Saigon Cathedral in the early 1900s

Belgian travel writer Emile Jottrand clearly didn’t stay long enough to get a true picture of the city, but her account of Saigon and Chợ Lớn in 1900, published in the book Indo-Chine et Japon, journal de voyage (1909), contains a few interesting observations

15 October 1900

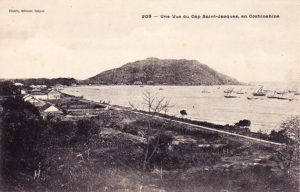

Thus passes our quiet stay at Cap Saint-Jacques. We have no extraordinary adventures to relate; neither are we obliged, like the guests in our neighbouring hotel, to defend ourselves against a one-metre-tall monkey.

The baie des Cocotiers, Cap-Saint-Jacques (Vũng Tàu)

Nor against the Annamite gendarmes, who arrested an Austrian adventurer couple aboard a steamer when it passed the Cap. We don’t even have to protect ourselves from the rain, the rare showers graciously choosing to fall at siesta time, thus preparing for us a fresher and more pleasant journey. As for the temperature, it is always 25 to 28 degrees, that’s to say perfect, with plenty of fresh air and plenty of shade.

We leave at 9am. A carriage takes us with our luggage to Binh-Dinh, and for the last time we see the pretty road, lined with tranquil lotus ponds, cactus hedges, Annamite temples. Shall we ever return to this beautiful corner of the world?

Just as we reluctantly depart the baie des Cocotiers, we see a gunboat at anchor, the Styx, which has just arrived. It is newly built and carries state-of-the-art equipment. However, we learn that gross miscalculations were made in its construction, and that as a result, the gunboat has unstable equilibrium. For that reason, it cannot sail the high seas, and in fact hardly renders any service at all. The gunboat is currently being used to supply the Chasseloup-Laubat, which has been quarantined downstream from Saigon. What a waste! Several millions thrown into the water!

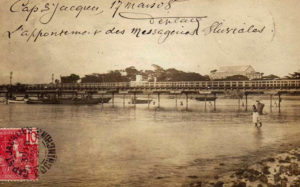

The Messageries maritimes wharf at Cap-Saint-Jacques (Vũng Tàu)

My colleagues cannot understand why I am surprised, citing all the other monumental gaffes – bridges we must remake, buildings whose plans get redrawn five times – which we hear about every week, gaffes which are surely only the tip of the iceberg!

Along the road we pass carriages with uniformed coachmen and see a dashing Annamite aide-de-camp waiting on Monsieur Paul Doumer, Governor General of lndo-China. And indeed, shortly after leaving the Cap, we see his ship, the Laos.

We reboard our excellent Chinese boat. On the pier, they are selling lobsters, which squirm in baskets.

The journey is uninspiring all the way to Saigon. By way of diversion, we are served an excellent tiffin, and are entertained by the boarding of local vendors arriving from villages on the nearby arroyos. Our boat slows down for them, but does not stop.

Our eyes follow the flight of some brightly-coloured birds, whose plumage contrasts with the universally muddy and dreary landscape.

The “Tour de l’Inspection”

Finally we catch sight of the twin towers of Saigon Cathedral, which begin their annoying hide and seek game. After one last detour, we reach Saigon port.

Our hotel is very crowded and we are given poor rooms in which we find ourselves suffocating after the fresh air of the Cap. Fortunately we will not be here for long.

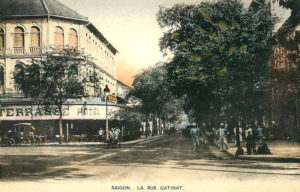

It’s 5pm when we set off for a sunset walk, Saigon’s traditional “Tour de l’Inspection.” Excellent roads, nice scenery. elegant ladies and their officer husbands in superb carriages driven with finely dressed teams of horsemen. We leave at dusk, and on the return journey Saigon dazzles us with its lights. The vast rue Catinat is lit with electric globes, its great cafés competing with each other to have the best illumination and attract the most customers.

