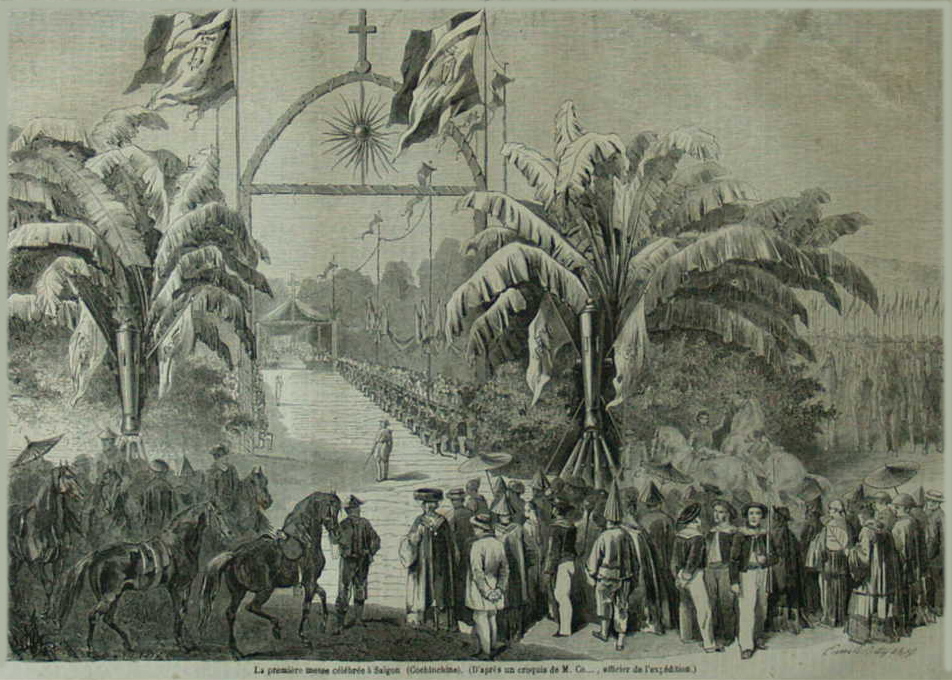

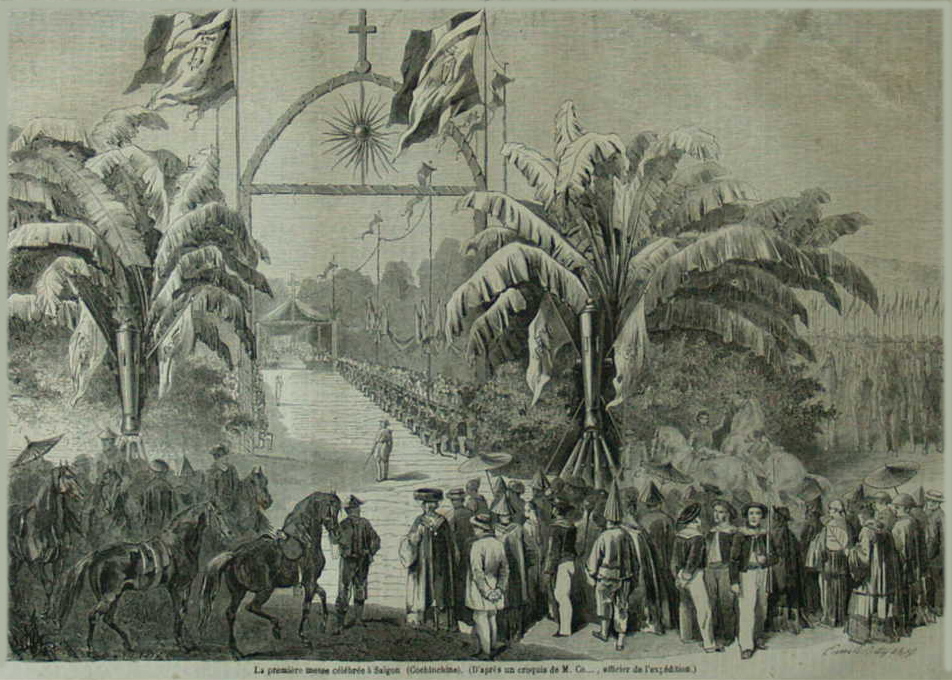

La première messe célébrée à Saigon (Cochinchine) – The first mass celebrated in Saigon – 1861

This unpublished document, housed in the library of the Archdiocese of Saigon, describes the early years of Saigon Parish.

1. Historic memories of the city of Saigon

The origins of the city of Saigon are rather uncertain. It appears that, before the time of Gia-Long, it was a simple Cambodian village. In 1680, however, it was for a certain time the residence of the second king of Cambodia.

In 1789, Gia-Long, after taking Saigon from the Tay-Son, commissioned the construction of the first Citadel, which was enclosed by the rue Testard [Võ Văn Tần] in the north, rue Mac-Mahon [Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa] in the west, boulevard de la Citadelle [Đinh Tiên Hoàng] in the east and rue d’Espagne [Lê Thánh Tôn] in the south. The centre, where the mast of the pavilion stood, was approximately at the site of the present Cathedral.

The city of Saigon was occupied by Gia Long for 22 years.

Marshal Lê Văn Duyệt

After his return from France, Monsignor Pigneau de Behaine, Bishop of Adran, lived in Saigon, in a house which Gia-Long had built for him at the outer corner of the Citadel, close to the site of the former maintenance shop in the nursery of the Botanic Garden, now the barracks of the indigenous militia. He accompanied Prince Canh to the siege of Qui-Nhon, where he died on 9 September 1799, at the age of 58 years. His remains were brought back to Saigon on the 16 September, and on the 16 December his funeral was solemnly held at the Tomb of Adran.

