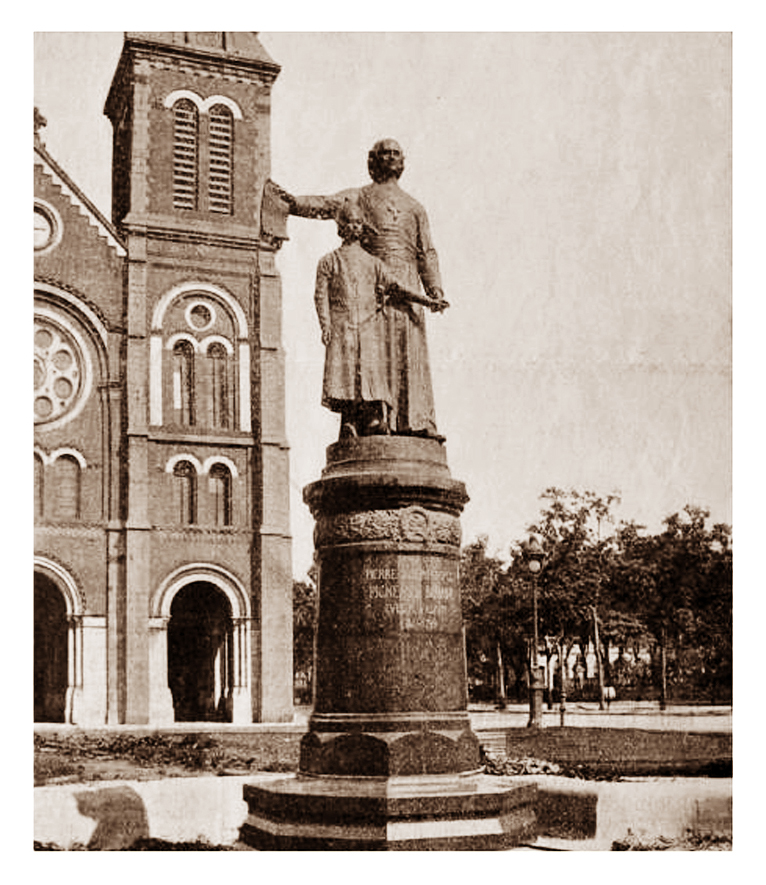

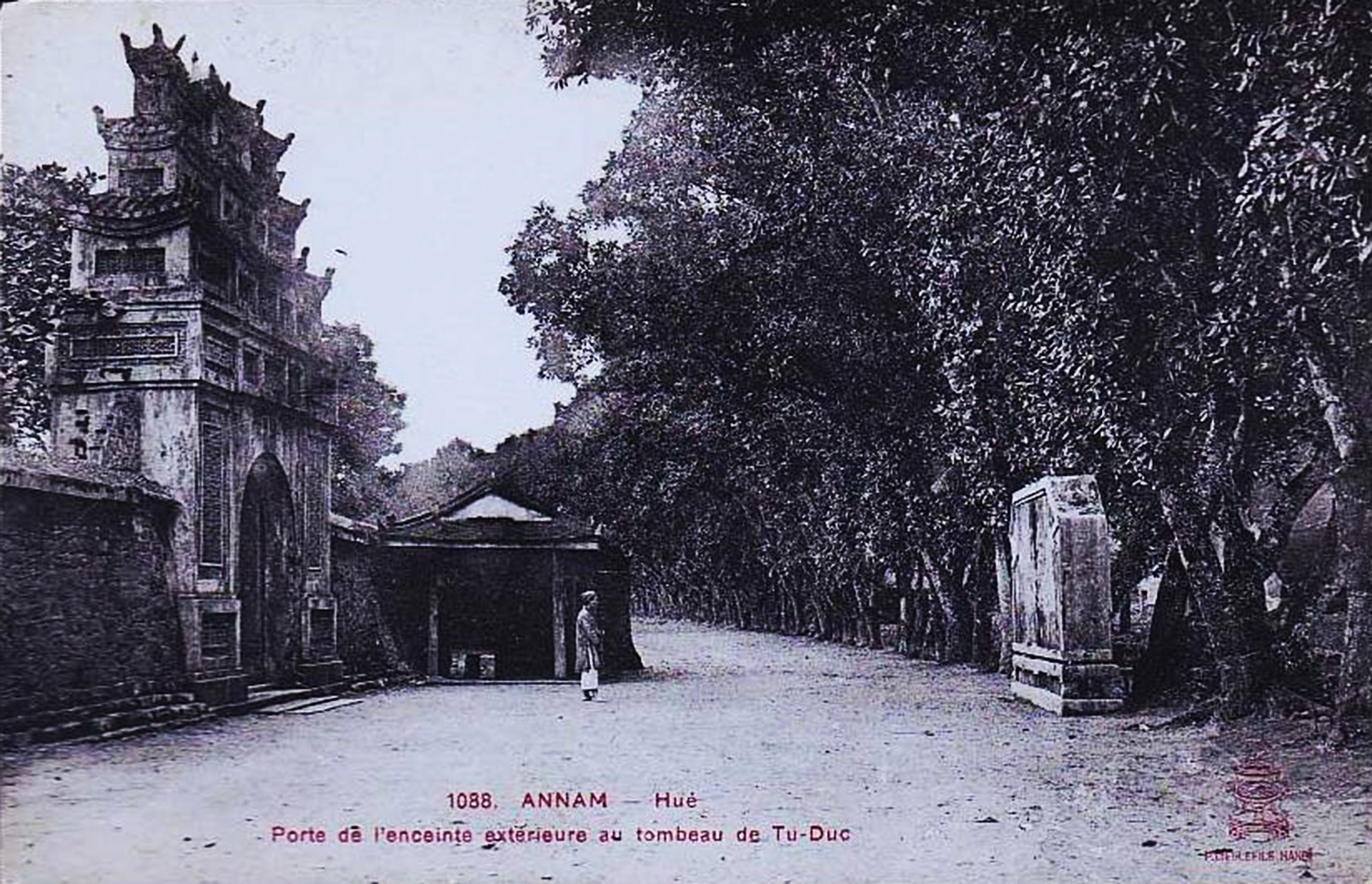

The Khiêm Mausoleum of Emperor Tự Đức (1848-1883), where the illegal excavations were carried out in December 1912

In late 1912, an illegal treasure hunt in the Tự Đức tomb compound in Huế reduced the 13-year-old Emperor Duy Tân to tears, ended the career of the Resident Superior of Annam Georges Mahé, and was cited by Vietnamese nationalist Phan Châu Trinh as one of the immediate causes of the Hà Nội bombing of 26 April 1913. Here is a selection of newspaper reports on the events surrounding the so-called “affair of the tombs.”

Straits Times, 17 May 1913: Hanoi bomb outrage – two French commandants killed, Europeans and natives injured

L’Avenir du Tonkin prints an extensive report of the bomb outrage in Hanoi mentioned in our telegraphic columns recently.

A bomb exploded on the terrace of the Hanoi Hotel on the evening of 26 April, killing two French superior officers and injuring a number of Europoeans and Annamites. The date mentioned was a Saturday, on which evening the hotel was more than usually crowded. About 300 people had assembled and were seated, some on the terrace, some in the restaurant room. The scene of pleasure and animation was rudely distubed just after half past seven by a loud report on the terrace and clouds of smoke ascended. This was followed by cries of pain.

Commandant Chapuis, one of the two French officers killed in the bombing of 26 April 1913

When the smoke cleared, it was seen that a number of people had fallen to the ground. Blood seemed everywhere on the floor, and windows were shattered. At once the cry was raised that a bomb had been thrown, and it was discovered that the miscreant responsible for the dastardly outrage was an Annamite. It had fallen right in the entrance to the hotel, mortally wounding Commandant Montgrand of the Son-Tay, and Commandant Chapuis, old comrades who had met to renew old acquaintance. They were seated at a round table in the entrance. Several people seated at the next table received terrible injuries and were removed to hospital. Others in different parts of the building were more or less injured, one man’s hat being riddled.

