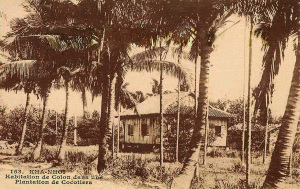

George Dürrwell spent nearly three decades working for the Cochinchina legal service. His 1911 memoirs, Ma chère Cochinchine, trente années d’impressions et de souvenirs, février 1881-1910 (My Dear Cochinchina, 30 years of impressions and memories, February 1881-1910) afford us a fascinating picture of life in early 20th century Saigon and Chợ Lớn. This is Part 1 of a three-part excerpt from the book.

Saigon has been described as the “Pearl of the Orient,”and all of those who have had the good fortune to live there or to visit the city – except, perhaps, for one or two Tonkinese chauvinists – are agreed that it deserves this graceful designation without any reservation. It is also the true capital of our French Indochina: a commercial capital with an admirable maritime location; a historic capital, to recall the happy expression once used by Governor General Beau, “to glorify our dear city and the unforgettable memories that its name alone evokes;” and finally a political capital, simply by birthright.

After arriving by ship at the Messageries maritimes wharf, early travellers passed through Khánh Hội en route for Saigon

The first impression on arrival in Saigon is not, in fact, the most engaging. After following the meandering path of the river, and contemplating for several hours its melancholy shores bordered by endless flat and monotonous rice fields, the traveller reaches, after a passage of 24 days, the pier of the Messageries maritimes.

There, in both sight and smell, he feels the perfectly unpleasant sensation of approaching a slum. For in front of him, right next to the dusty and often muddy road which leads to the old bridge across the arroyo Chinois [Eiffel’s Pont des Messageries maritimes], he encounters a shapeless mass of decrepit and lamentably rickety huts which emerge from pools of stagnant water, forming an ugly and unsightly view unworthy of the great city of which Khanh-Hoi is the suburb.

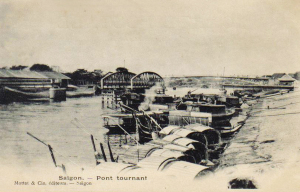

In fact, there is now a second bridge, known as the Pont tournant (Swing Bridge), over which passengers may travel to reach Saigon without passing through this ghetto, but it swings very badly. Some even claim that it doesn’t work at all; but those are grumpy and biased people who deserve no credit.

The joint road-rail swing bridge, opened in 1908

I can say, indeed, that I saw it open at least once, at a practical time which permitted the free movement of the public. But as the saying goes, “One swallow doesn’t make a summer.” This unfortunate bridge has thus acquired, from the beginning of its existence, a true local celebrity; and the rivers of ink that have been spilled talking about it are certainly more tumultuous than the waves of dirty water which agitate the river over which it was thrown.

But let’s hasten to flee this smelly suburb, taking either one or the other bridge over the arroyo which still separates us from the city. For when we reach Saigon, everything changes.

One of the most brilliant writers of our colonial literature, Myriam Harry, devoted several graceful lines to Saigon in one of her evocative novels:

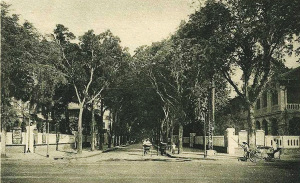

The upper end of rue Catinat

“Ah! what a pretty city Saigon is! We don’t know why we love it, perhaps for its space, perhaps for its somnolence, or perhaps because of its tide of greenery, which swallows up its square white houses with their resemblance to small Greek temples.”

All this is perfectly true; it is certain that Saigon displays an indefinable charm and exercises a strange fascination on all those who visit it, on all those whose hearts it captures, and its evergreen trees certainly play a large part in this. Nevertheless, there is a disturbing question here, because those very trees which line our city streets are currently under threat. The idea of cutting down trees was raised for the first time by a friendly doctor involved in public affairs, who lost something like an arm or a foot or a finger – I don’t know what exactly – and because of this he imagined that he needed to cut down everything around him. He chose the trees of rue Catinat for his first attempt at field surgery, and it is to him, dear reader, that you owe the excessive sunlight which now beats down onto that street near its junction with the rue Lagrandière.

The junction of rue Catinat and rue de Lagrandière

All of our poor trees would have been cut down if this ruthless lumberjack had not fallen victim to the unforgiving climate of our Cochinchina. However, he left behind a legion of devout followers; and, following the example of the empire of Lilliput, where civil war almost broke out between its citizens, Saigon today is still divided between those who advocate an almost complete slaughter of our treelined avenues, and others who argue for simple and hygienic pruning. I agree without hesitation with the latter. In the name of the beauty of the Saigon which we all cherish equally, I say this: cleanse our sewers; make clean water available in abundance; fill that home of microbes, the Boresse Swamp; but please, leave our “Pearl” its green adornment!

