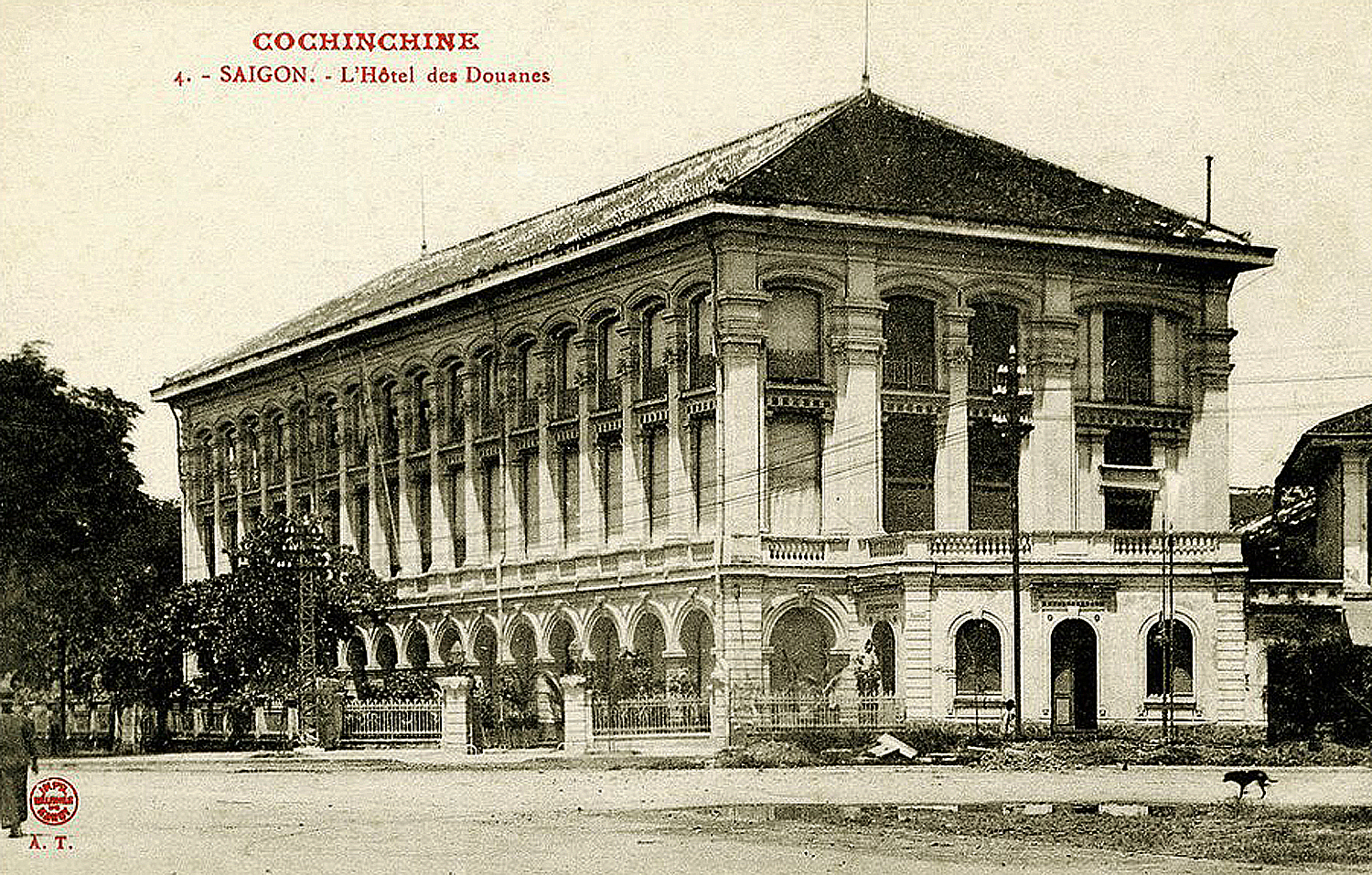

The Hôtel des douanes in the early 1900s

This article was published previously in Saigoneer.

The Customs Directorate, one of the city’s best-loved colonial landmarks, is the latest in a series of government buildings to face the threat of redevelopment.

