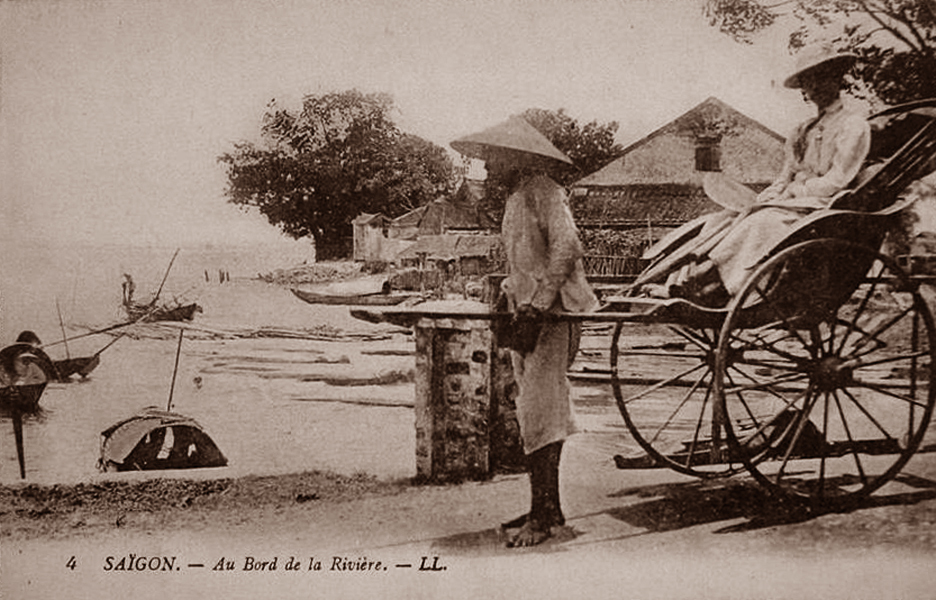

Saigon – next to the river

First published in the 1869 journal Annales des voyages, de la géographie, de l’histoire et de l’archéologie, edited by Victor-Adolphe Malte-Brun, Charles Lemire’s article “Coup d’oeil sur la Cochinchine Française et le Cambodge” gives us a fascinating portrait of Saigon-Chợ Lớn less than 10 years after the arrival of the French.

Cap Saint-Jacques and the journey up river to Saigon

We are now in sight of cap Saint-Jacques [Vũng Tàu], where a lighthouse was inaugurated on 15 August 1862.

Cap Saint-Jacques Lighthouse

That lighthouse is located on the south summit of a chain of rocky and forested mountains, which has 139 metres of elevation and the advantage not being shrouded in clouds like neighbouring peaks. It stands 8 metres high. The lighthouse is a first class installation. Its light is fixed, and it is visible 30 miles out to sea.

We will soon see the French flag floating over a fort which was built between the mountain and the sea. It’s the military post of cap Saint-Jacques, which is connected to the lighthouse by a road of three kilometres, dug into the same side of the mountain. It is a very picturesque road and practicable on horseback. The fort is controlled by a naval officer who monitors the coming and going of ships in the harbour below.

The semaphore system of the lighthouse is used to communicate with ships as they enter or exit Coconut Tree Bay (baie des Cocotiers). Dispatches and other communications are forwarded to the cap Saint-Jacques lighthouse by electric telegraph, and thence directly to Saigon.

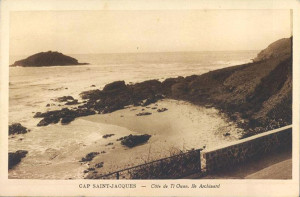

Coconut Tree Bay is shaped like a horseshoe. In the background, standing out against a blue sky, are the graceful plumes of many coconut trees, from which it gets its name.

At one end of the bay stand the green wooded mountains of the cape, and on the other the massif of Gan-ray, flanked by a circular Annamite fort which we took and then abandoned. It is in this bay, amidst a smiling landscape, that we may find the cap Saint-Jacques fortress, next to which lies the telegraph office. The signal mast at the corner of the fort is not just a semaphore installation. It is used to indicate to pilots, by means of signals of local convention, which vessels are lying offshore, and to inform the captains of ships at anchor, as well as those making their way into the bay, when they are sent a telegraph communication. This latter signal flag consists of a white ball with horn supported by a white and blue flame. The colour of the ball varies according to the number of vessels present in the harbour. The bay of Gan-ray provides shelter from the monsoons, but it is used very little by shipping.

Baie des Cocotiers, Cap Saint-Jacques

Coconut Tree Bay is well sheltered from the northeast winds, and this is where the pilot boats are stationed. Chinese and Annamite junks and other commercial vessels also anchor here. The junk owners get their supply of wood in the nearby forests, and their water from the spring located between the cemetery and the foothills of the Gan-ray massif.

Chinese compradors and ship supplies merchants come and go between Coconut Tree Bay and Can-Gio.

The price of pilotage for ships of war is as follows:

Cap Saint-Jacques to Saïgon

– Steam ships 4 piastres

– Sailing ships 8 piastres per metre draft

Can-Gio to Saïgon

– Steam ships 3 piastres

– Sailing ships 8 piastres per metre draft

The price of pilotage for commercial ships is as follows:

Cap Saint-Jacques to Saïgon

– Steam ships 5 piastres

– Sailing ships 8 piastres per metre draft

Can-Gio to Saïgon

– Steam ships 4 piastres

– Sailing ships 8 piastres per metre draft

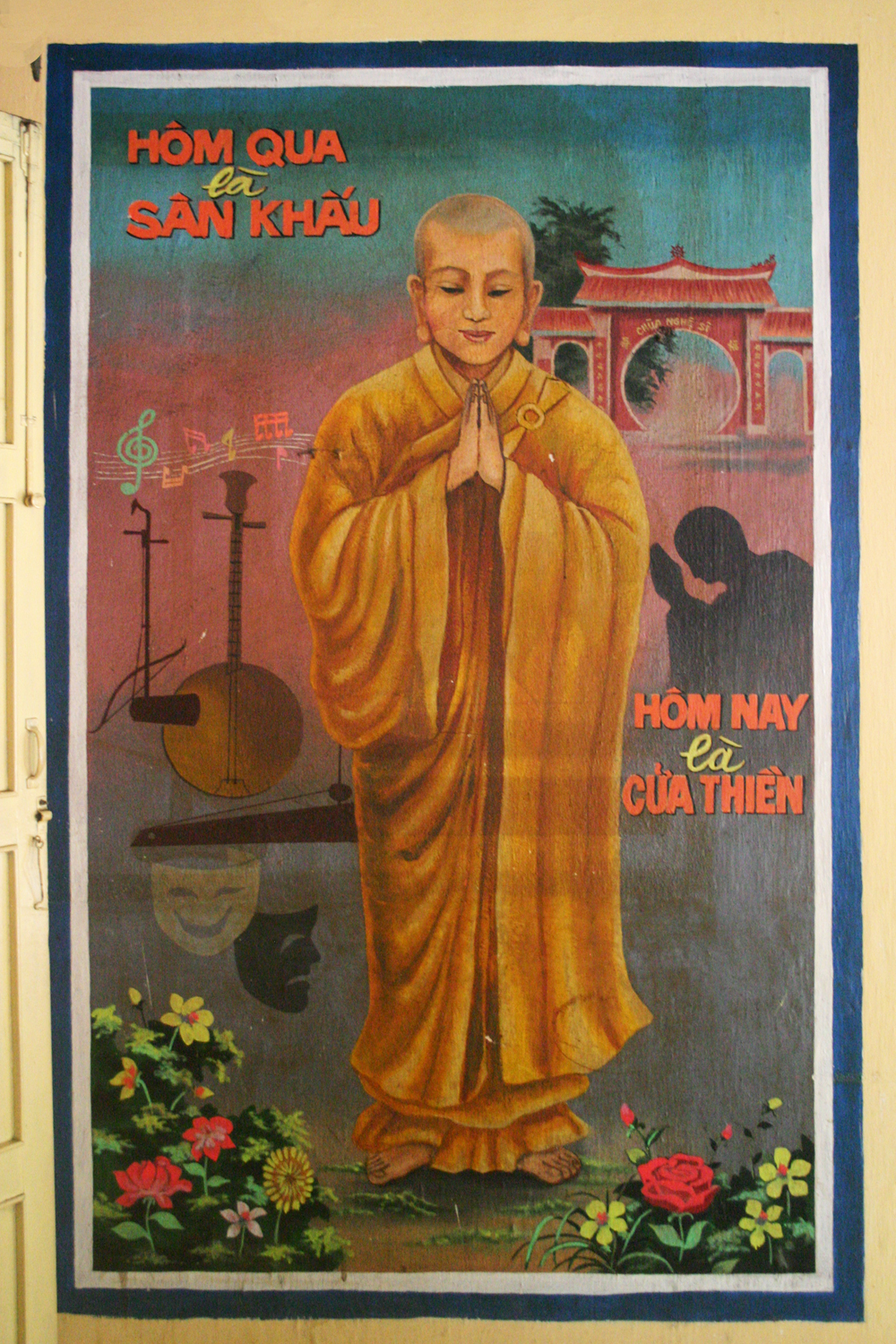

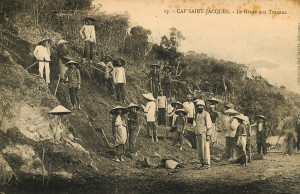

Road construction at Cap Saint-Jacques

That makes 3.33 piastres or 18.52 francs per French foot, and 3.05 piastres or 16.92 francs per English foot.