Despite the late hour, the news of the outrage spread rapidly, and soon all the officials, including the Governor General and the Police, were on the scene. Soldiers were posted in the cafés, and precautions were taken to prevent a recurrence of the outrage. Commandant Montgrand died after terrible suffering at 10 o’clock the same evening, and Commandant Chapuis expired at 1.30am. The police made 65 arrests. The funeral of the victims took place on Tuesday. It was attended by the Governor General and military officials.

Bulletin de l’Institut colonial de Nancy, May 1913

INDO-CHINA – De-Tham, our old enemy, died on 11 February 1913. His death can only serve the cause of peace.

On the other hand, the 26 April 1913 bombing in Hanoi was a revolutionary act which could not be considered a simple incident. It has drawn our attention to the wisdom of monitoring in China those nests of conspiracy which are likely to organise unrest in Tonkin. Punishments have been handed out to 85 defendants: seven were sentenced to death, 14 imprisoned and 60 sentenced to forced labour or prison. This shows well enough the extent of the criminal process, but from the French point of view, there will be much to fear if the indigenous people harbour feelings of union with these conspirators who have learned to handle bombs.

It comes soon after “affair of the tombs of Hue,” which certainly caused injury to the traditionalist sentiments of the Annamites. It was an administrative error to carry out excavations in an imperial tomb which, in the eyes of the native people, had thus suffered desecration.

Le Journal, 1 May 1913: The bombing of Hanoi

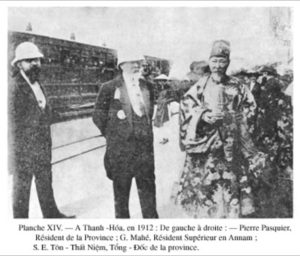

Georges Mahé, Resident Superior of Annam, who lost his job for carrying out the illegal excavations

Monsieur Georges Mahé, the Resident Superior in Annam, has been recalled; he will be given compulsory retirement.

The Governor General of Indochina has not yet addressed new information to the Minister of Colonies about the bombing of Hanoi; we think that Monsieur Sarraut has not wished to send details on the progress of the investigation by cable, preferring to ship them by post and thus to exclude any possibility of indiscretion. Be that as it may, the report of Monsieur Sarraut on this case is eagerly awaited; we hope to receive it via the first Trans-Siberian mail.

On the subject of Monsieur Sarraut, the rumour was spread that the Governor General had also been recalled, but it is not so. Since his departure, the Governor General, who went to the Far East with the firm intention of carrying out long-term work, has never taken any leave, and right now, when his presence in the colony is most needed, he would never consider taking the ship home. As for the government, it has no reason to recall the Governor General, who has its confidence. However, just a few days before the attack in Hanoi was known, the Minister of Colonies recalled from office Monsieur Georges Mahé, Resident Superior in Annam.

Having been told confidentially by an indigenous person that treasure was hidden in the area around the tomb of Emperor Tu-Duc, Monsieur Mahé asked the Governor General for permission to proceed with excavations inside the sacred enclosure, but Monsieur Sarraut forbade him from doing so. Ignoring this prohibition, Monsieur Mahé obtained from ministers of Annam a resolution authorising an excavation, and proceeded with the violation of the tomb of Tu Duc. The indigenous population was outraged, and Monsieur Sarraut, sharing their indignation, ordered the cessation of excavation and reported the incident to the Minister of Colonies. It was for this reason that Monsieur Mahé was recalled. We understand that he will be given compulsory retirement as soon as the matter has been heard by the minister, his personal responsibility for the affair being, we are assured, absolute.

