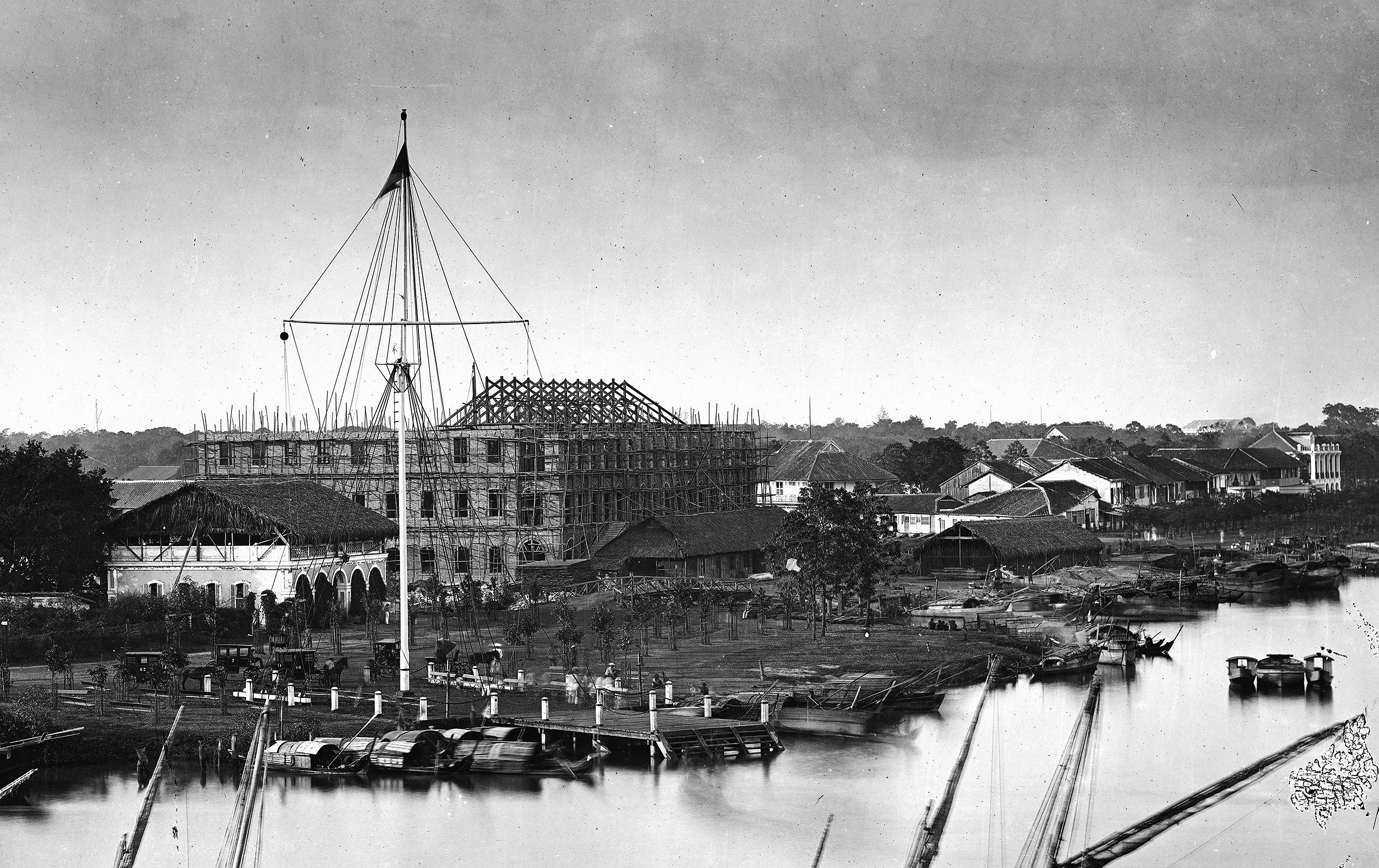

This 1867 photograph by John Thomson shows the Maison Wang-Tai under construction

One of the more mysterious figures of the early French colonial period, wealthy Cantonese trader Wang Tai is remembered principally as the owner of the city’s grandest building, at a time when the Admiral-Governors of Cochinchina still lived in a very modest wooden residence. But the man usually described as a successful brick manufacturer turns out to have made his fortune from the lucrative opium trade

Little is known about the life of Cantonese trader Wang Tai, other than the fact that he was born in 1827 and arrived in Saigon-Chợ Lớn in 1858, on the eve of the French conquest.