For vessels towed from Can-Gio to Saïgon, 5 piastres.

For sail pilotage from cap Saint-Jacques to Can-Gio, 2 piastres.

At night, the pilot schooners carry lights on their bows. As this harbour is open to the southwest winds, ships, junks and pilots shelter from the monsoon at Can-Gio, at the entrance to the Saigon River.

A floating beacon has been established at this location to indicate the route to ships at night time. Can-Gio village is situated 11 miles from cap Saint-Jacques. Here, shipowners may procure poultry, pork, fish and fruit. It is also from here that fish are shipped to Saigon and Cholon by fast boat. As for the tiny village of Coconut Tree Bay, it consists of around 20 fishermen huts and doesn’t have a proper market. A number of Chinese have opened stores here and they sell some food for consumption by Europeans.

In the “Valley of the Lilies,” a large area of marshland situated next to the cape, we may find sacred Pink Lotus flowers (Nelumbium speciosum) and hidden amongst the dunes, covered with thick foliage, we can also see beautiful gardens with coconut palms which provide the lighthouse with the oil it consumes. The plain next to it sustains farms which grow corn and potatoes, natural meadows, and beyond that woods with abundant deer, wild boar, peacocks, tigers and leopards.

Off the coast of Cap Saint-Jacques

A temperature cooled by the sea breeze and the fresh and crisp air of the forested mountains, along with the possibility of sea bathing on a fine sandy beach, make cap Saint-Jacques a sanitarium, a place of convalescence which is frequented in every season.

On the shore, in the shade of magnificent oil trees and slender palms, rises a pagoda of poor appearance, dedicated to the whale protector of the shipwrecked. It conserves the skeleton of one of those enormous cetaceans. The skeleton is covered piously with mats and topped with a large red star. Around this great debris, we may see several tombs containing the bones of small whales and porpoises.

Annamite and even Chinese sailors come here to do their prostrations to the accompaniment of gongs and firecrackers, hoping to secure a good wind and a favourable crossing. The Annamites claim that when they are shipwrecked, a whale or a dolphin will take them on its back and carry them safely to the shore. However, it is a fact that their junks are shaped like large fish. Eyes are painted on either side of the ship’s bows, and many vessels are also decorated with wooden appendages which mimic fins. Clinging to the hull of one of these vessels, upturned and being pushed by the tide towards land, it would be very easy to believe that you were being saved by a whale or a dolphin!

The sails of Annamite junks are triangular in shape and hang from the yard which is affixed to the main mast. The stays are made from rattan. The anchor is made of wood and consists of two connected parts, which makes it very durable. The flag is never fully hoisted and floats as if it were at half-mast. Junks usually have three masts which occupy less than half of the boat from the front and are aligned in order of size. Junks coming from Tonkin generally have square sails.

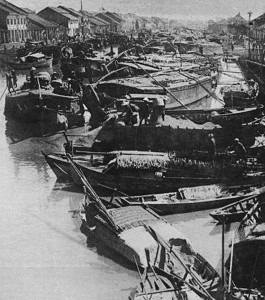

A Chinese freight barge

These junks cover considerable distances between Tonkin, Upper Cochinchina, Lower Cochinchina and Cambodia; the value of goods traded by them with Saigon alone amounts annually to over 13 million francs, and the number of junks coming in and out of Saigon every year exceeds ten thousand.

Arrival in Saigon

It has sometimes been argued that the location of Saigon, 60 nautical miles from the mouth of Donnai River, is a real obstacle to the prosperity of this port; that the delay thus caused to vessels which frequent it is a barrier to it becoming one of the great entrepots of the China seas and the commercial warehouse of these parts.

For these reasons, we will answer that ships using the China seas always pass the Poulo-Condor islands and often the cap Saint-Jacques lighthouse; that the electric telegraph established between that point and Saigon permits vessels in search of charter not to go up river unnecessarily; that almost all the rivers leading from that coastline come within reach of Saigon and are well-resourced in river boat as well as sea junk transportation; and that loading and unloading facilities and storage in Saigon are large and the port offers an excellent and safe anchorage in case of war.

Besides this, Saigon boasts the same benefits as many other ports of great importance located at the end of large rivers. Finally, it is the only port on the Gulf of Siam which offers so many facilities for trade and navigation.

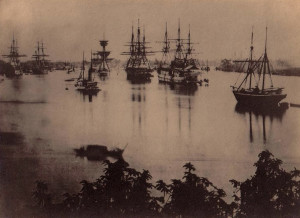

Ships on the Saigon River in 1868

The Donnai is a beautiful river which may be navigated by the largest ships. Its shores are flat and monotonous, and on the way up river we see only mangroves whose bare roots are constantly washed by the tide. Small snakes and crocodiles swim in the shallows. Occasionally, groups of monkeys play in isolated clumps of palm trees. Amidst the commercial junks appear tiny canoes, rowed by women or children using their feet.

Finally, after four or five hours of sailing, we arrive at the Fort du Sud, which is used as a military prison. We then enter the harbour, making our way past merchant vessels from many nations, including France, Britain, Prussia, Denmark and America. We’ve arrived in Saigon!

The painted wooden bell tower, before which we pass, is that of the first church built in Saigon. It was raised in 1861 through a subscription of officials and officers of the expeditionary force. The huts which are grouped along the shore form the village of the Bishop (village de l’Évêque); this is where, before our taking of Saigon, Monsignor Dominique Lefèbvre, Bishop of Isauropolis and Apostolic Vicar of Western Cochinchina, hid to evade capture by royal forces.

Along the quayside are moored huge Chinese junks, veritable Noah’s arcs, covered by palm leaf roofs, with eyes painted on their bows. On their aftcastles, dragons take flight against a background of a red moon. On festival days, these ancient sailing vessels resemble great Chinese pavilions, standing firm against the upstart steamships which are slowly but surely replacing them. Engaged exclusively in cabotage and travelling with the favourable monsoon, they carry three square sails made from cotton canvas. The stays are made from long, flexible rattan. They are armed with several guns for defence against the Chinese pirates who infest the Upper Cochinchina seaboard. To protect shipping from these pirates, our gunboats frequently patrol the coast.