A merchant walking along the streets of Saigon in the early 20th century

There are, of course, vandals in all latitudes; and it’s nothing short of a miracle that the giant plane trees and ancient elms which line the incomparable allée des Alyscamps in Arles escaped, most recently, the axes of the tree killers.

Anyway, we will use the cool shade of the trees, which for the moment we are still allowed to enjoy, to wander together through the streets of the city – a city in which for me, every house brings to mind a memory, good or bad, sad or happy. Alas, sometimes those memories are very sad! For it was on the threshold of one of those houses, many years ago, that I left on a journey from which there would be no return. This was the journey I chose as my path through life, one which has left me alone with my infinite despair. Such memories bind one inextricably to the places which evoke them.

And as your “cicerone,” I will try as hard as possible to be the least “Joanne” guide possible [a reference to the Hachette travel guidebooks written by Adolphe Joanne].

The Café de la Terrasse on Theatre Square

First of all, let’s give honour where honour is due. Just as Marseille has its Canebière, so Saigon has its rue Catinat [Đồng Khởi], which it shows off justly and with great pride. It is, indeed, unique.

From the quai Francis Garnier [Tôn Đức Thắng], which by right of occupation would be more accurately be called the quai des Messageries fluviales (River couriers quay), up to the plateau that forms the place de la Cathédrale, lies a route of over a kilometre. Shaded by a double line of tamarind and mango trees, this road rises gently and in recent years the heavy traffic which fills it has made it too small for current needs.

The houses that line the rue Catinat, taken in isolation, have for the most part no special qualities: some are old buildings which date from the time of the conquest, while others are of more recent construction. Most simply have a beautiful appearance and nothing more.

A pousse-pousse makes its way through the tree-lined streets of Saigon

Yet all of them, bathed by the rays of our Cochinchina sun, create an intimate and welcoming cheerfulness, like a group of large family homes which seduce irresistibly. This is true of some women’s faces: itemise their features individually and you will sometimes find them unsightly; but bring them together and they will often form a harmonious whole which charms more than accepted notions of beauty.

The lower part of the rue Catinat, which stretches as far as rue d’Espagne [Lê Thánh Tôn], is occupied by European and Asian traders, while the upper part is reserved for government offices. We will travel quickly from the one section to the other, stopping en route at the exquisite place du Théâtre, which I can describe unreservedly as a real gem.

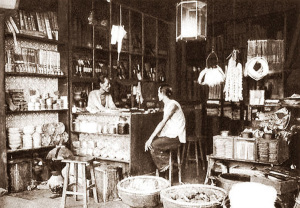

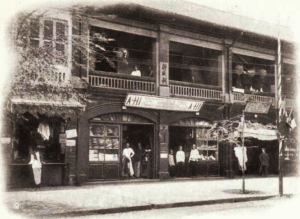

A Chinese shop on rue Catinat

All of the most varied branches of our metropolitan commerce are widely represented on the lower end of rue Catinat: gold and jewelry shops, large, well-stocked bazaars, coquettish millinery shops, comfortable hair salons, bookstores stacked with the latest Parisian novels, pharmacies with gleaming and carefully labelled jars…. nothing is missing, you can buy everything here at moderate prices. But it is undoubtedly the grocery stores which take first place in this animated corner of the city; and this is an area of business in which the good Chinese pose a formidable competition to the French, I must tell you, moreover, that the honourable profession of the grocer is much more complicated here than it is in Europe, as it requires a more complete and varied practical knowledge.

Chinese merchants on rue Catinat

An amiable comic ditty that my good friend S sometimes hums in private, between the pear and cheese, proclaims in its chorus that:

In the business

Of the grocer

It is necessary to sell candles.

However, our Saigon grocers are not content just to add the commerce of the candle to that of selling cans of conserves and other colonial products. They sell a bit of everything, from pith helmets to saddles, manufactured everywhere from Paris to Nuremberg. There’s truly something for everyone.

Grocery stores which have expanded their activities in this way are described generously as “magasins généraux d’alimentation” (general provisions stores); they are more chic and more expensive than the rest.

One of the original Chinese compartment buildings on rue Catinat

Chinese small industry and commerce has effectively taken over the lower end of the rue Catinat, and this deserves our attention.

Here, first of all, picturesquely located in dilapidated old compartments which in this central area form the last vestiges of the old town, one may find a confederation of Chinese tailors whose workshops open directly onto the pavement. Every morning, their brave workers come and sit down, shirtless, in front of the benches upon which their daily work piles up. They don’t leave until nightfall, and it’s wonderful to see their nimble hands stir in a tireless toil, measuring, trimming, cutting and recutting, running their needles through fabric. For them there is no unemployment, no weekly rest, and especially no irritating discussion of the “three-shift” system: only the ritual celebrations of Tết interrupt their ardent working lives for a statutory fortnight’s holiday. And as you may know, it is from such good Chinese manufacturers that come, signed A-Tac or A-Hon, the colonial suits that help us dress so elegantly.

