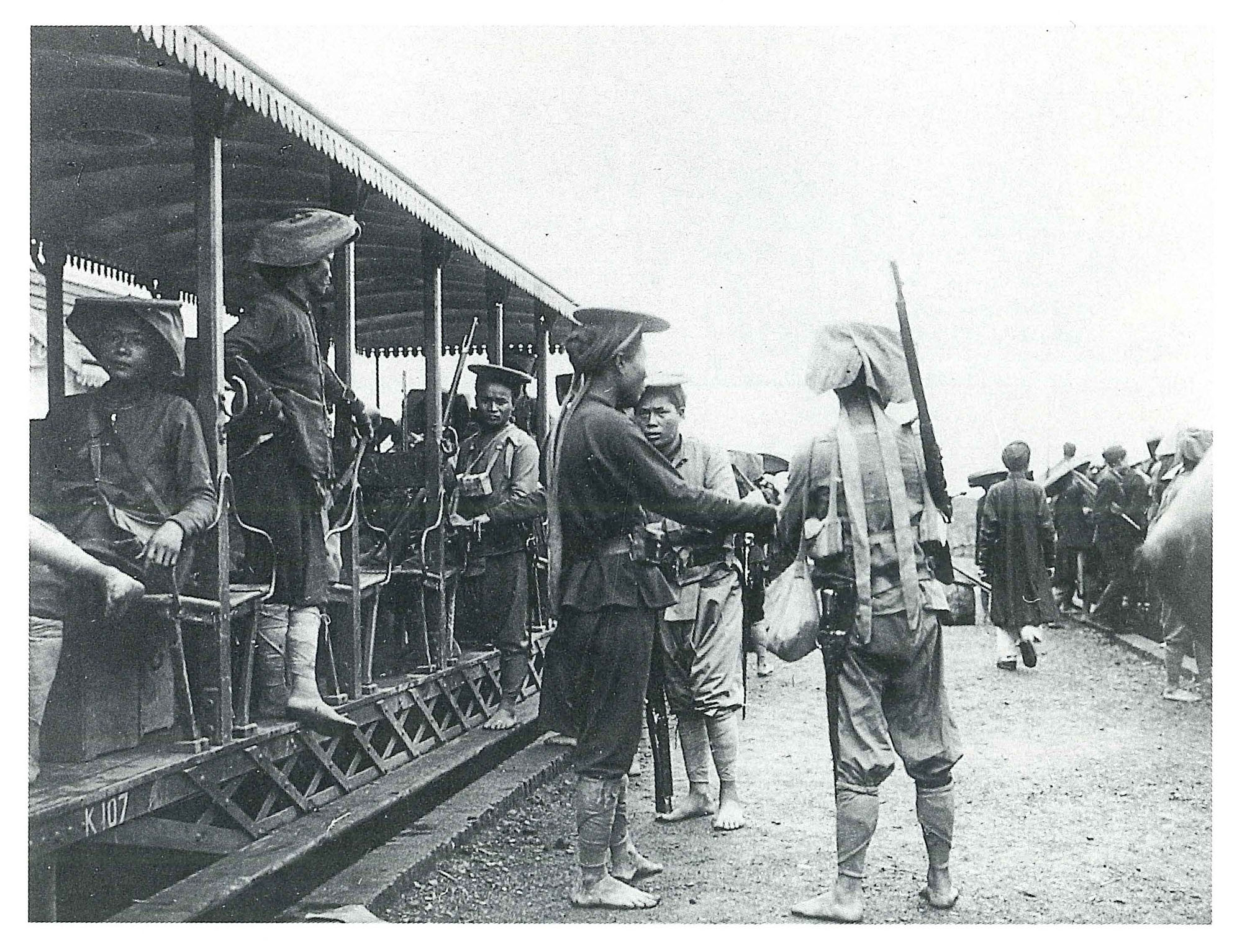

Tonkin, 1890s – Vue d’un train chargé de passagers, œuvre de François-Henri Schneider, showing a 0.6m gauge Decauville 0-4-4-0 (0220) “Mallet”

Translated from “L’Experience Tonkinoise: le Chemin de fer Phu Lang Thuong à Lang Son” by J P Vergez Larrouy, Chemins de fer regionaux et urbains, No 239, 1993-IV

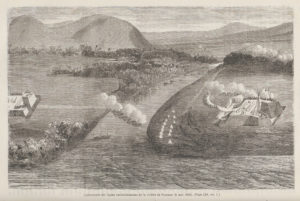

Tonkin became a French protectorate in 1884; in the same year, the first railway projects saw the light of day. It seems that the first appearance of rail in northern Indochina dates back to 22 August 1885, when a small horse-drawn tramway was inaugurated, linking the French concession in Hà Nội with the Citadel. The “pacification” then experienced some difficulties in Tonkin, more particularly on the side of the border of Guangxi where the Pavillons Noirs and the forces of Đề-Thám put Galliéni’s troops to the test. The mountainous topography of the country posed many problems for the evacuation of sick and wounded, and for the provisioning of certain garrison posts like Lạng Sơn or Cao Bằng. All these factors would lead the soldiers to lobby the authorities for the creation of a railway line to supply the border posts.

Résident Supérieur Paul Bert, thinking big, wanted to establish a vast network of railways in Tonkin. On 18 March 1887, a technical commission for the Tonkin railways was created; its composition was as follows: Edmond Fuchs, Chief Mining Engineer, representing the Ministry of Finance; Captain de Cuverville, representing the Minister of the Colonies; Lax, Chief Engineer of Roads and Bridges; the Director of Railways, representing the Public Works Department; Marie, the Director of Foreign Trade, representing the Minister of War; and Getteb, Engineer of Roads and Bridges, who acted as secretary

The Commission defined a network project, which was entered in the Official Journal of 29 August 1887 and envisaged the creation of three lines:

– Hà Nội to the sea

– Hà Nội to the Chinese border through the Red River Valley

– Bắc Ninh to Lạng Sơn

Having defined the network to be built, they hastened to forget it; Indochina was far away, and for metropolitan parliamentarians, it could prove to be dangerous; everyone remembered the fall of Minister Ferry, brought about by the famous “retreat” from Lạng Sơn. Disappointed by having to wait, the soldiers applied pressure; the line heading towards the Guangxi border was in their eyes most important: “The circumstances which motivate the creation of a Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn railway line are both political and economic; they have as their starting point the absolute obligation to provide military supplies to Lạng Sơn, which currently involves an annual expenditure of one million francs.” It seems that the prospect of making some savings won the decision of the Minister, who gave his support to the military. Teams immediately set off to reconnoitre the possible route, but these studies proved rather sketchy. Many people were interested in the line, and several applications for concessions were made. The affair seemed well started when – one does not really know why – the Minister of the Colonies suddenly decided that the line would be built with a track gauge of 0.60m, and that all the rolling stock and other equipment would be provided by the Maison Decauville. This decision was far from a unanimous one, especially among the colonials. The Minister nonetheless stuck by his decision, and work began in 1890. Given the restrictions in crossing the region by the general insecurity and by the carelessness of the successful tenderer, these works took much longer than expected. Inaugurated at the end of 1894, the line would give not very satisfactory results, and would quickly be transformed into a metric track.

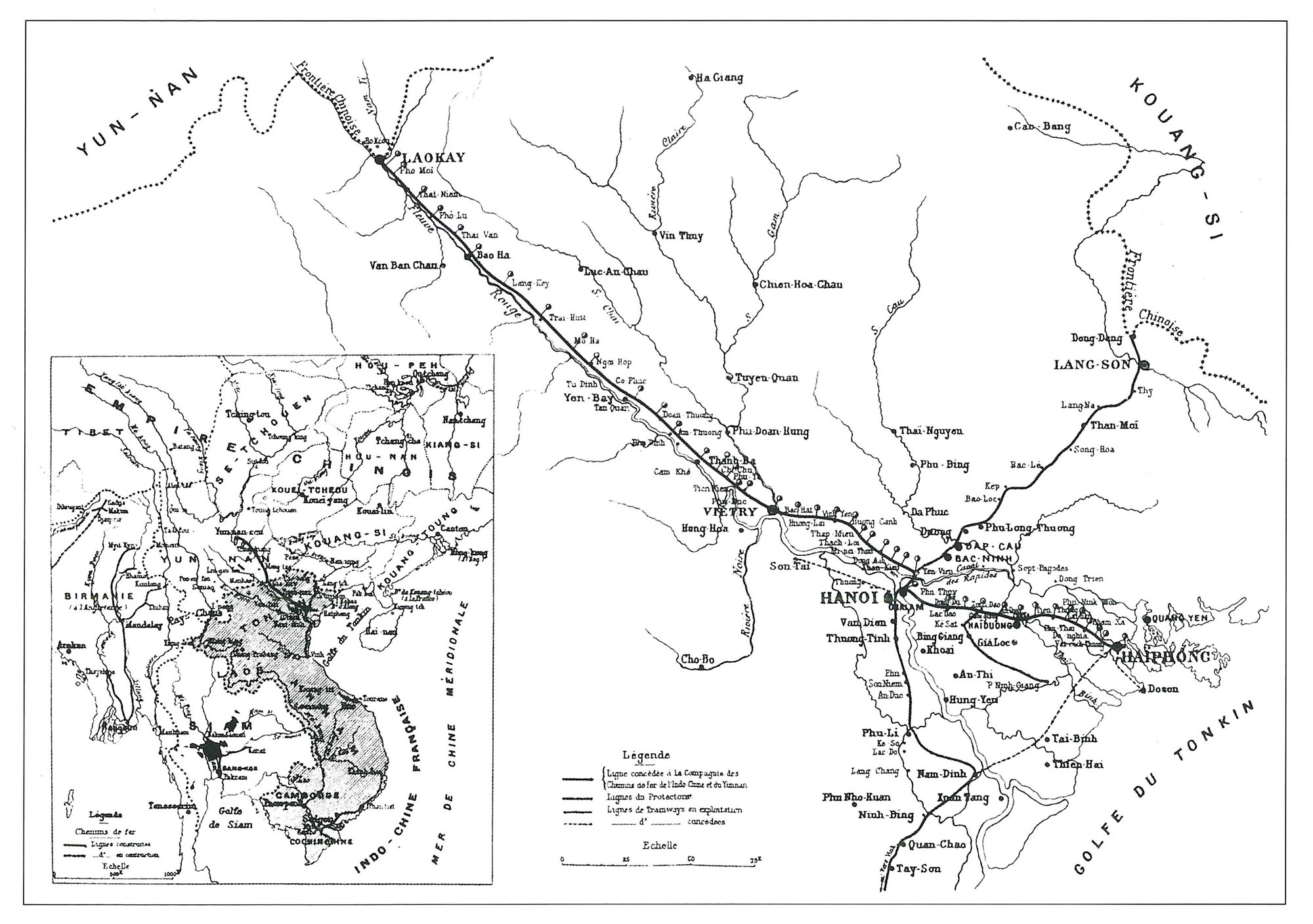

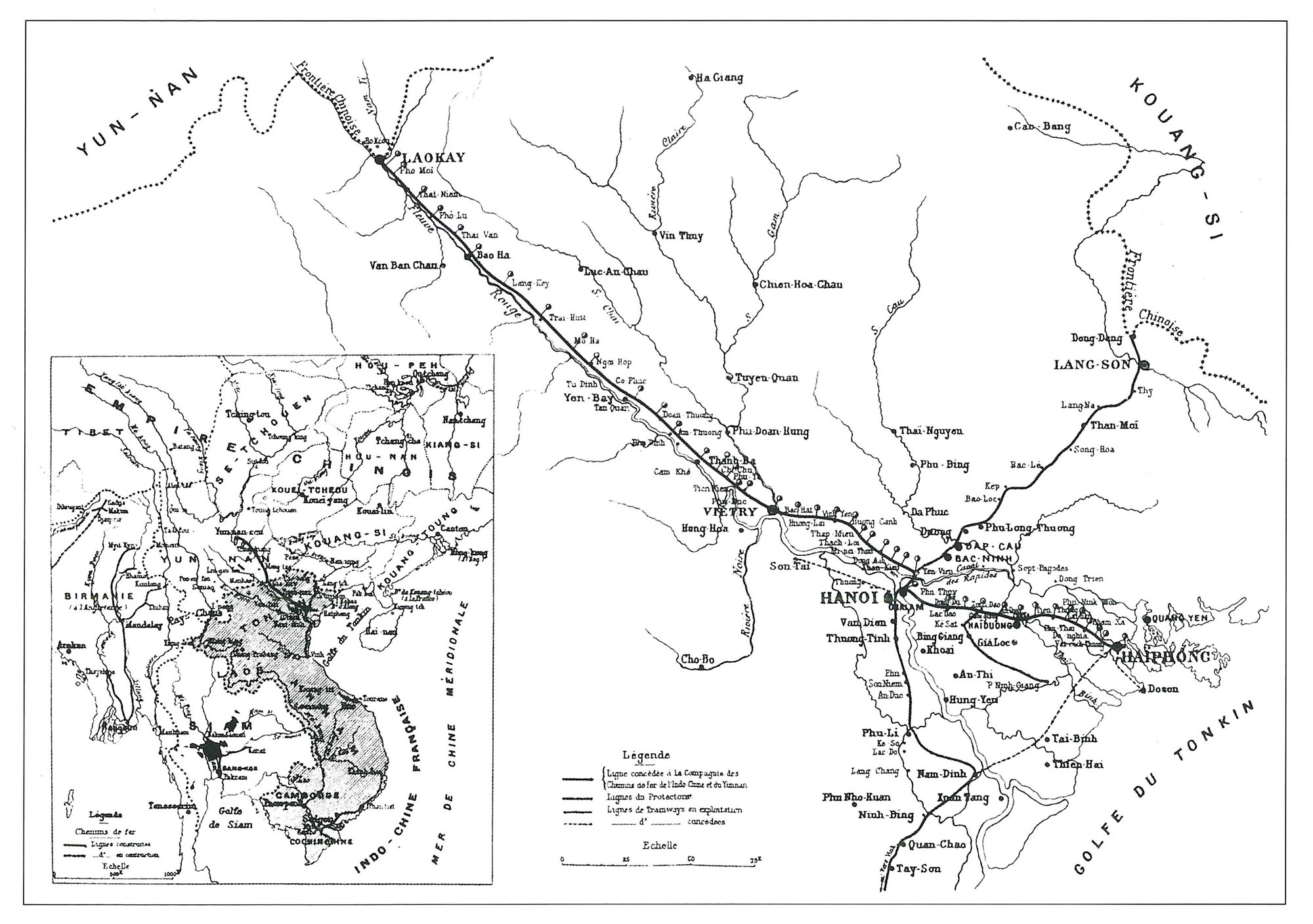

Route of the Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn line and the Hà Nội-Phủ Lạng Thương and Lạng Sơn-Đồng Đăng extensions, in the context of links with China; this route is therefore that of the line after its conversion to metric gauge from 1896 to 1902

1 The first concession requests and the study of the route

Various private companies were interested in the Lạng Sơn railway; applications for the concession of the line were filed in 1884, 1887 and 1888. The best studied project was that of Thomas, dated November 1887. Taking into the account the possibility of further extensions to Đồng Đăng, Thất Khê, Cao Bằng, and possibly Thái Nguyên, it provided for the construction of a road 4m wide, with the railway installed on it, at a distance of 30cm from the edge. The start of works was scheduled for 30 June 1888, and the project was to be completed by 31 March 1889. Engineer Fuchs was responsible for carrying out a synthesis of the various projects presented. At the same time, the Tonkin Public Works Department was requested to carry out a new study of the route, and it immediately set to work.

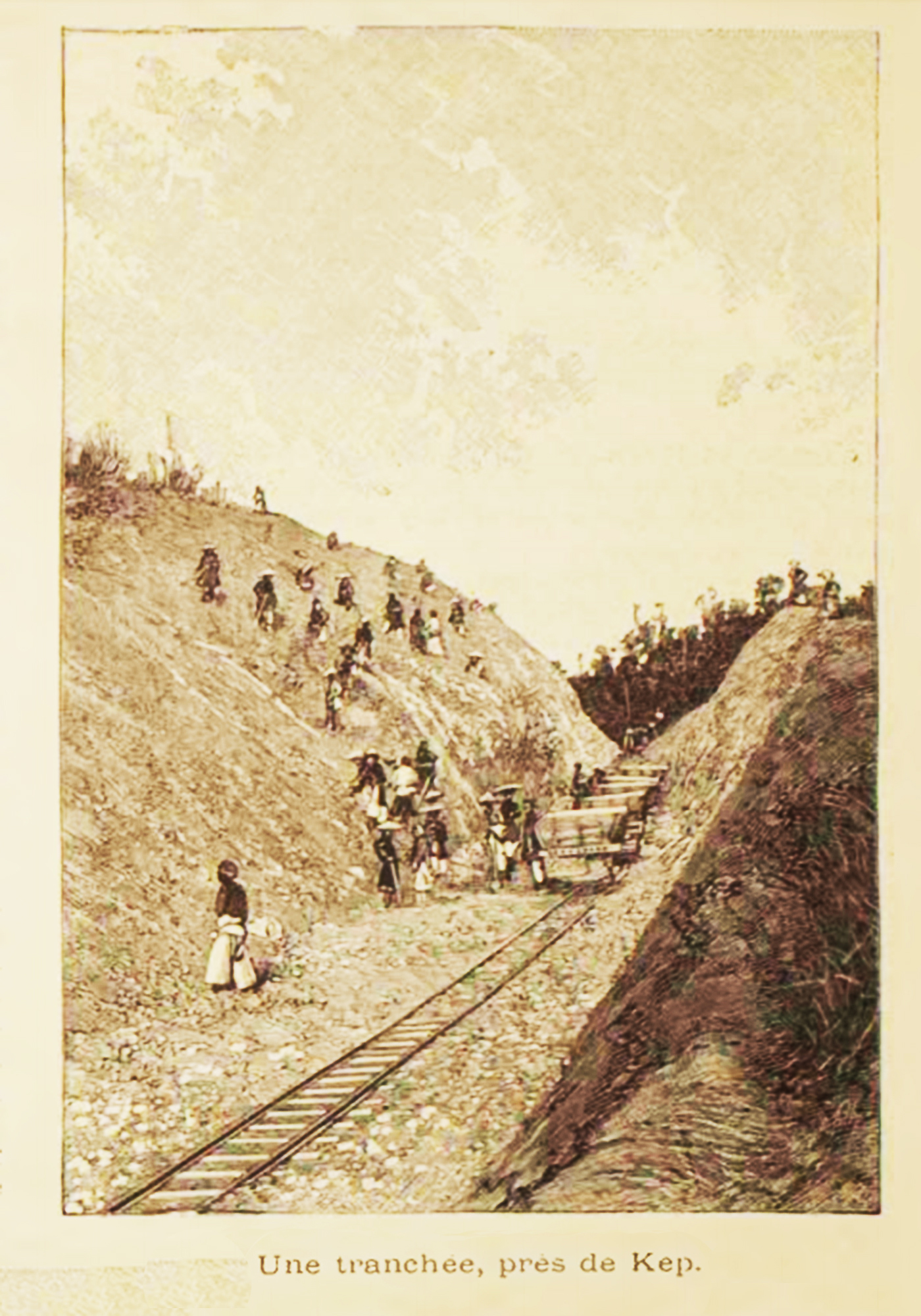

From Kép, several variants were retained, but the bad weather caused significant delays in the progress of the works. The most difficult problem, however, was finding labour; in his report to the Résident Général in Annam-Tonkin of 18 May 1888, the Consulting Engineer of the Protectorate admitted: “It is very difficult to find workers, despite the small task imposed on them and the high salary reserved for them. No worker in the delta wants to go beyond Phủ Lạng Thương and if, by known means, they are forced to go further, they take advantage of all circumstances to leave, even giving up their wages.” Out of 10 Chinese labourers sent by the Resident of Lạng Sơn on 24 April 1888, eight had already abandoned the site on the 30 April, after being paid. Despite everything, the work progressed. It was decided to build Lạng Sơn station at the entrance to the town, in order to defend it more easily against a possible Chinese invasion.

Once the study was completed, a report was submitted to Parreau, Résident Général in Annam-Tonkin. The latter transmitted the report to his superior, not without noting: “It will be easy for you, Governor General, to appreciate the usefulness of the future line from Phủ Lạng Thương to Lạng Sơn, from a political and as much as from an economic and commercial point of view. ” Governor General Richaud in turn sent the file to the office of the Minister of the Colonies on 19 October 1888. According to the terms of the report, the line from Phủ Lạng Thương to Lạng Sơn was no more than a simple section of a future Hà Nội-Lạng Sơn line, itself entering into the more general framework of a vast program known as “Tonkin’s railways;” it was planned to establish the line on the “Route Mandarine,” and the expenditure for the construction of the line was estimated at 8,561,066 francs. The author of the report proposed that the concession be awarded to a private company which would then build and operate the line.

The Indochina administration followed the advice of the Public Works Department, and started searching for a concessionaire. Negotiations were opened with the Marquis de Mores, who had declared himself interested; they were on the verge of coming to an agreement when everything changed: “At the moment when an agreement relating to the railway was going to be signed between the Governor General and the Marquis de Mores, an order arrived from the Minister to agree nothing without submitting the project for his approval. Consequently, the Marquis returned to France with his engineer and the studies were interrupted. Even if the affair did not drag too much in Paris, this caused a delay of at least a year (Saigon Republicain, 8 May 1889). Why this sudden turnaround? Would the railway be abandoned once again?

