either via Napé or by taking the service road of the future Tan-Ap-Thakhek railway.

Finally, one can leave the coastal railway at Dong-Ha to join the Mekong in Savannakhet and catch the steamboat there. Downstream from Thakhek, the Kemmarat rapids are interesting to see during the descent, even if they are rather tedious to climb. But the most scenic spot in this part of Laos is undoubtedly Pakse, with its beautiful road which leads up onto the Bolaven Plateau (1,250m above sea level) and the ruins of Bassac.

From Pakse, one can either continue to Phnom Penh and Saigon by boat, or, in the dry season, by car. Alternatively, one can return to Siam (125km by automobile) via the city of Oubon, on the Bangkok and Penang railway.

We will conclude by making some recommendations to the tourist coming to Indochina.

Savannakhet in colonial times

Make sure that you allow enough time to see everything, and try to schedule your trip in such a way that you can see every country in the cool season – this means avoiding Cochinchina and Cambodia in March, April, May and June, Tonkin from the end of April to September, and Annam from late September to late November.

Finally, make sure you take along a good guidebook – we recommend the Madrolle guide to Indochina – To Angkor in English, and Baie de Halong, Saïgon et Tourane, Indochine du Nord, Indochine du Sud, Siam et Angkor in French. These works, designed by the famous Boedecker, are the most complete and the most accurate.

Ruins at Angkor

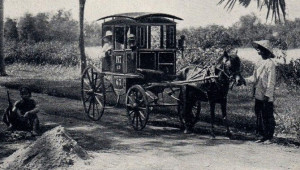

The Grand Hotel in Phnom Penh

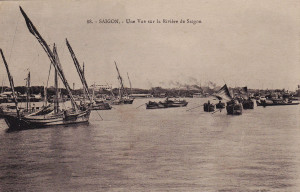

Saigon – entrance to the arroyo Chinois

One of the gates into the Huế citadel in the 1920s

The Bank of Indochina, Hanoi

Buddhas in the Ky-Lua caves at Lang-Son by Dieufils

Cao-Bang province in colonial times

That Luang in Vientiane, Laos

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebooks Exploring Huế (2018), Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (2019) and Exploring Quảng Nam (2020), published by Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.