Entering one of these cafés, sitting at a marble table and ordering a cherry-gobbler cocktail, one may believe oneself to be in Europe, and the illusion is complete when an urchin comes to sell his roses and a hawker his trinkets.

Rue Catinat, Saigon

We return on foot to our hotel, watching scenes much like those we would see in Paris.

Saigon is a city so European, so French, that we encounter relatively few local people in the streets. It seems a very quiet and pleasant place, with traffic on the streets extremely moderate, just like on the river. We are a long way from the New Road in Bangkok!

It should be noted, moreover, that out of some 2,500 Europeans in Saigon, officials and their families number about 2,000. Of the remainder, only around 150 are traders, and all of those are suppliers to the above officials. There is no trade or industry; heavy customs tariffs, according to what I am told, have killed Saigon and all Indochina. People speak to me of a golden age, long ago, when business boomed, but since the establishment of protective tariffs, bankruptcies have occurred in quick succession.

Such is the outcome of a policy devised by small-minded politicians who want to squeeze and drain the French colonies to please a small number of powerful voters – cloth merchants from Elbeuf and silk merchants from Lyon, people who are still unable, despite the excesses of the system created on their behalf, to counter the threat posed by imports from Germany and other foreign competitors.

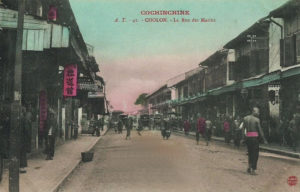

Rue des Marins, Chợ Lớn

In the evening we go to Cholon, the Chinese city located along an arroyo, 5 kilometres from Saigon. This is undoubtedly the most important commercial city in all of Indochina. While it is home to fewer than 100 Europeans, Cholon contains 60,000 Annamites, 40,000 Chinese, 150 Indians and 15 Cambodians. It is the place where immense Chinese fortunes have been made, through prodigious activity by the “Celestial Ones,” whose business methods always confound the European.

When we arrive in the city it is already late, and many shops are closed. We admire the wide streets, the spacious sidewalks, the air of ease that reigns everywhere. There are also cafés in the French style and everything which can please the European of Saigon; because, despite all the nonsense that is written about the Chinese, there is no race of people more eager for foreign invention, as long as commercial advantage is to be gained.

The elegance, the wealth, the order of the Chinese stores in Cholon is beautiful to see. Elaborately carved and gilded wooden signs and outdoor lanterns compete with each other to be the most brilliant and elegant, all for the cause of attracting the dollar! But the newcomer who believes Cholon to be a typical Chinese city would be a mistaken, judging by what we saw in Peking and Canton.

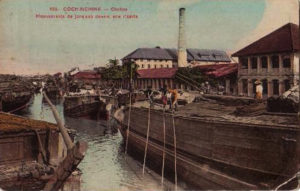

Barges on the arroyo Chinois in Chợ Lớn

Nothing is more curious than the history of this city; for it shows how persecution can help build a strong and powerful race.

In this country, less than a century ago, the Chinese were treated as outcasts; the Emperor of Annam forbade them to settle in his territory without the special permission of the court. Their number in villages was limited by regulation and they could not own property without a licence. They were forbidden to export products other than rice, and they paid high taxes on all things (see H L Jammes, Souvenirs du pays d’Annam, 1900).

Settling in Cholon, which was initially a ghetto, a place of outcasts, they grouped together their business interests. And thanks to their secret associations, the enormous unregulated power of which we cannot conceive of in our own country, they soon dug canals, deepened rivers, created docks, built industrial plants, opened schools and even higher education colleges, lit their streets, and built roads and bridges, without help of persons other than themselves. This is what the Chinese have done in a country where they were once banned by the Annamites, where they are still frowned upon today, where they are taxed heavily just because they are Chinese.