From 1811-1831, Gia-Long having established his residence in Hue, Viceroy Le-Van-Duyet peacefully ruled Lower Cochinchina until the year of his death. He was feared by Minh-Mang, who dared not undertake anything against him. The importance of his services and the authority he had managed to acquire made him almost invincible. Here is a fact which shows his good disposition. Once, when attending a cock fight in 1828, he was told of the first edict of persecution launched by Minh-Mang against the Catholic religion and the Europeans in general. “Why are we persecuting the co-religionists of the Bishop of Adran and those Frenchmen whose rice we still grind between our teeth?” He exclaimed. “No, as long as I live, we will not permit that. Let the king do what he pleases after my death.” His tomb, desecrated first by Minh-Mang, then repaired and maintained by the French administration, is located opposite the Inspection de Gia- Dinh.

After the death of Viceroy Le-Van-Duyet, Saigon fell into the hands of Nguyen-Van-Khoi, who revolted against the king. Minh-Mang retook Saigon in 1834. The sons of Khoi, the rebellious mandarins, and a French missionary, the Blessed Father Marchand, detained in the midst of the siege, were caged and taken to Hue for death. Minh-Mang then destroyed the Citadel raised by Gia-Long, and replaced it by a work of lesser extent, which was taken by the French in 1859. On the same site today stands the new Marine Infantry Barracks.

2. Beginnings of Saigon Parish after the occupation of the city by the French

The martyrdom of Saint Paul Lê Văn Lộc (1830-1859), unknown artist

On 11 February 1859, Admiral Rigault de Genouilly forced his way into Cap Saint-Jacques, and sailed up the Saigon River to seize the city. At that time in the prison of Saigon was a young Annamite priest named Paul Loc. The king’s judges, hearing of the arrival of the French, unexpectedly led him out to be executed. He was decapitated near the gates of the Citadel, at the corner of rue Paul Blanchy (formerly rue Nationale) and rue Chasseloup-Laubat. He was canonised by Pope Pius X on 2 May 1909.

At the time of the arrival of the French, a price had been placed on the head of the Vicar Apostolic, Monsignor Dominique Lefèbvre. However, he was able to escape, and on 15 February 1859, he boarded a French ship, where he was received with due regard for his dignity and person.

Finally, on 18 February 1859, Saigon belonged to France.

After the capture of Saigon, many Christians, fleeing persecution, came from everywhere to take refuge under the French cannon. This explains the presence today of so many Christians in the neighbourhood of Saigon. However, at that time, the parish of Saigon as a separate Christian community did not yet exist; Monsignor Lefèbvre spent much of his time founding it. In order to establish Christianity more firmly in the centre of his diocese, and to make it radiate outwards into other neighborhoods, he began by establishing major institutions and furnishing himself with devoted auxiliaries.

Seminary

The first of the major institutions set up by Monsignor Lefèbvre in date and importance was the Seminary. Initially established in the swampy and tiger-infested area of Thi-Nghe, in the vicinity of the Annamite soldiers’ post, the Seminary was transferred to Xom-Chieu in 1860. But a few months later, the Mission obtained a large plot of land on the Boulevard Luro, and Monsignor Lefèbvre definitively installed the Seminary there, entrusting it to the care of M. Theodore Wibaux.

The Seminary in 1866

The latter constructed a large building which lasted for about 13 years. After that, it was necessary to rebuild the Seminary almost entirely. The new buildings, which still exist today, were thanks mainly to the intelligence and devotion of Messrs Julien Thiriet, second superior of the Seminary since 1877, Félix Humbert and Charles Boutier. In 1887, Monseigneur Colombert solemnly inaugurated the most important building, which occupies the central position. Thereafter, the two wings were added, both designed by Father Humbert, one destined for the students of the grand seminaire, and the other for the students of the petit seminaire.

At present, the total number of seminarists is 129, a figure made up of 26 in the grand seminaire and 103 in the petit seminaire.

Sisters of Saint-Paul de Chartres

Having assured the recruitment of the clergy by founding the seminary, Monseignor Lefèbvre provided for other needs by calling on the Sisters of Saint-Paul de Chartres, who arrived at Saigon in 1860. They were first charged with gathering the orphans created every day by the persecution, and the numerous pagan children abandoned by their parents, who wandered the streets of the city in rags, begging for food. This was the first nucleus of the work of the Sainte-Enfance (Holy Childhood) orphanage in Saigon.

The first building constructed for the Sisters of Saint-Paul de Chartres

This work began very modestly in a large and rather unsuitable hut, located near the primitive first bishop’s palace, near the site of the old market. Two years later, Admiral-Governor Bonard gave to the Reverend Mother Benjamin, Mother Superior of the Sisters, another vast site on the Boulevard Luro, occupying the space between the Arsenal and the Seminary.

The establishment of the Sisters of Saint-Paul today consists of: (i) a Novitiate for the training of indigenous Sisters; (ii) a boarding school for European and mixed race girls; (iii) another boarding school for Annamite girls belonging to the rich families of the Colony; (iv) an orphanage for abandoned children; and (v) a refuge for poor Annamite girls who had been seduced and desired to rehabilitate themselves in their own eyes and in the eyes of others.

Indigenous Hospital

Monseignor Lefèbvre also created, for the benefit of sick and destitute indigenous people, a hospital, whose administration he entrusted to the Sisters of Saint-Paul. This hospital, located initially near the first bishop’s palace, was relocated in September 1864 to the north bank of the arroyo Chinois in Cho-Quan, by mutual agreement between the Mission and the government. Since 1909, the Sisters have been relieved of their duties at this hospital, but they do not cease to give their care to a very large number of patients in their own hospital in Thi-Nghe, which was built for this purpose 300 meters from the church in the parish of the same name. They thus continue the work begun by Monsignor Lefèbvre.