An ice-cream merchant on the streets of Saigon in the early 20th century

The meticulous precision work required by industry of clockmaking and jewelry also naturally appeals to the patient and industrious Chinese artisans, who have also cornered the market in this area. Shops in which rather dated clocks rub shoulders with a whole assortment of native jewelry are also numerous in the rue Catinat.

Further along, furniture makers and basket weavers obligingly spread out their masterpieces of dubious elegance – but beware of termites!

Along the lower end of rue Catinat there have survived a few Chinoiserie and Japonerie merchants which the customs tariffs have not yet reduced to bankruptcy. Once they were many, but now they are a dying breed. I recall many years ago the shop of a very large, paunchy man who combined his official duties as an interpreter in the Immigration Department with a Chinese antiques business. There, by browsing carefully and paying well, one could acquire some very beautiful artefacts.

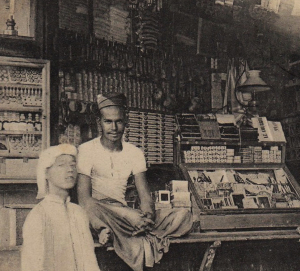

A Chettyar merchant in Saigon

But amongst the hectic scenes of daily life that play out all along rue Catinat, the most interesting are those surrounding the small money changers and tobacconists shops which line the left sidewalk. Around a dozen of these little shops stand side by side, opening directly onto the street. On the threshold of each, set tirelessly in the legendary pose of the artisan at work, stands a son of our French India, boss of his narrow house, proudly exhibiting his wares to passers by, including packs of cigarettes or tobacco of Algerian origin, fine Manila cigars, Japanese matchboxes and wooden pipes. Some of these tobacco shops also have attached to them small haberdasheries selling articles which are specifically intended for military customers.

I have not yet spoken about Saigon’s cafés. So, in order not to give the lie to the reputation of French colonisers, I will say that Saigon certainly has no shortage of them. Many of these, establishments of the second order, are grouped at the bottom end of the old rue Nationale [Hai Bà Trưng] in the neighbourhood of the naval port, which provides them with a guaranteed clientele. But it’s near the theatre that one may find most of the more up-market cafes. These are vast, well-appointed facilities, with large terraces which spill out onto the sidewalk, cluttering them up with a casualness which is very colonial.

The Café of the Grand Hôtel de la Rotonde in the early 20th century

It’s here, at the “green hour,” that the Saigonnais come to rendezvous after the oppressive heat of the day has subsided, escaping from their desks and offices, eager to breathe the “good air” and enjoy the relative cool of the evening. Incidentally, I recall that in one of those vague early accounts of the Far East penned back in the 1870s by one of a special category of travel writer known today as the “pantouflards” (couch potatoes), it was written that Saigon was a city of idlers who spent their days and nights in taverns getting drunk on strong liquor such as absinthe. It’s time to do proper justice to this assessment by describing it as both inaccurate as malicious. They do not drink more in Saigon than they do in France, and consumption of absinthe is certainly more moderate here than it is in other French dependencies. In any case, the harsh climate we experience, ruthless to alcoholics and opium smokers, obviates against excesses of this nature. Let us therefore no longer make such rash judgments. We have a duty to recognise that in a city where one lives mainly an outdoor life, where it is necessary to escape the heat of the office or the solitary home, institutions of this nature have an undeniable practical utility.

André Pancrazi’s Café de la Musique on rue Catinat in the early 20th century

In my case, I can only make a single complaint against the café, and that relates to the incessant noise created by their concert orchestras, which have transformed this exclusive location of Saigon into a true outpost of the Point-du-Jour. You like violins? You’ll find them everywhere on the rue Catinat, from 6pm until curfew, their bows darting back and forth enthusiastically. Where music is concerned, I admit that I’m only a vulgar layman. But for many months in my little hermitage on the rue Blancsubé [Phạm Ngọc Thạch] – a neighbourhood of music lovers – I had to suffer the piano playing of a very amiable boy who sat down at his piano in the late morning and didn’t get up from it until nightfall. He carried on playing endless scales on this horrible instrument, interrupted only by his appalling rendition of “Salut, demeure, chaste et pure” from Gounod’s Faust. His dragging interpretation of the high note which marks the penultimate syllable of this air left a throbbing and painful impression in my eardrums which still lingers today. It almost drove me mad, and had it done so, that would have been very unfortunate for my family.

So let’s waste no more time being grumpy about the cafés of the rue Catinat with their blaring music and continue to the place du Théâtre.

To read part 2 of this serialization, click here

To read part 3 of this serialization, click here

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.