Delteil travelled to Saigon on the Messageries maritimes vessel Oxus

In March 1882, Arthur Delteil, retired Chief Pharmacist of the Navy, left Marseille on the Messageries maritimes vessel Oxus and travelled to Saigon, where he stayed for a year. This is the first of three translated excerpts from his book Un an de séjour en Cochinchine: guide du voyageur à Saïgon, published in 1887.

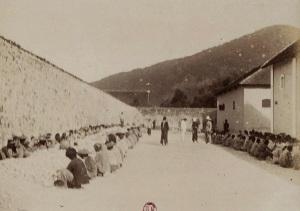

Prisoners on Poulo-Condor in 1895 by Jean-Marc Bel

At 6am on 18 April, we passed the large island of Poulo-Condor [Côn Sơn], which belongs to us and serves as the penitentiary for our colony of Cochinchina. At 5pm, on a calm sea, we anchored off Cap Saint-Jacques [Vũng Tàu] at the entrance of the Saigon River, waiting for our pilot and for the hour of the high tide.

Cap Saint-Jacques is the point where all ships coming to Cochinchina converge before making the journey up river to Saigon. It may be seen from afar, provides an easy landing and is topped by a first class lighthouse.

At the foot of the mountain in Cap Saint-Jacques, we built some houses for the staff who manage the under-sea telegraph cable which leads north from this part of the coast and is used to report the impending arrival of ships to the authorities in Saigon.

Cap Saint-Jacques in 1895 by Jean-Marc Bel

Cap Saint-Jacques forms part of the granite mountain massif of the province of Baria. In the early years of their occupation of Cochinchina, the French authorities were attracted by the location of Cap Saint-Jacques on the coast and conceived the idea of building a convalescent hospital there.

However, after two years of testing, they were obliged to abandon this hospital, because they found that the soldiers who were sent there became even sicker than the ones who had been left in Saigon. A similar attempt made briefly on Poulo-Condor, an island swept by strong sea winds and situated at an altitude of several hundred metres, was no more successful.

However, this is a project which should be returned to later, when we have better studied the causes that made these early attempts fail; because it seems that both Poulo-Condor and Cap Saint-Jacques enjoy healthy conditions far superior to those of Saigon, which is located a long way inland and only rarely receives sea breezes after they have already passed over the muddy rice fields.

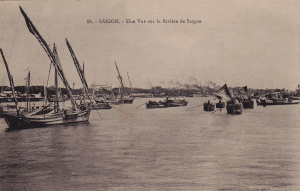

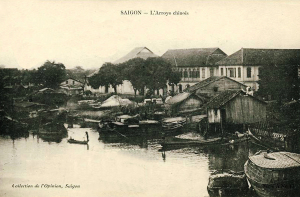

The Saigon River in 1900

At 3am on 20 April, we finally entered one of the mouths of the Donaï, one of two major rivers which flows through Cochinchina. The only obstacle which we encountered on this beautiful artery was a large bank of coral located near its mouth which can only be surmounted at high tide. Surely some dynamite and several hundred thousand francs would quickly blow away those madrepores.

It took about three hours for us to reach Saigon. As we sailed up river, we felt the sea breeze abandon us, its place taken by a hot, heavy and humid atmosphere. The thermometer read 31°30 and our bodies began to sweat profusely, leaving us anxious and exhausted as we breathed in the damp mist which rose from the marshes and extended in all directions, as far as the eye could see.

Glancing over the land which surrounded us, we were gripped by the impression which all Europeans feel when travelling through this country. The river which carried us rolled its yellow waters between two almost drowned shores, lined nearly all the way by stilted hits and clusters of trees and coconut palms.

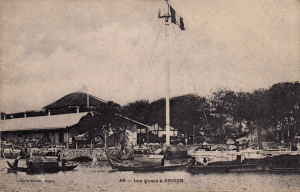

The Messageries maritimes quay

Behind this picturesque and charming backdrop of villages arranged scenically amidst nests of greenery, we could see nothing but flooded rice fields crossed by many arroyos. Everywhere was water and mud; it resembled a primeval scene of land in the process of formation from alluvial soil carried by the Mekong and Donaï.

By midday, as the hot sun beat its perpendicular rays down on this vast muddy plain gorged with moisture and decaying organic matter, we understood that the climate of this country, with its heavy rain and humidity, was little suited to the constitution of Europeans accustomed to more temperate latitudes.

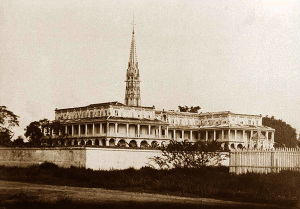

The country was so flat and so low that the river flowed at the same level as the banks. From a distance, we could see the square towers of the Cathedral, the Palace of the Governor and several other monuments of Saigon. The panorama of the city was far from ungracious, and indeed, this view of the capital of our colony caused our hearts to rejoice, for we were very eager to reach the end of our long journey.