He was clearly a man of some wealth, and by the 1860s he owned two large and successful brickmaking factories on the banks of the Lò Gốm creek in Chợ Lớn, which went under the company name Briqueterie Wang-Tai. During the late 19th century, as Dr Nguyễn Đức Hiệp showed in his 2010 article Wang-Tai là Ai? (Who is Wang-Tai), his company supplied bricks and tiles for the construction of several of Saigon’s major civic buildings, including the Cathedral (1880).

The Maison Wang-Tai

The first Hôtel du gouverneur was a collection of wooden buildings imported in kit form from Singapore and assembled on site in 1861-1862 for Admiral-Governor Louis Adolphe Bonard (28 November 1861-23 April 1863)

Today, Wang Tai is perhaps best remembered for the large brick residence and headquarters he built for himself in 1867 right next to the Saigon River, on the site now occupied by the Hôtel des douanes (Customs Department). Known as the Maison Wang-Tai or Hôtel Wang-Tai, this building is said to have been the cause of some annoyance in the upper echelons of the colonial administration, because, despite being “the residence of a native,” it was in fact far grander than the first Admiral-Governor’s Palace – a series of three wooden buildings imported in kit form from Singapore!

In December 1869, when King Norodom of Cambodia paid his first official visit to Saigon at the invitation of the Cochinchina authorities, there were still no proper hotels in the city, so the king stayed instead in the “sumptuous apartments which had been prepared for him at the Hôtel Wang-Tai, owned by a Chinese.”

It seems that, from the outset, Wang Tai intended his headquarters to serve both for his own use and for rental to outside tenants, for by the early 1870s a number of French organisations were also renting premises within the Maison Wang-Tai. Chief of these was the Saigon Municipal Council, which, following its establishment in 1869, occupied a series of temporary homes before moving into a permanent building in 1909. The Hôtel de ville or Town Hall was based at the Maison Wang-Tai from the late 1860s until the early 1880s.

Another important colonial institution which rented premises here was the Cercle de l’Union, described in 1883 as “the rendezvous of all the colonial gentry.”

After 1874 the Maison Wang-Tai appears in the records as the Cosmopolitan-Hôtel and Café

In January 1883, the Société de géographie de Lille Bulletin published an account of the “Famous Maison Wang-Taï,” which described the building and its occupants in detail:

“A Chinese man named Wang Tai, who is known to everyone in Saigon, built a large house with a classical portico called the Maison Wang-Tai at the angle of the Arroyo Chinois and the grand Arroyo; this place is almost the centre of Saigon. The house has two floors with verandahs and it contains the Town Hall, the residence of the Mayor, who is the best-lodged official in all of Saigon, a central police station, the secret police (a new institution created in Saigon) and the large Cercle de l’Union, which counts almost all officials and naval officers of Saigon and, in small numbers, the Marine infantry, but very few traders. That’s because the traders have their own Cercle du Commerce, which is less important than the Cercle de l’Union. Almost the entire first floor of the house facing the arroyo is occupied by the Cercle. In the evening we can see brightly lit windows; regulars of the Cercle play games or walk along the verandah smoking; this is about the only place to go in the city when the night comes and we see many Europeans here.”

By 1874, Wang Tai himself seems to have moved his office and residence out of the building, since in that year the Maison Wang-Tai appears in the records as the Cosmopolitan-Hôtel and Café, managed by one David Austin. Before the opening of the famous Hôtel de l’Univers on rue Turc in the late 1880s, the Cosmopolitan-Hôtel was the only place in Saigon where wealthy visitors could expect European-style comfort and service.

However, this did not prevent the area around the hotel from developing a rather seedy reputation. One visitor’s account of 1882 refers to Saigon’s very large number of “houses of ill-repute,” which were “all grouped immediately behind the Cosmopolitan-Hôtel, in the rue des Fleurs.” This alley still exists today, behind the Customs Department building.