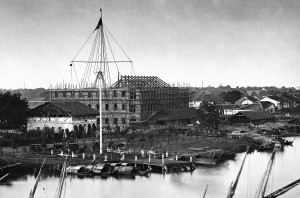

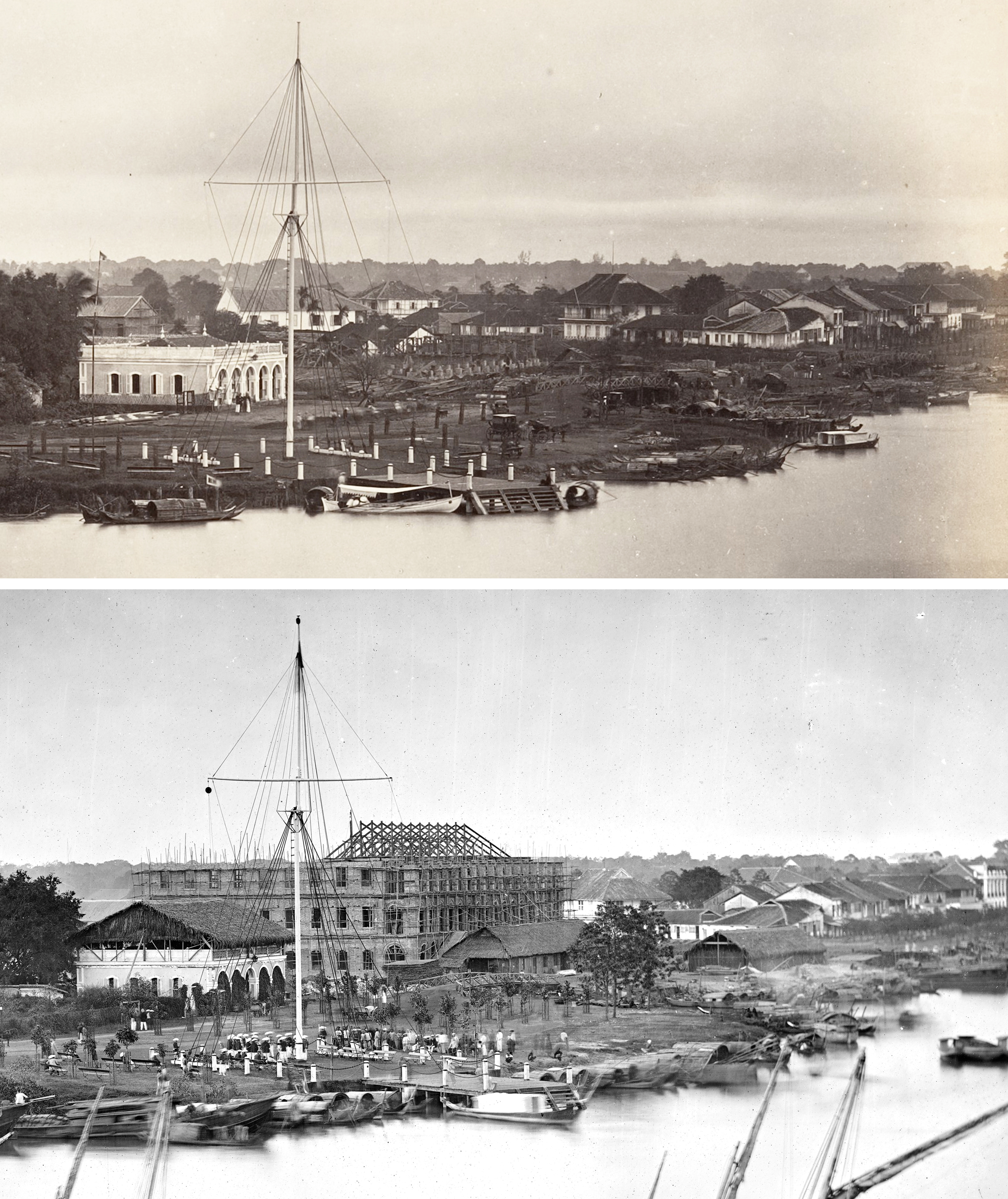

Saigon harbour in the early colonial period

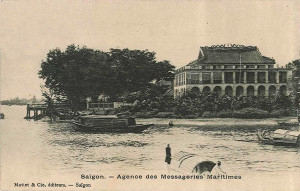

We are at the junction of the Saigon River and the arroyo-Chinois [Bến Nghé creek], in front of us are the institutions of the Messageries-impériales. On the headland opposite, usually known as the pointe Lejeune (named after the ship’s captain and senior commander of the navy who installed the Signal Mast), benches are arranged on the waterfront, and evening walkers are enjoying the fresh air and the animated appearance of harbour. At the tip of the pointe Lejeune stands the flagpole of the Signal Mast, and immediately behind it the Commercial Port Directorate, which is responsible for signalling to the entire city the impending arrival of warships, trading ships and courier vessels, as soon as they are announced by telegraph from cap Saint-Jacques. It is on this headland that all the beautiful people of Saigon meet at five o’clock every Monday and Friday evening to listen to music.

The courier ships of the Messageries-impériales anchor directly in front of that company’s Directorial residence and office, abeam from the rue Catinat and a small pyramid raised by commercial interests to the memory of Lieutenant Lamaille, who was once responsible for European Affairs in Saigon. On the other side of the river we may see the village of Thu-Thiem, founded by Catholic Annamites who chose to follow us when we abandoned Tourane. Along the shoreline throng many small boats and canoes. Many families live right here on the water, sleeping and cooking inside their boats; small children swing in hammocks suspended from the roofs of the boats. At night, these houseboats are lit by oil lamps, and the riverbanks are illuminated by a thousand specks of light. Also lining the riverbanks are mandarin junks decorated with umbrellas, peacock feathers and bells, sampans installed by Europeans for their use, and rows of commercial junks with their bows painted in a uniform manner, indicating a common place of origin.

The Messageries maritimes (formerly Messageries impériales) wharf in the 1870s

Further along the river we pass the coal depot. Then, as we enter the port of war, we encounter a row of large seagoing vessels lined up along the riverbank. The flagship Duperré, residence of the commander of the French navy; the transport ship Meurthe, which has been transformed into a workshop and forge; the frigates Didon and Persévérante; and numerous dispatch boats, gunboats and launches.

A little further north along the river, the iron floating dock spreads its broad flanks. It was launched in May 1866 under the direction of Captain Lejeune, and has functioned quite satisfactorily ever since. To date it has been used to overhaul the frigate Persévérante and the transport ships Orne and Sarthe, as well as several other large vessels. Its construction lasted from January 1864 to May 1866. It is 91.44m long by 21.33m wide at its entrance and 13.71 wide at its closed end.

Opposite the floating dock is a 72m long by 24m wide dry dock for large gunboats and cruisers with a water draft of up to 4 metres. For small gunboats there are two other small dry docks. The construction of a larger dry dock in masonry is now being planned and will probably be undertaken in the near future.

Along the banks lies the Naval Arsenal with its provisions stores and naval construction workshops.

The appearance of the city can be very different, depending on whether one arrives in the harbour by day or by night. When arriving by day and passing the Messageries-impériales, one notices that the houses around it are fewer in number; here, the city is still in the process of formation.

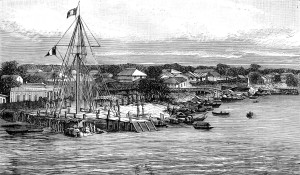

The Signal Mast and quayside in the mid 1860s

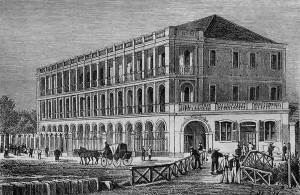

Beyond the pointe Lejeune, however, the quayside features some remarkable buildings – the great Hôtel Wang-Tai, the Cercle du commerce, a Buddhist pagoda.

The construction of the quays continues slowly. It is true that Saigon does not have all the resources of the Metropole, and even Paris itself was not built in one day. A guard room is ungracefully planted at the edge of the water. Further along there opens up a big empty space which is currently being transformed into a roundabout, or perhaps a square, where some benches have been placed in anticipation.

When you arrive in the harbour at night time, the large number of lights which line the river give a much more favourable idea of the city.

Entering the city

As soon as a ship enters the harbour of Saigon, it is accosted by a host of small sampans. The traveller selects one, gets the porter to place his luggage aboard, and then relaxes under the straw canopy which gives protection from sun or rain as the sampan takes him across the harbour.

These small boats have no rudder, and the rower, who is standing, steers with his or her oar. Only one or two people can travel comfortably in a sampan. In the daytime the price of a journey across the harbour is at least 20 cents, excluding the cost of baggage. At night time, the same journey can cost at least 30 cents plus baggage charges. Teams of Chinese or Annamite porters stand by at the quayside awaiting the arrival of the luggage, which they will then carry into the city using ropes and bamboo frames. As for lighter objects, a young Annamite will often convey these in a basket on his head, hence the name “paniers” which we give to these young men.

The Maison Wang-Tai

If you prefer to be severely jolted, you may find, next to the Messageries wharf, carriages similar to those known in Singapore as palanquins. These noisy and stiflingly hot little boxes on wheels, drawn by tiny and feeble horses, are led by an Indian groom who runs next to the horse holding the bridle and whipping it into action. The price of these carriages is 2 francs for the first hour, 1.50 francs for a single journey, and 1.50 piastres or 9 francs for a whole day.

There are in Saigon several hotels on the quayside and on the rue Catinat [Đồng Khởi], but none have particularly desirable facilities. One is generally served table d’hôte. A restaurant has also been established on the quayside; lunches cost 1 piastre, dinners 1.25 piastres, including wine.

The currency in general usage in Cochinchina is the Mexican piastre, which has a weight of 26.94 grammes, and a value which varies from 5.37-6.30 francs, according to the exchange rate. The current official rate set by the government is 5.55 francs. Although they were greatly valued in former times, piastres marked in China (chop dollars) may now be exchanged only at a considerable loss in Saigon, mainly because of counterfeiting. These days, many Chinese compradors are as adept at discovering counterfeits as their compatriots are adept at making them.

The piastre is divided into cents (pronounced cints), the cent being a nominal division in Cochinchina which effectively corresponds to the English cent used in English territories.

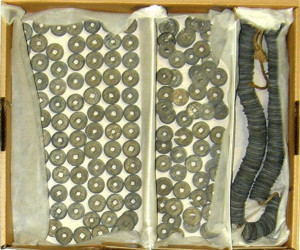

In the early colonial period, the Mexican piastre was the currency in general usage in Cochinchina

In many commercial transactions, the Annamites use silver bars worth 16-18 piastres each. This is a rectangular ingot, one face of which is concave and the other convex. It is worth between 80 and 100 francs. Annamite ingots below or above this value are very rare, and remain in the hands of the Annamite government. Gold enters very little into circulation.

The French 5 franc silver coin is not in favour. You will lose a lot when you try to change French silver coins for sapeques. Thus, the Annamites only evaluate the franc as being worth 8 tiens of sapeques or 80 centimes, the tien being of 10 cents, while in contrast the piastre attracts quite a favourable exchange.

The Chinese sapeque known as the li is used in gambling houses, but in Cochinchina it is not used in any other transactions. 1000 li = 1 liang = 1 silver taël = 7.50 francs. It is only mentioned here because we often speak of it in cases involving trade with China.