The violation of the tomb of Emperor Tu Duc gave an extremely disastrous impression in Annam. The young Emperor Duy Tan, who is 13 years old, visited the tomb of Tu Duc, and there, bursting into tears, he reproached his ministers, who were present, for the sacrilegious desecration of which they were guilty. His reaction was, we are told from Hue, very moving.

All of these events occurred before the bombing of Hanoi; however, we are assured by cable from Saigon that there is no correlation between these incidents and the attack.

Georges Mahé, Resident Superior of Annam is received in Thanh Hóa province by its Resident Pierre Pasquier and provincial governor Tôn Thất Nhiệm in 1912 (BAVH 3, 1941)

It is difficult to pronounce on the case before circumstantial details are available; but we believe that the spirit of the indigenous group which manufactured and launched the bombs was determined by various causes, including Chinese revolutionary agitation involved in anti-dynastic activity against Duy-Tan and renewal of the alcohol monopoly. Perhaps the affair of the tombs also added to the excitement of the agitators.

Whatever the case, Indochinese officials currently in France – and they are of the highest grade – regard the bombing in Hanoi as a very serious symptom. According to the latest news from Hanoi, the funerals of Commandants Chapuis and Montgrand have been celebrated in this city with solemnity. Monsieur Albert Sarraut addressed an emotional farewell to the two officers who died in battle; The French and the indigenous population remained calm.

Fernand Hauser

Les Annales coloniales: organe de la “France coloniale modern,” 6 May 1913: Cochinchina

Although we are still unable to speak with absolute certainty, there is now more and more reason to believe that those who carried out the armed attack of 26 April 1913 (our readers will already know the detail: a bomb in Hanoi killed two French officers) have a close relationship with Chinese revolutionaries. The Cochinchina community believes that this is the natural consequence of our cowardice towards the indigenous people.

The Governor General suspects further that one of those who has funded the revolutionaries in our colony is the brother of Sun-Yat-Sen, but thus far he has sent no evidence about it to the Department.

Preparations for attacks had been made for several months already in Shanghai, Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Macau. The main Annamite involved would be the son of Te-Kieu, a big landowner and former gang leader in Tonkin.

Vietnamese nationalist Phan Châu Trinh (1872–1926)

A meeting took place in Saigon on 30 April to protest against the policy of abandonment followed towards the indigenous people, which, by encouraging protest, is dangerous by virtue of the audacity and ambition it gives to the Annamites. Yet, while this meeting was going on, another voice was heard here in Paris.

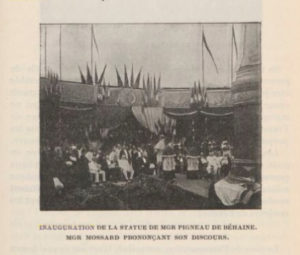

The mandarin-scholar Phan-Chau-Trinh (who was sentenced to death in 1907, then pardoned and sent to Poulo Condor, where he spent three years before his release on the intervention of our collaborator Maurice Viollette, before being given permission to enter France), has confided to our friend Fernand Hauser, in the Journal.

In particular, he told him: “The alcohol monopoly has been renewed, although it was solemnly promised that it would not be; our patriots still languish in Poulo Condor prison, although they were promised grace; the education we demand is always denied us; the contempt of which we complain is always thrown at us; and to all these faults are added new ones: Now they have even violated the sacred tomb of Emperor Tu-Duc in search of money!

In that there are both truths and falsehoods. Phan-Chau-Trinh-mocks the public when he says: “There is talk now of establishing a regime of terror in Annam. That’s easily said. But when you’ve arrested 500,000 persons and cut off their heads, what then? You will only inflame passions.”

But it becomes truly grotesque when the mandarin clearly shows us what sin we have committed by increasingly admitting our Annamite protégés to various administrative positions, saying: “Do you not think that it is in the interest of France to get along with the Annamites? On the day when it gives the people of Annam their autonomy, France, by instructing us, by preparing us for freedom and by giving us that freedom peacefully, would retain our sympathies, and we would remain close friends and allies.”