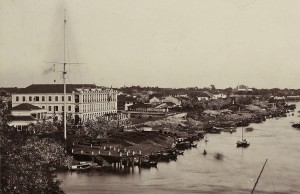

Emile Gsell’s 1880 photograph shows the Maison Wang-Tai on the Saigon riverfront

Wang Tai was clearly a figure to be reckoned with amongst the new wave of Chinese settlers encouraged by the French, and by 1880 he had become the “Chief (Bang trưởng) of the Cantonese congrégation.” While occupying this post, he argued vociferously on behalf of Chinese interests, as indicated by an account of a successful request he brought before the Colonial Council in 1883 to abolish the amount of land tax levied on “five Chinese pagodas in Cholon belonging to various congregations in the city,” arguing that “Indian mosques and pagodas already enjoy that favour in Cochinchina.”

Opium king

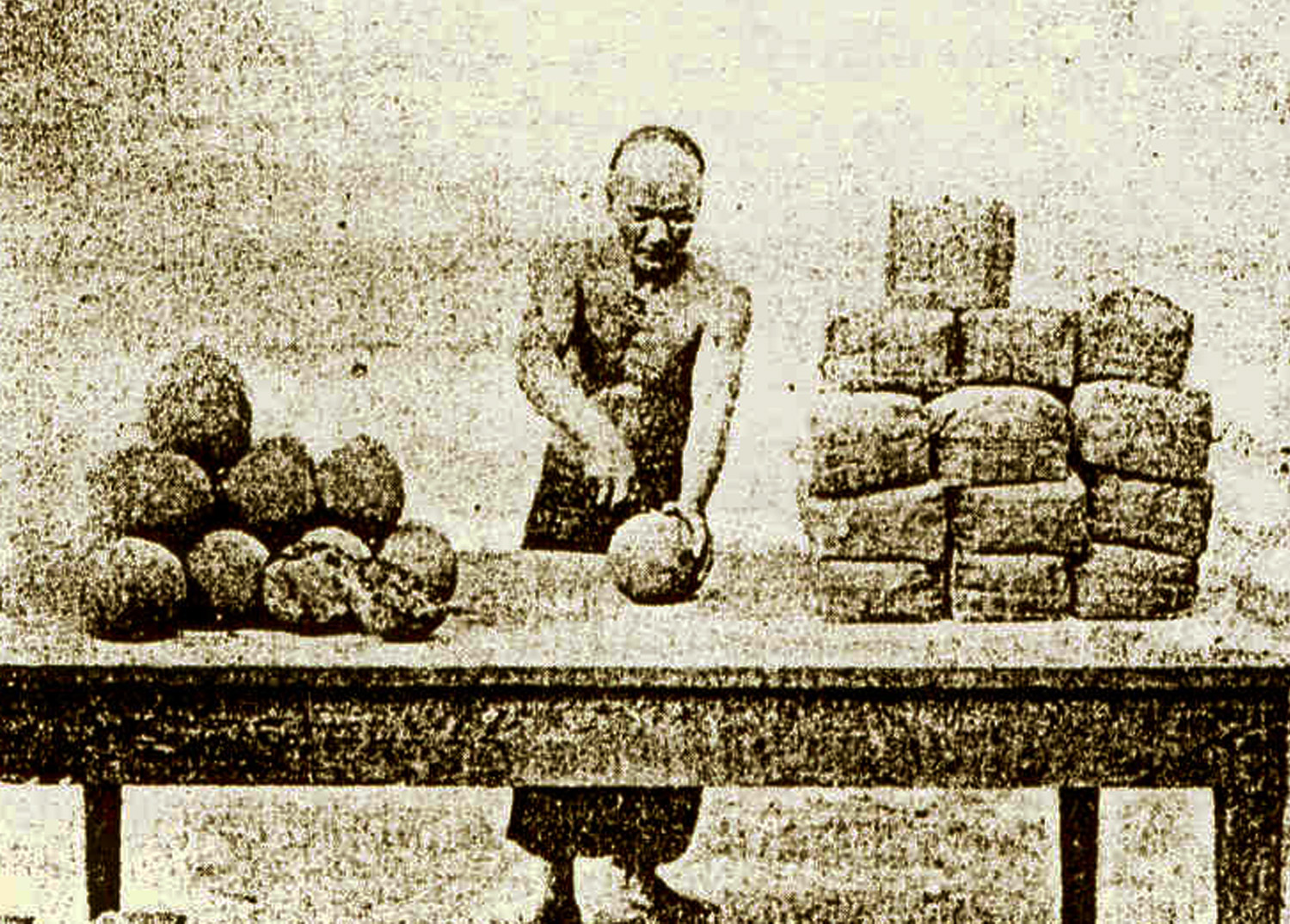

A closer look at the colonial records reveals that Wang Tai’s fortune was made not from his brick and tile making factories, but rather from his role as chief supplier and processor of raw opium for the Cochinchina government.