A rice husking factory in Chợ Lớn

They did all this without a penny of subsidy, welcoming the Annamites who had formerly proscribed them, and attracting foreign commercial benefits. However, in Saigon, just an hour away, the French colons are still very confident, and will be for a long time yet, in their belief that it is impossible to build a street or open a school without some paternal government support!

In the city of Cholon there are eight large rice husking plants. This is of course the biggest industry in the area. The factories are owned by the Chinese and they work day and night, using machinery which came from England. They make, it seems, huge profits. Together they can produce 7,000 tonnes of rice per day – note that in 1898, Siam exported 2,000 tonnes per day. A new factory will be built this year. The factories are fuelled by rice husks. Unhusked rice, which is also eaten here by animals, is called “paddy.” It enters the factory in that form and leaves as white rice, such that we find in the shops.

Cholon also has brick kilns, potteries, sawmills, dry docks and boat-builders. One also finds here every kind of trade, including jewelers, keymakers, cabinet makers, tanners, dyers and blacksmiths, along with importers of teas, silks, embroidery and other fabrics. All of these professions and all these trades are the preserve of Asians.

16 October 1900

The Nestlé building at the lower end of the rue Catinat

This morning we start to explore the city of Saigon, the plan of which is simple: the streets generally intersect at right angles and the city is built in squares. We do not see in the urban area any market gardens or sugar cane fields as in Bangkok.

For us Europeans, a city is hardly worthy of the name without having a perfect road network, and that of Saigon is excellent.

But what is missing here, which we regret, are the glazed roofs of gold, green and purple palaces and temples; the disorder of native huts scattered in villages; the canals with their incessant traffic of various boats; the river with its junks and houseboats, and the locals cheerfully attired in light colours. Saigon presents, from the Asian point of view, no originality.

The most important street in the city is the rue Catinat, which divides the city in two. It is home to some fine shops, the Theatre, the Post Office and the Cathedral.

Cathedral square in the early 1900s

The Saigon Cathedral, which cost two million, is trivial at best. But all colonies pay royally for their civic buildings; through the incapacity of some, and the treachery of others, every public building costs two or three times its true value. They recruit architects who have never seen a plan, and entrust major projects to those who are unsuitable.

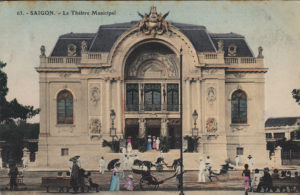

The Municipal Theatre, completed this year, cost about three million francs, though none of the 2,500 Europeans of Saigon seem worried about that! It is small and contains only 800 seats. However, it must be said that the building is graceful and successful in all respects, and the interior decoration is charming. The performing troupe has just arrived and we buy our tickets for the evening performance.

The Post and Telegraph Office occupies a nice, well laid-out and decorated building, but one which is copied from European models without any appreciation for the climate. I have already said in a previous chapter how the scarcity of wood here is a great obstacle to the construction of galleries, balconies and verandas. The chalet, so suitable in hot countries, is unfortunately absent from Saigon.

The Palais de justice

The streets are filled with public offices, we see nothing else! Such a large administration!! Yet how could it be otherwise, since according to official reports, Cochinchina has 66 civil servants for every 100 persons!

The Courthouse (Palais de justice) is rich and comfortable. I meet very few people here; in one chamber of the civil court, two lawyers are arguing a case before three judges, and all are in full robes! One of the lawyers pleads, with all the volubility of a Frenchman, a case concerning roads and public areas. None of the parties are present, and there are no curious spectators in the room. The hearings last from 7am to 11am.

To practise as a lawyer in Saigon, it is necessary to have a government permit. This is a monopoly; they are only 10 or 12 lawyers at the most and their positions are enviable. I am told that one of them earns 150,000 francs per annum.

If Saigon is in the doldrums, the lawyers are certainly not doing badly. The Saigon Courthouse has jurisdiction over appeals of the Consulate of France in Bangkok, and I understand that the Siamese government is afraid to become involved in any trials involving French subjects, because it would be too expensive!