Carmel

The Carmelite Convent

It is not enough to work for the salvation of souls. In the supernatural order, human efforts may end in no result if God does not support and nurture works with his grace. It was in order to secure perpetual prayer and to draw the blessings of Heaven upon his work and that of his auxiliaries, that Monsignor Levèbvre invited the Carmelite Order of Saint Therèse to Saigon. The first four Carmelites arrived in Saigon on 9 October 1861. They were welcomed by the Sisters of Saint-Paul, and settled soon after near the Seminary, on elevated ground on the other side of boulevard Luro. Their pious community has always prospered, and for a long time it has had around 40 Sisters, including 4 Europeans and 36 Annamites.

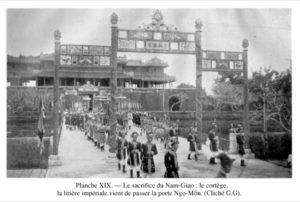

While Monsignor Lefèbvre worked to make Saigon a Christian town, the Admirals continued the conquest. On 1 November 1859, Admiral Rigault de Genouilly was replaced by Admiral Page. The expedition was continued in 1860 by Rear-Admiral Charner, and in 1861 by Rear-Admiral Bonard. On 5 June 1862, when the Treaty of Peace between Emperor Tu-Duc and France was signed in Saigon, the religious question was regulated in accordance with the principles of Admiral Bonard by Article 2: “The subjects of the two nations of France and Spain may practice their Christian beliefs in the kingdom of Annam; and the subjects of this kingdom, without distinction, who would desire to embrace and follow the Christian religion, may do so freely without constraint. But those who do not desire to become Christians will not be forced to do so.”

This treaty put an end to open persecution; but the arbitrary advances and vexations against the Christians continued almost as in the past, especially in Annam. Meanwhile, the Christians in Saigon and neighbouring provinces, being closer to the French, lived in greater tranquility.

Admiral Pierre-Paul de La Grandière by Mascré-Souville, Musée du quai Branly

Admiral de la Grandière, who replaced Rear-Admiral Bonard in May 1863, understood that the assimilation of the natives in Cochin-China could only be achieved through Christianity, and that the Christian element, the fidelity of which could not be questioned, was entitled to be treated with more consideration. His solicitude for the religious interests of the colony was manifested by the measures he took to protect the good Sisters and by the example of his irreproachable conduct.

3. Definitive foundation of the parish of Saigon and its development to the present day

Until the year 1863, the Missionaries residing at the Seminary or in the neighbouring Christian communities served the city’s religious and administrative communities with the Holy Sacraments. The time had come to found a separate parish, which would include the agglomeration of these various communities and all the Christians, French and Annamite, living in the city. This is what Monseignor Lefèbvre did, by appointing M Oscar d’Amplemann de Noioberne as parish priest of Saigon, and by fixing the parish limits, which have remained almost the same since its date of foundation.

Scope and limits of Saigon parish

The parish of Saigon is bounded to the north-west by the rue Richaud, which separates it from the parish of Tan-Dinh; to the north by the arroyo de l’Avalanche, which separates it from the parish of Thi-Nghe; to the east by the Saigon River, which separates it from the parish of Thu-Thiem; to the south by the arroyo Chinois, which separates it from the parish of Khanh-Hoi; and to the south-west by the rues MacMahon, Filippini, Taberd, de la Pepiniere, Chasseloup-Laubat and Lareyniere (up to rue Richaud), which separate it from the parish of Cho-Dui.

Since the construction of the new City Market in 1914 and the new Railway Station in 1915, the populous centre of the Annamite city has been moved, and the Christians who live on the streets below the station are now obliged to make a long detour in order to reach Cho-Dui Church.

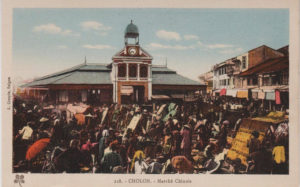

Saigon, 1920

It thus follows that, whatever one may do and say, almost all Christians from that area now find it easier to come to the Cathedral for worship and for reception of the Sacraments. It would therefore be desirable that, for the greater good of souls, the limits of the parish of Saigon near Cho-Dui should be moved back as far as the rue Bourdais. In this way, the parish of Saigon would encompass the Market, which would fall under her by force of circumstances, and would be separated in a straight line running south from the parish of Cho-Dui along rue Lareyniere and rue Bourdais, cutting through the middle of the Jardin de la Ville.

By 1863, Monseignor Lefèbvre had successfully completed all his undertakings; He had gathered under the parish the various new elements (communities, French, Annamites) in the city of Saigon. In the following year, 1864, the Apostolic Vicar, feeling his strength to be diminishing, asked the Holy See to be released from his office. He ceded the government of the Mission to Monsignor Miche, the first Apostolic Vicar of Cambodia since 1852. When the new bishop arrived in Saigon, Admiral de la Grandière gave him a triumphal reception, which produced the strongest impression on the Annamite population.

A few months later, on June 1865, another religious event came to rejoice and comfort the Christians of the city and its environs in their faith. For the first time, the Fête-Dieu was publicly celebrated in Saigon; and the God of the Eucharist was carried in triumph through the same streets and public squares where Christian blood had once flowed. An immense population, hastening from afar, came to contemplate this extraordinary spectacle. The communities of all the neighbouring parishes, preceded by their banners, together with the orphans of the Sainte-Enfance, the Christian Brothers, the Sisters and the Schools formed a cortege of Jesus the Saviour, which thus took official possession of the capital and of the whole colony.

La première messe célébrée à Saigon (Cochinchine) – The first mass celebrated in Saigon – 1861

Twenty missionaries preceded the canopy, under which the Apostolic Vicar elevated the sacramental Host. It was escorted respectfully by a large number of soldiers and officers, the Admiral Governor at their head. When they arrived on the quayside opposite the ships, the Holy Sacrament was deposited on a magnificent altar made by the sailors themselves, and then the blessing descended upon this immense multitude, while a salvo of 21 cannon shots announced in the distance the triumph of Christ, the splendours of his religion, and the faith of his worshippers.