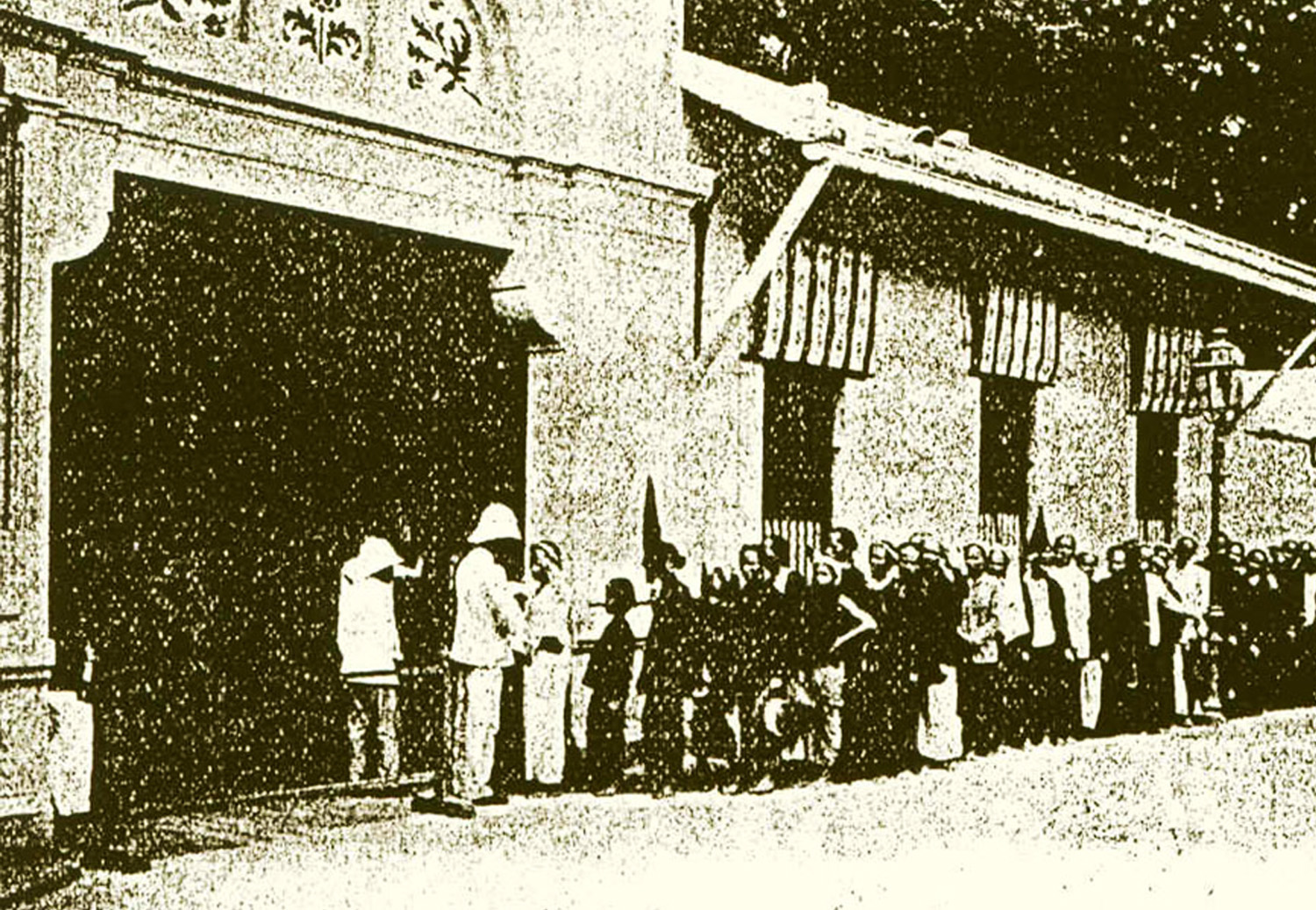

As early as 1862, the French authorities set up an opium franchise, with the aim of maximising revenue and turning their new colony into a going concern. At the outset, raw opium was imported from British India via various merchant houses and processed in a network of small processing factories in Chợ Lớn, before being sold to consumers through a network of licensed opium dens.