The facade of the Customs Directorate building today

According to a reliable source, the Hồ Chí Minh City Customs and Excise Department is currently seeking permission to demolish and rebuild its headquarters, the former Hôtel des douanes (Customs Directorate) at 21 Tôn Đức Thắng, which was built in 1885-1887 to a design by celebrated French architect Alfred Foulhoux. Like most of the city’s colonial buildings, the Customs Directorate building is not recognised as built heritage, and thus enjoys no legal protection.

The Customs Directorate building is in fact the second major civic building to be constructed on this site. Its forerunner was the grand three-storey brick residence of wealthy Cantonese merchant trader Wang Tai, who ran the Cochinchina opium monopoly between 1861 and 1881.

The Maison Wang-Tai in the 1870s

Inaugurated in 1867, and known popularly as the Maison Wang-Tai or Hôtel Wang-Tai, this building is said to have caused some embarrassment in the upper echelons of the colonial administration, because it was far grander than the first Admiral-Governor’s Palace – a series of three wooden buildings imported in kit form from Singapore!

Many of the rooms in the Maison Wang-Tai were rented out to tenants; most notable among the latter was the first Mairie (Town Hall), which in 1869 occupied a whole floor. Wang Tai later relocated all of his operations to Chợ Lớn, permitting the conversion of his building in 1874 into the Hôtel Cosmopolitan. Perhaps as a consequence, the alley behind it, known throughout the colonial period as the rue des Fleurs, subsequently became home to a large number of “houses of ill-repute.”

The Maison Wang-Tai in 1882 after it was converted into the headquarters of the Directorate of Customs and Excise

In 1881, the French authorities moved to break Wang Tai’s monopoly in the shipping and processing of opium. Then, in the following year, they purchased the Maison Wang-Tai outright for the sum of 200,000 Francs, and transformed it into the headquarters of their Directorate of Customs and Excise (Direction des Douanes et Régies) – ironically, the very same government agency which controlled the lucrative opium franchise.

However, they quickly found that the old building was not as capacious as they had envisaged. Surviving pictures of the original Maison Wang-Tai show that interior space was sacrificed to create wide open corridors behind the facade on all three floors. The Directorate of Customs and Excise needed more room, and accordingly in 1885, Cochinchina’s Chief Architect Marie-Alfred Foulhoux (1840-1892) was commissioned to rebuild the Maison Wang-Tai as the Hôtel des douanes – the building which stands today.

A side view of the Hôtel des douanes in the early 1900s

Foulhoux’s brief was simply to rebuild the earlier edifice in a way which made optimal use of space, and his design retained the floors and several walls of the original Maison Wang-Tai. Despite this, he succeeded in creating one of the city’s most attractive pieces of neo-classical architecture, grand in proportions and elegant in detail.

Of particular interest to many tourists is the decoration on the upper facade of the building. Writer, journalist and Indochina specialist Jules Boissière (1863-1897) pointed out that the badges between the third-floor windows feature opium poppies, by the 1880s one of the most important revenue streams for the Cochinchina government!

The opium poppy decoration on the upper facade of the Customs Directorate building today

Foulhoux’s Hôtel des douanes still functions today as a Customs Department, nearly 130 years after it was built. News of its threatened demise has been greeted with disbelief by conservationists, many of whom have voiced concern that such a major architectural work has not yet been recognised as heritage, and can apparently be destroyed at the whim of its occupants.

UPDATE: It is now reported that this building will not after all be demolished, although there are rumours that a new tower block may be constructed immediately behind it.

For information about other heritage buildings under threat of demolition, see also:

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Ba Son Shipyard, 1790

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Former Cercle des Officiers, 47 Le Duan, 1876

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Former Secretariat du Gouvernement Building, 59-61 Ly Tu Trong, 1888

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Vietnam Railways Building, 136 Ham Nghi, 1914

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Former Imprimerie de l’Union Building, 49-57 Nguyen Du, c 1920

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Saigon Tax Trade Centre, 1924

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Former College de Can-Tho, 1924

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Catinat Building, 26 Ly Tu Trong, 1927

Date with the Wrecking Ball – 213 Dong Khoi, 1930

Date with the Wrecking Ball – 606 Tran Hung Dao, 1932

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Former Maison du Combattant, 23 Le Duan, 1932

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Former Bot Catinat, 164 Dong Khoi, 1933

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Saigon Hospital, 125 Le Loi, Late 1930s

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.