This imposing religious manifestation, which had the advantage of recalling to our compatriots the memories of their absent homeland, and of giving to the natives, both pagans and Christians, a high idea of Catholicism and of France, was repeated every year down to 1881. At that time, for reasons of neutrality and freedom of conscience, our troops were no longer authorised to take part officially in such ceremonies, so the episcopal authority thought it necessary to suppress this procession, which could no longer be carried out with the same grandeur and solemnity. But the government never banned it. To this day, the parishes around Saigon, Tan-Dinh, Cho-Quan, etc, continue this old tradition every year in their own communities. The Christians always display great zeal in adorning the streets, and flock in crowds to accompany the Most Holy Sacrament, which is carried through their villages.

By all that we have just said, it is easy to see that Admiral de la Grandière really had at heart the development of Catholicism in the colony. He proved this by bringing the Brothers of the Christian Schools to Saigon. Six of them arrived on 6 January 1866, the Mission having given them the Collège d’Adran, which had been founded two years earlier by M. Puginier. They immediately set to work, devoting themselves to the education of youth until the end of 1882, when they were obliged to retire.

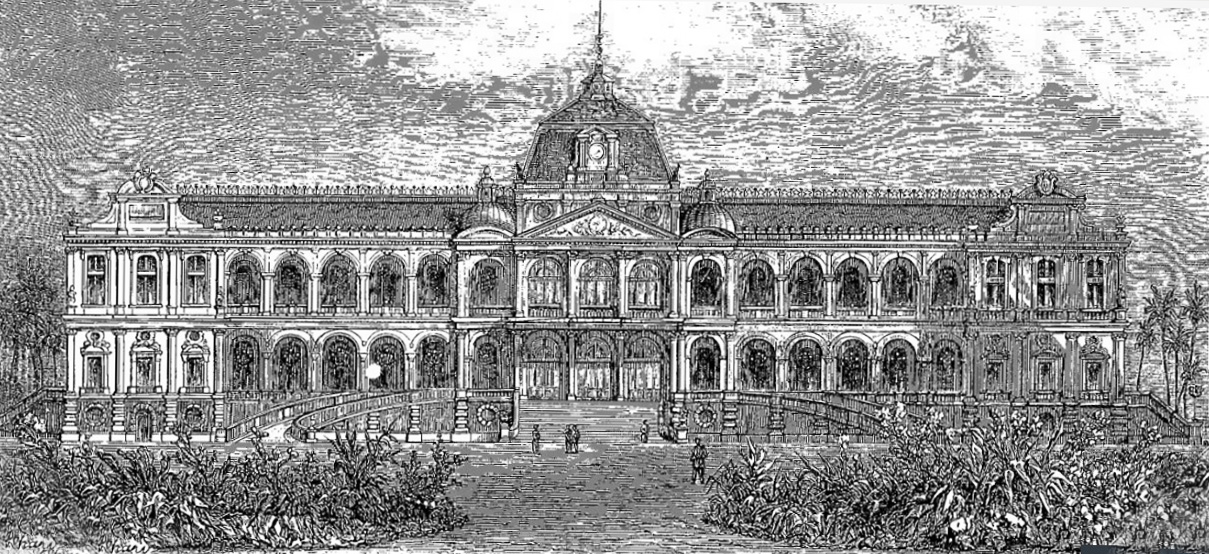

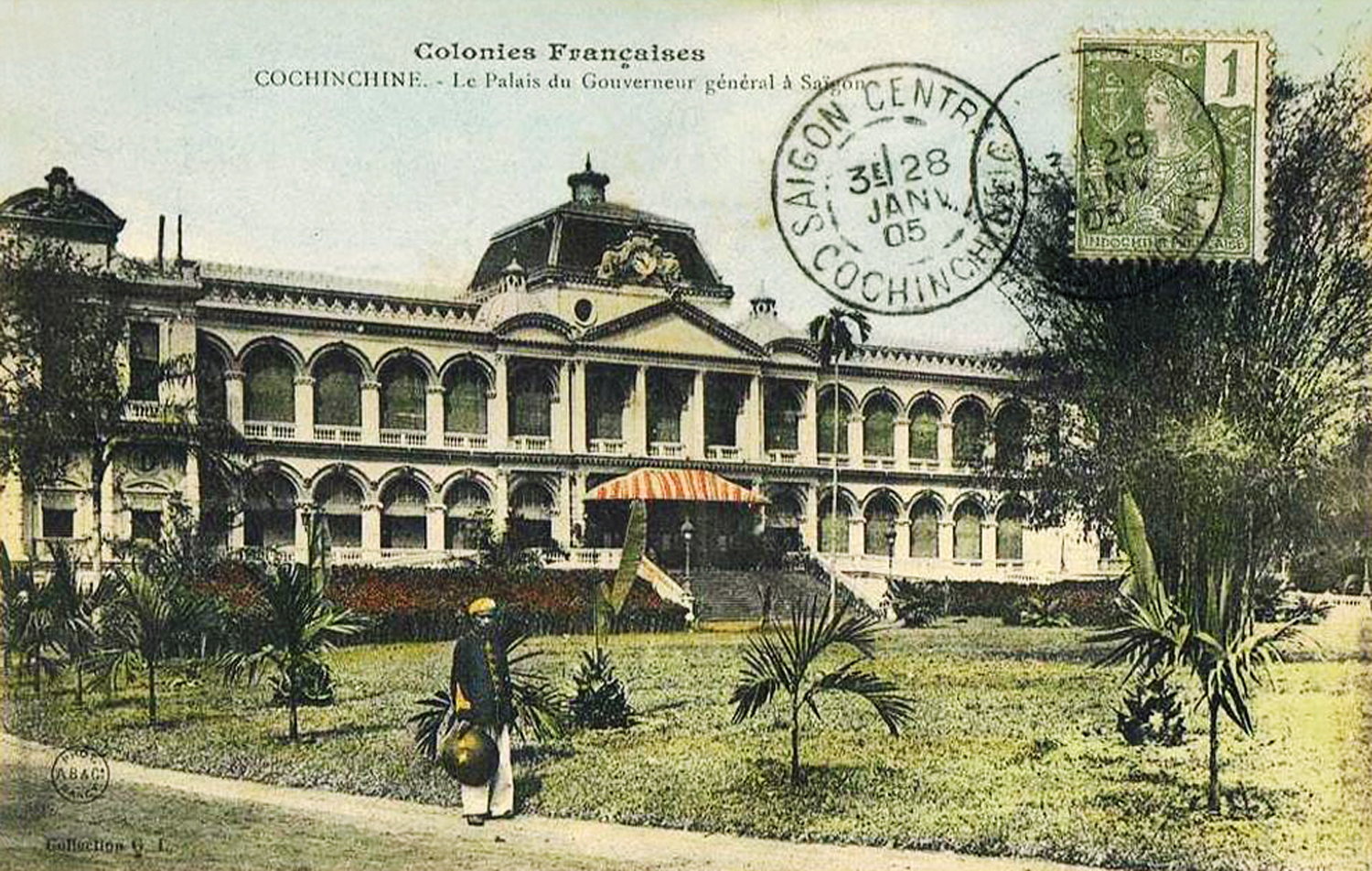

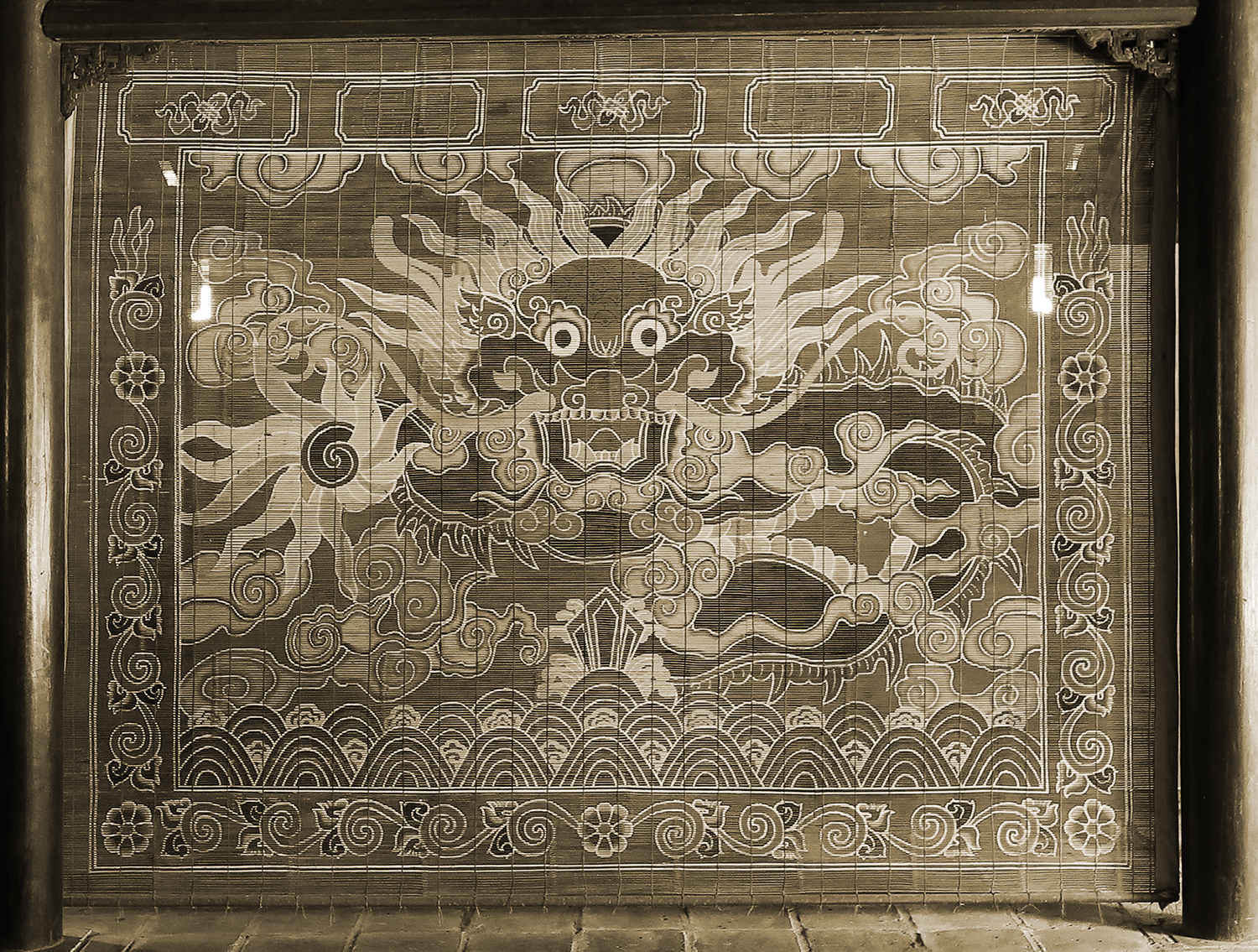

“La première résidence des Gouverneurs à Saigon” – the Salle de spectacles or events hall of the first governor’s palace, from the 1931 book Iconographie historique de l’Indochine française (1931) by Paul Boudet and André Masson

The work they had begun was seconded at first, then continued by the Collège Taberd; But in the meantime, several changes had taken place in the Christian community of Saigon. Monseigneur Miche died in 1873, and was replaced by Monseignor Colombert. On my side, M. Oscar de Noioberne, the first parish priest of Saigon, left office, and ceded his post to M. Henri de Kerlan. It was Henri de Kerlan who, in 1874, at the same time as the Cathedral was transferred from the lower town into the salle de fêtes of the old Palace of the Government, founded the École Taberd in its old outbuildings.

At this time, the present location of the Institution Taberd housed the temporary Cathedral, the Presbytery and the School.

