A Société Ernest Heckel “metallic cabin” aerial tramway system operating in Europe, 1934

With the construction of cable car systems currently all the rage in Việt Nam, perhaps this is an opportune time to tell the story of Việt Nam’s first public aerial tramway system.

In recent years the cable car has become increasingly synonymous with tourism in Việt Nam. From Vũng Tàu to Đà Lạt, from Nha Trang to Ba Na, it seems that no mountain landscape is complete without their omnipresent gantries and cables. Love them or hate them, by 2015 it will even be possible for tourists to take a cable car through the pristine mountain landscapes of Sapa.

The earliest forms of aerial tramway used in Việt Nam were téléphérique systems installed by the colonial French authorities at coal mining installations in Tonkin (Quảng Ninh) and Annam (Quảng Nam). However, before the 1930s there is no record of aerial tramways being used in Indochina as a means of public transportation.

All this changed in 1933, when funding for a new Việt Nam-Laos rail link through the Mụ Giạ border pass (modern Quảng Bình province) dried up and an aerial tramway built to carry construction materials to the chantiers was pressed into passenger service.

Back in 1898, the French had shelved the idea of building an “inland” rail link from Saigon to Hà Nội in favour of a coastal route, but as the Transindochinois railway line neared completion in the 1920s, a group of ministers in the administration of Governor General Martial Henri Merlin (August 1922–April 1925) began to lobby for the construction of a second rail route through the interior, with the aim of connecting Saigon and Hà Nội with Cambodia (Stung Treng and Kratie) and Laos (Thakhek). The idea was given added impetus in 1922 when tin deposits were discovered along the projected route in the Nam Pathene valley.

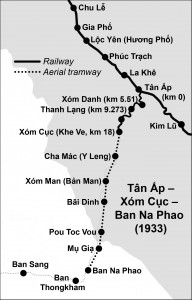

In 1927, plans were drawn up to build a preliminary 187km section of the new line from Tân Ấp junction (a main line station south of Vinh in rural Quảng Bình province) to Thakhek in Laos. The Saigon-Lộc Ninh “rubber line,” then under construction in Cochinchina, was envisaged as the future southernmost component of the same line.

A rare shot of the aerial tramway (photo credit: http://fer-air.over-blog.com/)

With the Siamese eventually expected to extend their rail network as far as Nakhon Phanom and Thakhek, proponents of the new line began to wax lyrical about a future “great international line” connecting Singapore with Paris. So enthusiastic were they that in 1927 they even delayed work on the final section of the Transindochinois, in order that preliminary planning of the new inland line could get under way.

Construction began simultaneously in 1929 on two separate stretches — from Tân Ấp to Xóm Cục (18km) in Annam, and from Thakhek to Pha Vang (16km) in Laos.

In parallel with these works, in order to increase the capacity of the service road in the mountainous border area, a 39km aerial tramway was built to link Xóm Cục with the Ban Na Phao frontier post in Laos. Funded by Germany as part of its war reparations programme, the construction of the aerial tramway was entrusted to the Ernest Heckel Company of Sarrebruck (founded 1781), which had recently made a name for itself by installing its famous “metallic cabin” systems in several up-market European ski resorts. When it was inaugurated in 1931, it was said to be the world’s longest aerial tramway line, with seven stops—Xóm Cục (Khe Ve), Cha Mác (Y Leng), Xóm Man (Bản Man), Bãi Dinh, Pou Toc Vou, Mụ Giạ and Ban Na Phao.

Xóm Cục Station with the connecting aerial tramway in the background (photo credit: http://fer-air.over-blog.com/)

Construction of the railway line proceded slowly, and the first 18km section from Tân Ấp to Xóm Cục did not open to traffic until 13 September 1933. There were only four stations – Tân Ấp (km 0), Xóm Danh (Thanh Thạch, km 5.51), Thanh Lạng (km 9.273) and Xóm Cục (Khe Ve, km 18). The railway line incorporated two tunnels at Thanh Lạng (334.32m) and Xóm Gi (70.38m), two iron river bridges and three brick viaducts of 39.72m, 56.72m and 65.76m respectively.

The 16km stretch of railway line built on Lao territory incorporated two viaducts and four stations—Thakhek (km 0), Ban Tham (km 7.44), Ban Nam Don (km 10.3) and Pha Vang (km 15.59). However, although construction of the Lao section is known to have reached an advanced stage, there is no evidence that it was completed or that trains ever ran on it.

By this time, critics of the “inland” railway scheme had gained the upper hand within the colonial administration, and against a background of financial crisis and growing political insurgency, funds to build the remainder of the line were diverted for use in other areas.

This mystery locomotive being unloaded from a ship on the Long Đại river (Quảng Ninh district, Quảng Bình province) onto the main North-South line in 1930 is believed to have been destined for the ill-fated Tân Ấp–Thakhek branch line

With no more money available to complete the railway line, the authorities stopped work on it and instead opened the aerial tramway to public service with effect from 18 December 1933.

Thereafter, the 18km railway line from Tân Ấp to Xóm Cục and the connecting 39km aerial tramway from Xóm Cục to Ban Na Phao became an important cross-border route for both passengers and freight, administered as an integral part of the colonial railway network Chemins de fer de l’Indochine. In the period from 1 November 1936 to 30 March 1937, it is said to have conveyed 1,197 tons of goods from Việt Nam to the Lao border and 348 tons in the other direction.

In October 1937, plans to build the remainder of the railway line were definitively abandoned by the French authorities. Although revived in 1942–1945 during the Japanese occupation and again briefly in 1948 by the French, they would ultimately come to nothing.