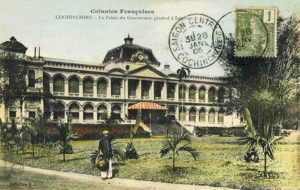

The Palace of the Government General

The Palace of the Government General is very grand. It is surrounded by a beautiful garden, where we see, growing and blooming with exuberance, all kinds of tropical plants and trees.

Apparently the reception rooms and apartments are very luxurious. It also appears that the looting of the buffet on the occasion of the 4 July Ball is truly a sight to behold!

Not far away is the Palace of the Lieutenant Governor of Cochinchina, also built with classical lines, but facing the street.

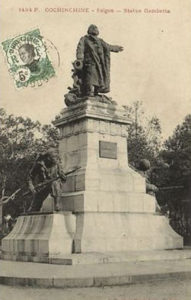

Suddenly, we see a surprising spectacle before our eyes, right in the middle of one of the city squares – a statue of a man in a fur coat, bareheaded, with a tanned complexion, haranguing the people. Fully occupied with his address, he recklessly exposes himself to the heat of the tropical sun, without appearing in the least bit troubled. Who is this crazy man?

The Gambetta statue

We approach curiously: it’s Gambetta! What bizarre circumstances led the old tribune to Indochina? No one could tell us … maybe he was lost en route to Paris or some other French city and they accidentally shipped him here, forgetting to remove his coat first!

Thus dressed, he seems to have been subjected to the torture once invented by Petrus to shorten the duration of parliamentary debates in Belgium … five minutes more and he will fall exhausted, begging for mercy!

At other places in the city we see further monuments dedicated to the memory of Admiral Rigault de Genouilly, who conquered Saigon in 1858; to Doudard de Lagrée and Francis Garnier, who explored the little known banks of the Mekong and sought its origins in the period 1866-1869; and finally to the Bishop of Adran, who acted as advisor to the Emperor Gia Long at the beginning of this century.

We do the “Tour de l’Inspection” again. Half way through our promenade, we find in the middle of the forest a pleasant café, around which much of Saigon’s elegant high society is clustered. Carriages line both sides of the road. We join them, thinking of the Laiterie in the Bois de la Cambre.

Back at the hotel, we learn with great pleasure that Monsieur and Madame Mottet have decided to accompany us to Angkor Wat, which is the main purpose of our little trip. The departure will be early tomorrow morning; meanwhile we go to the Theatre to see Carmen.

Saigon Municipal Theatre

The auditorium, full of men in dazzling white suits, presents an unexpected appearance. The ladies enhance and contrast that tonality with their low-necked dark, often black dresses.

Alone, absolutely alone, one man in a tuxedo may be seen: as he leaves, we see on the head of this social upstart a most extraordinary hairstyle, a true masterpiece. I thought this kind of perfection possible only in demonstrations by professional hairdressers.

During the intervals, as we walk to the foyer, we rediscover the joys of greeting in the French, or rather Latin, manner. Suddenly an English woman enters, swinging her arms, her chest trapped under a tight corset, her neckline timidly high, her hair bunched under an invisible hairnet. She greets while walking, sometimes almost running. How much prettier and elegant she would look in a simple tennis blouse!

In contrast, when the French woman is out on parade, she makes the most of her daring décolletage by arching her body and walking without fear. Back home she is relaxed, but when she goes out, the difference in her appearance is striking.

We are pleasantly surprised by the production of Carmen, which is performed very satisfactorily. All in all we are delighted with our evening and very jealous of the Saïgonnais, who can afford this pleasure three times a week!

During the first act there is a downpour so heavy that that we can hardly hear the choruses. Fortunately, these rains are usually as short as they are noisy; but it seems to me that a theatre season would be difficult to reconcile with a rainy season.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.