Greeting arrivals at the Messageries maritimes quay in 1895 by Jean-Marc Bel

At 8am on 19 April, the Oxus finally moored at the quay of the Messageries maritimes, after 32 days at sea and six stops!

Our arrival had been reported the previous day in Saigon by the Cap Saint-Jacques telegraph, so we were expected by colleagues and friends, who came aboard to welcome us and make themselves available to conduct us to our accommodation.

Gathering our luggage, we boarded a sampan, a lightweight indigenous boat piloted by an Annamite and his “congaï.” We crossed the arroyo Chinois [Bến Nghé Creek], a tributary of the Saigon River which separates the Messageries maritimes from the city, and on the other side we landed on a masonry pier lined with benches and topped by a large flagpole known as the Signal Mast.

This place is known by the familiar name of Pointe des Blagueurs (“Jokers’ Point”), and it becomes very crowded in the evenings, as after-dinner walkers come to breathe the fresh air of the river and watch the incessant coming and going of junks carrying their rich cargoes to the Chinese city of Cholon.

The Pointe des Blagueurs (“Jokers’ Point”)

From there, we got into one of the carriages of the country known as the Malabar, a type of square box on wheels drawn by a skinny little horse and driven by a Chinese driver who did not understand a word of French. By touching his shoulder with a cane, we could get him to go right, left or straight on.

Many new arrivals to the colony have found themselves in big trouble after entrusting their persons to the mercy of these Malabar drivers in the belief that they would make trustworthy guides. Instead, they delight in taking advantage of newcomers’ naïvety by driving them around the city at random and then demanding payment for a journey of several hours’ duration!

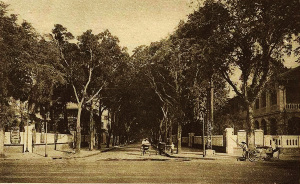

We travelled along a part of the quai du Commerce [Tôn Đức Thắng], then up rue Catinat [Đồng Khởi] to the Hôtel Favre, a large “caravanserai” in the style of the English hotels in Ceylon and Singapore. This hotel is a real boon for travellers; indeed, it is the only one among our colonies which has such good facilities.

Rue Catinat in the late 1800s

The man who designed and built the hotel [Elisée Favre] was a skilled cook and organiser of the first order. He saw the very large number of military and civilian passengers who arrived in the colony each year, and decided that he would build a hotel with all the facilities they needed. By offering large and well furnished rooms, an excellent restaurant, meeting facilities and good service, he succeeded in creating not just a temporary asylum for the newcomers’ first few days in the colony, but a decent hotel which attracted longer-stay guests. Indeed, so successful was M. Favre’s design that he eventually returned to France with quite a large fortune, leaving his successor a flourishing business.

The Hôtel Favre occupies almost the entire part of rue Catinat between boulevard Bonard and rue d’Espagne. It is located in the centre of the city, in the most lively and commercial street, close to the docks, the Messageries maritimes and the naval port.

A Malabar carriage on rue Catinat in 1895

On the ground floor there is a billiards room, a large restaurant for guests who want to eat alone or in small groups, and two or three other smaller dining rooms for long-stay residents. During meals, diners are kept cool by immense slowly-moving punkah fans, which are suspended above their heads.

Verandahs surround the building in front and behind. The first and second floors are occupied by rooms numbered from 50 to 60. A large, airy corridor divides them into two groups, those which have courtyard views and those which overlook the street. The latter are the most expensive and the most popular. The rooms are built and furnished to a uniform standard, without luxury, yet nonetheless with a certain level of comfort. Beside each is a bathroom with a shower, a bath and a tap which one only has to turn to enjoy fresh water in abundance.

This latter facility is a real stroke of genius on the part of the designer of the property, because in a place as hot as Saigon, being able to take cold water ablutions at any hour is a luxury which cannot be compared to any other!

A Saigon pousse-pousse

During the stiflingly hot months of April and May, when the thermometer never drops below 31° day and night, the greatest physical pleasure that one could have is to plunge into a bath of relatively cold water, bringing about a subtraction of heat and resulting in a relaxed state of well-being which lasts for several hours. These cold water baths permit us to endure the warmer months of the year without too much irritation.

This eager pursuit of guests’ well-being has contributed more than anything else towards the hotel’s success. So many officers have not hesitated to make it their home for the duration of their stay in Cochinchina, rather than renting a private house, with its obligation to furnish and the certainty that one would not be so well served with amenities of the type I have just mentioned.

Merchant houses on the banks of the arroyo Chinois in the late 19th century

The room rate at the hotel ranges from 13 to 15 piastres (63-73 Francs). As for full board, it offers a very affordable price to officers who have come to serve in Cochinchina, whose salaries are generally quite high.