The Annamite sapeque is a zinc disk pierced in the centre with a square hole, and bearing on one side the figure of the reigning monarch under which the coin was minted. Six hundred of these discs strung together form a ligature (quan tien) or a chapelet worth 1 franc. Each ligature is divided into 10 tiens of 60 copper coins each. The assembly of 10 ligatures – a currency worthy of Lycurgus of Sparta – is heavy and difficult to carry around. The adjudication of the provision of sapeques in Annamite territory is made by number and not by weight, in accordance with the old adage Non ponderantur sed numerantur, but the coins themselves are manufactured poorly using a very brittle alloy. As a result, the ligatures often break and the coins get damaged during transportation, forcing us to suffer considerable losses.

A ligature of Annamite sapeques (photo http://webmuseo.com/)

In recent years, sapeques have become more rare, but the Annamites here still prefer them to copper and silver money, especially in the markets of the interior. For those who earn and spend little, the sapeque is of great benefit. They can obtain things worth less than a centime, or pay by the half, quarter or even sixth of a centime for areca nut, betel leaves, tobacco, cigarettes, a cup of tea, a slice of pineapple, an orange, a jackfruit, a fragment of sugar cane, a spoonful of fish sauce, or a palm leaf hat. Nonetheless, the introduction of French coins has been essential for the European population, which could not subject itself to the use of sapeques in everyday purchases or payments.

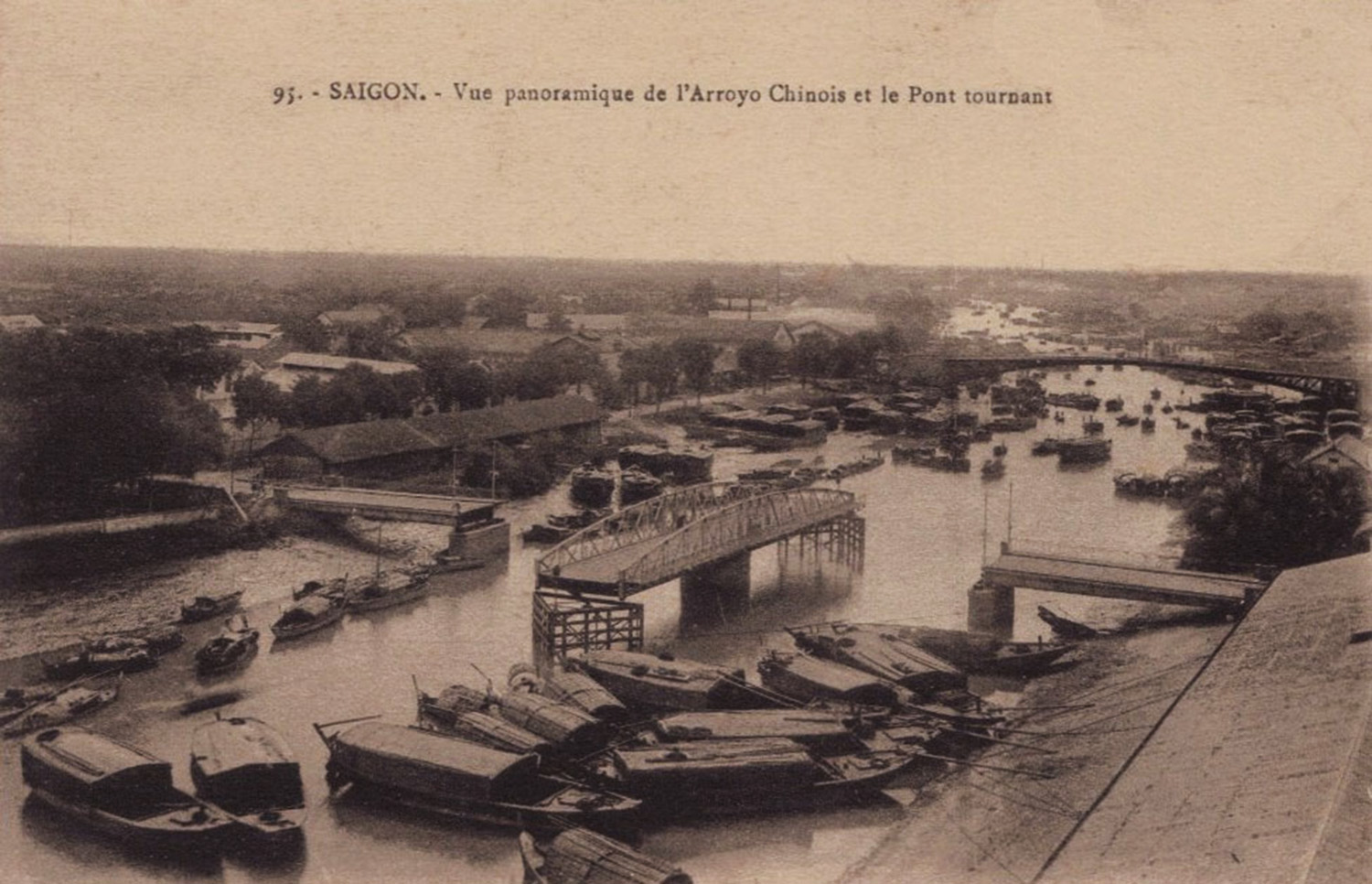

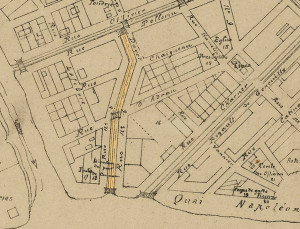

The city of Saigon is enclosed in a square formed by the Saigon River to the east, the arroyo Chinois to the south, the arroyo de l’Avalanche to the north and the canal de Ceinture (Belt Canal) which connects the two arroyos to the west. “Saigon” was the name given by the Annamites to the Chinese market which one now calls Cholon, and which was established on the banks of the Ben-Nghe (arroyo Chinois).

The French have improperly applied the name to the current Saigon, which the Annamites designated by the names Ben-Nghe or Ben-Thanh, according to whether they were referring to the part neighbouring the arroyo Chinois (rach Ben-Nghe), or the portion adjacent and below the arroyo de l’Avalanche, where the old citadel is located (Thanh).

The rue Catinat, situated in roughly the mid point of town, runs from the Saigon River up to the place du Gouvernement [modern Cathedral square].

Before reaching the place du Gouvernement, the rue Catinat brings us to the boulevard du Gouverneur [Lý Tự Trọng], a big and beautiful thoroughfare which was created by the administration of Admiral de la Grandière. Raised over the broad marshy moat which once defended the former citadel, it is planted with tamarind trees.

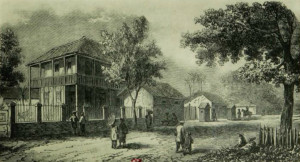

The first Governor’s Palace

Arriving at the place du Gouvernement, we see a heavy and unsightly square pyramid which hides a masterwork of interior carpentry; this is the Clock Tower, which gives this square its alternative name, place de l’Horloge. Around the square are grouped: the Directorate of the Interior, the Telegraph Office, the Treasury and Post Office, the residence of the Chief Commissioner, the Commandant of Troops, the dependencies of the Governor’s Palace, the Hydrography Office and the Observatory.

On 23 February 1868, Admiral Governor and Commander in Chief M. de la Grandière, solemnly laid the first stone of the new Palace of the Government [later the Norodom Palace], which is located nearby, at the junction where the rue de l’Impératrice [Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa] meets the road to the Chinese city.

It was to the Marine Engineering Corps that we entrusted the implementation of these major projects – creating new streets and levelling the plateau for water flow and sanitation, as well as widening the small canal which runs parallel to the boulevard du Gouverneur, connecting the arroyo Chinois with the arroyo de l’Avalanche [Thị Nghe creek] and receiving the waters of the upper plateau while draining the shallows it travels through. This goal having been achieved, it would now be desirable for this canal to be filled, or even dug deeper. In any case, that can only come after first dealing with the Grand Canal [now Nguyễn Huễ boulevard], that great artery running perpendicular to the Saigon River, a station for the boats which supply the market, where the tide rises twice each day. This is an important shipping basin, the dredging of which has great importance for local residents and traders.

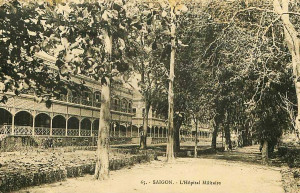

The Military (later Grall) Hospital

Following the boulevard du Gouverneur, we pass the Military Hospital. It has been said that, to found a colony, the English begin with a stock exchange, the Spanish with a church, and the French a café. However, the first establishment in Saigon was not a café, but a hospital for the sick and wounded of the expeditionary force!