2 The Minister’s choice and colonial objections

2.1 A questionable choice

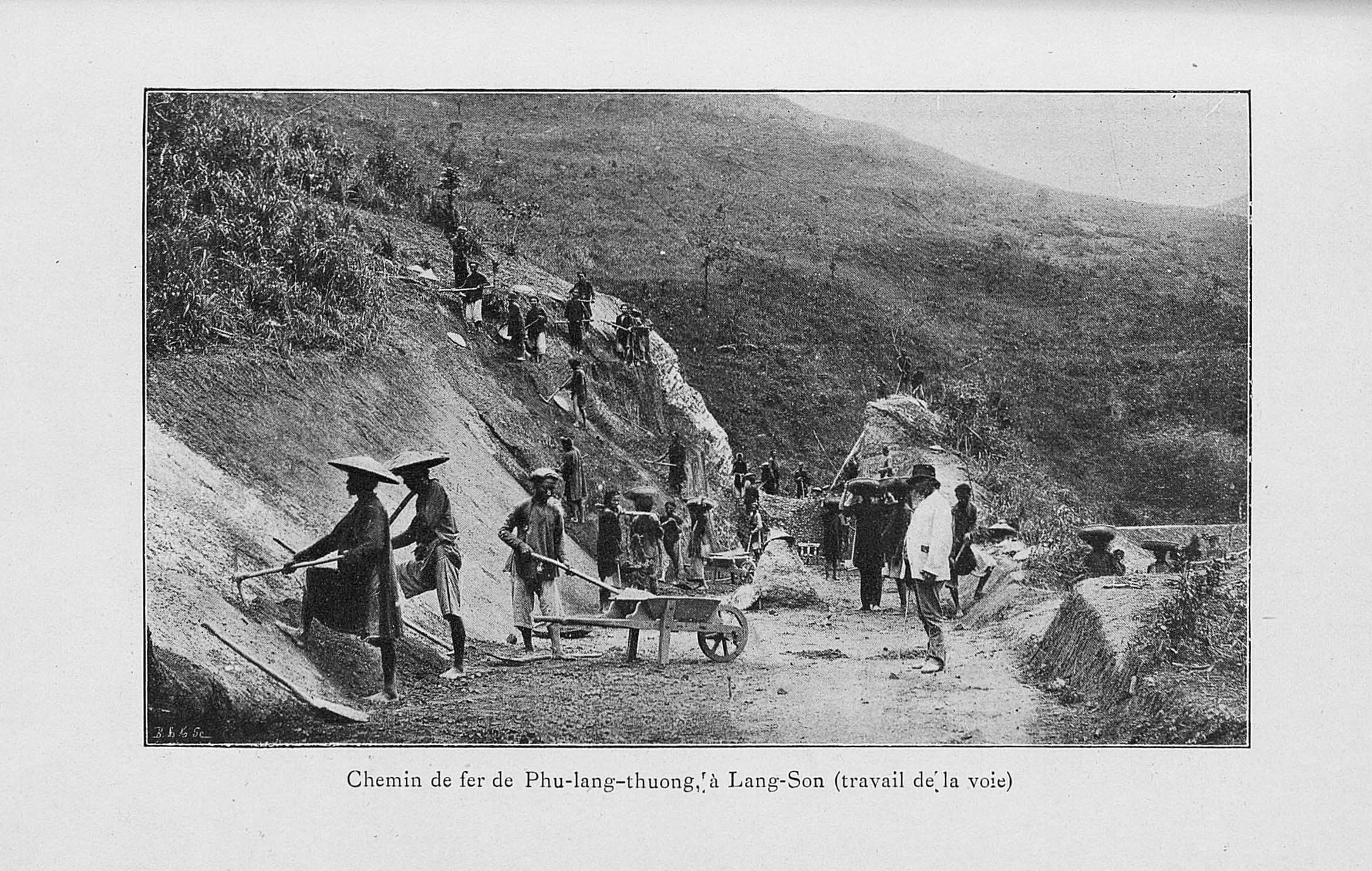

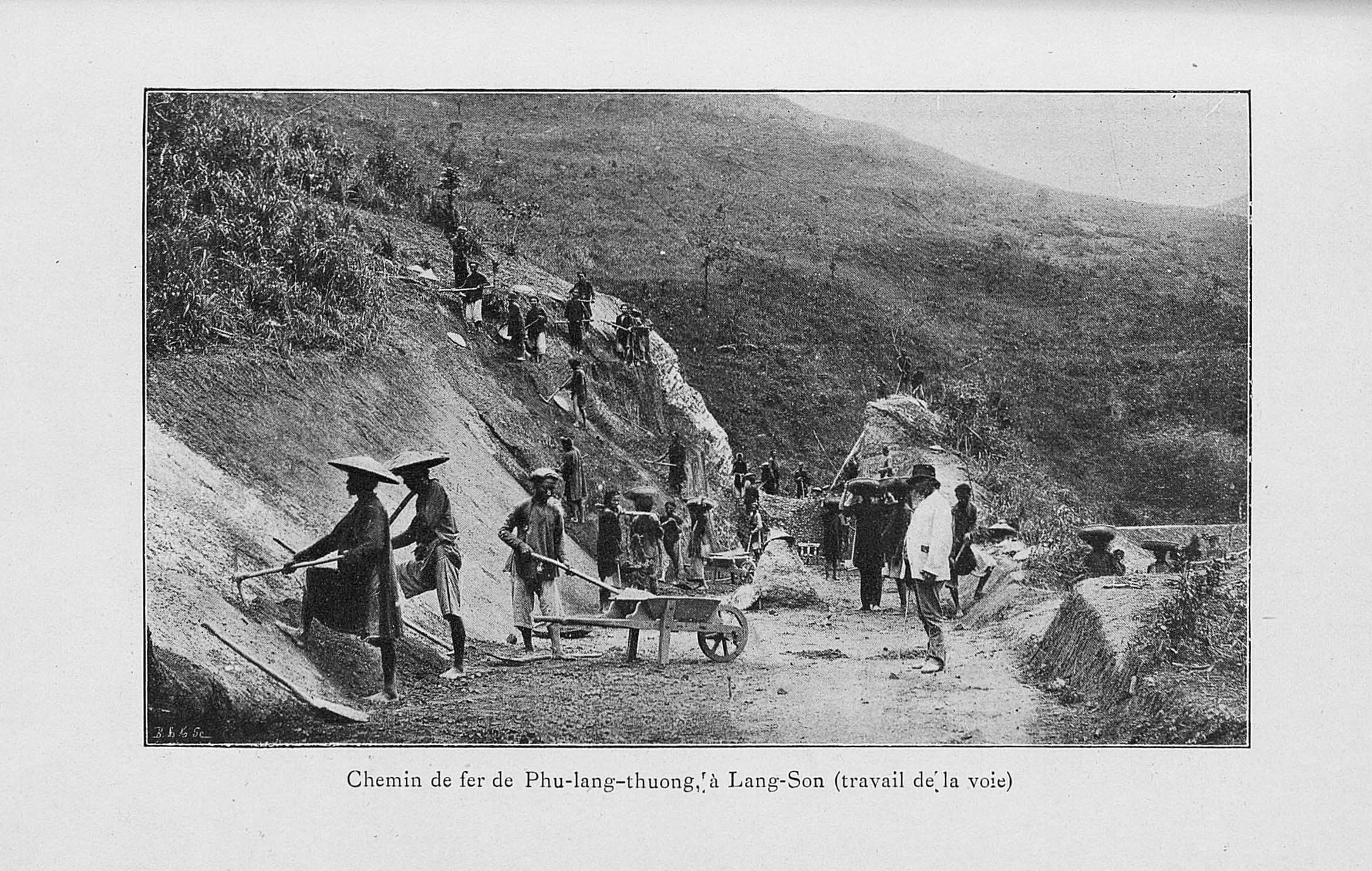

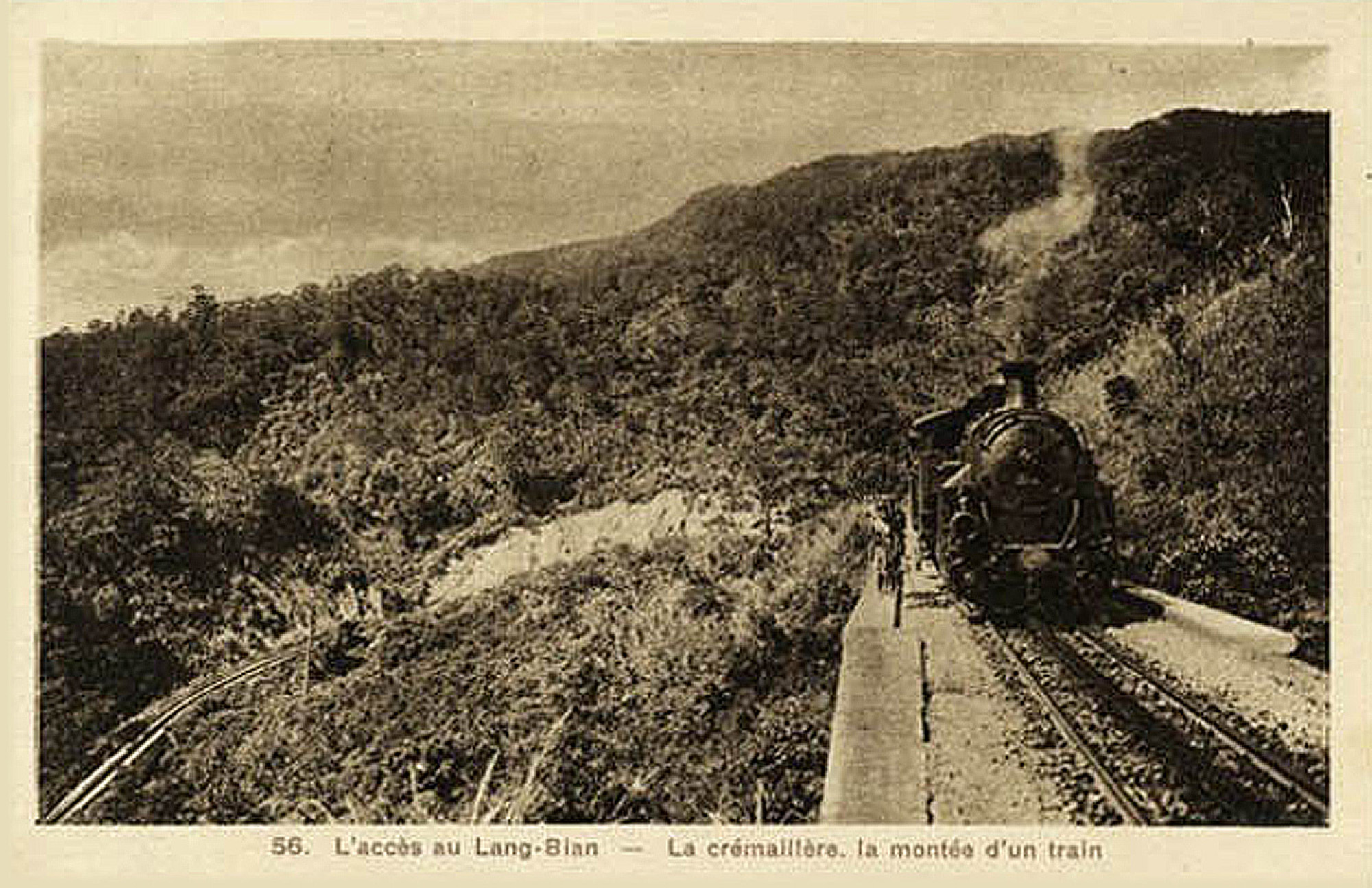

“Chemin de fer de Phu-Lang-Thuong à Lang-Son (travail de la voie),” Pierre Nicolas, Notices sur l’Indo-Chine, Cochinchine, Cambodge, Annam, Tonkin, Laos, Kouang-Tchéou-Ouan, 1900

Having more or less studied the file, the Minister of the Colonies asked the Governor General of Indochina whether the Public Works Department of Tonkin had the necessary means to establish a Decauville railway line along the Route Mandarine (Colonies to Governor General, Telegram No 728 of 11 April 1889). The least we can say is that the prospect of a Decauville line was given a rather chilly reception in Indochina. Having taken advice from his Director of Public Works, the Governor General sent this rather unfavourable response: “The road from Phủ Lạng Thương to Lạng Sơn does not actually exist. It’s little more than a simple track. The Director of Public Works considers that in these conditions, the establishment of a Decauville line for which the infrastructure would have to be fully executed would constitute the most expensive solution; it would be better to stick to a regular railway of 1m gauge, if sufficient resources are available.” In addition, the Indochina Public Works Department did not have any material available to build a railway. On 16 April 1889, the Minister of the Colonies telegraphed to the Governor General: “Have a firm proposal for Decauville. Would cost about two and a half million, rolling stock included. Decauville would be paid in two and a half years, and budget would not have to support the operation of the line valued at 150,000 francs per year. ”

It appears that the Governor General, complying with the Minister’s directives, gave orders for the establishment of a railway. However, all the answers he received were unfavourable. The Colony’s Director of Public Works, together with Engineer of Roads and Bridges Lion, pointed out that “a Decauville railway between Phủ Lạng Thương and Lạng Sơn, over a length of 108km, is too basic and too delicate a means of transport to abandon the idea of also constructing a good parallel road.” He added that “The expense will be much greater than it seems.” Full of common sense, he finally noted: “By proceeding to an adjudication, we could have 0.60 gauge track and rolling stock at least as good as that of Decauville, and under much more economical conditions.” The Commissaire general raised objections of a geological nature: “Land between Phủ Lạng Thương and Lạng Sơn consists of shale clay …. On such land, installing a Decauville line would be expensive, precarious, and would only be sufficient for transport with a parallel road… building such a Decauville line won’t be finished anytime soon.” (Telegram of 17 April 1889). In response to a request for studies from the Résident Supérieur, Engineer Lion rightly pointed out that there were no studies for this line, “except for that of the 1m gauge railway, made formerly under the direction of Monsieur Fauquier.” Even General Bichot, expressing the views of the military, said that he had not hesitated to telegraph the Governor General the fact that he had “little confidence in Decauville.” The credit of 400,000 francs intended for the preparation work also seemed to him “absolutely derisory,” he estimated the cost of the operation to be “at least 15 million francs.” However, the Minister of the Colonies persisted, developing a rather strange argument. He declared that he did not understand why, having requested a 1m gauge railway, the Governor General now rejected a Decauville line “which will be built in 10 months and will also give time to carry out complete studies on the railway network to be established in Tonkin.” The Minister argued that if the subsequent creation of a railway line from Hà Nội to Lạng Sơn was decided, the Decauville line could still be extended between Lạng Sơn and Cao Bằng; moreover, the Decauville line would make it possible to ensure permanently “the supply of Lạng Sơn and the comfortable transportation of the sick, food and troops” (Telegram of 22 April 1889).