Oh come on! Was it for such a comedy that Annamite land was watered everywhere with the best French blood? Our dead would rise from their Asian mass graves in protest on the day when France would act this way. For there is no doubt that, after many years of political carelessness, according ever-increasing autonomy to the indigenous people, they would now waste no time expelling our compatriots from the land they conquered at the price of their lives.

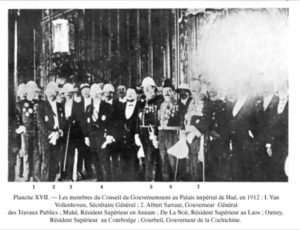

Members of the Council of the Government pictured at the Imperial palace in Huế, including Governor General Albert Sarrault and Resident Superior of Annam Georges Mahé (BAVH 3, 1941)

Where Phan-Chau-Trinh was mistaken – because we refuse to believe that he abused the good faith of Monsieur Fernand Hauser – is when he talked about the contempt for the French which has been nurtured amongst the indigenous people. During the rule of Monsieur Sarrault? Nobody would believe it for a moment, not least our settlers! What would they say?

Le Temps, whose communiqué is official, said that the Indochinese police had been informed for several months of preparations by revolutionaries based in China, and before 26 April they had succeeded in preventing any attacks.

Phan-Chau-Trinh infers that the attack of 26 April is a direct consequence of the famous “affair of the tombs.” Read more:

“What do you think the population thinks of that? Ah! When I learned about the sacrilege committed in Hue, I shuddered! I thought something bad might happen, in fact I warned a friend of the terrible consequences of this desecration, which had occurred after so many previous harmful acts! I know that the government was informed of the letter in which I raised my concerns. And just 22 days after I wrote, that bomb exploded in Hanoi!”

Phan Chau-Trinh probably believes that in France there are only people ignorant of all that which has been contrived for years by indigenous communities to try to make us swallow such nonsense. That we should submit to the demands of the Annamites for privileges which prejudice our own, that’s something we will never permit, indeed only a fool or a madman would agree to such a thing. It would be the death of all colonisation!

A word in conclusion. Phan-Chau-Trinh also told Mr. Fernand Hauser: “This oppressive regime [it’s the so human and so benevolent regime of Albert Sarraut which Phan-Chau-Trinh judges thus!] is the wood accumulated in the hearth, and only a small spark could start a fire! Beware! I love France. I hope with all my heart that it retains its reputation for justice and that it will wish to weigh the public interest and specific interests regarding our country; enabling it to see that it has everything to gain by giving us the necessary reforms.

Vietnamese nationalist Phan Châu Trinh (1872–1926)

The French administration will say, perhaps, that nothing is urgent, that the situation is not serious. I am of the opposite opinion, and it’s because I love France deeply that I tell you this. To those we love, we owe the truth.”

These sentences undoubtedly contain a threat, the truth of which the mandarin has incompletely articulated. If Phan-Chau-Trinh knows something and believes he can advance the facts, if he loves France, his duty is clear. If he loves his country, even in his own interests, his duty is to dispel the misunderstandings of these ambiguous words. And perhaps the duty of the authorities would be to question him further on this.

The bombing of Hanoi has deeply moved, as we have said, the Saigon population. We have already reported on a meeting held recently in Saigon, which was attended by over 600 of our compatriots. The chairman of the meeting, Monsieur Foray, sent us the following telegram:

“Saigon, 3 May – The French people of Cochinchina, gathered in a large meeting under the chairmanship of Monsieur Foray, are rightly concerned at the recent series of crimes, including that in Hanoi, and believe that the situation has been aggravated primarily due to the policy advocated by some parliamentarians, who are unaware of the real relationships existing between the various elements inhabiting our colony. It is they who have spread their false humanitarianism and sought unhealthy popularity by exciting the dregs of the indigenous population against alleged colonial excesses, even at the expense of the vast majority of honest and loyal Annamites. The said French people, convinced that this situation poses the most imminent danger to the interests acquired by our compatriots at the price of innumerable sacrifices consented by themselves in men and money since our establishment in Indochina, protest strongly against the continuation of this harmful policy. They demand the full reinstatement of indigenous justice, in order to remedy a situation which has become unbearable, and to prevent the inevitable recurrence of attacks similar to those already perpetrated, and to this end they are ready if needed to support their legitimate demands by all means within their power.”