This fine institution, with its large and airy rooms and well-chosen location, was established even before Admiral Bonard had been properly lodged. The Singapore newspaper Free Press (February 1869, Volume 1) reported as follows in 1861:

“Despite the proximity of the enemy, the French have succeeded, spade and trowel in one hand and sword or rifle in the other, to build hospitals for several hundred patients, and to create several miles of excellent roads. All of these constructions have since been completed, and the Saigon hospital has been sufficient to meet the most pressing of needs. Rooms are reserved for sick officers, and the governor also authorises the admission of civilians at their own expense.”

At around the same time, Monsignor Lefèbvre, Bishop of Isauropolis, set up an Annamite hospital, which the government has since taken charge of and established on a broader basis. This establishment costs the colony nearly 48,000 francs each year.

The European cemetery is located near the village of Phu-Hoa, on the road leading to the third pont de l’Avalanche [Third Avalanche Bridge, now the Kiệu Bridge in Phú Nhuận].

The Sainte-Enfance (Holy Childhood) orphanage in the 1860s

The officers and soldiers of Spain, who left in the colony such brilliant memories of valour and courtesy, built a large wooden barracks, next to which they laid the rue Isabelle II [now Lê Thánh Tôn street], one of the first, longest and most beautiful streets of Saigon. They also built a brick gunpowder store near the present Telegraph Office, but this has recently been removed.

The boulevard du Gouverneur leads us directly to the Sainte-Enfance (Holy Childhood) orphanage, which is housed in a building of mixed style flanked by a Gothic chapel, ornamented in accordance with Annamite taste and built by an Annamite architect. Its graceful bell tower may be seen from afar. The administration has created 100 scholarships for young girls to be raised and educated in the Sainte-Enfance by the Sisters of Saint-Paul of Chartres.

Nearby is the Collège d’Adran, run by the Frères de la Doctrine chrétienne, which renders great service by teaching French to young Annamite students and instructing them in the most common applications of science, art and industry. The college is named in memory of the illustrious Bishop of Adran. The administration has also created another 100 scholarships to enable young Annamites, sons of government officials and others who may be recommended for their honesty and dedication to France, to study here. Orphans, and other children whose intelligence promises good results, are admitted irrespective of religion.

The Collége des interprètes français (College of French interpreters) is headed by a very distinguished Annamite, Mr Petrus Truong-Vinh-Ky; Ten aspiring French interpreters are currently studying the Annamite language, and after passing an examination they will be employed as interpreters. This college is part of the municipal institution of Saigon.

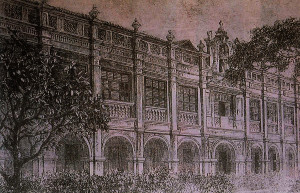

The Saint Joseph Seminary of the Mission in the 1860s

The Seminary of the Mission is a little further up the road. Here, the French language is taught to students in higher classes; This property has a beautiful facade which strikes the eye. It is surrounded by a large garden and located on raised ground. From this location, one may see the harbour, and behind it the Thu-Thiem plain and the mountains of Bien-Hoa and of Cau-Thi-Vay.

In front of the Seminary is a convent of European and indigenous Carmelites. We do not know why these nuns, who live a completely cloistered life in France, were called to Cochinchina to undergo in perpetuity the same rigorous imprisonment in a climate which is more annoying by far.

On top of the plateau is the ancient Annamite citadel, whose fortifications have been restored. The general government stores where the annual exhibition is held are located close to the arroyo de l’Avalanche. On the banks of this creek is the Botanical and Zoological Garden. Already this garden has been generously denuded of many of its riches for the benefit of France.

The Botanical and Zoological Garden contains installed enclosures where rare animals and birds enjoy a semblance of freedom. This arrangement not only facilitates study through observation, but also avoids the repulsive appearance of city museums of skeletons and mummies, which only offer a tolerable view of stuffed birds. The acclimatisation gardens for animals and plants represent great progress which will benefit both animals and people. I am surprised that this improvement was never proposed by the good Lafontaine, who knew so well how to talk to animals.

Saigon Botanical and Zoological Garden

Going downhill again, we pass by the Directorate and other establishments of the Artillery.

The Infantry Barracks are located at the top of the rue Impériale [Hai Bà Trưng]; an Annamite army camp is located on one side of it and the Camp of the Literati on the other.

On the right bank of the Grand Canal stands the Cathedral. The bishopric is situated between the rue d’Adran and the rue de l’Impératrice.

Next to the Grand Canal extends the well stocked City Market, where fresh vegetables may be bought at all times. Here you may have sausages made in front of your eyes by a butcher, or sweet treats made by a confectioner. Or if you prefer, an old Annamite will serve you with delicious pancakes and rice with pistachios, sprinkled with brown sugar. Around the corner are the moneychangers with their piles of currencies and their heavy ligatures of sapeques. Inside the halls are long lines of market stalls which offer the most varied selection of goods of Annamite, Chinese or European provenance, giving wide choice to the shoppers who clutter the aisles.

The municipal office or City Hall is located midway along the rue Catinat. Council members are selected from all classes of society and from all nationalities, both Asian and European.

There is in Saigon a Commissaire de police in each of the city’s two districts. The city police (giam thanh) is made up of European gendarmerie, Malabar police guards and Annamite police guards, the latter known as matas. Furthermore, military patrols take place every night and military posts are located all around the city.

The new Palace of the Government (later the Norodom Palace) nears completion in 1871

Despite all of the above, many works in the new town of Saigon and in the provinces remain in progress or yet to be implemented. In particular, the completion of the street layout, the installation of bridges, and the construction of civic buildings such as the Palace of the Government, the Law Courts and the future Town Hall, offer many potential items to the industry of Europeans.

One may find views of the city and surrounding areas, along with images of the indigenous people, at photographer’s shops in Saigon. A city map has also been drawn by the administration of roads and bridges.

Excursions around Saigon

The most interesting excursion which can be made around the city is undoubtedly the journey to Cholon, the Chinese city, which is located 5 kilometres from Saigon. You can visit either by boat along the arroyo Chinois, priced at 2 to 3 francs each way, or by carriage, priced at 8 francs return, with a stay of an hour at most, or 12 francs for the day. The route Stratégique through the plaine des Tombeaux (Plain of Tombs) is rarely used; rather, one takes the route des Mares or alternatively the “Low Road” along the arroyo Chinois. The route des Mares runs from the place de l’Horloge, past the Directorate of the Interior, the Prosecutor’s residence, the Gendarmerie and the Prison. It is lined with European villas and ancient Annamite gardens planted with grapefruit, curious banyan, beautiful tamarind and graceful areca.

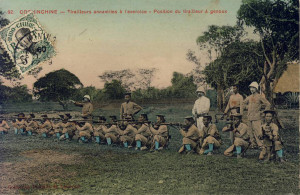

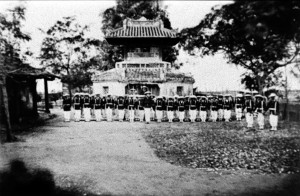

Training of local riflemen at the Camp des mares

The road runs past the Stud and the artillery park known as the Camp des mares (Camp of the ponds), because of the two ponds which may be seen either side of the main gate. The local mandarins keep fish in one of the ponds, and crocodiles in the other.

The camp stands on the site of a former royal pagoda which was intended to perpetuate the memory of the illustrious men of the country, and we remember seeing there a large number of small tablets, each bearing an inscription in gold lettering. Here was written the name of a French sailor named Manuel, who had given his life for the cause of defending Nguyen-Anh (Gia Long) in the war against the Tay-Son, or “montagnards of the west.” As in ancient Rome, the souls of illustrious citizens are regarded by the Annamites as protective deities.

Here’s what the Gia Dinh Thong-chi said about this subject:

“In 1783 at Can-Gio (at the mouth of the Saigon River), the Tay-Son rebels, after invading Gia-Dinh (province of Saigon) and having the flood and wind on their side, fought a battle with French Captain Manoé, and despite great resistance on his part, set fire to his ship. This brave officer was killed in action. After his death, he received from the King of Annam the title ‘Faithful Subject, Just and Deserving, Great General and Pillar of the Empire.’ The tablet was placed in the Mieu-Cong-Than or Temple of Meritorious Officials. These titles were engraved in gold letters. This Manoé was a simple Breton sailor, very brave and very intelligent.”

In another temple, closer to Saigon, Gia Long married a woman who became the mother of King Minh-Mang.

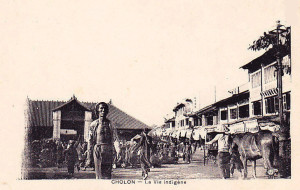

The road from Saigon to Chợ Lớn

We pass on our left the pretty village of Choquan, and to our right the Plain of Tombs, and soon we are in Cholon. We pass the Finance Department, the Prefectural Government Office and the Telegraph Office, the Infantry Barracks, and many pagodas, including the Pagoda of the Warlike Deities. We enter for a moment through its left door, and we see the shrine, decorated, besides the usual ornaments, with brocaded silk and gold banners and swords, spears and halbards in painted wood.