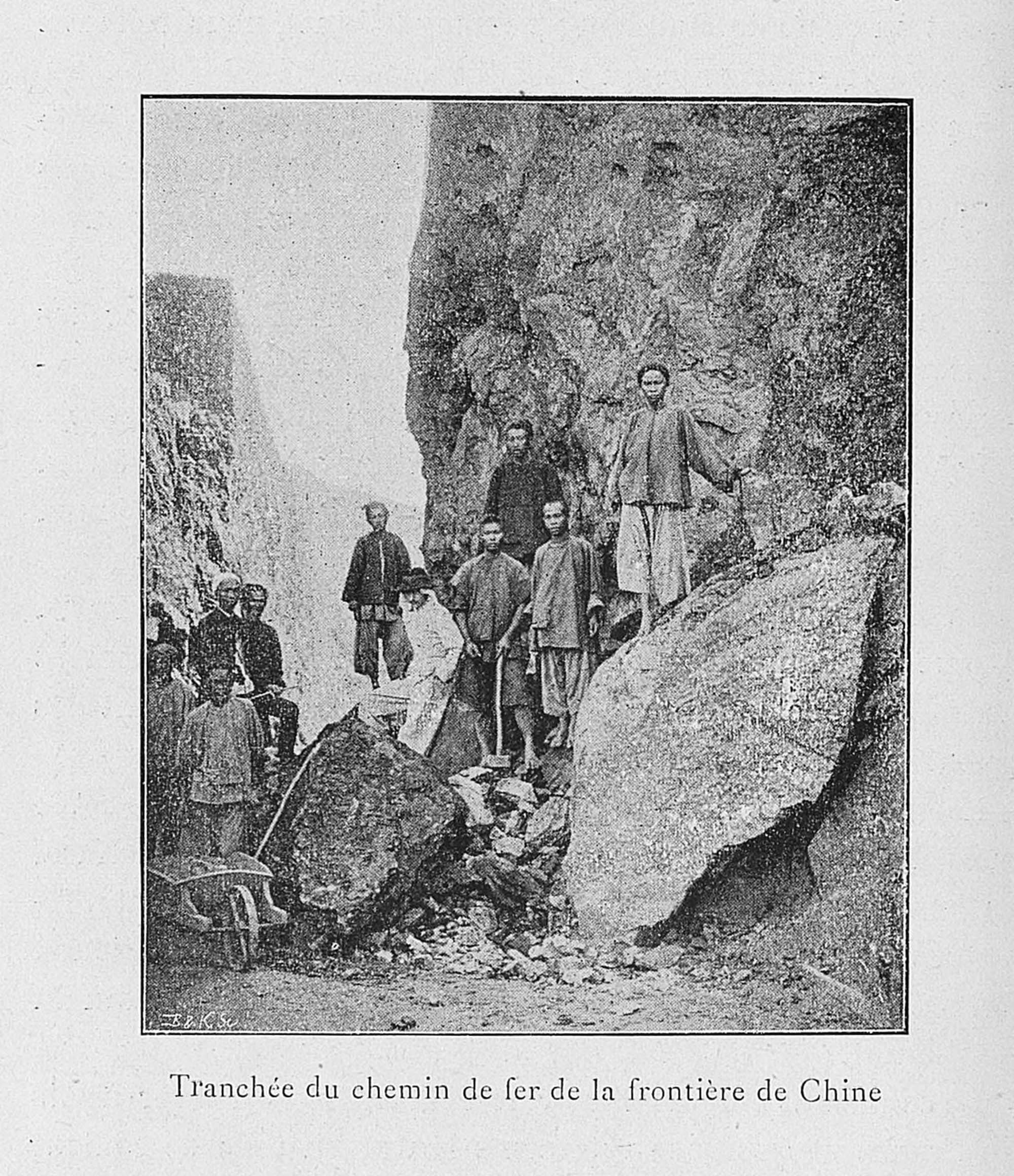

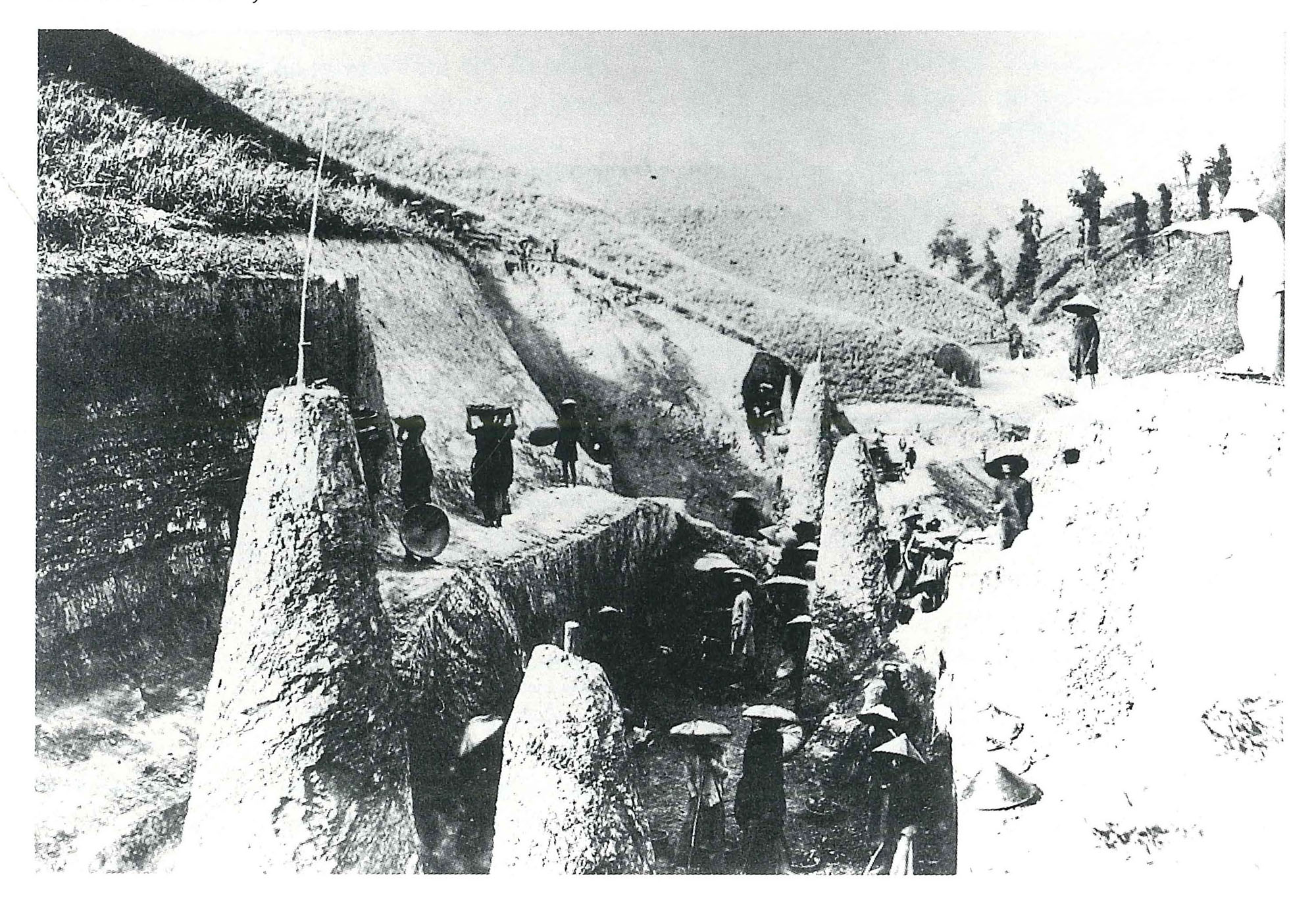

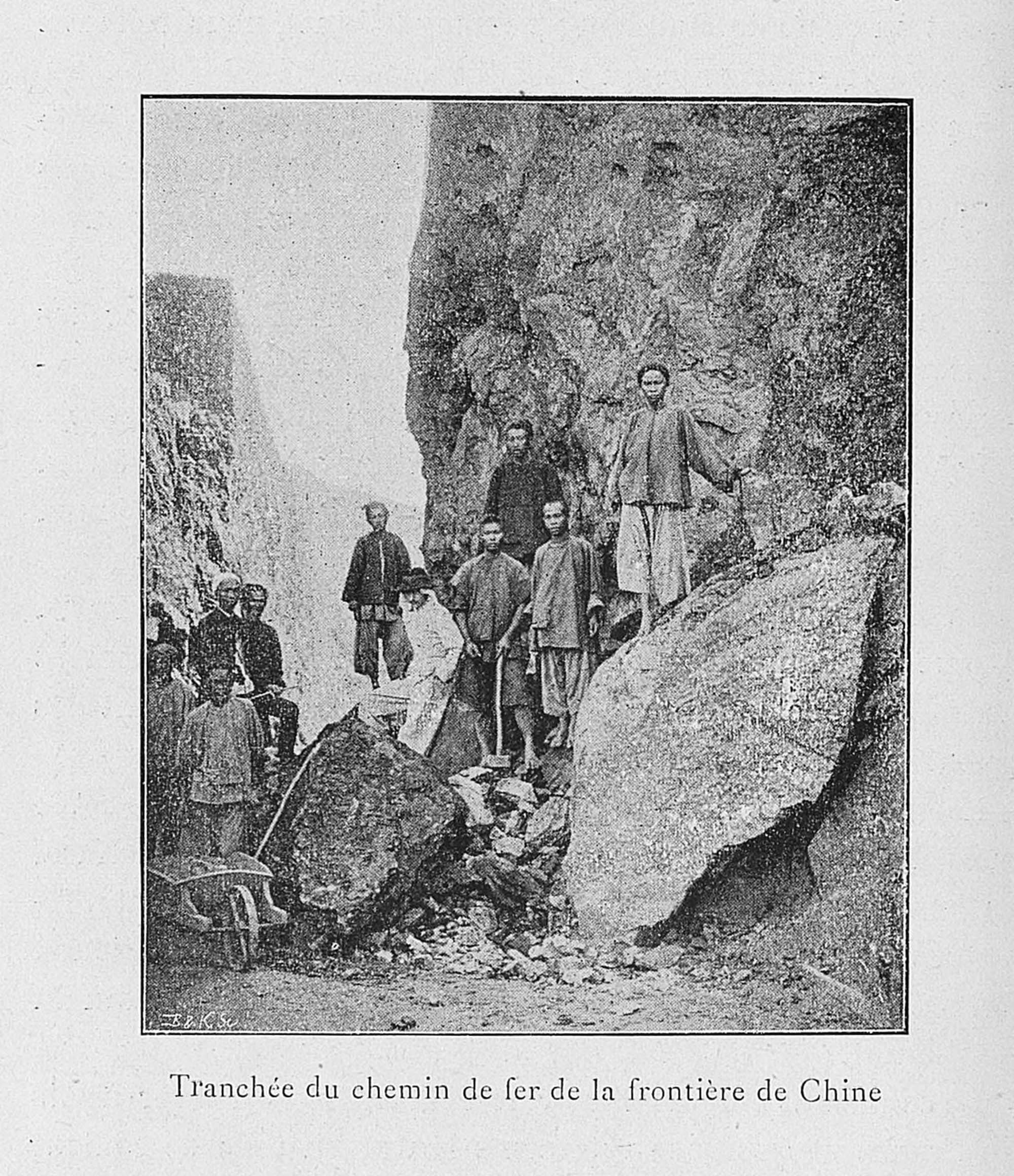

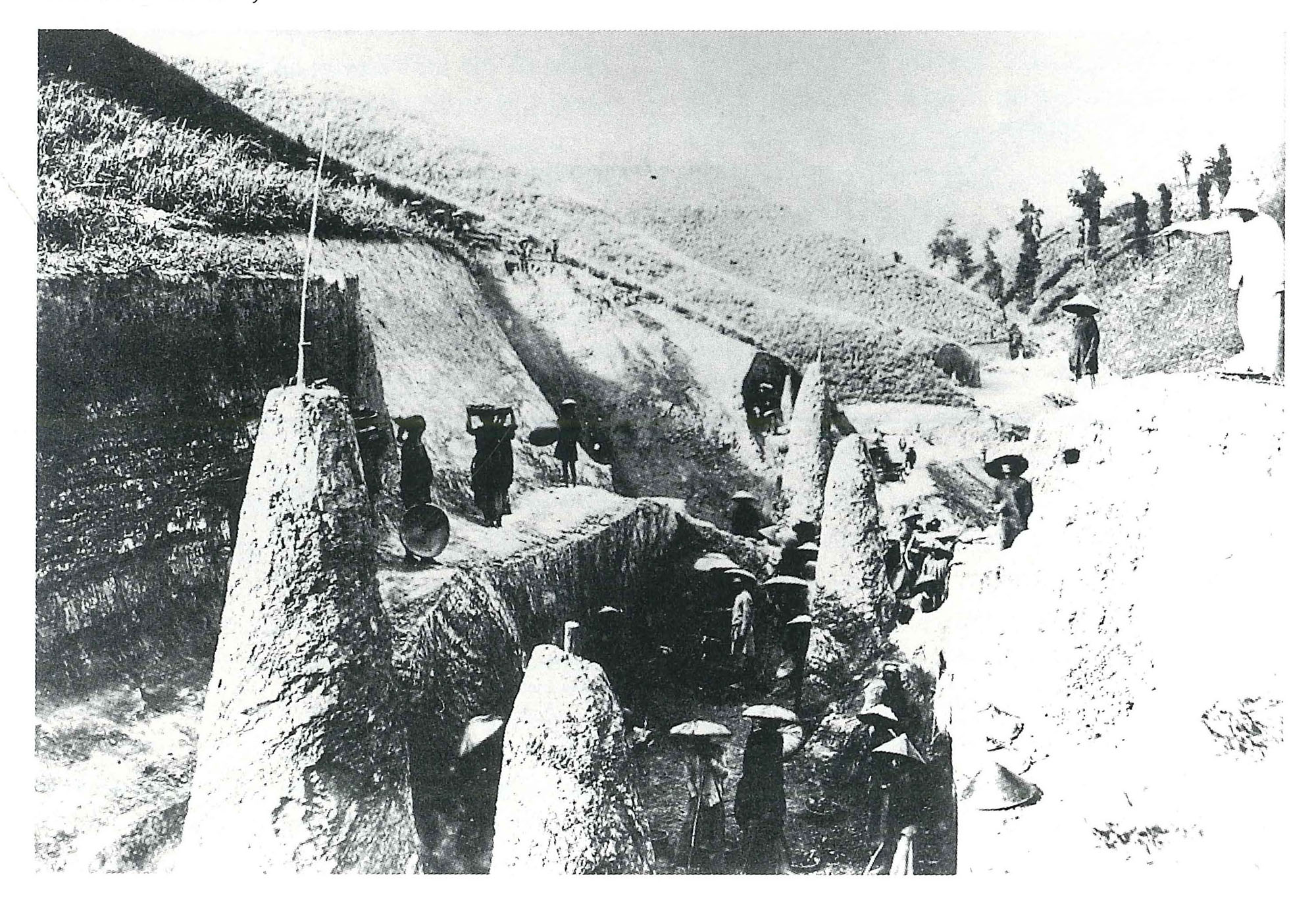

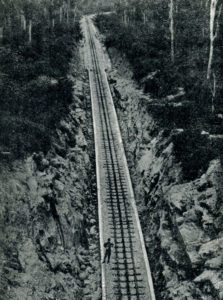

“Tranchée du chemin de fer de la frontiere de Chine” (Cutting on the railway at the Chinese frontier), from Pierre Nicolas, Notices sur l’Indo-Chine, Cochinchine, Cambodge, Annam, Tonkin, Laos, Kouang-Tchéou-Ouan, 1900

What a curious theory! Let’s go in the same direction as Engineer Lion and recognise that a railway of 1m gauge, even a simple road, would bring the same result! If it was planned later to build the line from Hà Nội to Lạng Sơn of 1m gauge, it is difficult to see what value the initial construction of a 0.6m line could bring! In addition, if the main line from Hà Nội would be of 1m gauge but the Lạng Sơn-Cao Bằng line remained a Decauville line, the only result would be to create a break-of-gauge problem in Lạng Sơn, hence a loss of time and an unnecessary increase in operating costs. Let us note in passing that, once the Hà Nội-Lạng Sơn line had been transformed into a 1m gauge track, the Decauville would never be built between Lạng Sơn and Cao Bằng, leaving in place only the famous RC4.

2 Why did the Minister impose the Decauville system?

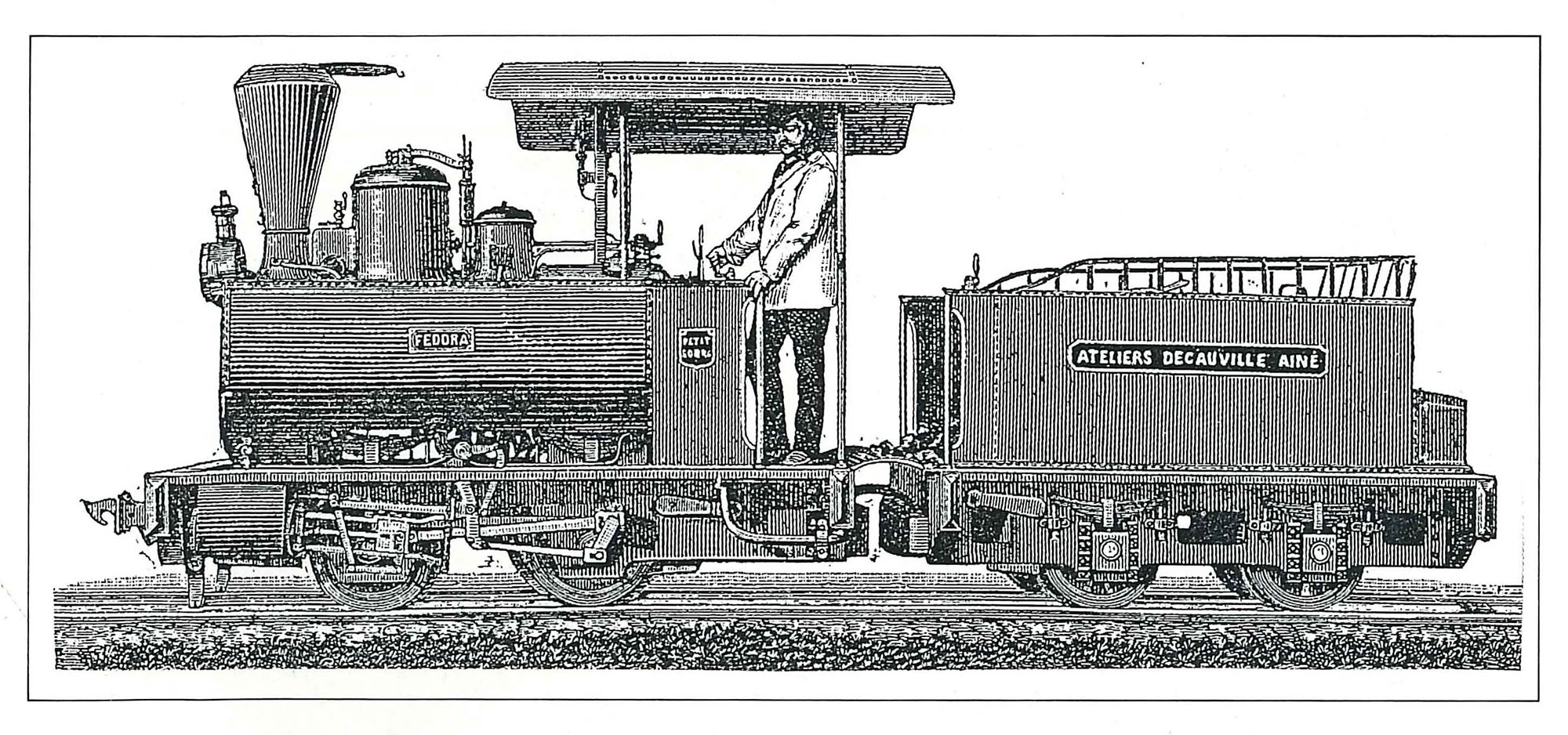

How to explain the stubbornness of the Minister of the Colonies in this affair? The 0.6m line was developed after the defeat of 1870, and the military were the main users; Colonel Prosper Péchot (1849-1928) had made himself the champion of the system, which was beginning to be used widely in mines or plantations overseas. The publicity of the Corbeil firm focused on its economy and on the lightweight features of the track. But that lightness of track had brought some setbacks for Decauville; a first experiment had been attempted in 1882 in Tunisia, between Sousse and Kairaouan. Very quickly, it was noticed that “the sleepers, riveted but leveled to the right of the running edge of the rail, left the track insufficiently anchored, with a tendency to move with the passage of heavy loads.” The operation of this line quickly turned out to be disastrous, and faced with the impossibility of running locomotives there, they had to be satisfied with horse-drawn traction. So, an initial “colonial” experiment had been attempted using Decauville material, and it had been a failure. The Sousse-Kairouan line would be taken over by the Bône-Guelma in 1887 and reopened to the public, after transformation of the track, on 1 January 1889.

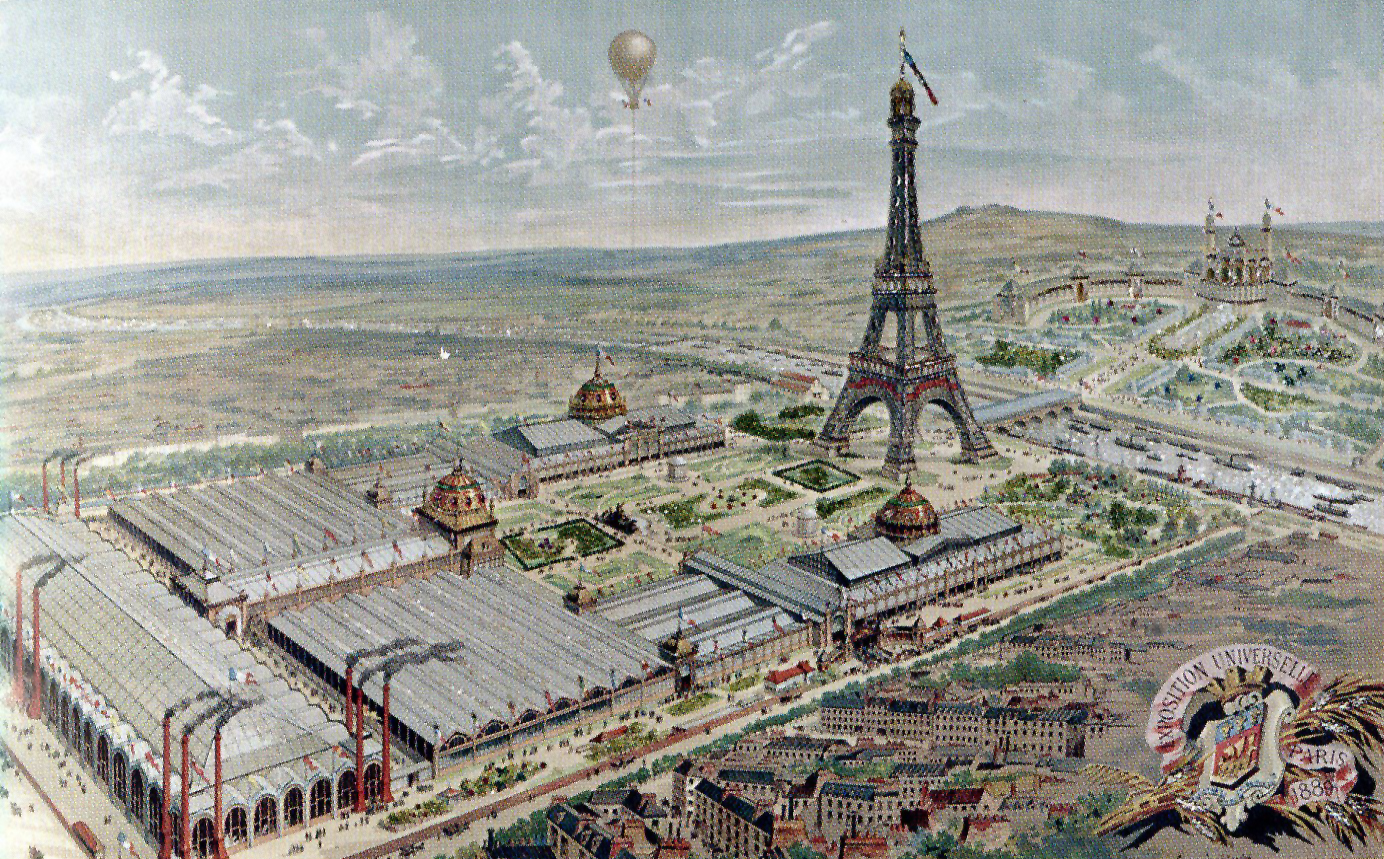

In Tonkin, we can say that the Minister “imposed” the Decauville system; to explain this choice, we are reduced to simple assumptions. Certainly, one can consider that Decauville had secured a “big advertising coup” by supplying the service railway at the Universal Exhibition of Paris in 1889. It is precisely in this connection that we discover the first surprising fact: The Minister gave the order to begin the works of infrastructure in Indochina on 24 April 1889. On this date, there was not yet any question of purchasing material, nor even of awarding a concession. However, when the Universal Exhibition in Paris was inaugurated by Sadi Carnot on 5 May 1889, the locomotives running on the exhibition railway were all “named after the main installations of the Decauville railway,” and significantly the Exhibition’s guestbook recalls that “one of these machines was named Hanoi,” a name which “relates to the small railways of Tonkin.”

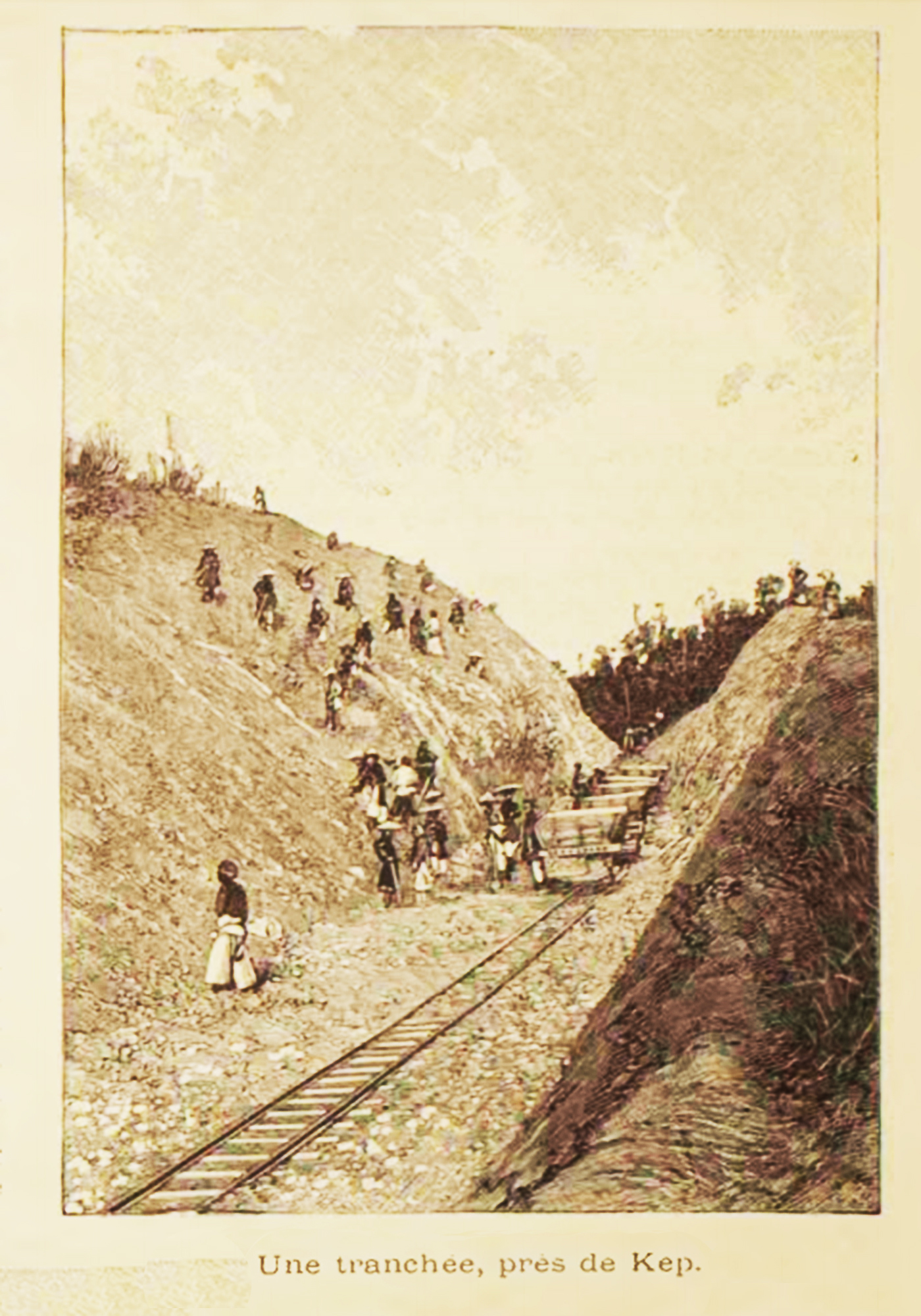

“Une tranchée près de Kép,” Le premier chemin de fer du Tonkin, l’Illustration, 4-2-1893, Vol 101, No 2606

However, if we exclude the mythical tramway in the Hà Nội Citadel, there was at that time no railway in Tonkin. The works of the Lạng Sơn railway would not be awarded until September 1889, more than five months after the start of the Exhibition; Decauville was of course on the Minister’s side!