Directed initially by the Missionaries, the École Taberd was, in 1889, entrusted to the Brothers of the Christian Schools, who had been invited here by Monseignor Colombert. Tody this College teaches more than 800 pupils, both Christian and pagan, European, mixed race, Annamite, Indian and Chinese. It is located at the corner of rue Paul Blanchy and rue Taberd. Its buildings, large and well furnished, were built largely by Monsignor Mossard, now Apostolic Vicar, and completed by the Christian Brothers. They are the property of the Mission.

M Henri de Kerlan died in 1877, and was replaced by Henri Le Mée, who remained priest of Saigon parish until 1897. In the year of his installation he had the joy of seeing the construction of the new Cathedral, and next to it a beautiful Presbytery, which is still in use today.

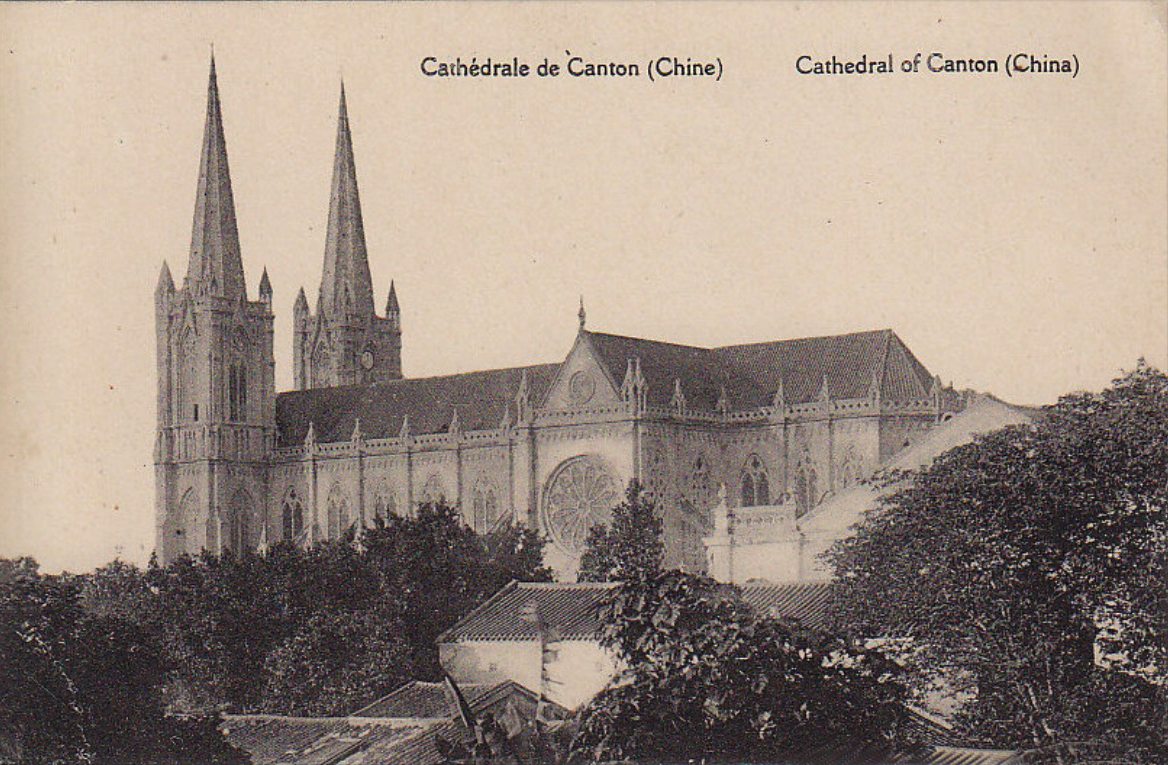

Cathedral

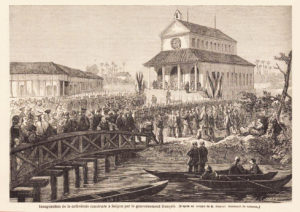

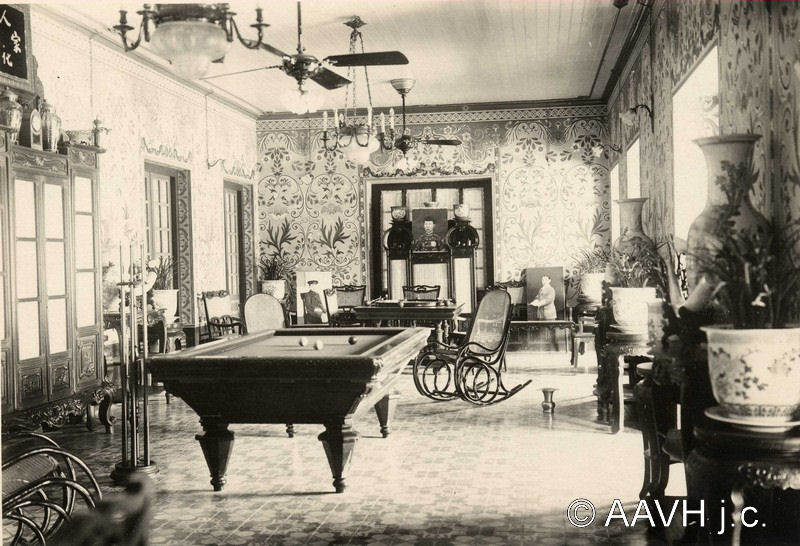

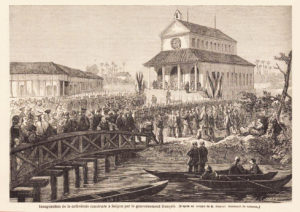

Inauguration of the (first) cathedral constructed in Saigon by the French government in 1863 (after a sketch by Naval Lieutenant Dumont)

First among all the religious edifices of the colony is, of right, the Cathedral of Saigon. Yet it was not always so. At the beginning, Monseignor Lefèbvre converted an abandoned pagoda into a church. Then in 1863, Admiral Bonard had a more suitable church built in the lower town, on the site now occupied by the Justice of Peace. But, after 10 years, this edifice, built almost entirely of wood, was devoured by white ants. In 1874, it was necessary to set up a temporary church in the salle des fêtes of the former Governor’s Palace, on the site where the Collège Taberd now stands. Clearly this provisional measure could not be permitted to continue indefinitely. Admiral Dupré (1874-1877) had the merit of understanding that France, now firmly established in Saigon, had to assert its faith and consecrate its conquest in this distant country, by elevating to God a definitive temple, more worthy of His Supreme Majesty.