Two bulging guards stand opposite each other, one with a black face, lance in hand, the other with his hands hidden beneath wide sleeves, and both with long moustaches and beards which hang below the ears. On the main altar is a white-bearded god holding in his hand a bow and arrows. This is probably Kuang-Ti, the Chinese Mars; his son Ping Kuang and his faithful squire are at his side (Le P. Huc speaks at length about this Chinese deity in his work l’Empire chinois, Volume 1).

We visit the Kwan Chin Hway-Quan temple, which was raised by the Chinese of Canton to the goddess Koang-Yin, or Apho, the creative power, the mother deity of the Chinese of Guangdong, the patron saint of sailors, the Chinese Amphitrite. We cross a paved granite courtyard made from flagstones brought from Canton. Two granite sphinxes rolling a ball between their teeth guard the entrance. Along the walls we noticed floral decoration with a very good finish, although we have rightly criticised the Chinese for making only rough work in this genre.

Above, we see characters depicted in various scenes. These are ceramic figurines, covered with enamel colours and shimmering with many small reflective surfaces, colourful gouaches, big red lanterns, a carved and gilded Panka, and on the roof snakes and fantastic birds fashioned from glazed ceramics.

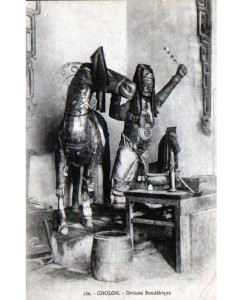

A deity in a Chinese assembly hall

The doors are carved in the very latest style; on either side of them is a small altar where a bearded god is seated. Along the side galleries, black marble plaques embedded in the wall are covered with inscriptions. Above them are gouache paintings and bas relief sculptures representing battles on horseback with spears, bows and axes, mandarins holding audience and ladies of the royal court.

A square space between the front and main halls is reserved for setting off firecrackers. Gold and silver votive papers are burned in a large cast iron ornamented urn which is placed in front of the altar. This space is separated from the other halls by framed archways made from beautiful hardwood, and on their pillars are hung twin sentences in gold. Here are placed chairs, settees and small tables in black wood with marble tops.

The main hall is situated beneath a large canopy supported by elegant pillars; the shrines are large niches containing carved, lacquered and gilded altars. This is where the Chinese deities are enthroned; the goddess herself occupies the central space, flanked by menacing bearded supporters.

The goddess wears a crown topped by a red square, and her hairstyle resembles that favoured by Italian women. She also sports earrings, and around her head she has a golden halo. She holds in her hand a golden flat rule, similar to that used by the great mandarins. Either side of her are the shrines to two other goddess.

In front of these shrines we see large screens made from peacock feathers, triangular flags, a model junk with sails, joss sticks, fake flowers and lotus buds and boards bearing inscriptions. On feast days, the shrines are also decorated with the banners of the Cantonese congregation, and on a large table is placed a cylinder wrapped in sandalwood or other fragrant wood, a great prize to be burned in the temple.

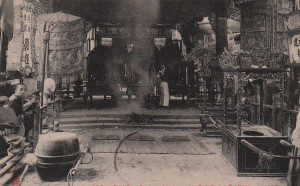

An interior view of a Chinese assembly hall

On one side of the main hall is a drum, while on the other is a beautiful bell. Three tables are carefully arranged in front of the shrines to receive the offerings of sacrifices, which consist of glazed roasted pig, fruit, cakes, poultry, seafood and tea. Beneath these tables are mats and cushions to help the worshippers make their prostrations and offerings against the deafening background noise of drumbeats, bell tolls and detonations of firecrackers.

In this temple they consult spells using a curved bamboo root split into two. They compare the two parts, then drop them so that they separate. The way in which the strands of each half fall is then deemed a favourable or unfavourable prognosis. Alternatively, they randomly throw 49 small sticks on which predictions have been written; if their fortuitous position on landing corresponds to the lines indicated in the books of the monks, it is deemed a happy lot. On holidays, monks preside over the ceremonies, and in the morning the Chinese come in full dress to make their adorations.

On the right side of the temple is a stereotyping workshop which reproduces prayer sheets. The characters are engraved on wooden boards, and a considerable number of copies made. This method is not as advanced as that of the Buddhists, who sent to our 1867 exhibition a prayer sheet machine which produces 120 copies per day.

Nearby is a room where they make and sell candles, golden and silver votive papers, bundles of fake copper coins and paper piastres, ingenious bank notes within the reach of every budget. The good Chinese burn them together with replicas of clothing and other necessary objects of material life to give to those already enjoying the afterlife, all of them represented in coarse paper and disappearing quickly up in smoke.

Another interior view of a Chinese assembly hall

Another compartment contains four large cauldrons and is used for cooking on festival days. We have seen large tables heaving with piles of roasted pigs which are offered as sacrifices for the benefit of the living, who talk and laugh loudly, coming and going within the precincts of the temple. A Chinese orchestra mingles its discordant notes to this cacophany.

In the side compartment to the left of the temple is a room whose walls are decorated with black ink drawings. Equipped with a table and two beautiful chairs, this is the office of the temple.

There are also other shrines, and a kind of attic which is reached via a wooden staircase, but one sees nothing remarkable there.

The city of Cholon consists of 10,600 Chinese and 32,000 Annamites; there is also a floating population of around 8,000 individuals, giving an approximate total of 50,000 souls. The per capita tax for Chinese and Asians is 2 piastres (11.10 francs), and for the Minh-Huong (Chinese-Annamite mixed race), 1.50 piastres or 8.32 francs.

The Chinese usually marry Annamite women. They have lovely children who remain Annamites and form a very intelligent class. These mixed-race Minh-Huong are generally rich and have their own congregation.

A soup seller in Chợ Lớn

The Chinese traders here always ensure a comfortable future for their wives, either before their death or before they return to China. In our Cochinchina possession, we need not fear the ramifications of the great disproportion in the number of men and women which afflicts the Chinese communities in Singapore, Melbourne, etc.

The city of Cholon has been divided into five districts, each with a Chinese leader, a Minh-Huong leader and an Annamite leader, which has had the effect of making uniform the three population components and involving the Annamites, despite their apathy and distrust, in local improvements and the commercial development of the city.

The Inspector of Native Affairs is responsible for the administration, supervision and control of the indigenous leaders and leaders of the Chinese congregations. He is also in charge of justice and tax collection.