For his part, the Minister of the Colonies was careful to point out that “the proposed railway is not the one used in Tonkin with the Péchot metal sleepers.” The omnipresence of the “sirens” of Decauville around the Minister seems undeniable; Coincidentally, all third-party companies brought in to bid for the Lạng Sơn railway supply would be those highly recommended by Decauville. For example, the Baillehache company, which would attempt, in 1892, to secure the adoption of its “electrical warnings and protection signals for railway tracks.”

One can also think that the “metropolitan military lobby” also played some role in the choice of the Minister, since the military recommended for Indochina a railway of easy construction and simple operation. In his telegram of 24 April, the Minister of the Colonies admitted having made his decision after favourable consultation with Generals Mensier and Begin, who had affirmed to him “the usefulness of the Decauville system.” When Lion received the order to begin work (letter of 26 April 1889), he immediately asked for information on the width and type of track adopted, the limit of the ramps and the radius of the curves, the weight of the machines and their number of axles, and – not without humour – whether the line was intended for mechanical or horse-drawn traction. Having enquired with the Minister of the Colonies, the Governor General gave the following figures: Width of the track 0.6m, minimum curve radius 20.15m, maximum declivities 35mm/m, locomotives of 9 tonnes able to haul 36 tonnes. With the exception of the information about the locomotives, we may find these very same figures in the Decree of Minister of War Freycinet, dated 4 July 1888. But that Decree concerned the use of 0.6m Decauville tramways inside military fortifications, certainly not the construction of a 108km railway line in Tonkin! In addition, the metropolitan military elite was fairly divided as to the characteristics of strategic networks; the engineers recommended the use of 1m gauge, while the artillerymen swore only by 0.6m gauge. However, the supporters of the 0.6m track were further subdivided into supporters of the Péchot system and supporters of the Decauville system.

Throughout this entire affair, it seems that the Minister of the Colonies permitted himself to be deceived by the supporters of Decauville; but the good deal they had dangled quickly turned into a financial pit. In December 1890, the Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies declared before the Chamber of Deputies: “I confess, gentlemen, I started work on the railway from Phủ Lạng Thương to Lạng Sơn without having at my disposal the sums which would be necessary to ensure payment.” The role of the metropolitan military is not very clear. Did they want to use Tonkin as a vast testing ground for their “strategic networks?” What must be remembered above all is that the Minister for the Colonies not only acted rashly, but also displayed total incompetence in matters of transportation.

3 Award of the contract and commencement of work

On 24 April 1889, the Minister gave the green light for the construction of the line; he remained convinced that a “serious and rapid study” would show that “the cost of the infrastructure will not exceed 400,000 francs.” In addition to the savings planned on infrastructure, the Minister also ordered that the expenses “of supplying lost or damaged food, and of the mortality of coolies and oxen (curious assimilation!)” should not be taken into account. On 26 April, the Résident Supérieur announced to the Gouvernment General that “studies will begin immediately,” and that the teams would leave the following week. The Minister remained resolutely optimistic, claiming that if the infrastructure dossier reached him before July, the Decauville line could be installed by March 1890.

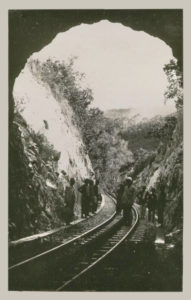

Earthworks for construction of a cutting, somewhere near Lạng Sơn. Collection C Daney

At the end of the fairly brief study work, specifications were drawn up; it was planned to entrust the construction of the line to a contractor, under the supervision of the local administration.

The successful tenderer had to pay for the material intended for the line, the administration reserving the choice of said material, the discussion of its purchase price, and the supervision of its construction. The successful tenderer was also responsible for transporting the material to Indochina, under its full responsibility; the payment of transport costs was to take place after delivery of the equipment to Phủ Lạng Thương.

The work of establishing the track bed would be determined and supervised by the engineer of the Protectorate, and carried out by the contractor as an “interested party,” who would also be responsible for supplying the necessary manpower.

The laying of the track was to be carried out by a contractor, under the supervision of the Indochina Public Works Department, and the tracklaying work had to advance by least 1km per day. Basically, the future contractor was therefore required to advance the sums necessary for the construction of the railway; the Minister provided for rapid reimbursement, the remainder to be settled in 1896.

The adjudication took place on 13 September 1889, and the winner was a Parisian named Georges Soupe. He immediately created the “Entreprise des Chemins de fer du Tonkin, Ligne de Phủ Lạng Thương à Lạng Sơn.” On 7 November 1889, Soupe requested and obtained an additional clause to the Convention of 13 September: not having the necessary funds to pay the advances he had undertaken to make, he asked the administration to provide him with facilities for finding credit. During the adjudication, therefore, certificates of guarantee were issued, which opened the door to the large banks. The financial situation of the operation thus becoming rather confused, a special account for the railway was created by the Under-Secretariat of State for the Colonies.

Purchases of fixed equipment and rolling stock began from 7 September 1889, the total cost being 2,296,924.50 francs.

All the heavy equipment, from rails to locomotives, was supplied by Établissements Decauville de Courbeil. Hoping to make some savings, the Minister of the Colonies had asked Decauville to provide him with second-hand equipment from the Universal Exhibition. But the company, which had already “hooked” the Minister, had no intention of making concessions; on 7 November 1889, Decauville replied: “We cannot make any discounts on locomotives or on rolling stock emanating from the Exhibition.”

In fact, Decauville delivery was rather piecemeal; a first order for six locomotives soon proved insufficient, and on 18 May 1891, a new contract was made for the delivery of additional equipment, that’s to say two more locomotives and 134 wagons.

On 2 March and 21 April 1890, ships of Messageries Maritimes arrived in Indochina, carrying the first crates of material. Three other ships, chartered by Georges Soupe, would leave in 1890: the “Mount Hebron” on 30 May, the “Dieppois” on 2 August, and the “Craigle” on 21 October. The first material unloaded in Indochina, on 2 March 1890, was a colonial house intended for the personnel in charge of the construction. In fact, all of the railway buildings seem to have been pre-manufactured in France: “A foreman arriving from France says that the buildings have been ordered in Paris and that he saw the Phủ Lạng Thương station completed.” (Letter of 24 February 1891). This led to some disagreements with Tonkinese officials, who were counting on showing off their abilities as builders.

The work really began on 2 March 1890, with great animation; Governor General Piquet telegraphed the Under-Secretary of State for Colonies: “I went to Phủ Lạng Thương this week. I visited the construction sites staffed with Annamite labourers, all working actively and in a much more satisfactory manner than we could have hoped for. Many such construction sites will be set up, in order to finish the earthworks of Phủ Lạng Thương station and the Phủ Lạng Thương-Kép section of the line before the hot season.”

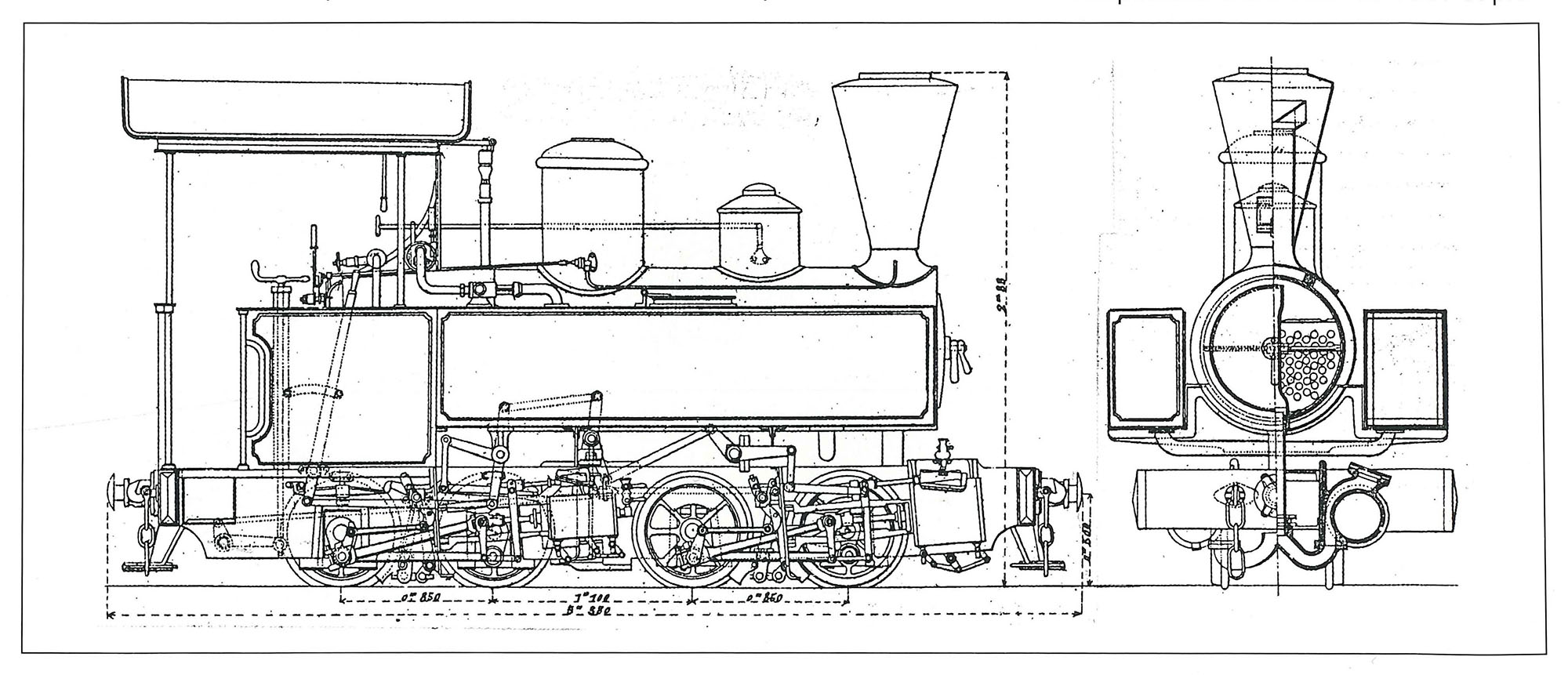

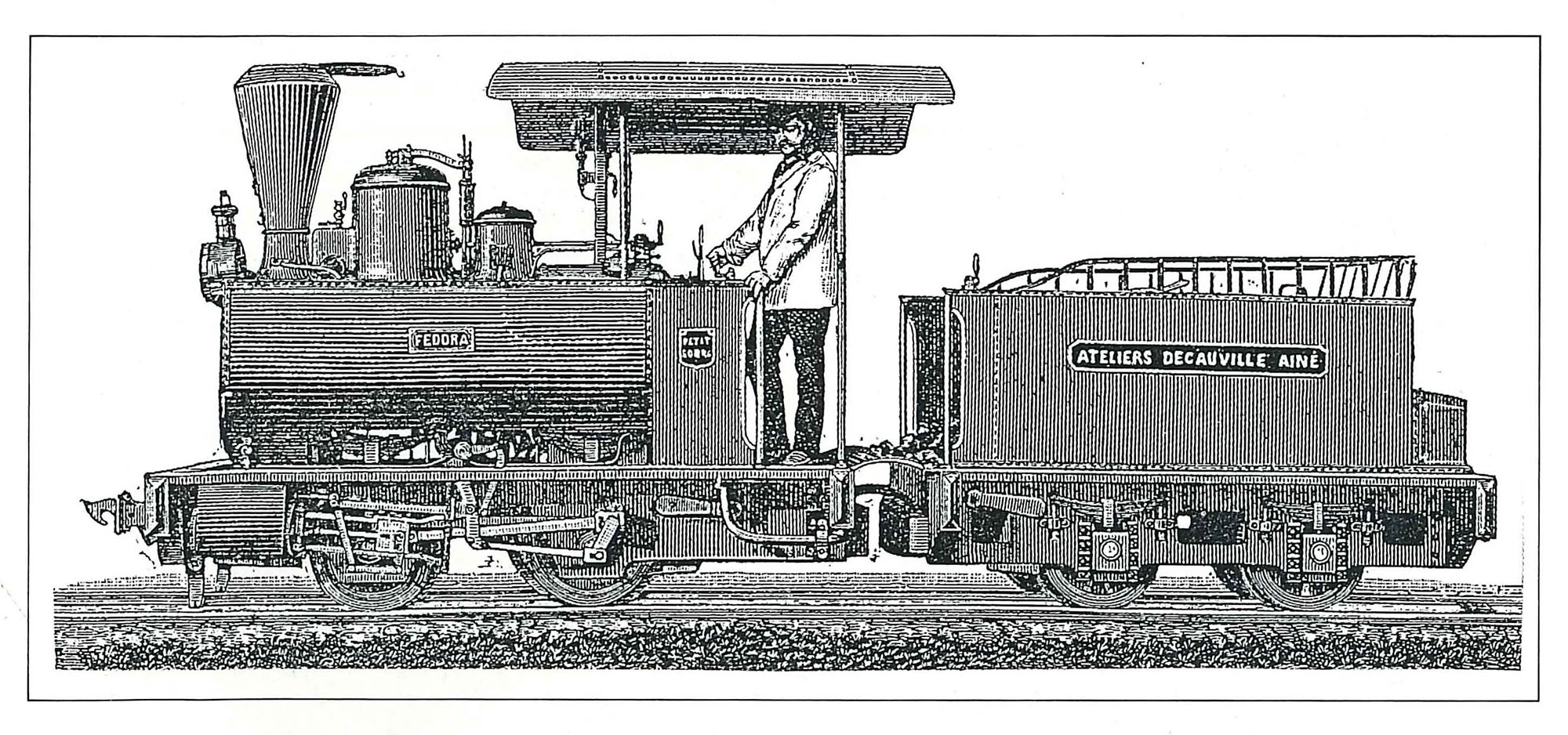

A 0.6m gauge Decauville 0-4-4-0 “Mallet” compound jointed locomotive on display at the Paris Exhibition of 1889

During the Summer of 1890, the sites were prepared and the necessary materials were brought in to work. In September, work began in four different locations, with “many construction sites,” and the first bridges were installed. But the sums involved were already over budget; the concessionaire took the opportunity to try to obtain a revision of the initial agreement, claiming that the contract of 13 September 1889 constituted a simple “opening of credit,” and that he was not obliged to continue his advances beyond the 3,876,106 francs provided for in the specifications; he therefore requested a modification of the latter. However, Fournié, Inspector General of Public Works of Indochina, found most of Soupe’s proposals unacceptable. After difficult negotiations, a compromise was finally reached on 3 November 1890. Soupe obtained an increase in the surcharges due, and some concessions on various technical issues (maintenance and ownership of construction equipment, etc).

As we have seen above, these different financial ups and downs would lead the Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies to make amends before the Chamber of Deputies; the main consequence was the vote by the Parliament of Article 45 of the Finance Law of 26 December 1890, which stipulated that “the projects relating to the construction and the execution of railways in Indochina will be provided to the two Chambers and adopted by them. “The Parliament agreed, all the same, to put a sum of 13,100,000 francs at the disposal of the Protectorate of Annam-Tonkin, “to liquidate all the deficits of the previous years.”

At the beginning of 1891, the remaining material on order arrived in Indochina, transported aboard the “Kimloch” (31 January 1891), an unidentified Messageries Maritimes ship (10 February 1891), and the “Teyiet” (20 September 1891). Meanwhile, work on the track bed was actively continuing, and would soon allow part of the line to be put into service.

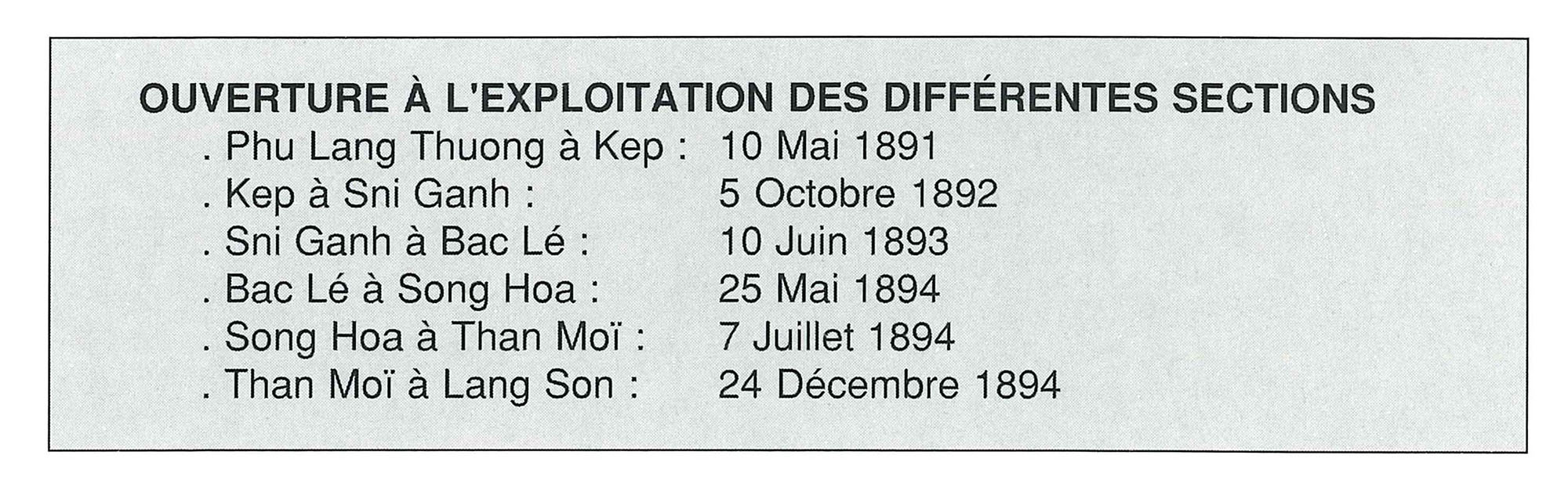

4 Inauguration of the first section, the starting point of controversies with the successful bidder

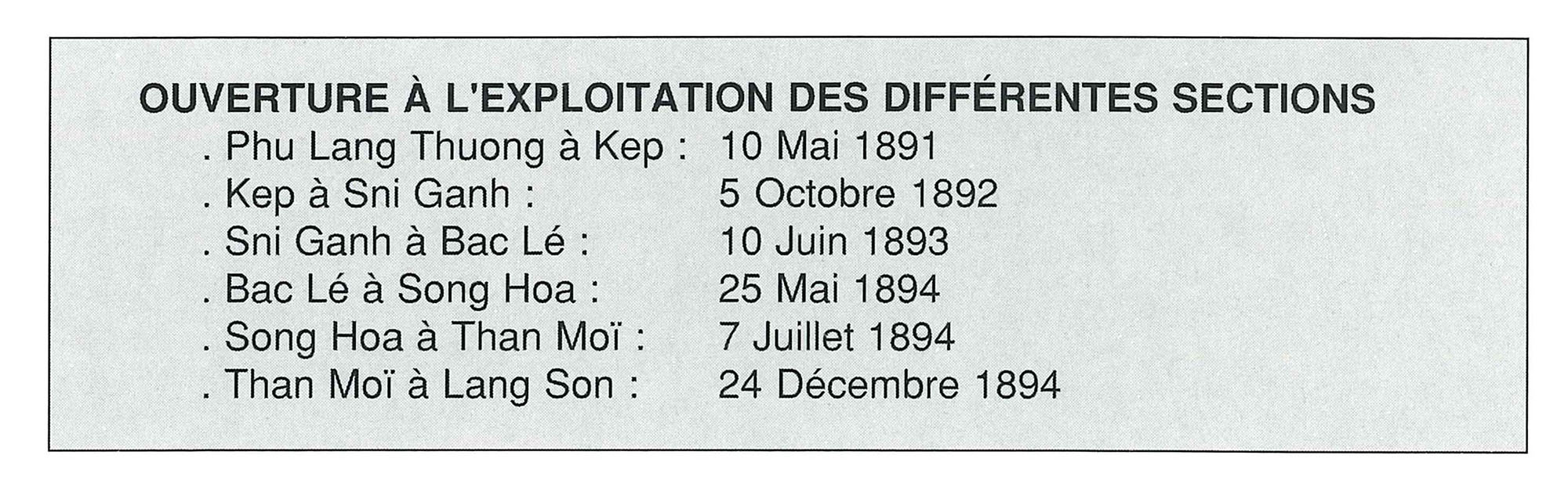

On 10 May 1891, a first 10km section of line from Phủ Lạng Thương to Kép was opened to traffic; the trip lasted 45 minutes. The inauguration took the form of a small ceremony, which took place without notable incidents; residents of Lạng Sơn and Hải Dương attended, as well as provincial mandarins, “in the midst of a fairly large crowd of the population.” As for military representatives, they avoided the ceremony, even those from Phủ Lạng Thương. “This abstention, which on such an occasion I cannot explain to myself, was the only detrimental aspect of the day.” (Résident Supérieur to Governor General, Telegram No 621 of 10 May 1891). The Résident Supérieur, assessing the rapid progress of the works, envisaged the opening of the Kép-Bắc Lệ section by the month of October. But he was very optimistic!

