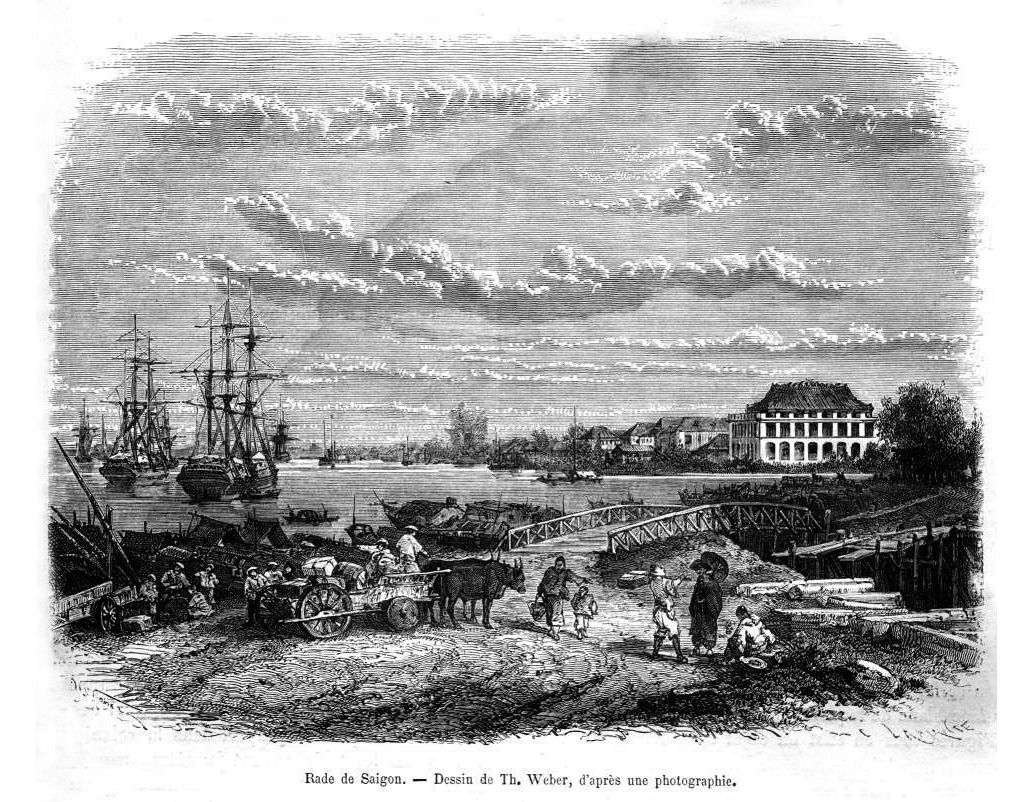

The Rade de Saigon, engraving by Th Weber taken from a photograph

Voyage en Cochinchine, an account of naturalist Dr Albert Morice’s 1872 visit to Saigon, Chọ Lớn and the Mekong Delta, was first published in the geographical adventure magazine Tour du Monde. This is the first of two extracts, translated into English.

It was 9.30am on 6 July 1872 when the propellers of the La Creuse stopped and we cast anchor in the Saigon harbour. Our huge steam ship was immediately surrounded by sampans, small Annamite [Vietnamese] boats that bring to mind the gondolas of Venice. Almost immediately, a crowd of officers and traders flooded the decks. Knowing that there would be no friendly face looking for me, I contemplated the landscape until it was time to go ashore.

Awaiting the disembarkation of passengers at Saigon port

The sky was full of huge copper-edged clouds, between which passed the scorching rays of a sun even more implacable than that which I had experienced in Singapore; the river at this point was so broad that it well deserved the name of “rade” which we had given it. A crowd of boats of all kinds – rowing, sailing and steaming – crowded all around us; they included a number of merchant vessels and two English steamships. In the distance, I could see the Fleurus, a stationary vessel from which the daily gun shots announcing the beginning, middle and end of the day were fired.

The right bank of the river was covered with very small mud and straw huts, most of which dipped halfway into the Donaï river, while on the left bank was the city of Saigon (not Saïgon, as we still insist on calling it in France). The great Hôtel Cosmopolitan or Maison Wangtaï, with its wide three-storey façade, stood proudly on the edge of the dock; beyond it, the regularly-spaced tamarinds of rue Catinat and other arteries of the city raised their large, verdant canopies; and the numerous but uncomfortable carriages known as Malabars waited for the multiple prey that would be delivered to them.