However, by the mid 1860s, Wang Tai had taken over both the shipping and processing of opium, making himself a small fortune in the process. At the height of its drug shipping and processing activities in 1881, the so-called Marché Wangtaï “shipped 864,000 taëls of opium and sold it at 2 cents per taël to the government,” before processing the resin into smokable chandoo in its own network of factories.

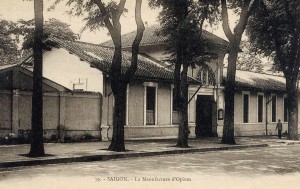

The Manufacture d’Opium at 74 rue Nationale (now Hai Bà Trưng street) Saigon, which opened in 1881

In 1881, realising that Wang Tai was getting rich at its expense, the French administration moved to break his drug monopoly. Shipping of raw opium was opened to competitive tender and a new factory named the Manufacture d’Opium was opened at 74 rue Nationale (now Hai Bà Trưng street) in Saigon to process the resin.

In his De Toulon au Tonkin (itinéraire d’un transport) of April 1885, Dr Bernard describes how “The opium trade was formerly leased by the State to a rich Chinese merchant named Wang-Tai, who had a monopoly in Cochinchina and took for himself an annual profit of several million. Thankfully, the French administration has since changed its policy and the opium trade has been brought under state control. This was a successful reform from a social and political point of view, and especially where the financial report was concerned. This state opium monopoly has indeed given us last year a very respectable income of 8.6 million francs!”

After 1881, Wang Tai continued to ship and process opium on behalf of the Cochinchina authorities, though now simply as one of many trading houses which competed with each other for the work. In 1885, during one tendering exercise, a member of the Colonial Council commented: “The Administration may judge from the competitors, and I know one – he has made outstanding reports to the Governor and to the Director of Customs and Excise about opium, and would certainly quote more cheaply than Mr Wang Tai; although I should add that the Annamites [Vietnamese] really appreciate the opium produced by Mr Wang Tai.” In 1887, Wang Tai still appears in the Annuaire de la Cochinchine française as an opium producer (M Wang-tai père, Fabricant d’opium, rue Catinat).

In 1882 the French authorities purchased the Maison Wang-Tai to house its Directorate of Customs and Excise (Direction des Douanes et Régies)

After he lost the Cochinchina opium monopoly, the records tell us less about Wang Tai’s involvement in the opium trade and more about his other businesses. By 1886, according to the Annuaire de l’Indo-Chine française, in addition to his two brick factories, Wang Tai owned a rice processing plant on the Lò Gốm creek and had an import-export company based on quai Gaudot (Hải Thượng Lãn Ông street) in Chợ Lớn. He also maintained a Saigon trading office, Wang-taï père el fils, on boulevard Charner.

It was perhaps somewhat ironic that in 1882 the French authorities decided to purchase Wang Tai’s former headquarters, the Maison Wang-Tai, to house its Directorate of Customs and Excise (Direction des Douanes et Régies), the government agency which controlled the lucrative French opium franchise.

In 1882 Wang Tai sold the building to the government for the sum of 200,000 Francs, and in subsequent years the Directorate of Customs and Excise relocated there, along with the Commercial Port Telegraphic Office. In 1885, one commentator noted that “the Maison Wang-Tai, an immense construction built by a rich Chinese, now belongs to the Customs and Excise Administration, which has established its offices there.”

However, it seems that the Maison Wang-Tai was not big enough for the Directorate of Customs and Excise, for by 1887, at an additional cost of 100,000 Francs, it had been rebuilt to a design by Alfred Foulhoux as the Hôtel des douanes (Customs Department), the building which still stands today.