On 7 October, 1877, Monsignor Colombert, in the presence of the Governor and all the authorities of Saigon, blessed the first stone of this sacred edifice, which was to be constructed in an excellent position at the top of the rue Catinat, the highest point in the city. The work was carried out so rapidly that the blessing of the church could be achieved after just two and a half years, on 11 April 1880. It was dedicated to the Immaculate Conception and to St Francis Xavier.

The Cathedral of Saigon is a Romanesque style building which measures 93 metres from the front porch to the extremity of the apse; The width of the transept is 35 metres, and the towers rise 36.6 meters from the ground and house six bells, together weighing 25.85 tonnes. Two spires of 21 metres, completed in 1895, take the height of the Cathedral to 57 metres total. The interior of the building is adorned with sobriety and good taste. At the top of the triforium, a series of stained glass windows depict a procession of the Saints of the Old and New Testaments, who pay homage to the Immaculate Virgin, patroness of the Cathedral, whose image is located in the apse of the church.

The (second) Saigon Cathedral pictured soon after its inauguration in 1880

The high altar, made from precious marble, is adorned with three magnificent bas-reliefs, and supported by six angels carrying the Instruments of the Passion. On either side is a monumental Way of the Cross, each Station serving as an altar in one of the lateral chapels which stretch along both sides from the transept to the front doors, paved with rich mosaic and decorated with 20 large and artistically crafted chandeliers. Radiating out from the sanctuary are the chapels of the Blessed Virgin, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Saint Joseph, Saint Paul and Saint Francois Xavier, also decorated with stained glass images which relate to the themes of each altar.

It is under the vaults of this temple that, on great ceremonial days, crowds of Frenchmen, Annamites, Chinese and Indians gather and the liturgy unfurls in all of its inimitable majesty.

Since the month of October 1913, a thousand electric lamps, installed by M Soullard in the chandeliers and around the columns, have added a new shine to the beauty of these ceremonies. It is above all in the Pontifical Masses and on the day of the First Communion of the Children that our beautiful Cathedral is adorned with all its finery and shines in all its light. In particular, we will remember for a long time the extraordinary pomp, the rich ornamentation, and the magnificent songs on 17 October 1909, when 5,000 people crowded into the Cathedral to honour St Jeanne d’Arc, beatified just a few months before by Pope Pius X.

Beside these extraordinary solemnities, the preparation of which require more time and more work, the occupations of the parish priest of Saigon are the same as everywhere else; “his time, as regards the administration of his parish, is divided between administering the sacraments, visting the sick, giving instruction to children, and serving religious communities.” Such was, in summary, the view of M Le Mée, the third parish priest of Saigon.