At about 11am, leaving my luggage to be carried along with that of French government passengers to the Naval wharf, I disembarked from the ship and my feet finally touched the dusty red earth of Saigon.

Colons wearing the salaco

Although new to the colony, I had gathered enough information to know that I should first visit one of the countless Asian merchants whose stalls line the lower streets of the city, in order to purchase a salaco. The salaco is the hat of the tropics; it shares with the pith helmet (known by the English in India as the sola topee) the function of protecting the skulls of Europeans from the over-ardent kisses of the sun. It’s true that it’s unsightly and rather heavy, but one adapts quickly enough to this strange headgear, the white dome of which prevents sunstroke. An honourable Chinese merchant who answered to the harmonious name of Atak soon found me what I needed, after which I hurried into the first hotel that I encountered on my journey.

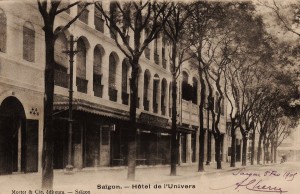

The name of this caravanserai – “Hôtel de l’Univers” – was proudly displayed above a bright and clean verandah. I entered a room occupied by several Europeans which served as a café. Having already lunched on board, and also being quite tired, I thought only about taking a bath and having a rest: a bedroom was granted to me, with a spacious mosquito net, but alas, the net was riddled with holes! Nonetheless, after a sea voyage of 45 days, it was good finally to rest my sore limbs on land.

I woke up at about 3pm, and after taking a shower, I went to get my luggage. Two large Chinese porters, naked to the waist, wearing tall, thick straw hats and carrying on their shoulders a traditional solid bamboo pole, rushed after me and seized my cases with great speed – not without some shouting in their monosyllabic language which at first sounds displeasing to European ears.

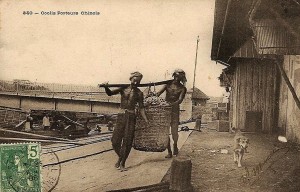

Chinese porters

Tying the packages to the centre of their long pole and then placing the cases at each end, they lifted them onto their reddened shoulders and resumed their march with a characteristically swinging gait.

This important matter resolved, I made my way down to the dining room. At first, all I saw was a number of small tables, and above them two parallel rows of punkah fans. The punkah, which comprises cotton sheets affixed to both sides of a square wooden frame, is held by a rope that passes through a pulley and then through a hole in the wall to the next room. There, a servant pulls on the rope in order to move the punkah back and forward. It’s thanks to this invention (which comes, I think, from India) that in the evenings one can withstand the general weakness and reluctance to eat which one almost always experiences after a scorching day in this climate. The air current produced by the punkah not only revives the strength and the appetite, but also scatters mosquitoes and other annoying insects that seek your skin… or your soup.

After an abundant meal (a long passage on board ship usually involves frugal eating), I went outside to one of the small tables where coffee and liqueurs were being served, and there I began to examine my new environment more closely. Once more, I noticed something which had struck me when we first arrived – the unique appearance of the colonial inhabitants, in particular those who had lived in the colony for some time: they all had an emaciated figure and a slightly yellowish complexion.

The Hôtel de l’Univers

During my meal, I had also noticed that the conversation around me gathered pace and intensity as my fellow diners worked their way through their courses, and that by the time they reached dessert, the diners at some tables were engaged in open dispute with each other. Perhaps soon, my face will also assume this colonial “livery” and, like it or not, I will become more easily irritated.

I spent the remainder of the evening with Mr L, whom I had met during the sea voyage and who was the most jovial individual I had met on my journey. He was also staying at the Hôtel de l’Univers, but had not dined there. He took me to one of the many cafés that lined the wharf, and we drank to our happy stay with a bottle of Norwegian pale ale.

As soon as we began to roll our cigarettes, some small Annamite children approached us and offer us a light. This disguised begging, perhaps the only type which one encounters in Cochinchina, was accomplished with such pleasant gestures and laughter that I neglected to use the little brazier which had been brought to the table for the use of smokers.

The next morning, awaking from a sleep which had been disturbed by too many bloodsucking insects, I decided that my mosquito net should be given the only definition that suited it: a muslin mosquito trap. I got up and resolved to visit the city. But before meeting my natural curiosity, I wanted to check on the health of some creatures I had brought with me from France, and on which I had devoted much paternal care during the long voyage.