For 30 piastres (130 Francs) per month, the long-stay guest will have 10 dishes to choose from, plus wine, ice, coffee and liqueurs – service included! This is why I opted to settle at the Hôtel Favre for the duration of my stay in Saigon.

Those who prefer to find their own place to live in Saigon are spoiled for choice. They can find small houses for rent at 75 to 100 Francs per month, or larger houses for rent at 125 to 150 Francs per month. It pays, therefore to share, which costs a lot less. A family is obliged to spend at least 100 Francs per month in rent.

As rental buildings can generate a lot of money in Saigon, those people who have made money in business, or have a small amount of capital to invest, frequently spend their money on building or buying properties to let.

Colonial buildings in Saigon

In this way, there are now many rental properties available, and it is relatively easy for those who don’t wish to live in a hotel to find a place to live.

However, renting a property means that one is obliged to furnish the house oneself, and also to meet the costs of installation. In this instance, one goes to the auction room on rue Catinat, which is located opposite the Hôtel Favre. This is where furniture, bedding, crockery, pots and pans and other household items are sold at a relatively cheap price on behalf of those who are leaving the colony.

For modest purchases, I also recommend the Chinese stores on rue Catinat, which sell lightweight, strong and comfortable beds and bamboo chairs at a really reasonable price. If one is not too fussy, one might also consider buying a Cambodian mattress, which can be folded for travel. A mosquito net must also be purchased to cover the bed, after which one is equipped with everything it takes to get a good night’s sleep.

Another Saigon pousse-pousse

The next task, if one is to eat at home, is to hire a domestic and a cook. The domestic is usually an Annamite and he costs a lot – 30-40 Francs per month, excluding food. Annamite domestics are usually young men aged 18 to 20 years, known as “boys.” Cooks are usually of the Chinese race and can cost up to 40 or 50 Francs per month. One is almost always satisfied, since the Chinese cook will rapidly become aware of the habits of European cuisine and the tastes of the people he is called to feed.

In the morning, one should give him money to go to the market and say: “With this you will buy me enough food so that I can eat well.” With the amount given to him, he will always manage to provide a good table for a relatively low price. But one should never count the change with him; if there is a difference to his advantage, that’s his business.

The Saint-Enfance

Families with children will require a female domestic. We can find fairly good ones at the Sainte-Enfance. They come straight from the care of the Sisters of St-Paul de Chartres, knowing how to sew, work and speak French. Unfortunately, when they are pretty they often turn bad, as frequently happens to girls of the same category in France. I’ve heard that these domestics provide adequate services. We must make do with them for lack of anything better.

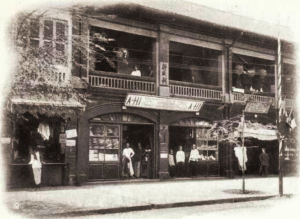

On my first day in Saigon, I was visited by several Chinese suppliers – launderers, tailors, shoemakers – who came to me offering their services. Each one of them presented certificates which commended them to the benevolence of newcomers to the colony.

For a subscription of 12.50 Francs, the launderer washes and irons all the clothes that one is likely to get dirty during the month. And God knows, in a country where we are always sweating, we must change clothes often enough!

Chinese shops on rue Catinat

In Saigon, the laundry is done only by men. You will find these Chinese launderers in the rue Catinat, where most members of their corporation are based. Ironing is one particularly interesting aspect of their work which deserves to be described. The ironer fills his mouth with a mixture of water and starch and uses his lips to spray a very fine mist of this liquid onto the garment in front of him, at the same time pressing the well-watered item of clothing over a heated pan filled with hot coals. Despite the primitive means used, the linen is always returned dazzling white and beautifully ironed.

As for clothing and footwear, the Chinese can make these so cheaply that that there is simply no need to bring a wardrobe full of clothes and footware out from France. Judge for yourself – a complete light blue flannel suit consisting of trousers, waistcoat and jacket will cost no more than 40 Francs, cloth included. Chinese shoemakers, in turn, will make a strong pair of boots from flexible black material for just 5 Francs.

French colons wearing flannel suits and helmets at the Messageries maritimes in 1895 by Jean-Marc Bel

Their work is not particularly elegant or refined; Chinese tailors and shoemakers do not create fanciful or trendy fashion items; they would be incapable of that. They just slavishly copy the models that you give them and their amibition is limited to this imitation. But their creations are convenient and quite in keeping with the needs of the climate.

A flannel suit and helmet is, in general, the costume worn by the majority of Europeans in Saigon. However, some young people have adopted the fashion of British officers in India and Singapore, that is to dispense with a shirt and wear next to the skin a white cotton jacket, buttoned up and down, which is changed every morning. This is clothing reduced to the bare essentials!

To read part 2 of this serialisation click here.

to read part 3 of this serialisation click here.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.