The attitude of the soldiers to the ceremony of 10 May was indicative of a prevailing malaise in relation to the railway; on 12 May, the engineer supervising the construction and operation services, Vesine-Larue, resigned following disagreements with the Director of Public Works regarding the construction of the line. It must be said that the Department of Public Works of Tonkin held the successful tenderer and his agents in very low esteem: “The company never organised its sites in a normal and economical way; moreover, until recently it never had the technical representatives who usually work on railways or other such installations. Its representatives were administrators who, in the silence of their offices, thoroughly studied all the clauses of the specifications in order to draw conclusions for their own benefit, while the construction sites were handed over to the direct charge of the cais (corporals) who controlled the workers. To these clauses, we must also mention the notorious incapacity of the site managers, who were recruited without care, most of them being lazy and having never worked” (Report of the Director of Public Works).

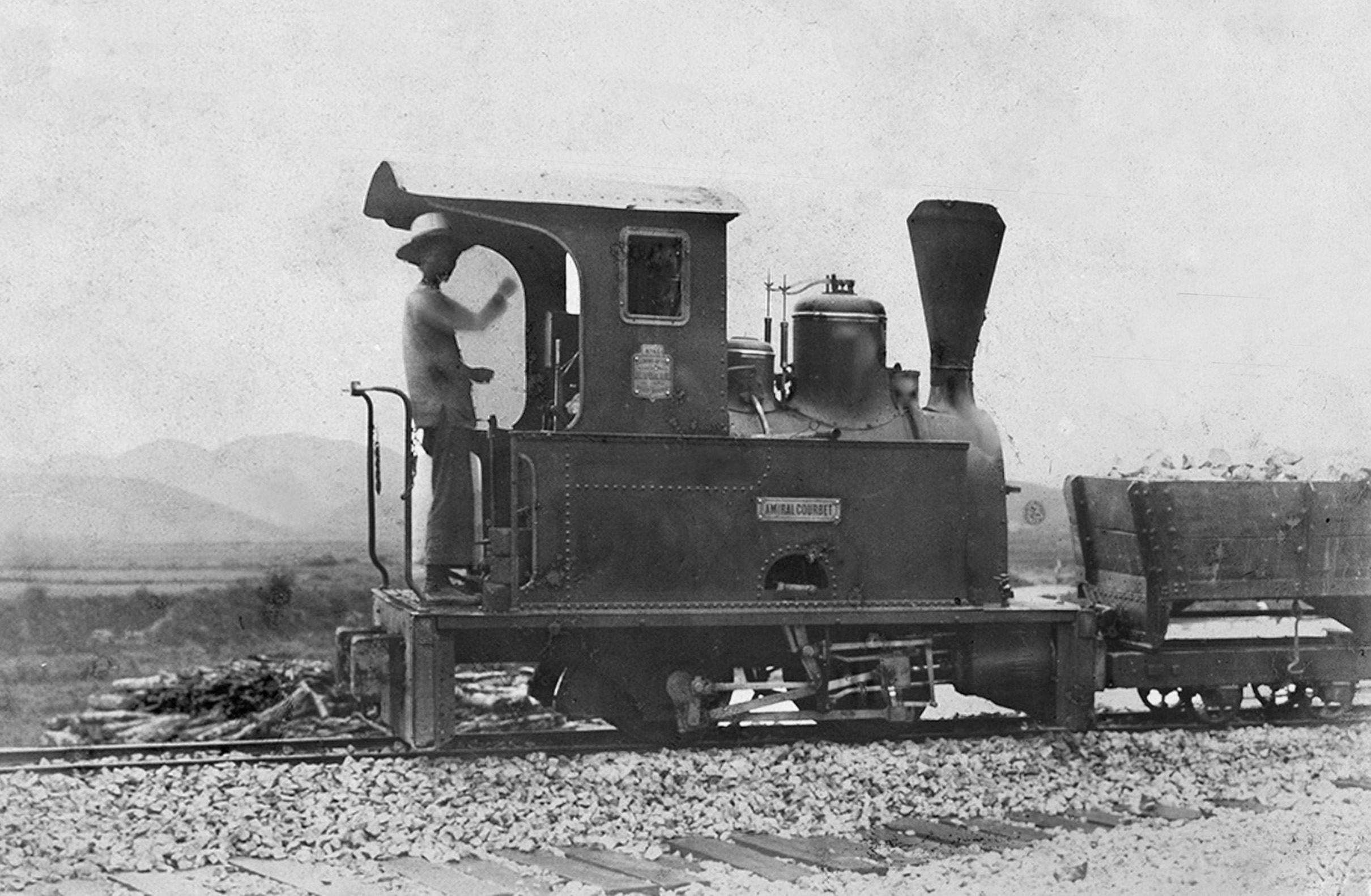

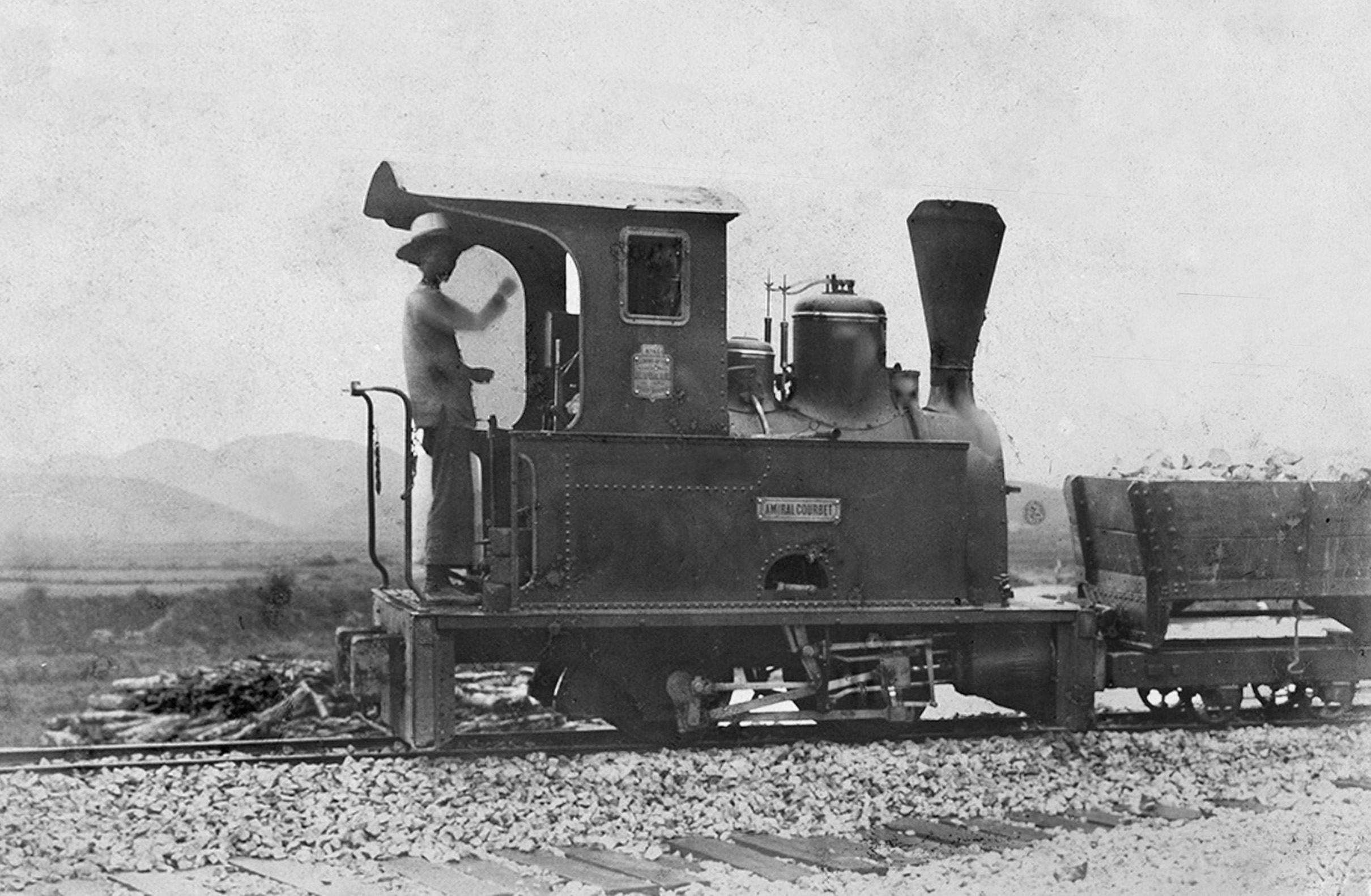

0.6m-gauge Decauville 4.5t 0-4-0T (020T) type 3 No 40 “Amiral Courbet” of 1887 hauls freight along the original Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn line, Vola Family Photos of Indochina around 1880, railroad building to Lang Son © Julie Vola

With financial problems increasing, Soupe agreed to forgo the “interested party” system and contract out some of the work. At the end of 1891, the Governor General of Indochina entrusted Vezin, a contractor from Hải Phòng, with the execution of the work on the Bắc Lệ line at a price of 73,000 francs per km; the contract stipulated that the line was to be completed by 14 July 1893. Once again, normal procedure was not followed; the Governor-General of Indochina entered into a mutual agreement instead of making an adjudication. Regarding the deadlines, the Protectorate was not, however, the loser in the affair; the section from Kép to Suối Ganh (19km) was opened on 5 October 1892, and that of Suối Ganh to Bắc Lệ (11km) was opened on 10 June 1893. Satisfied with this good result, the Governor General confided to the Entreprise Vezin the construction of the section from Bắc Lệ to Thanh Muôi, and then, on 17 February 1893, that from Thanh Muôi to Lạng Sơn, at a price of 71,600 francs per kilometre. This time, however, Vezin let things go a little; but was he the only one at fault? In 1892, Governor de Lanessan was able to observe “the total absence of studies from Bắc Lệ to Lạng Sơn; whatever may have been said in the past, these studies have never been done, this is admitted by the company itself ” (Report to the Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, 1 April 1892). Beyond Bắc Lệ, they entered a zone of active “piracy” and the works suffered. By June 1892, the correspondence of contractors in the Bắc Lệ region were already reporting numerous pirate attacks “which had long since caused considerable disruption in the works”… “the works were still suffering from the passage of pirates, who, having lost their food supplies in every encounter with our troops, then resorted to looting several construction sites, especially those of Cao Son and Sui Si Deo, where they took all the workers’ rice and killed three Chinese.”

The pirates were not the only problem; in April 1892, entrepreneur Eugène Leroy reported: “On the 7th instant, a team of 60 bricklayers was dispersed by the troops and seven workers were executed in the most summary fashion. While the troops kill my bricklayers by day, pirates set fire to my fuel supplies by night.”

Riots sometimes broke out on construction sites; in July 1892, Vezin was taken hostage by his Chinese coolies, whom he had refused to pay, although the affair settled down once the pay arrived. Survival soon became the main concern of the workers; an engineer from the Fives-Lilles company, who was on a study mission between Hà Nội and Pac Lam from 8-20 December 1893, left a rather haunting description of his tour: “From Bắc Lệ, we passed in front of the heads of pirates who had just been decapitated, while the road was strewn with the corpses of coolies who died of fever and exhaustion on the railway construction sites, or of fatigue caused by the transport of food and ammunition.”

All these problems did not impress the Government General, which simply noticed that deadlines were not being respected. In November 1893, it sent to the contractor an official named Lerulle who was responsible for checking a number of unclear accounting issues.

In December 1893, Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies Lebon notified the Governor General of the decision taken by Parliament to abolish the method of payment defined by the Additional Act of 1889; regions must henceforth be established for further works, which would be paid directly out of the Protectorate’s own funds. Governor de Lanessan therefore turned to the Bank of Indochina which, along with four other banks, agreed on 9 July 1894 to make a loan of six million francs, repayable by annuities from the budget of the Protectorate; whatever the cost to the Governor General, this decision had become inescapable. On 25 May 1894, the Bắc Lệ-Sông Hóa section was opened for operation; and the arrival of new money activated the work on other sections. “During the month of June alone, work was carried out with exceptional activity” notes a report; in July, the Sông Hóa-Thanh Muôi section was inaugurated. There was now only one gap to fill, between Thanh Muôi and Lạng Sơn (29 kilometres).

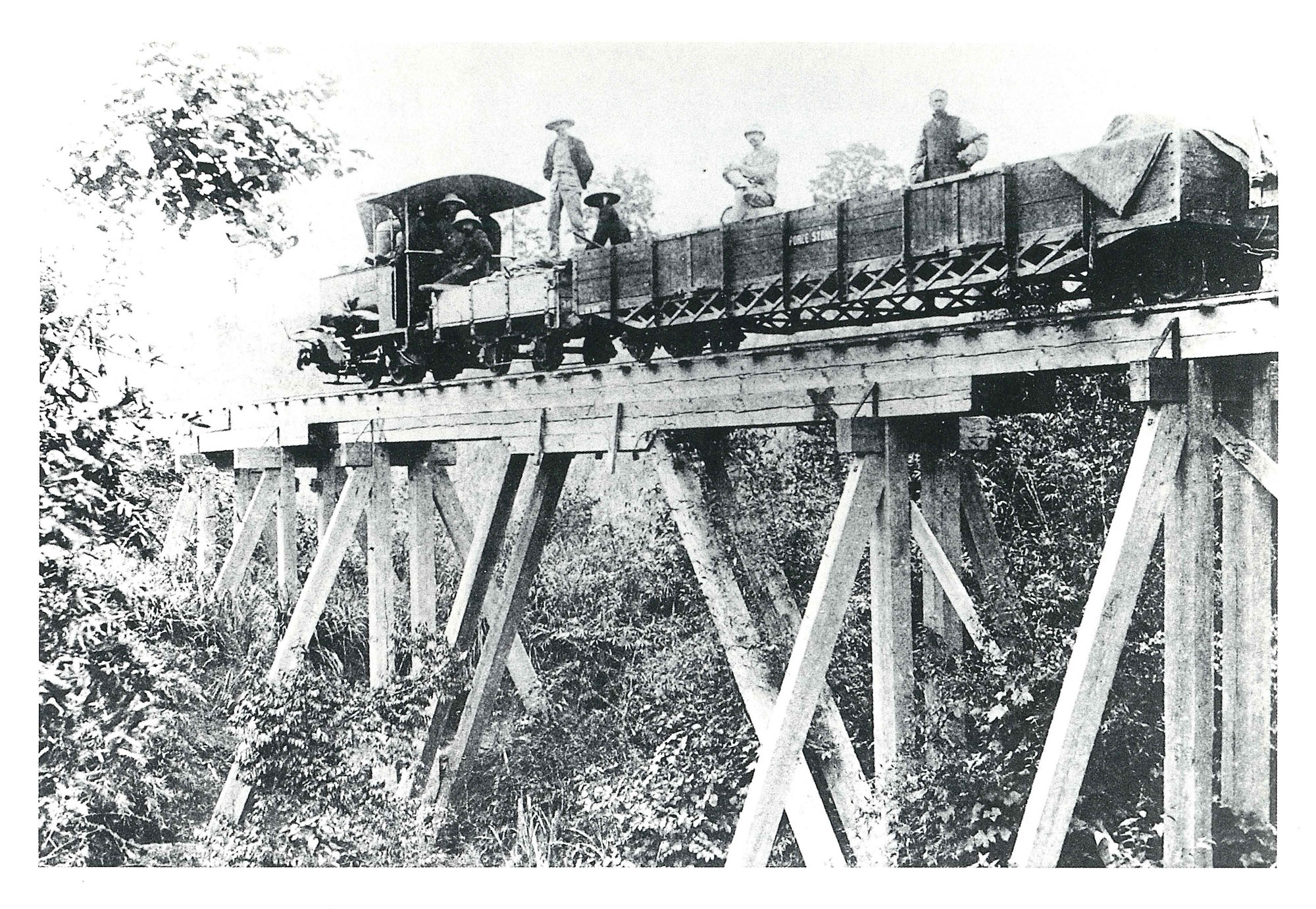

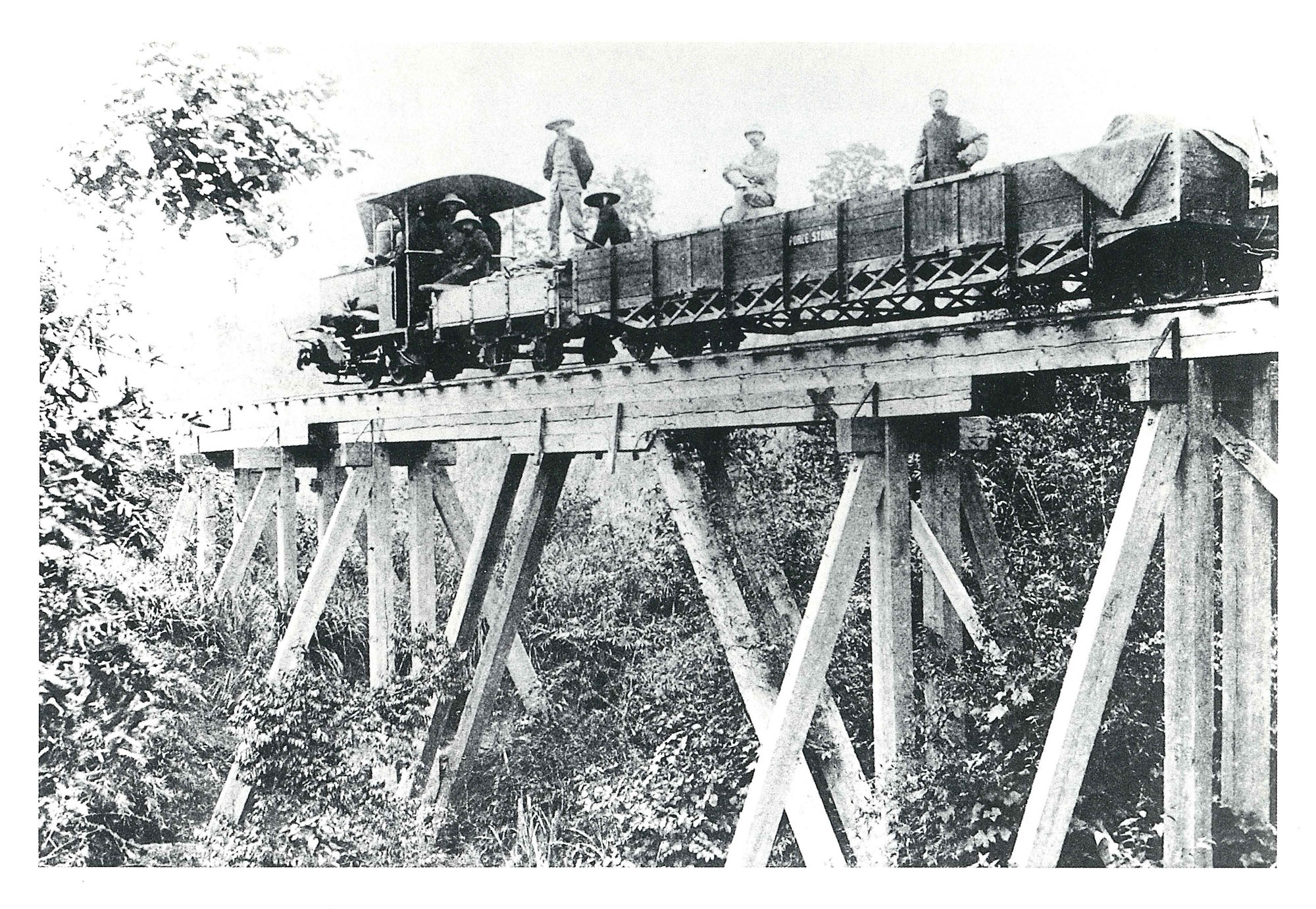

A train crosses a ravine on a magnificent wooden bridge. The train is made up of an 0-4-0T (020T) type 3 coupled to a small P series axled truck serving as a tender and a 4th class “passenger carriage” M505 being used as a wagon bearing the sign “Force 5 tonnes.” Collection C Daney

5 Discussions with China get underway

In September 1890, Soupe requested “the continuation of the line to the Chinese border gate.” He explained that “this addition is necessary since it would enhance the traffic on the Lạng Sơn line; the consequence would not only be a certain and immediate benefit for this line, but would also help to generate considerable foreign traffic to and from Guangxi.” When the convention of 3 November 1890 was ratified, Soupe inserted a clause stating that “in the event that the administration decides on an extension of the railway from Lạng Sơn to Na Cham,” they would “oblige themselves” to execute this line under the same conditions as that of the line to Lạng Sơn.”

Soupe returned to the charge in 1893, a time which saw him greatly agitated; he sent several engineers and representatives to Tonkin, “responsible for studying on the spot the proper means to activate the works.”

On the other hand, Soupe also obtained the contract for the construction and operation, at his own risk and peril, of the Phủ Lạng Thương-Hà Nội line. For Governor de Lanessan, this line “could be considered, strictly speaking, as a simple tramway.” A letter of 31 May 1893 announced to the adjudicators that they were authorised to begin studies for the extension to Na Cham; however, an agreement was signed the same day, authorising the transformation of the line to 1m gauge.