It should be recalled that out of Saigon’s 70,000 inhabitants, there are 7,000 Europeans, including over 6,500 French (civilian population), and 2,000 French in the rest of Cochinchina. This telegram reflects clearly the opinion of the majority of French people in the colony.

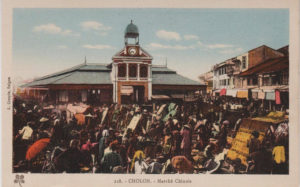

Chợ Lớn in the early 20th century

We should add that Monsieur Foray, a lawyer in Saigon, is a candidate for a parliamentary seat.

Recently, on 27 or March 28, a band of 500 Annamites, enlisted by the enemies of our domination, marched out of the interior, in particular from Mytho, Tanan and the banks of the Vaïco, to disturb the peace in Cholon. A total of 80 arrests were made. These individuals were dressed in clothes made almost all from white cloth. The security police raided the home of a rickshaw company manager named Tu-Mang on quai Testard, Cholon, seizing 16 combat swords. They are continuing their search for other weapons. Searches were also made at the premises of an indigenous hôtelier, but they found only the works of Pascal, Rousseau, Descartes and Lamennais. The conspirators, who were mainly engaged in crimes against persons, said they left their family homes at the instigation of certain leaders to come in great number to Cholon and Saigon. There they were to have been given weapons and all necessary instructions. One of the leaders was a certain Truong, of Tang-Tru, in the province of Cholon. Numerous patrols are now criss-crossing Saigon and Cholon, their officers are armed with revolvers. Many of the European population have also bought Brownings and even Mausers and Lebels – the city’s armourers are doing a great trade at the moment. The Administrator of the province of Cholon posted a large sign warning the Asian population against the actions of some individuals and demonstrating the absurdities contained in the seditious placards. His call for peace has, it appears, produced favourable results among all the Asian population.

Le Matin: derniers télégrammes de la nuit, 19 May 1913: The case of the tombs of Annam – the first punishment

In response to the question put to him by Monsieur Doisy, Socialist deputy from the Ardennes, who wished to know whether responsibility was being sought regarding the desecration of the imperial tombs of Hue and what sanctions had been or would be taken, the Minister of the Colonies made this statement, which was published yesterday in the Journal officiel: “The responsibilities have been thoroughly investigated and the necessary measures taken.”

The Khiêm Mausoleum of Emperor Tự Đức (1848-1883), where the illegal excavations were carried out in December 1912

The first punishment was given to Monsieur Georges Mahé, Resident-Superior of Annam, who has been placed in retirement. Monsieur Mahé, who is 53 years old and has completed many years of service, will soon return to France. There will be other punishments. Those will most likely be handed out after Governor General Sarraut has, by a thorough enquiry, established the responsibility of each person. Moreover, only after much thought will decisions will be made, with all the necessary sang-froid.

Le Petit Parisien: journal quotidien du soir, 21 May 1913: Profanation of the tombs of Hue

Marseille, 20 May – Monsieur Georges Mahé, Resident Superior of France in Annam, arrived in Marseille this morning on the ship Ernest-Simons of the Messageries maritimes Far East courriers. Asked on arrival about the excavations that were made last December in the imperial tombs of Hue, Monsieur Mahé refused to provide any information, saying that he had nothing to say as he had not yet met with the Minister of Colonies.

As yet, the news of the forced retirement of this official, published a few days ago, has no official status. It is only after the Minister of Colonies has spoken to Monsieur Mahé that he will make a formal announcement.