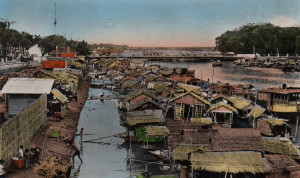

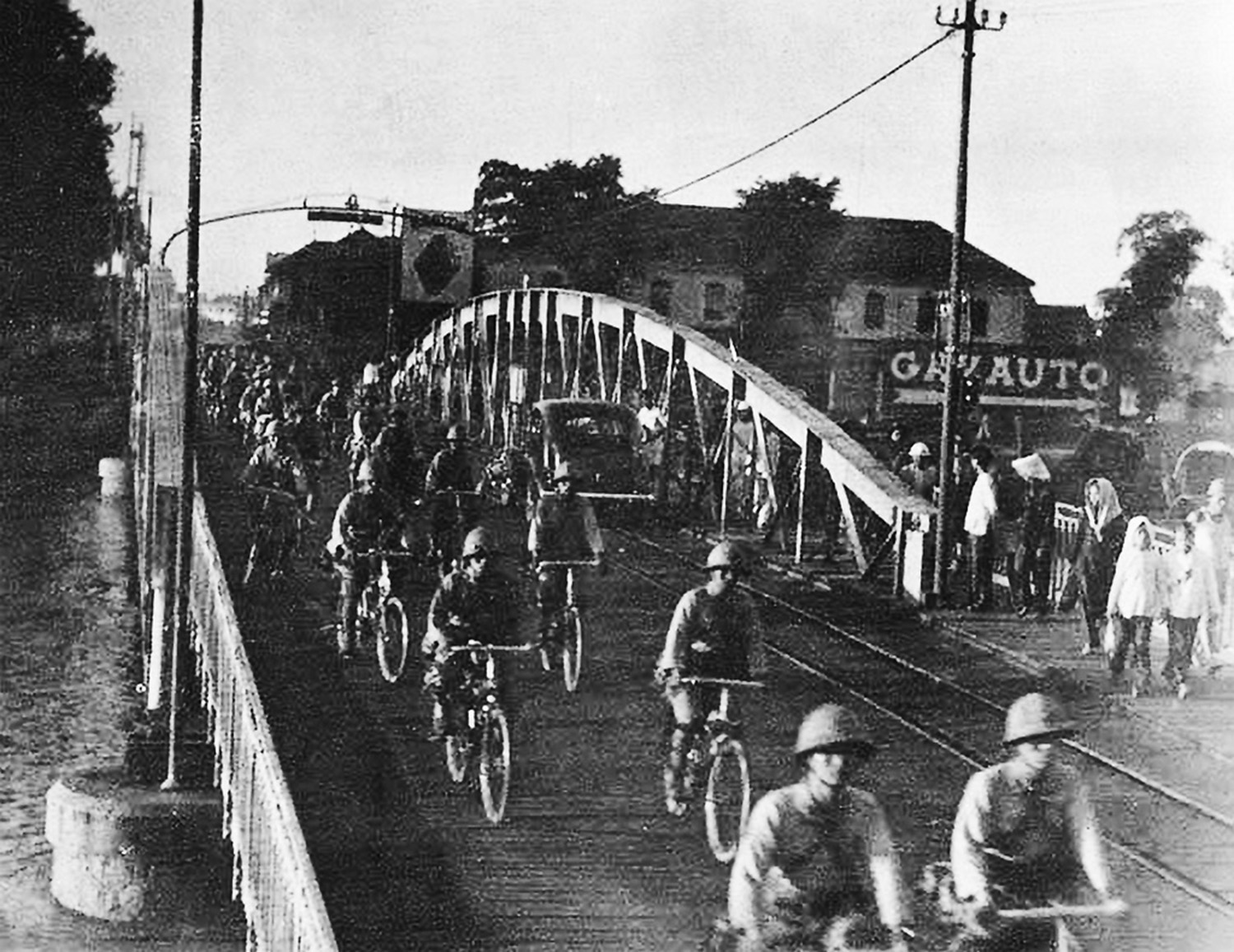

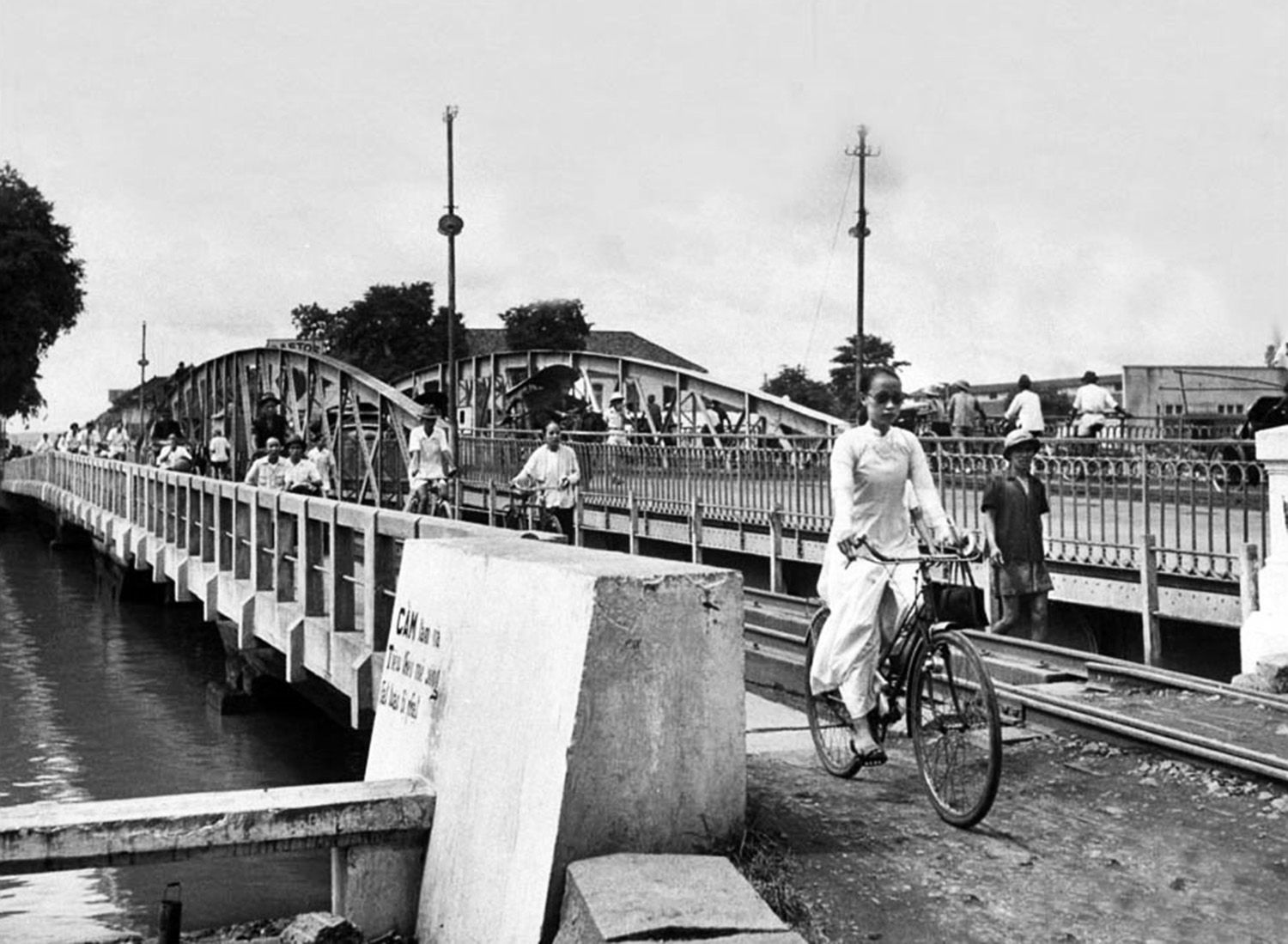

When we first arrived in Cochinchina, Cholon was a dirty city with long, narrow and winding streets, lined with dark and unhealthy houses. The tiny bridges across the creeks and canals were impassable to carriages and inconvenient for European pedestrians, and many streets were flooded at high tide.

A few years of extensive work, deftly directed, has completely changed the appearance of the city. Wide streets have been created, quays developed, canals dug, houses on the waterside reconstructed or restored, strong bridges built, streets lit, and properties demarcated and guaranteed by securities. Annamite villages have been moved to new sites, and now we may walk at ease in this thriving city.

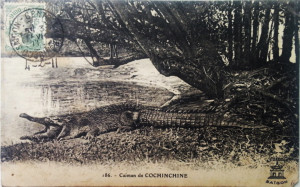

Chợ Lớn once had a crocodile farm

We pass an undertaker’s store. The catafalque standing outside is decorated with gilding and inlays, and it will take 20 or 30 men to carry it. Small children play in a coffin which awaits an occupant. This store is filled with imposing pieces of furniture which will be the last resting places for many wealthy merchants.

Next door to the undertaker is a merchant of trinkets who sells false hair; because if coquetry has been lost in France, we may still find it here in Cochinchina.

Further along the road, we find a pharmacist, a barber, and under an awning, a pastry confectioner. Then a gambling house, a dying workshop, an opium den, a goldsmith’s shop, and a large store selling manufactured goods in Europe.

Cholon also has a crocodile park. The Annamites are very fond of the flesh of the saurian, which abounds in the arroyos of Cochinchina. In 1865 alone, more than 500 crocodiles from the great Cambodia River were consumed here in Cholon.

The Cholon City Market, currently a temporary structure, is very animated. On the waterfront nearby are rows of major Chinese trading houses and warehouses containing rice, sugar, indigo, wax, silk, porcelain, pottery, dried fish, cotton, peanuts, and the hides of buffalo, oxen, snakes and tigers. At their entrances, clerks and porters congregate around sets of weighing scales and bales of goods of all shapes and sizes.