In 1894, a controversy broke out between the Under-Secretary of State and the Entreprise Soupe et Ravaud; the latter claimed that Minister of the Colonies Delcassé had approved the concession of a railway from Hà Nội to Phủ Lạng Thương and the border, and its transformation into a 1m gauge track. De Lanessan telegraphed: “Found no record of any documents relating to the draft railway contract.” And for good reason, since such a contract did not exist! Only studies of the route had been authorised. The exact role of the Governor General in this whole story is not very clear. In his memoirs, he claims that when he left Paris on 28 September 1894, he had, “in agreement with the Minister of the Colonies, prepared all the acts relating to the extension of the railway from Lạng Sơn to Hà Nội on the one hand, and from Lạng Sơn to the Chinese border on the other.” Did they try to remove an entrepreneur who was to say the least “indelicate”? This is what seems to have been confirmed by the following events.

6 Arrival of the railway in Lạng Sơn

Tonkin, 24 Décembre 1894 – Le premier train arrive à Lạng-Sơn

New entrepreneurs were chosen to complete the line (Entreprise Vola etc …). On the construction sites, fights and desertions were numerous, and the rare civilian supervisors could no longer cope with the situation; on Sunday 20 May 1894, the young Perigordian site foreman Marty was murdered as he tried to intervene in a fight. Military supervisors then made their appearance on the construction sites; at Khe Cai, more than 4,000 coolies were requisitioned; the arrival of this fresh workforce gave new impetus to the project, and it was then estimated that the line could be inaugurated on 1 January 1895.

On 24 December 1894, the railway finally reached Lạng Sơn, terminus of the line, at km 101. The future Marshal Lyautey, then just a humble commander, left us a description of the inauguration: “What a singular day, this inauguration of the railway! At six o’clock in the morning, we left Phủ Lạng Thương, a three-hour drive from Hà Nội. By two o’clock, we were in Lạng Sơn. The line was well guarded, that is true; on all the crests of this torn valley of Sông Thương, where the region of Cai Khinh evokes the wildest parts of Kabylia, there were watchtowers and blokhauses. Nevertheless, all along the valley, the line is now bordered by rice fields, which in the past year have replaced bush; villages have also sprung up near the railway in areas where, according to witnesses, not a single inhabitant would have been seen last winter. This was a pleasure train, carrying almost 200 passengers from Hà Nội, funny people without too many scruples, but alive, intelligent, and outgoing; we do not always know where they come from, or what criminal record they have, but nonetheless they do French work and bring their spirit and their endurance. Men in uniform, officers’ wives, officials in black clothes, this singular unpacking of transplanted French officialdom left again that night for Hà Nội, immediately after the banquet finished. All that was left were the two military staffs, those of the Governor and the General-in-Chief.”

Lyautey was not the only one to have noticed the sudden development of the regions crossed by the new line; In April 1894, while it was still under construction, Résident Supérieur Rodier had made the same observations: “Thanks to the presence on the line of such a considerable number of workers, the markets of the region, previously almost deserted, experienced for some time a significant growth. At Thanh Muôi, one could count from 4,000-5,000 natives from all parts of Tonkin. There were even Chinese coming from Longzhou.”

One could hear much the same story among the administrators living in the border region: “The establishment of the line, apart from the advantages for military transport, provides for the development of commercial affairs in the Lạng Sơn region.”

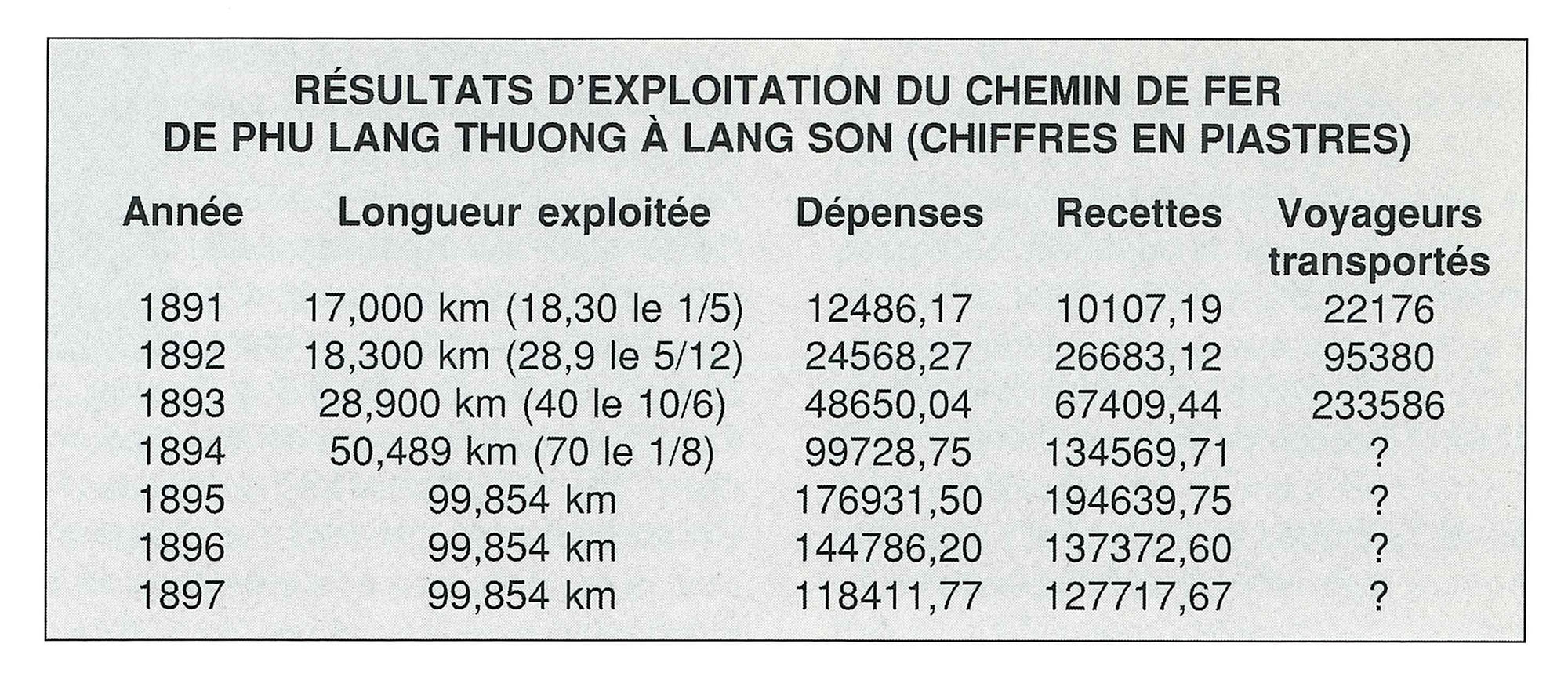

7 Operation

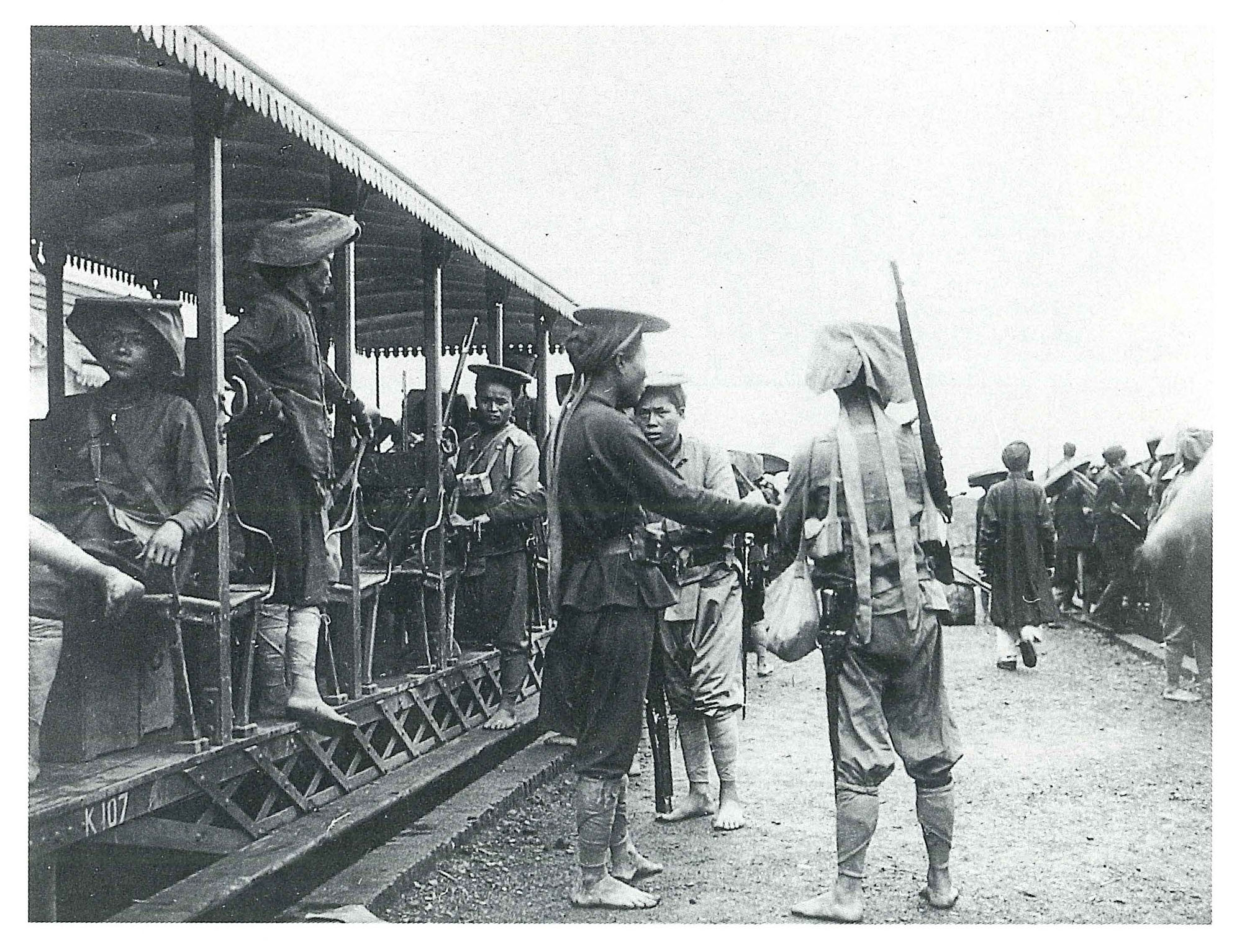

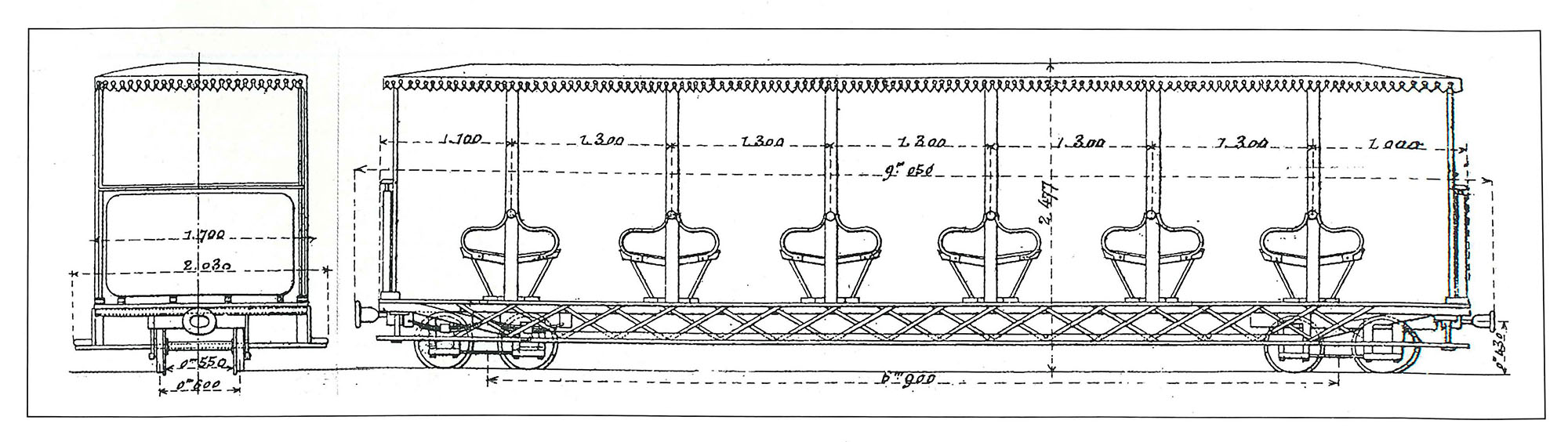

Station interchange: a squad of Annamese riflemen board a 3rd class type Ke Decauville “Exposition de 1889” carriage

The endemic disturbances which bloodied the region would not fail to affect the railway; if, in many places, they had built small blokhauses intended to protect the line, this was not the case along the whole of its course. On 17 September 1894, at PK72, the Cai Khinh pirates attacked a train in the Cao Sơn cutting. The driver calmly backed up the train to Bắc Lệ station, thereby avoiding a massacre. The next day, the railway again fell prey to the “pirates,” but this time it was much more serious, as a journalist of the time told us:

“Public opinion was already overexcited by the stories of attacks by pirate bands when a new atrocity took place on the Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn, this time in broad daylight and within rifle range of the innumerable squads of police troops which guard the railroads, increasing the consternation and anger of our colony, which was so badly guarded and so insufficiently defended. On 18 September, a dissident group led by Ly Ke Koa caused the derailment of a train on the Phủ Lạng Thương line, a little beyond Suối Ganh station. Fortunately, this derailment did not have lamentable consequences. But in the midst of the disorder caused by the accident and the death of the Chinese mechanic, killed on his machine, the bandits jumped onto the carriages, looting goods and taking many prisoners, among whom were two Europeans, MM Chesnay, entrepreneur, and Logion, a Greek subject who was his employee (NDLA: in 1884, Chesnay had founded the newspaper l’Avenir du Tonkin). After this audacious coup de main, accomplished in the full light of day, the bandits retired to the Cai Khinh massif, where, out of reach of our blows, they established their inaccessible lair. A French column, under the orders of the intrepid Colonel Galliéni, set out in pursuit of them.”

Gradually, however, the “pacification” progressed; By 1897, the region was more or less secure, after the submission of the borderlands pirate chief A Coc Thuong. A few months later, Đề Thám and Lương Tam Kỳ (Thái Nguyên province) would also submit.

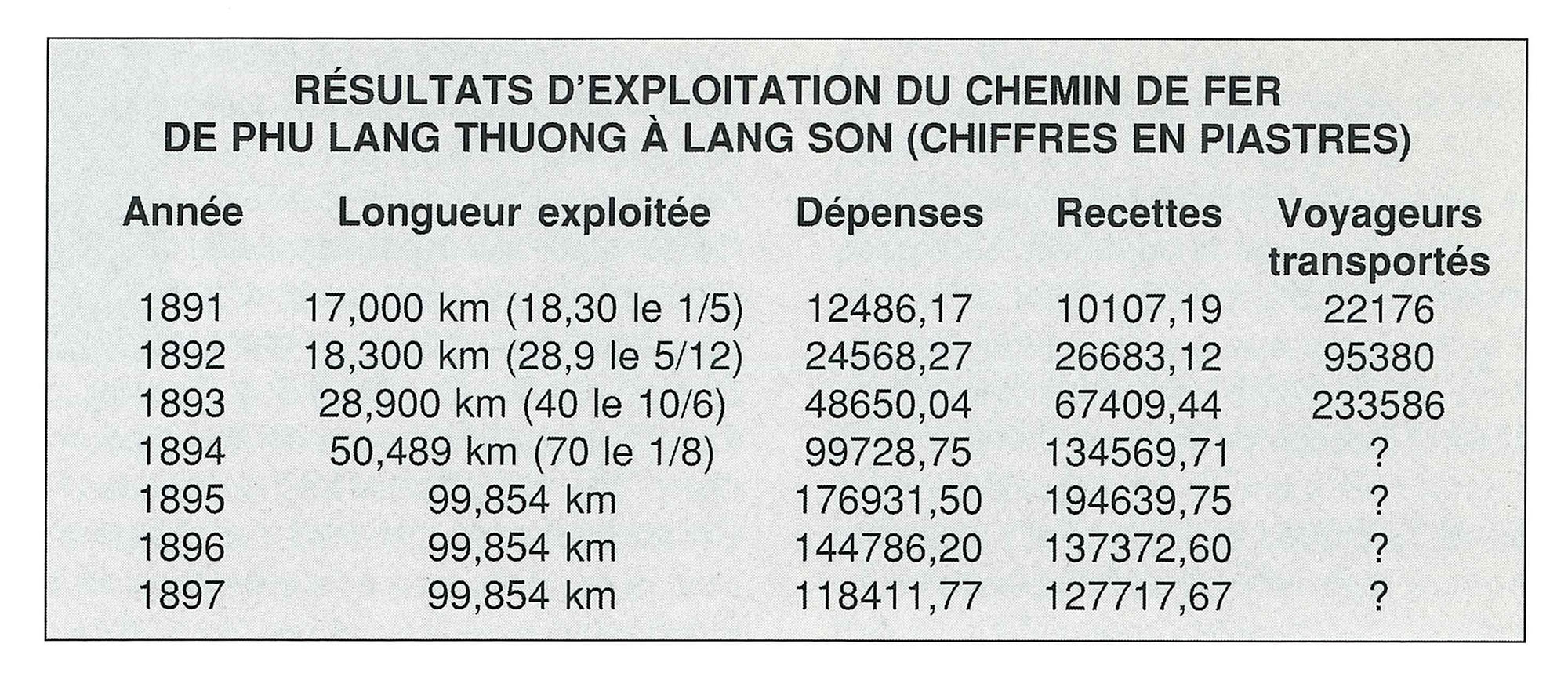

But by this time Lạng Sơn’s Decauville line was already condemned. At the time the line was inaugurated, some small works still had to be completed, but the whole could be considered finished. If we exclude the few reports which show the impact of the railway on the regions crossed, all judgments made on the Decauville line had been negative; very quickly, the engineer Prévot would complain about the excessive number of European officials on the line, which had unnecessarily increased operating costs. An attempt was made to replace this personnel with local people, who the French authorities nonetheless distrusted: “We can arrange the internal service of the stations in such a way that the natives do not have to handle money.”

But it was above all the conditions of the line that were the object of criticism: “The railway from Phủ Lạng Thương to Lạng Sơn had to be operated first of all under very onerous conditions … We know how it was built; the equipment delivered to operate the line was insufficient, and already tired by the effort of construction “(Report of Rénaud, Director of Public Works, 1898). General Ibos, who found this railway “ridiculous” (an opinion he shared with Paul Doumer), preferred to speak of a “Decauville at 400,000 francs per kilometre.” It should be noted that the USP of the Corneil firm was that “a Decauville railway, with its locomotive, three-classes of carriages and freight vans, costs only around 10,000 francs per kilometre. That’s almost nothing.”