Vietnamese children in Saigon, late 19th century

These were two vipers, still young, but whose emerging graces delighted me. I open the dresser where I had placed the box containing the creatures. Horror! Legions of black ants escaped from it, leaving only two very well cleaned snake skeletons. The tropical ant had just revealed to me all of its feverish activity. I will not dwell on my deep pain: you must have a heart of naturalist to understand it.

Still grieving over this sad affair, I left the hotel and went out onto the street, leaving my friend who was still asleep in his room. In fact, when I visit a city for the first time, I prefer to do so alone; it seems to me that in this way, impressions are engraved upon one’s mind in a more lasting manner.

As I made my way outside, the hotel’s honourable “con chó,” an ugly little pug, greeted me with contemptuous barking. I turned right onto rue Catinat [Đồng Khởi street], one of the main arteries of the city. It was about 6.30am, and the Chinese who inhabit the lower parts of the street had already commenced their morning ablutions outside their front doors, with the total lack of embarrassment and shame that characterise this race. Carriages driven by black Malabar Hindus began chasing me with shouts of: “Voiture, capitaine, voiture!” And as soon as I stopped at a stall, a group of ugly little men with uncultivated hair, wearing an old marine infantry soldier’s hats and very brief costumes, gathered around me with their vast baskets of goods and assailed me with the cry: “Capitaine, panier, hein!”

As I walked further away from the river, the street gradually ascended towards the plateau and its European-style buildings increased in number. Towards the top of rue Catinat, I saw on my left the charming little palace of the Director of the Interior, located in the middle of a verdant green area where a large deer suddenly raised his head and looked at me curiously.

Cochinchine – Trésor publique de Saigon

Further along, I saw the offices of the government, the Treasury and the Post Office. It is true that at present these buildings are still mostly separated from each other by empty lots, large or small, where bamboo, castor, datura (jimsonweed), large vines and tall grasses grow at will. But as the main city artery, the rue Catinat is bold and well-designed, and its delightful buildings create a very good impression.

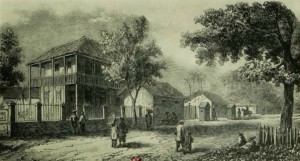

By about 8am, despite my salaco, the heat from the sun had become unbearable, and I began to retrace my steps back the hotel, this time taking the rue Nationale [Hai Bà Trưng street], a street parallel to the rue Catinat and less inhabited. The street contained a mixture of both comfortable houses and tiny bush huts. Along the way, I passed the old Governor’s Palace buildings, the Office of the Director of Health and the Naval Engineering Department.

As I walked, I encountered a number of Hindu men and especially women, with their black or copper-coloured skin, silver nose rings and glittering costumes in bold primary colours such as yellow or green. Their majestic plumpness contrasted strongly with the small frame of the Annamite women, bent under the weight of the goods they carried to the market. The latter were followed by their children, also charged with disproportionately large burdens that forced them to rest frequently.

The first Governor’s Palace

Reaching the middle of the street, I saw on the right a police station, out of which came several Europeans, Malabars, Chinese, and above all, Annamites dressed in police uniforms with small swords, tiny salacos and big buns on the sides of their heads. Occasionally my path was crossed by rich Chinese, followed by young Annamite porters carrying provisions.

I went back to the hotel very happy with my first exploration, which had allowed me to take a look at the different races that inhabit the city, as well as the exuberant products of nature to which the rays of the sun and water of the sky are so generous.

But I must immediately say a word about the suffering which every European should expect in Saigon. Already, when visiting the Red Sea, I became acquainted with one of the worst enemies of people of our race in the tropics: the eruption of itchy papules commonly known as prickly heat (Lichen tropicus).

Your whole body, or most of it, is covered with small blisters as big as a pinheads, and the itching is so irresistible that it takes heroic courage to resist the desire to burst thousands of them every day. It is especially during the dry season that this cruel eruption afflicts newcomers, and even the “vieux Cochinchinois,” as those who have several years of experience in the colony are known. The refreshing rains of winter moderate or remove these papules. Indigenous people seem to be exempt from this infirmity, but for Europeans, almost nothing can be done to treat it, and where the skin is thin and delicate, the papules can be very unsightly.

To read Part 2 of this serialisation click here

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.