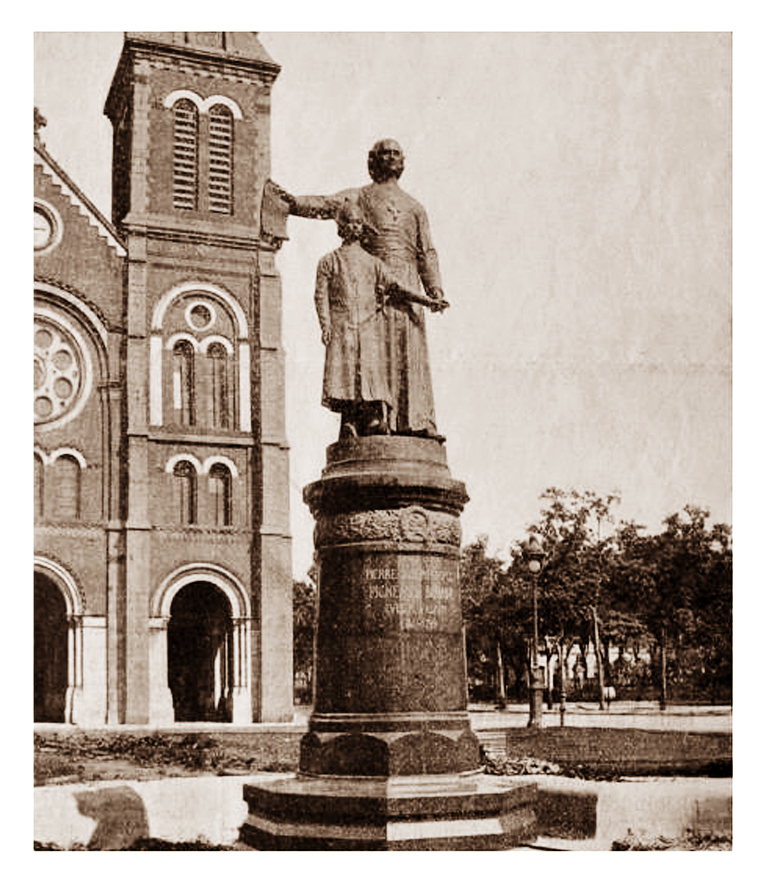

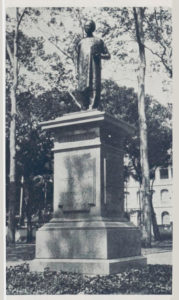

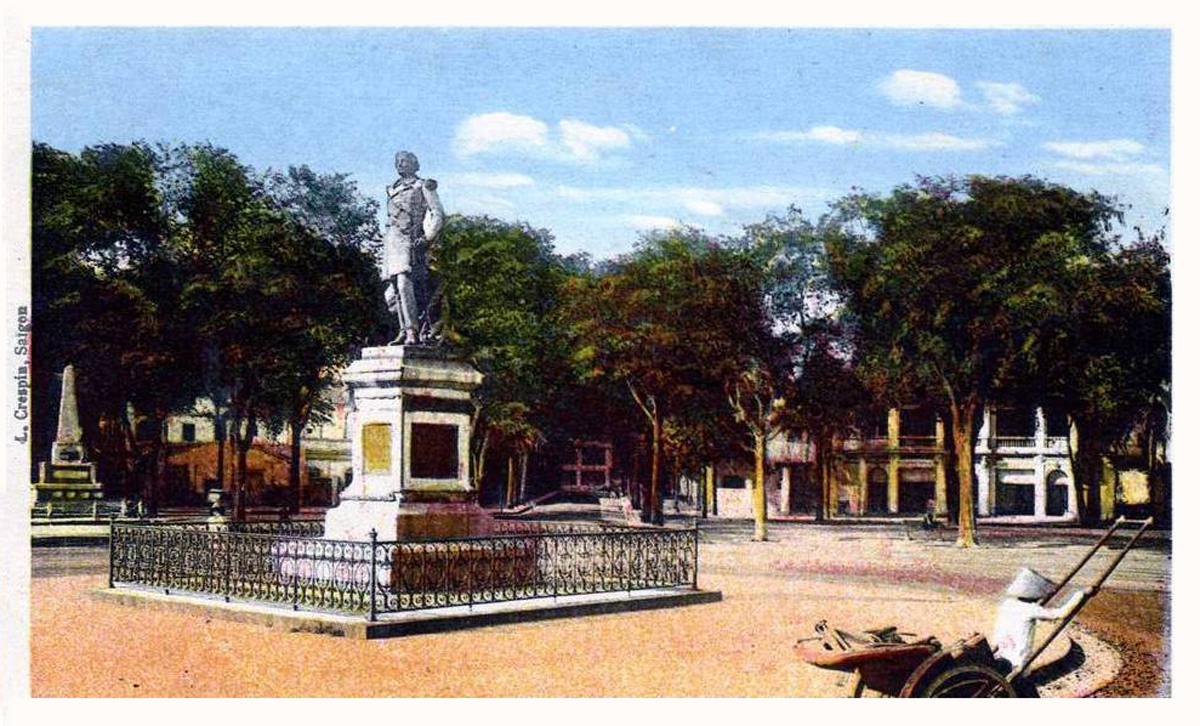

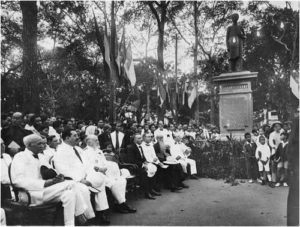

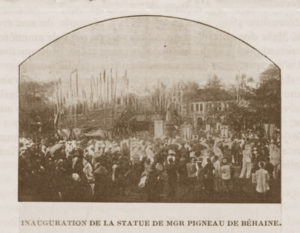

The Pigneau de Béhaine statue in front of the Saigon Cathedral in the early 20th century

M Le Mée was succeeded in 1898 by the current Apostolic Vicar of Cochin-China, Lucien Mossard, who established in the parish the Work of the Tabernacles, the purpose of which was to furnish the poor Christians of the Mission with the necessary ornaments for Divine Worship. The ladies who were part of it contributed their money and their labour to the making of these ornaments. The work, which counts some 60 members, prospered as long as it was directed by Mesdames Teillard d’Eyry and Beer; However, it then suffered the fate of many parochial works of its kind which have been attempted in countries like ours. These sorts of works have no chance of sustaining themselves for a long time, for the simple reason that most families of officers and employees come here only to spend two or three years at most, They are soon replaced by others who do not make a longer stay, and their work soon disappears along with the elements of which it was formed.

Monseigneur Mossard, who was to leave the parish to take charge of the government of the Mission, begged M Moulins, a missionary for many years in Mytho, to come and replace him in the parish of Saigon. M Moulins occupied this latter post only from April 1899 to January 1900, when illness forced him to go to Hong Kong, where he died. He was succeeded by M. Charles Boutier, who remained until March 1906. In 1902, in front of the Cathedral, in the middle of the garden which adorns the square, was erected the statue of Monseigneur Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran. This statue, the work of sculptor Lormier, depicts the great Bishop extending his arm to his pupil prince Canh, and holding in the other hand the edict of the French government which helped restore that young prince’s father to his throne. Monsignor Mossard, surrounded by a numerous clergy, gave the benediction to the monument with great solemnity.

Governor General Doumer, Lieutenant Governor Lamothe, Admirals Pottier and Bayle and all the civil and military authorities, as well as the great notables of Cochin-China, attended this imposing religious and patriotic ceremony. Numerous delegations from the Annamese parishes in the neighbourhood of Saigon, who had come with their banners, could be seen massed around the lawn, in the middle of which stood the statue of the Bishop of Adran.

Inauguration of the Pigneau de Béhaine statue in front of the Saigon Cathedral in 1902

In this way were the Church, France and Annam gathered together to honour worthily the hero of the day, Monsignor Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran. His memory will be perpetuated by this high monument in his honour, which will remind future generations of the great influence he has exercised over the future of this country, and the services he has rendered to Annam, France, and the Church.

No important event worthy of notice has taken place since that time, apart from the great feast in honour of Jeanne d’Arc, which I mentioned at the end of the notice I gave on the Cathedral.

In March 1906, Mr. Boutier returned to France for health reasons. Eugène Soullard has succeeded him to this day in the administration of the parish.

The Christian population of the parish of Saigon has hardly changed over the last 10 years. It now amounts to about 5,530 souls, including 4,000 Europeans, 800 Indians, 700 Annamites and some 30 Chinese. It has, however, decreased considerably with regard to the Europeans since the mobilisation in 1914. The pagan population is approximately 45,000.

Eugene Soullard, Parish Priest,

Presbytery of Saigon, 13 November 1917

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now and Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.