8 Rolling stock

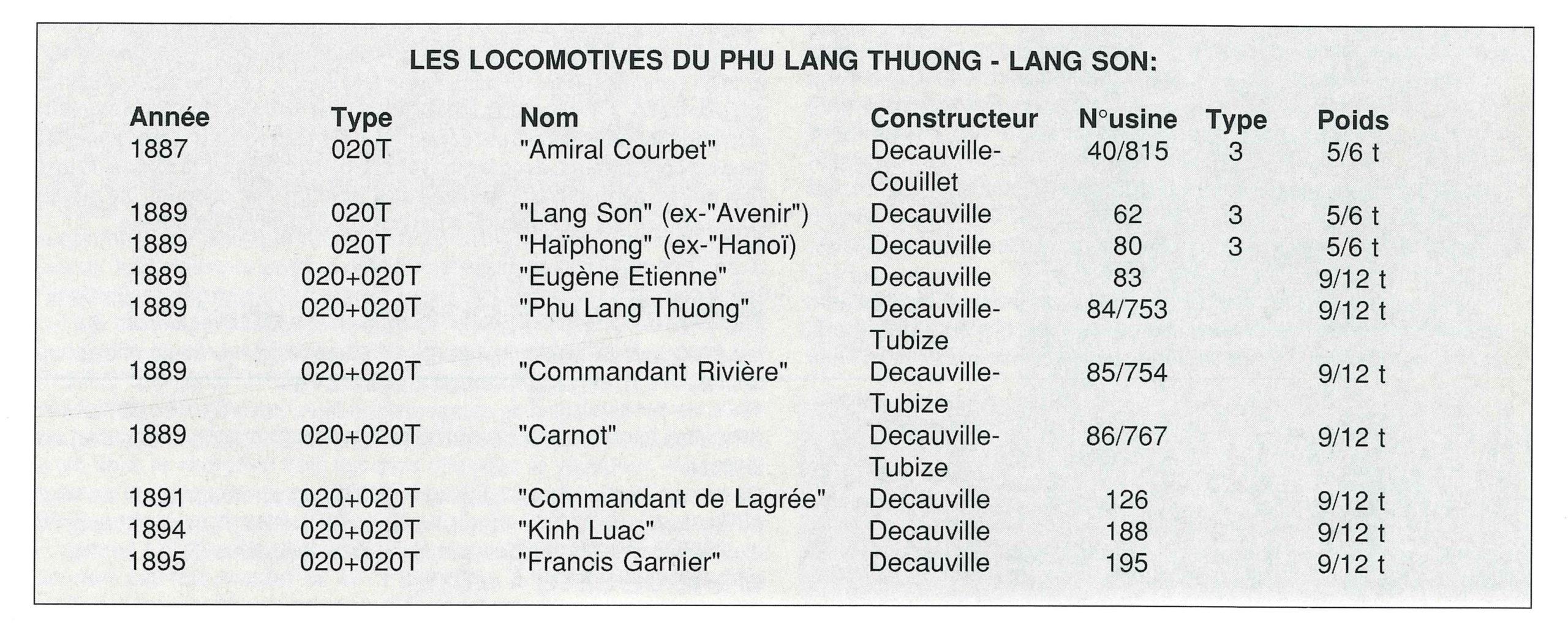

8.1 Locomotives

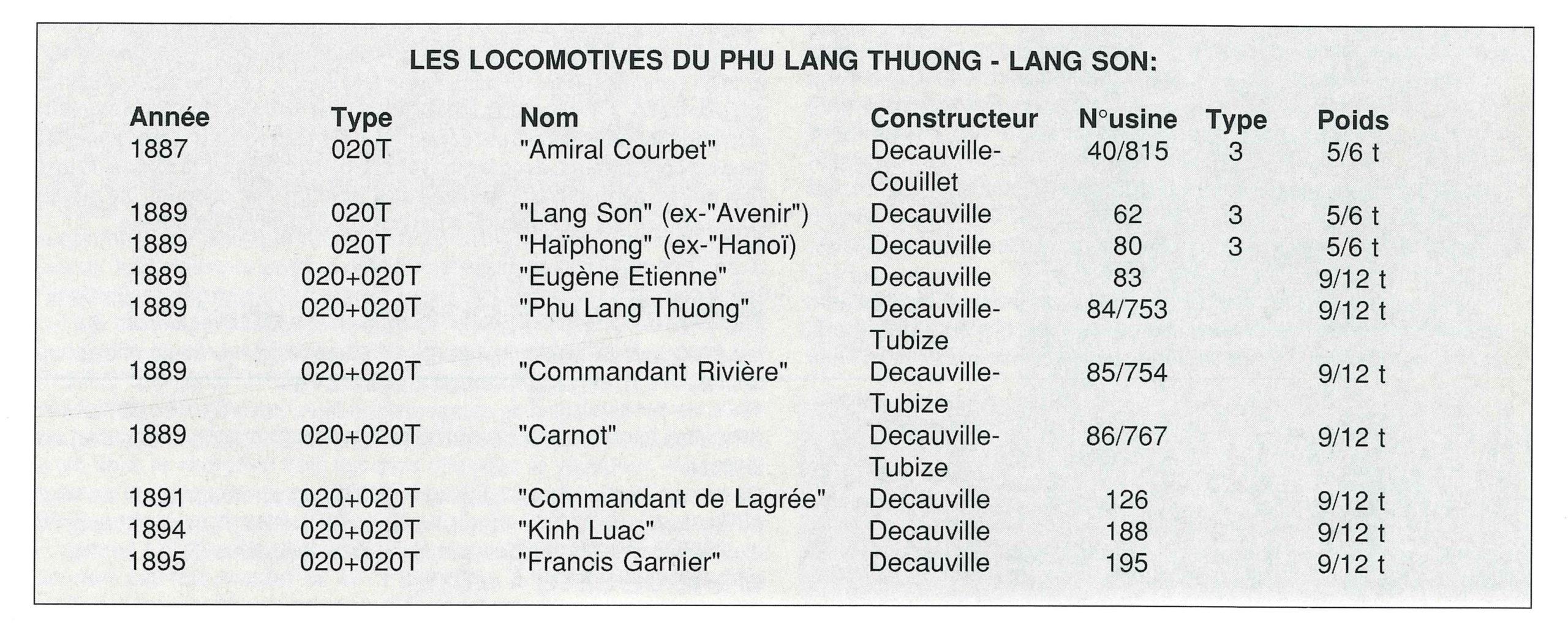

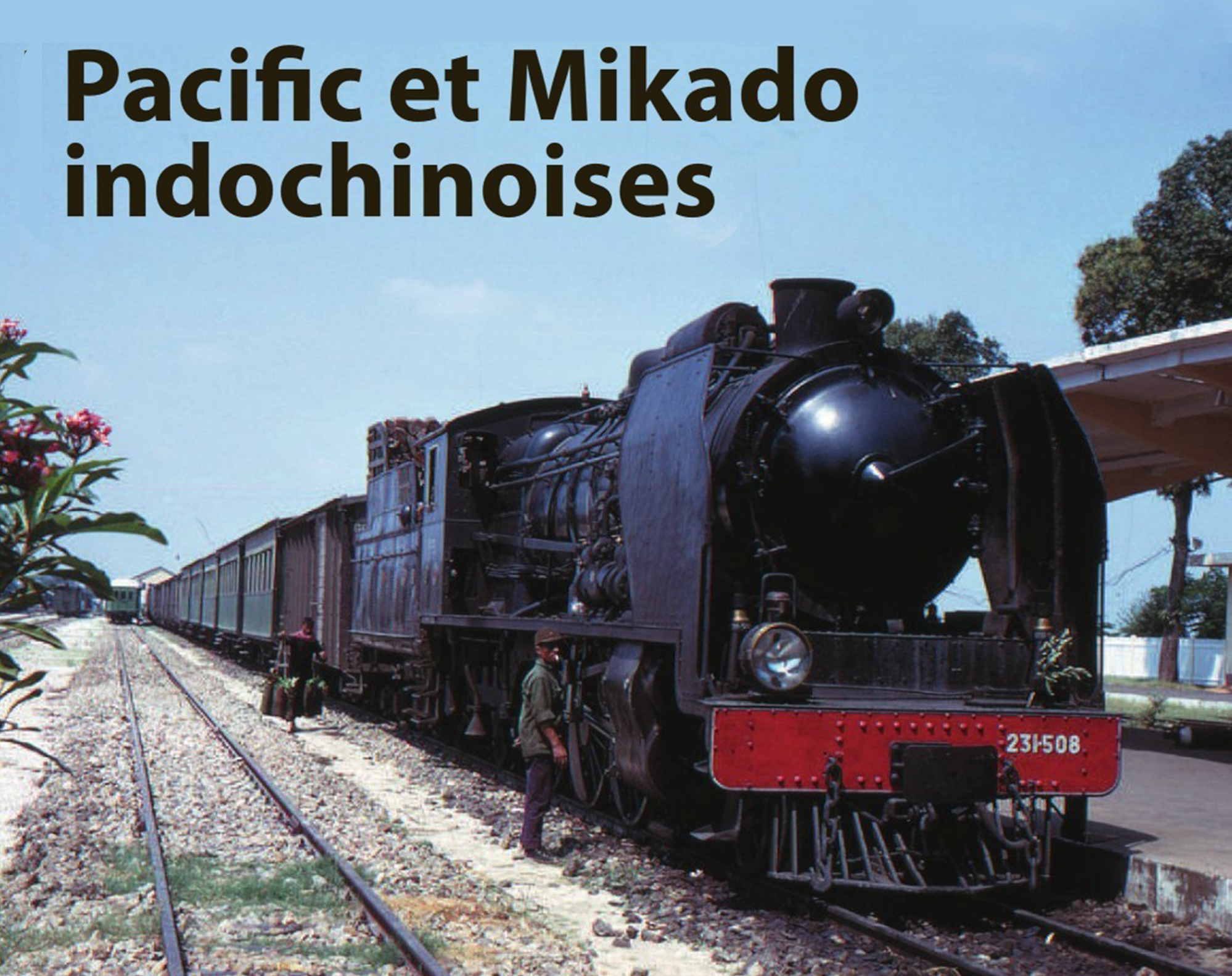

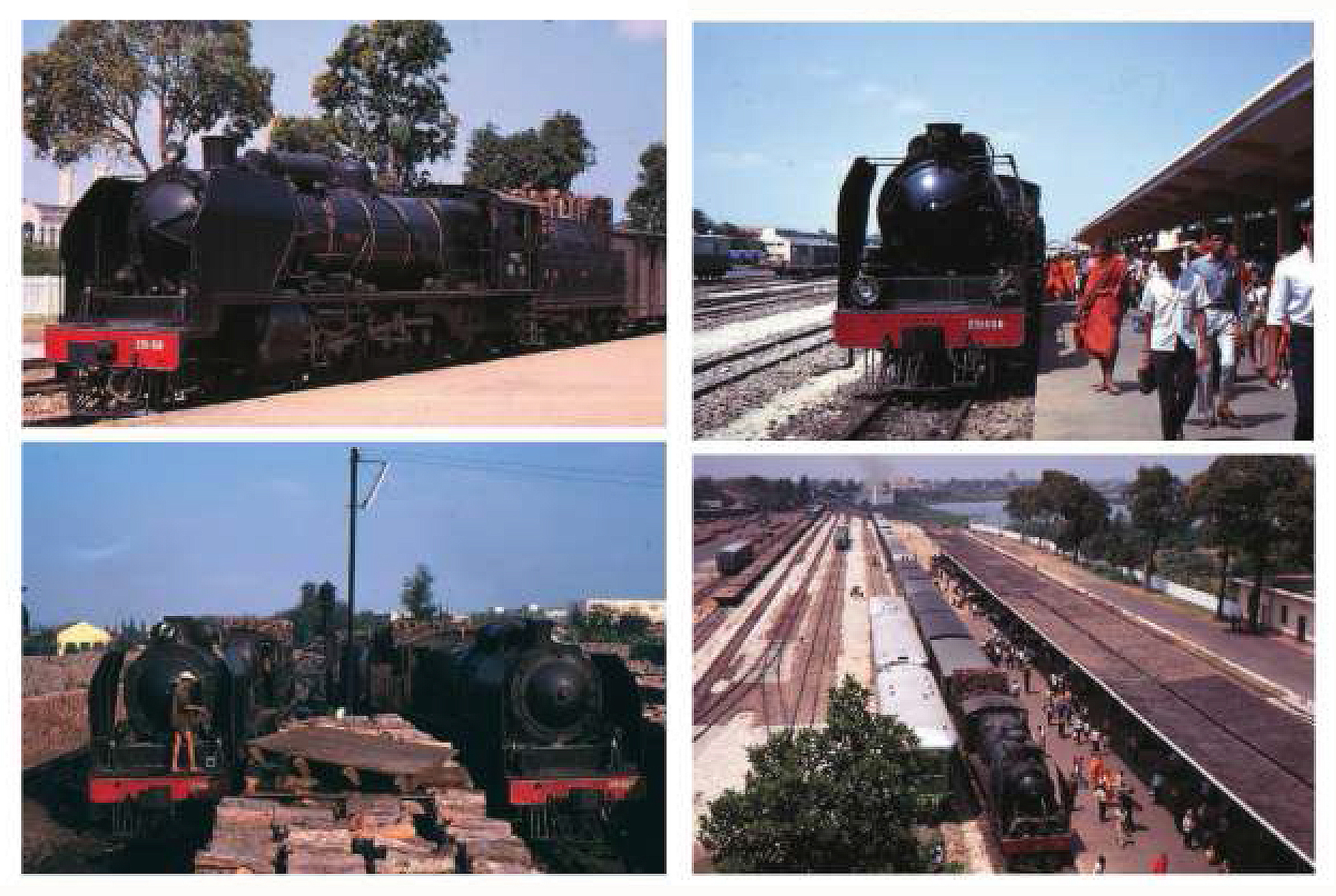

Six locomotives were delivered by Decauville in 1890: the three small 020Ts, Nos 40, 62 and 80, as well as three articulated compound Mallet 020 + 020T machines (Decauville Nos 84, 85 and 86). Only the 020T No 40 was delivered first to Hà Nội. All other machines were delivered directly to Phủ Lạng Thương. The 020T No 62 “Lạng Sơn” (ex- “l’Avenir”) came from the Universal Exhibition of 1889 and probably also the 020T “Haiphong” No 80. Two other locomotives would be delivered under a contract of 18 May 1891: they were Mallet 020 + 020T locomotives of 9.5 tonnes, equipped with corresponding tenders (Decauville Nos 83 and 126). A sixth Mallet locomotive would be supplied by Decauville in 1894; this machine, which appears on the network rolling stock reports for July 1894, carried the Decauville No 188.

It seems that the Phủ Lạng Thương railway never owned more than seven Mallet locomotives. Some of the machines were fitted with tenders, definitely the last three, which were coupled to tenders Nos 4, 5 and 6, however, were these the first three thus equipped?

8.2 Hauled rolling stock

We don’t really know what the original hauled stock was, but it quickly became insufficient. In January 1891, a number of wooden waggonets were purchased locally for the sum of 16,000 piastres; they were intended for the transport of ballast. Additional material was delivered under the contract of 18 May 1891; it consisted, according to the Decauville classification, of:

– 36 type T wagons with tipping body

– 15 type T wagons with tipping body

– 51 type Pp gondola wagons

– 9 type Pp wagons with screw brake

– 12 type 60c wagons

– 12 type 60c wagons with screw brake

The state of the network material in July 1894 mentions the existence of the following material:

– 1 salon car No S1

– 2 mixed cars of 1st/2nd class series AB1 and 2

– 2 mixed cars of 2nd/3rd class series D3 and 4

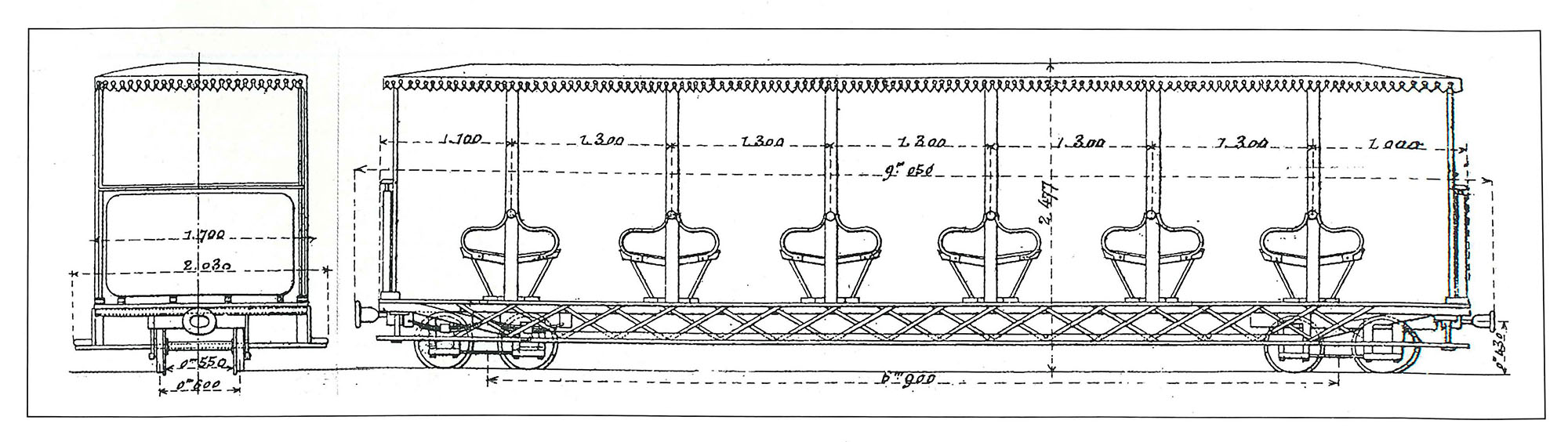

– 13 cars of 3rd class series KC 101 to 113

– 6 cars of 4th class series MC501 to 506 (a photo shows the M507)

– 6 vans of series L 401 to 406

– 60 series P and Pb gondola wagons

– 8 flat wagons series Mp1 to 8

Subsequently, the network completed its equipment:

– flat wagons series Mp 9 to 12

– wagons series Mv 13 to 16

– transformation of the Ke 104 car into a mixed baggage-mail van Kp 104

Vue d’une petite locomotive à vapeur, quelque part au Tonkin, Fonds ASEMI, showing a 0.6m-gauge Decauville 5t 0-4-0T (020T) type 3 locomotive

9 In conclusion

The arrival of Paul Doumer in Indochina and the development of the concept of the Transindochinois (North-South line) would sound the death knell for Lạng Sơn’s Decauville railway; in 1896, two years after the inauguration, its transformation into a 1m gauge line began.

In the same year, in New Caledonia, the construction of a railway between Nouméa and Bourail was envisaged. Not knowing which system to use, the Governor of New Caledonia asked for information on the 0.6m track used in Tonkin. The Governor General of Indochina advised strongly against the use of Decauville equipment, because “the results provided by the 0.6m track were not satisfactory.” For Decauville, the Tonkinese experience therefore ended in failure, which explains the little obvious interest in this system in our French colonies.

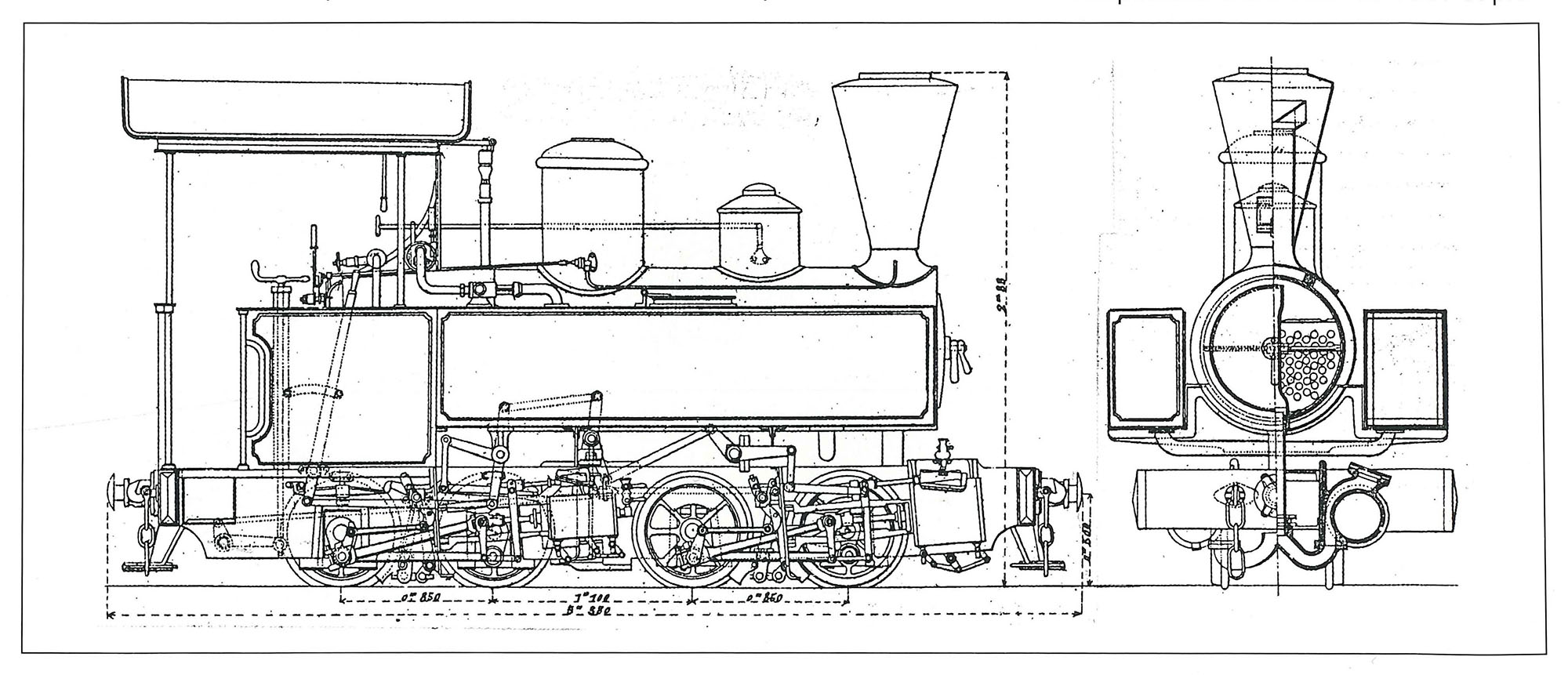

Drawing of a Decauville 020T type 3 of 5 tonnes, identical to Nos 40, 62 and 80, used with or without tender, Collection J Thévenin

Diagram of Decauville Mallet 020 + 020T locomotives Nos 83 to 86, 126, 188 and 195, used on the Phủ Lạng Thương-Lạng Sơn line, where they were equipped with a tulip coupling instead of a central buffer and chains; they were also harnessed to a tender similar to that of the 020T type 3. Collection J Thévenin

Diagram of Decauville carriages with Ke type “1889 Exhibition” bogies, Collection J Thévenin