Let me say first that the desecration of the imperial tombs of Hue has no connection with the bombing of Hanoi on 26 April, a work planned long ago by Annamite revolutionaries based in China.

According to reports, the Resident Superior in Annam was the victim of intrigues which he would not be happy to acknowledge. Several ministers, part of the Regency Council of the young Emperor of Annam, suggested to Monsieur Mahé that secret treasure was hidden in a royal tomb in Hue. The Regency Council is divided into two rival clans, each of which deploy a prodigious arsenal of tricks and machinations. In the circumstances, one of these clans would eagerly have seized any opportunity to lead our protectorate into trouble.

The Khiêm Mausoleum of Emperor Tự Đức (1848-1883), where the illegal excavations were carried out in December 1912

The Annamite population has conserved a religious respect for the person of its sovereign. In addition, it observes to a very high degree the worship of ancestors. The excavations at the royal tomb in Hue were seen as a desecration, because according to the Annamite custom, the body is never buried in the actual tomb assigned to it. The imperial tombs are spacious gardens with lawns, walkways and woodlands, and it is in any part of a tomb enclosure, with no external distinguishing mark, that a body may be buried. In this way, taking a pick axe or shovel to any area inside the enclosure, according to indigenous beliefs, risks violating the royal corpse.

This is why the excavations, although they were quickly stopped, produced a feeling of discontent which was quickly exploited by xenophobes. Monsieur Mahé, who had thought to enrich the reserve funds of the colony without damage to anyone, was thus heavily deceived. These, we believe, are the facts with which he has been charged, and for which he must now find justification.

Le XIXe siècle: journal quotidien politique et littéraire, 22 May 1913: The affair of the tombs of Annam

Marseille, 20 May – This morning at 8am, the Messageries Maritimes steamship Ernest-Simons arrived from the Far East. On board was Monsieur Mahé, Resident-Superior of Annam, who had been called home by the Minister of Colonies to provide explanations on the violation of the imperial tombs of Hue, an act which was committed last December.

Interviewed after coming ashore, Monsieur Mahé refused formally to answer any questions, saying that he had a duty to provide explanations to the Minister first. Monsieur Mahé left for Paris in the evening.

Le Temps, 11 July 1913: Indochine: A short speech by the King of Annam (from our special correspondent)

Hanoi, 12 June – According to agency telegrams, the Governor General has installed Monsieur Jean-François Charles as Resident Superior in Annam, in succession to Monsieur Mahé, whose departure was prompted by the famous “affair of the tombs.”

The Emperor Duy Tân as a child

The memory of this unfortunate incident is completely erased today, and the action taken with regard to Monsieur Mahé seems to have produced a favourable response in the Annamite community. An outstanding and entirely unexpected event has also shown the excellent disposition of the court of Annam. His Majesty Duy-Tan usually responds to speeches by the Governor General merely by reading a short statement in the Annamite language, which is then translated directly by an interpreter. This time, however, to everyone’s surprise, the king spoke in French and delivered the following speech, which he had prepared himself, without the knowledge of the Governor General:

“I would like, Governor General, to express my gratitude and to tell you what a precious comfort you have been for everyone here in the wake of the sad events which plunged Tonkin and all Indochina into mourning. Annam feels today as never before the need for the support and protection of France, and you came, responding to the secret call of my heart, like the silent desire of the Annamite people, to bring through your presence the certainty of that protection, the assurance of the interest that a great nation carries to her adoptive child.

On behalf of my people and myself, I also address to you, Governor General, the expression of our gratitude for the appointment of Monsieur Charles to the post of Resident Superior in Annam. We have known him for a long time and I am happy to say here that he has our confidence.

I drink to the health of the President of the French Republic, to your health, Governor General, and to the health of the Resident Superior.”

For those who know Annam, this royal initiative is a small revolution. I understand, moreover, that the king has spent much time with the Governor General and has testified to his satisfaction at the liberal policies being followed by France in Indochina.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.