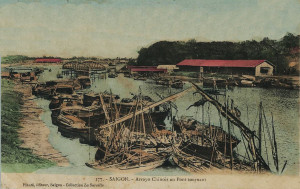

Merchant vessels on the arroyo-Chinois

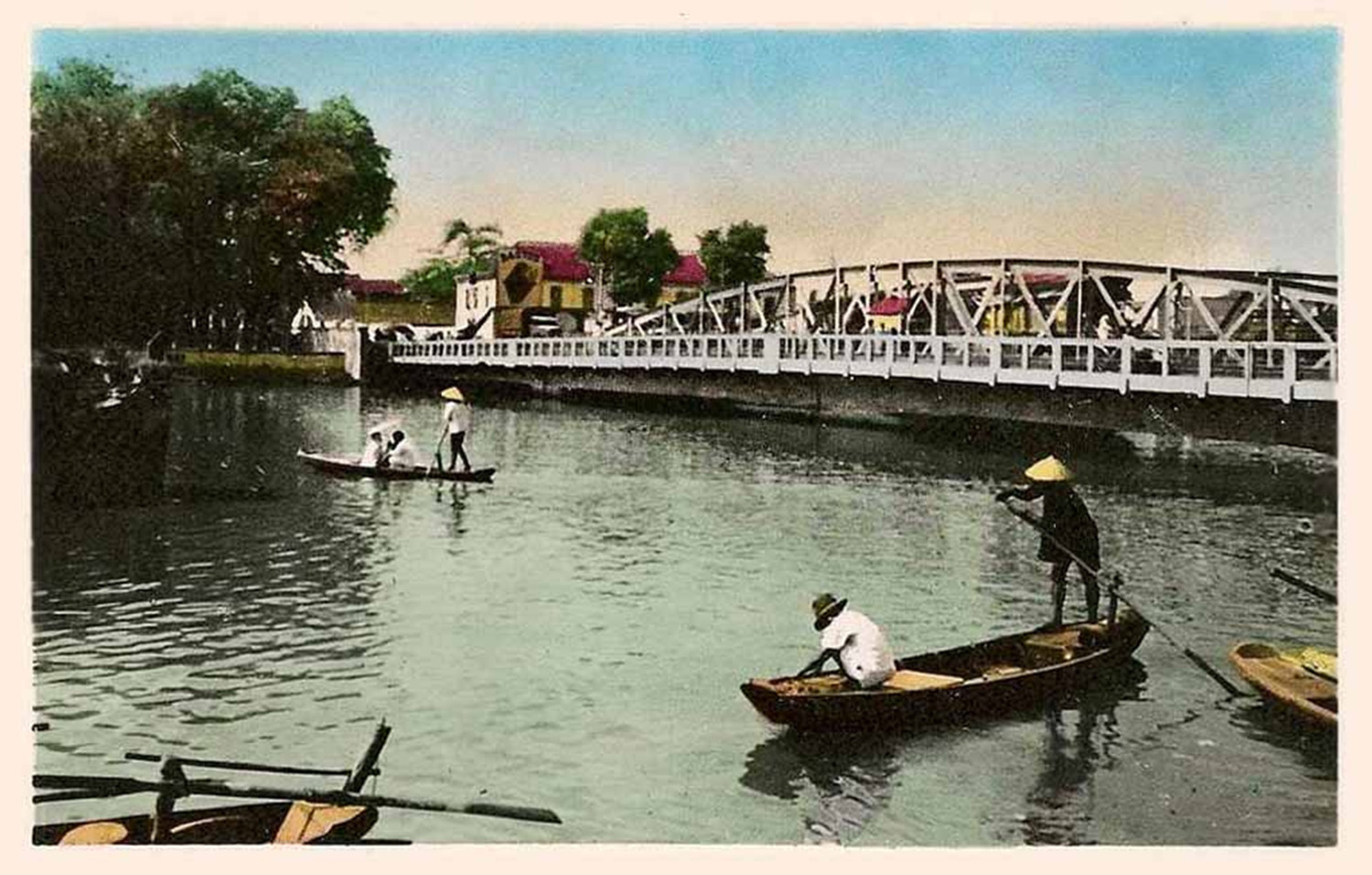

The arroyo (a Spanish word meaning river, in Annamite rach) of Logom and various other waterways bring the junks to the foot of these stores and permit them to travel throughout the city. Junks, sampans and fishing boats throng these creeks and canals. Some of the boats contain reservoirs for carrying live fish to the market.

The arroyo-Chinois, which was dug in 1820, is a major artery which connects Cholon to the Saigon River on the one hand and the Cambodia River in Mytho on the other. This arroyo, on which the whistle of steam barges may be heard all day long, has ramifications throughout the country. Thanks to the traffic which travels ceaselessly along it, the tireless activity and financial resources of the Chinese, and the improved methods, initiative and industry of the Europeans, the prosperity of this city can only continue to grow in future.

Cholon is the storehouse of Cochinchina, Tonkin and Cambodia. It is from here that goods and commodities are shipped to Singapore, Hong Kong, Batavia and Bangkok. Nothing is more vibrant than the landscape of waterborne commerce which may be enjoyed while standing on the pont du Jaccaréo. From there one may witness the coming and going of junks, sampans and canoes against a backdrop of greenery which surrounds the post of Cay-May; and the porters, shop clerks and small merchants who hurry around the quaysides. Together they form a very interesting ensemble which would give anyone doubting the future of Cochinchina cause for reflection.

The French schools founded by Admiral de la Grandière have achieved such excellent results, and are appreciated so much by the local people, that not content to send a significant number of their children to these schools, many Chinese leaders now want to learn themselves – if not the French tongue, then at least how to transform Chinese writing into European characters. The main school is run by the Frères de la Doctrine chrétienne (Brothers of Christian Doctrine).

The main city market in Chợ Lớn in the late 19th century

There are in Cholon eight Chinese congregations. The heads of these congregations are responsible for ensuring that all of their members are good citizens and work hard to develop a strong economy

The first Chinese emigrants who came here towards the end of the 17th century were Cantonese, and they settled partly in Bien Hoa, partly in Mytho, which were Cambodian provinces at that time. This first wave of emigration was followed by several others from Fukien and other Chinese provinces.

Their advanced civilisation and trade, their spirit of association, and later the religion, customs and writing which they shared with the Annamite conquerors of Cochinchina, gave them an important foothold in the country. As a result of the war between the Tay-Son rebels and Gia-Long King of Annam, they left their original settlements and came to settle in Cholon in around 1778. Despite the fact that in 1783 the leader of Tay-Son massacred more 10,000 Chinese and looted their business houses, despite nine months of a terrible famine in 1802, and despite the ban on export products in the country, the Chinese persevered and eventually overcame all obstacles, so that by 1830 Cholon was a very important market town, known to the Chinese as Tai-ngon, and to the Annamites as Sai-gon.

Today, the Chinese city is designated only by its Annamite name of Cholon, meaning big market (cho-lon).

Cây Mai Pagoda and fortress in 1866

A quarter of an hour from Cholon, on the road to Mytho, is the post of Cay-Mai. An avenue of acacias leads us to the foot of an artificial mountain in a delightful location with a small stream which flows down a stone staircase. A three-entrance gate with a large central arch gives access to the fort, and one finds there on top of the mound an octagonal shaped pagoda with a tower, flanked by palms and sacred cay-may trees. The latter is a type of plum tree with fragrant flowers, which it was once forbidden to touch on pain of death. These flowers were offered to the emperor and used to flavor his tea.

Monks guard the pagoda and the sacred plum trees. This place was once the destination of many pilgrimages. The great mandarin Trinh-Hoai-Duc, provincial governor of Cholon and author of the Gia-Dinh-thong-chi, gives us a lovely description. It is a model of Annamite prose:

“This hill stands like a kind of peak. It is planted with many southern plum (cay-mai) trees whose old trunks intertwine obliquely with each other. These trees flower during the winter and their leaves spread an aromatic odour.

The cay-mai flowers are in communication with the spirits of the air, which make them open. It is not possible to transplant these trees elsewhere.

At the top of the hill is located a pagoda. It is there, in the middle of the night, that prayers written on the leaves of trees are sung to the Buddha. The bell rings, and a voice rises like smoke rising up among the clouds. A crystal clear moat surrounds the hill, and small boats go there to pluck lily flowers. Girls prepare rice for the good people of the area, and in the evening they go to worship at the pagoda. On festival days, we see mandarins with bachelor and doctorate degrees processing up the ten steps of the temple, a bowl in one hand, a bundle of betel in the other. They sing poetic songs and, sitting on the summit of the hill with flowers their feet, their poetry is lost like incense, as they experience true joy at the sight of such a beautiful place.

A corner of Chợ Lớn in the early colonial period

This pagoda is established on the foundations of an ancient Cambodian pagoda. In 1816, the monks of the pagoda uncovered its ruins and restored it completely. Digging in the grounds, they found a very large number of bricks and antique tiles. They also discovered two long sheets of gold, each longer than a thumb and weighing as much as three sapeques. On each of these sheets was engraved the image of the Buddha, seated on an elephant. These sheets undoubtedly came from the ancient Cambodian pagoda.”

From this location, the view extends over the rice fields bordering the commercial arroyo, the Plain of Tombs, the former Lignes de Ky-hoa battlefield and the fields and woods of Go-Vap, all the way to the Tay-Ninh mountain, a distance of about 30 leagues. Cay-Mai was formerly a Cambodian fort, and at the time of the arrival of the French, the Annamites were occupying it with a detachment of Cambodian soldiers from the southern provinces. However, they subsequently deserted.

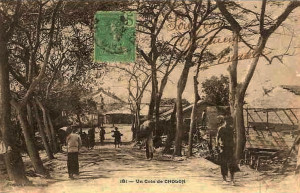

We return to Cholon by the road which runs alongside the arroyo-Chinois. On the waterfront is a famous well called the Well of the Bishop of Adran (Puits de l’éveque-d’Adran), which gives the best water in all of Cochinchina and supplies Saigon and surrounding areas as far afield as Go-Cong.

An arroyo at Chợ Quán

On our way back to Saigon, we pass the village of Choquan, where a hospital was founded for indigenous people. This hospital also houses the dispensary. Contagious diseases, sores, scabies and skin lesions are very numerous among the population of Cochinchina and are more dangerous here than anywhere else. So this hospital is of great benefit to the Annamites.

We travel onwards between long rows of huts. The road is cut by several bridges, from where one can enjoy a very picturesque view of arroyo-Chinois, framed at the moment of high tide by scores of junks, boats and canoes manned by both Chinese and Annamites. During the rice harvest, in late January, one may see up to 400 sea junks moored in two parallel lines downstream of the arroyo, waiting to be loaded up with rice destined for the provinces of Upper Cochinchina.

We return to Saigon by the beautiful quai de l’arroyo-Chinois; this is the commercial quarter of the city, and it is also a most agreeable area to visit.

Charles Lemire

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.