By 1887 the Maison Wang-Tai had been rebuilt to a design by Alfred Foulhoux as the Hôtel des douanes (Customs Department)

The decoration of this new building reflected its main source of income and perhaps also paid tribute to its origins as the former home of the government’s chief drug supplier: writer, journalist and Indochina specialist Jules Boissière (1863-1897) pointed out that the badges between the windows included opium poppies, by the 1880s one of the most important revenue streams for the Cochinchina government.

Wang Tai’s later years

In November 1888, the Tablettes coloniales: organe des possessions françaises described a grand celebration held that month “to celebrate the 61st anniversary of the birth and the 30th year of residence in Saigon of a Chinese merchant named Wang-Tai.” Organised by “the son of Wang-Tai and family, his countrymen and his friends” and featuring “illuminations, fireworks and theatrical performances,” it was attended by “French and Europeans from Saigon, Cholon and the interior… indeed, the entire European colony responded to this gracious call.” It went on: “Wang-Tai is one of the most esteemed Chinese notables of Saigon; he has given not only his countrymen, but also the French administration and settlers, great service. It is apt that we have recompensed him by participating in this peaceful celebration of which he has been the object.”

The Saïgon Républicain newspaper of 10 November 1888 gave a more detailed account of this event, entitled “An anniversary:”

Festivities on boulevard Charner

“The sons of Monsieur Wangtai – Wangtai Suon, mandarin; Wangtai Foo, trader in Cambodia; Wangtai Suu, trader in Saigon; Wangtai Pio and Wangtai Xuong, students in China; Wangtai Khai (Cambodia); and his other sons, Wangtai Sing and Wangtai Thang, celebrated with dignity the 61st anniversary and the 30th year in Cochinchina of their father, a trader in Saigon, having invited all of the colony to participate last Saturday in a soirée organised to that effect.

An immense marquee decorated outside and inside with tricolour flags, beautiful curtains and draperies in silk embroidered with gold Chinese letters, calligraphic art and fantastic dragons, was built on boulevard Charner. For eight days, gifts flowed to our fellow citizen Wangtai, because he is, as we know, a naturalised Frenchman – and the gifts came not only from Saigon and Cholon, but also from Cambodia, Siam, and even from deep in China. They consisted of pieces of silk, furniture inlaid with mother of pearl, animal reproductions, artistically crumpled fabrics, jewelry and also – a touching Chinese custom – bank notes.

From 9pm until 1am the next morning, visitors came here in droves! Military music lent its support to this solemnity. We were received by Wangtai, who looked like the elder brother of his sons. This patriarch of the Yellow River was surrounded by his children and grandchildren, in full ceremonial dress of richly embroidered black silk. The youngest of his offspring knelt before the guests and made the mandatory kowtow. We French are not alone in having invented honest civility!

In the huge room, many tables were dressed. We were pleased at the valiant way in which all these great things had so kindly been offered. The most charming women of Saigon had also provided an excellent champagne in honour of the 61 year-old Wangtai. Lucky for Wangtai!

At about nine o’clock, the Governor General and Madame Richaud, accompanied by Captain Dol, made an appearance for a few moments. The Saigon Républicain newspaper wishes you health and happiness, citizen Wangtai!”

Another image of Alfred Foulhoux’s Hôtel des douanes (Customs Department)

In 1889, Wang Tai, now also the recipient of a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur, built himself a large house for his retirement on the quai de l’Arroyo-Chinois (route coloniale no 3).

Unfortunately, his dignified retirement didn’t last long. In 1891 Wang Tai’s name was dragged through the mud when the Avenir du Tonkin and Indépendance Tonkinoise newspapers revealed a secret deal between him and Monsieur Coqui, Director of Customs and Excise for Annam and Tonkin, whereby the authorities had agreed to turn a blind eye to smuggling in return for “money and gifts” from the veteran Chinese trader.

While the scandal which followed clearly disgraced Wang Tai himself, it seems to have done little to dent the success of his family’s other businesses. The Briqueteries Wang-Tai continued to operate successfully and were singled out for praise as an example of Cochinchina industry in A Challamel’s 1910 book, Histoire de la Cochinchine française: des origines à 1883.

Workers queueing outside the Manufacture d’opium in the late 19th century

A worker cutting balls of opium resin

Writer, journalist and Indochina specialist Jules Boissière (1863-1897) pointed out that the fenestration decoration on Foulhoux’s Customs House (the rebuilt Maison Wang-Tai) included opium poppies

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.