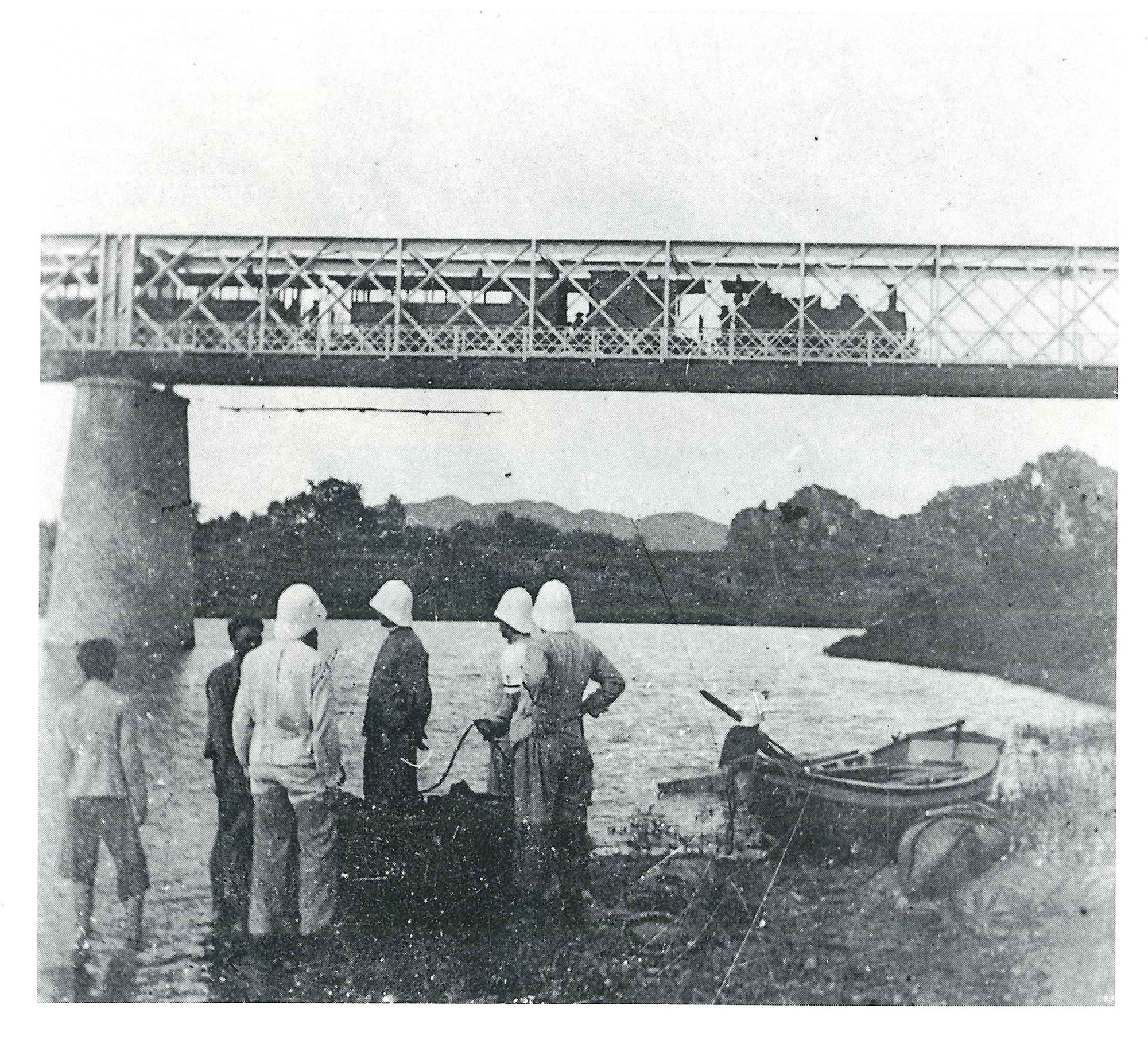

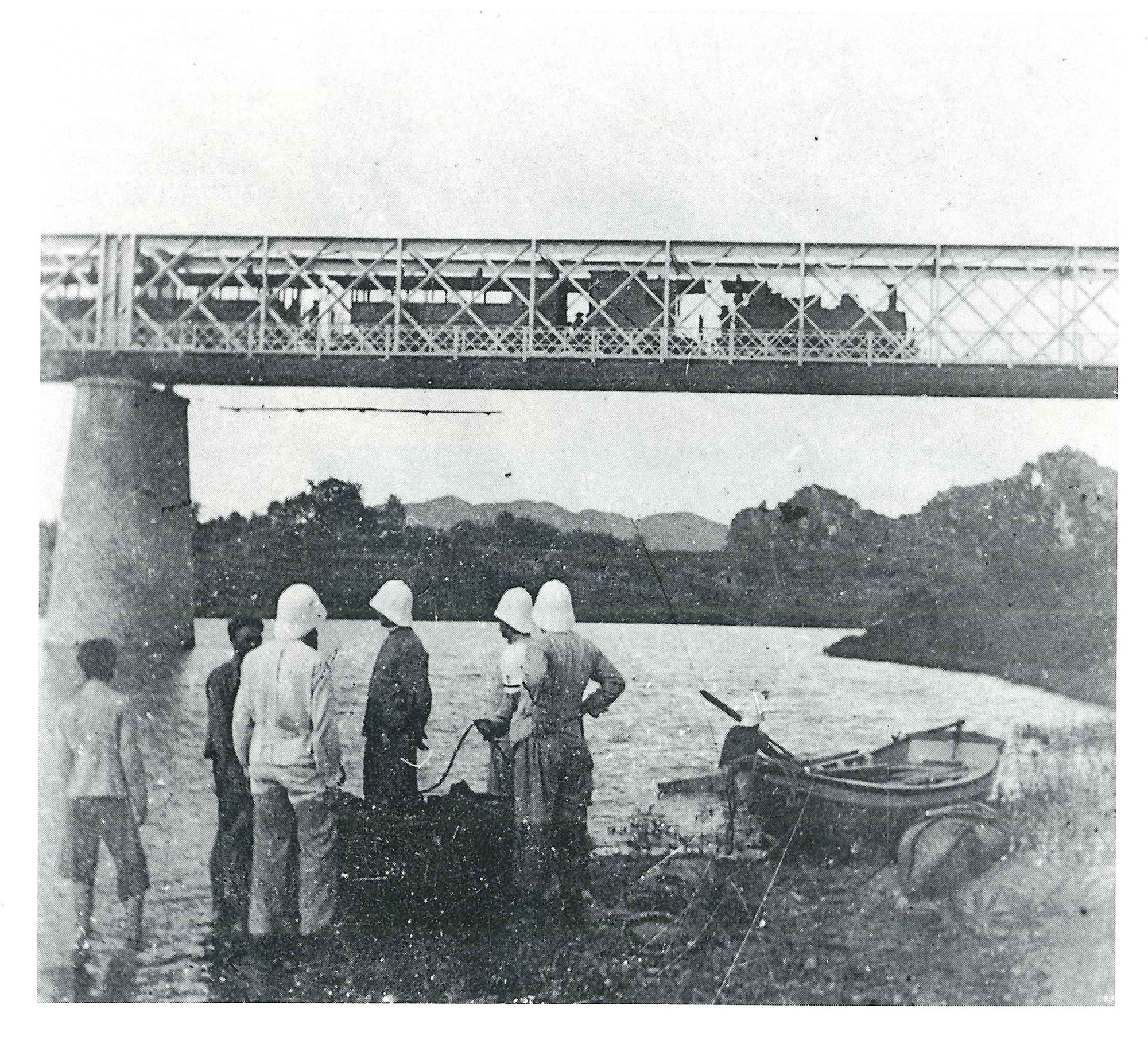

The 0.6m track eventually disappeared and was replaced by the 1m gauge track: here in 1902 is the inaugural train of the new Lạng Sơn-Đồng Đăng section crossing the new metal bridge at Kỳ Lừa, with a Weidnecht 130T series 650 locomotive at the head.

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, 2012) and the guidebooks Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018), Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019) and Exploring Quảng Nam (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2020).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

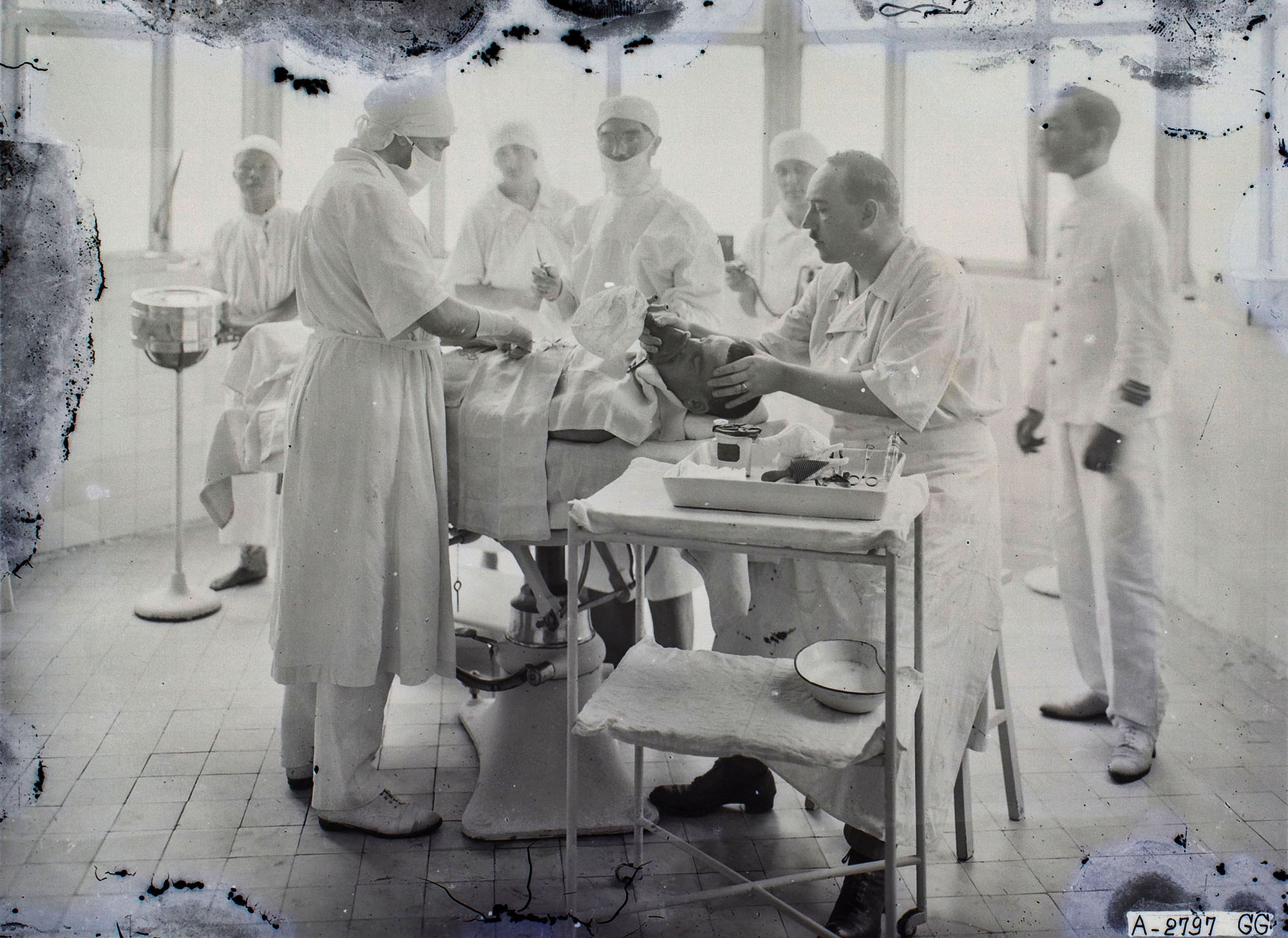

The flu made its appearance in July 1918 in the various territories of the Indochinese Union.

The flu made its appearance in July 1918 in the various territories of the Indochinese Union.

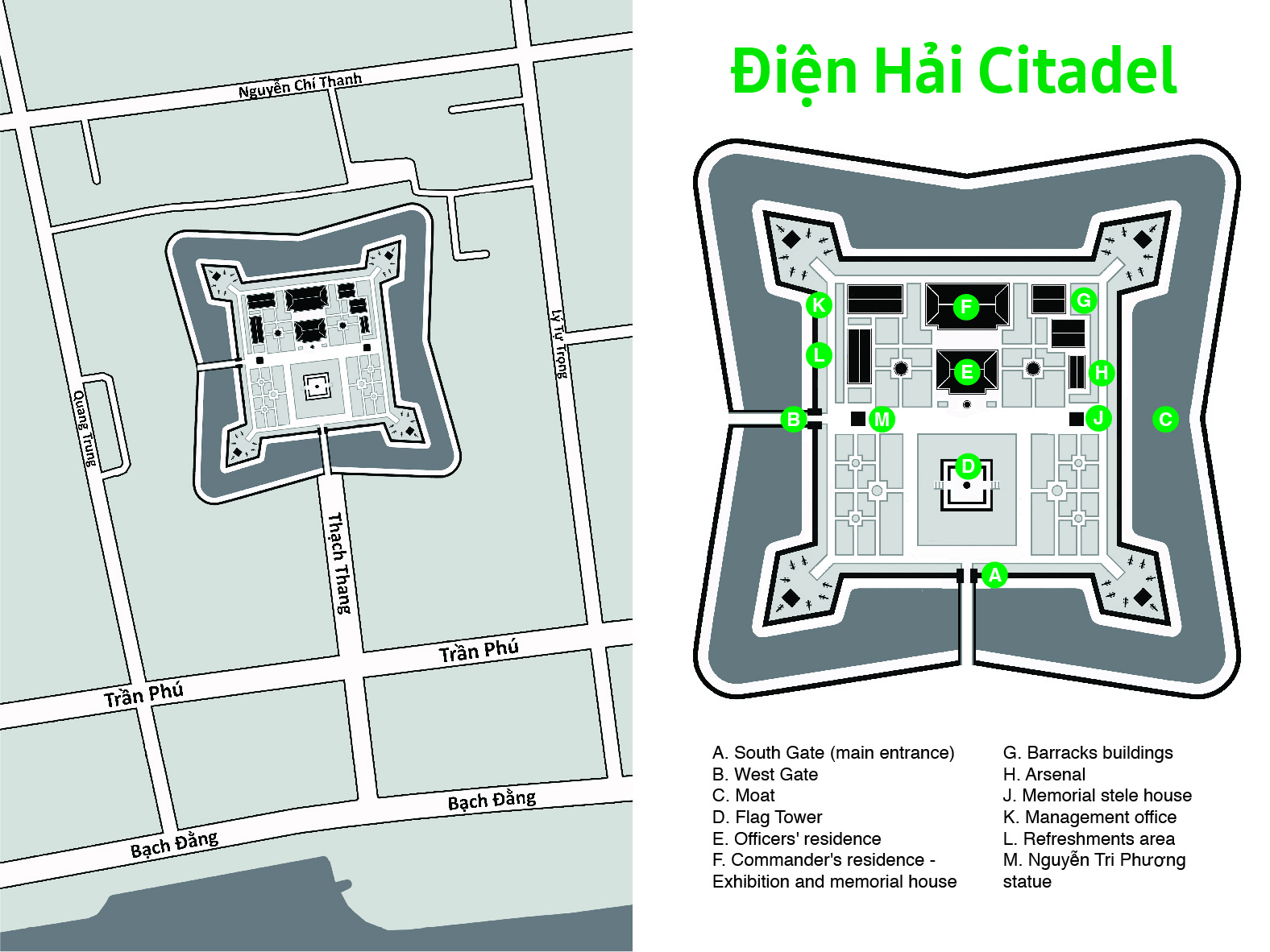

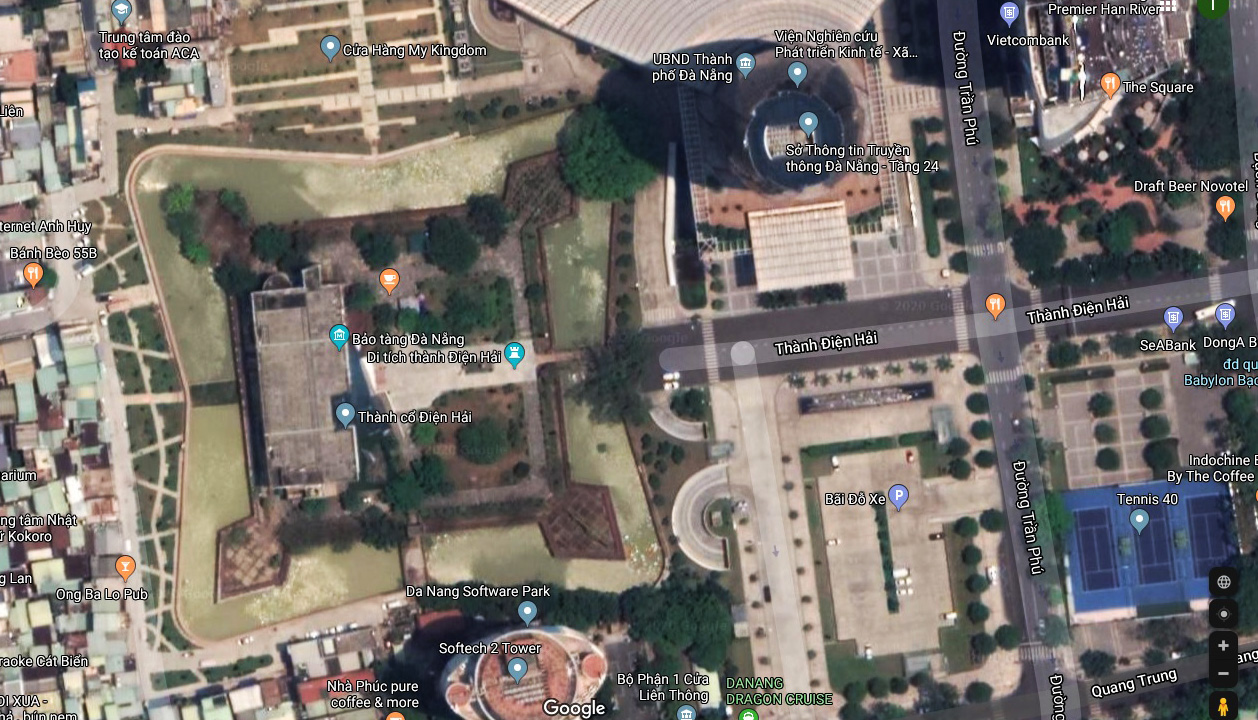

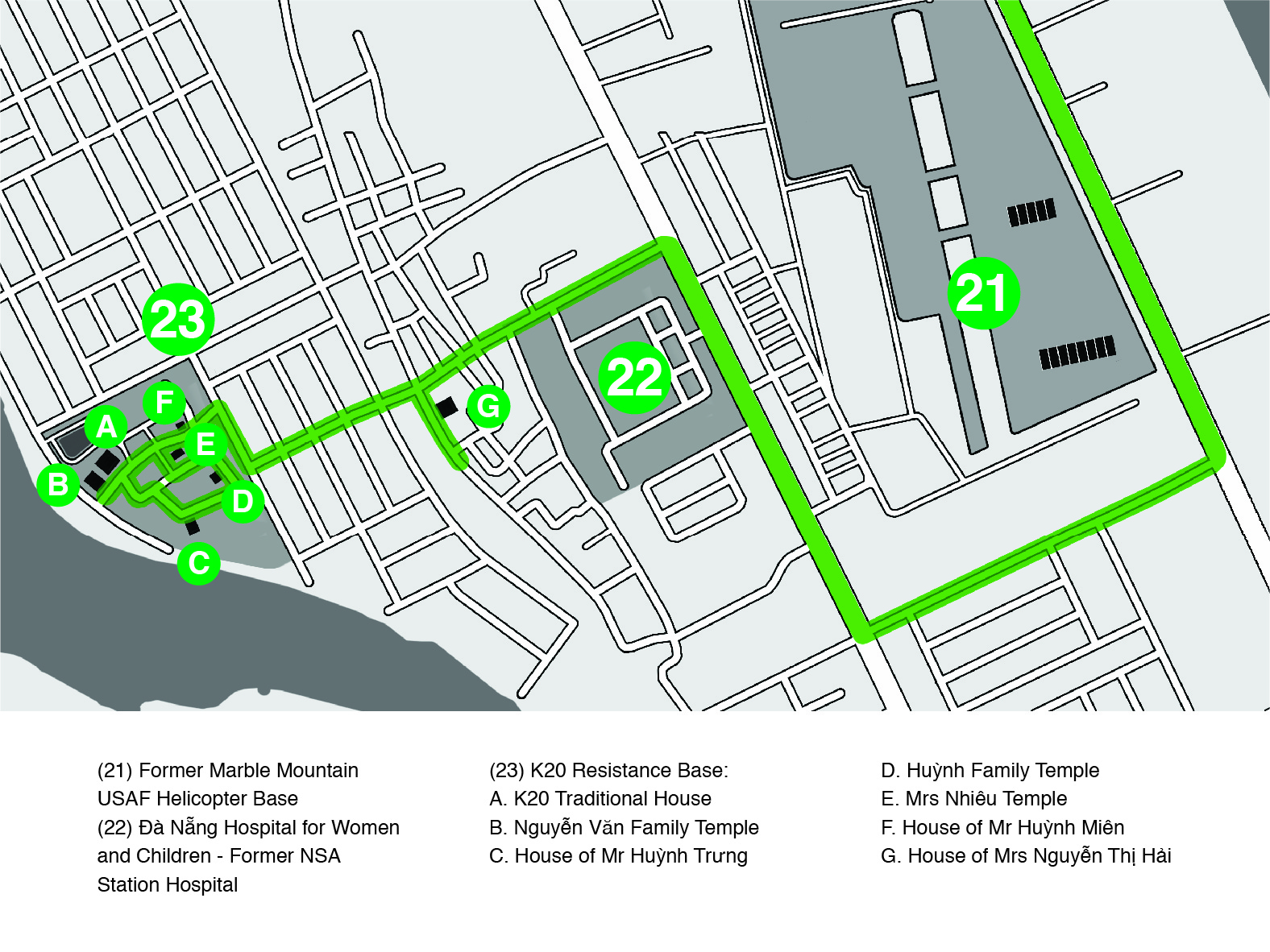

Many Đà Nẵng visitors and residents are familiar with the old Nước Mặn helicopter base (21 on the map above), which is situated next to the Đà Nẵng-Hội An road in Ngũ Hành Sơn district.

Many Đà Nẵng visitors and residents are familiar with the old Nước Mặn helicopter base (21 on the map above), which is situated next to the Đà Nẵng-Hội An road in Ngũ Hành Sơn district.