Passengers changing from train to the Thakhek bus at Xóm Cục Station in 1934 (photo credit: http://fer-air.over-blog.com/)

The extraordinary combined railway/aerial tramway service from Tân Ấp to Ban Na Phao continued in operation until 1947, when both railway and cableway were destroyed by the Việt Minh. Today, little remains of the original infrastructure other than the overgrown bases of old aerial tramway gantries, ruined railway viaducts, collapsed tunnels, and at Khe Ve (formerly Xóm Cục) the sole surviving metal railway bridge built by the Société Levallois-Perret.

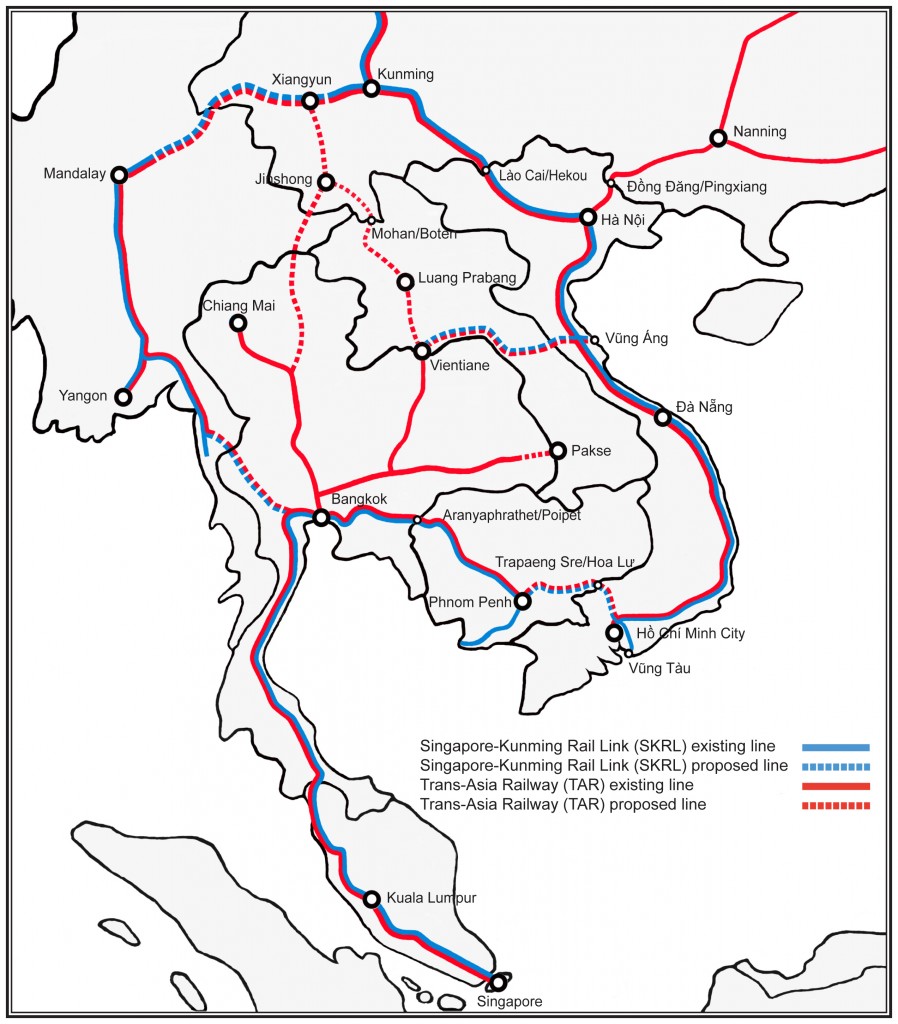

Almost 70 years after the Tân Ấp–Thakhek railway line project was abandoned by the French, there are signs that the “great international line” from Singapore to Paris envisaged by Merlin’s ministers may one day become a reality as part of the Trans-Asia Railway (TAR) and Singapore-Kunming Rail Link (SKRL) schemes. In 2003 the governments of Việt Nam and Laos signed an agreement on Economy, Culture, Science and Technology in which the two sides pledged to build a rail link from the Lao capital of Vientiane to the coast of Hà Tĩnh Province in Việt Nam – via the Mụ Giạ Pass. Travelling via Thakhek and then following the route of the abandoned Tân Ấp–Thakhek branch, it will meet the North-South (and future SKRL/TAR Singapore-China) line at Tân Ấp junction and then continue eastward to Vũng Áng deep water port. The project is expected to bring considerable economic benefits to both countries.

“The cableway can carry 10 tons per hour in each direction. The carrying ropes are 22mm in diameter and have a breaking load of 41.9 metric tons. They are made up of 360-metre lengths connected by coupling sleeves of high-grade steel, the ends being held by cast metal cones so that they cannot be pulled out.

Each of the six interconnected sections has its own traction line, an endless wire rope 14mm in diameter with a breaking load of 10.8 tons. The cars are automatically attached to and detached from it by special grip. There are special cabs for passengers and special carriers for long objects like logs.

The speed of the system is 2.5m per second or 500 feet per minute. The normal distance between cars is 180 metres. When in full operation, a total of some 440 cars are under way and about 60 cars are on the sidings or in storehouses. Loads are automatically weighed before dispatch.

All the stations and supporting towers have steel frameworks. The steepest gradient is about 40 per cent and the longest span is 1,116 metres, measured horizontally. A telephone line parallels the cableway.”

INDEX of Records of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, Entry 46: Intelligence Library, 1932-1947

No. EO-100B, 12 March 1943, railways in Indo-China. Report No. 5-b(2), USSBS Index Section 6

https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/4009619

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2012) and also gives talks on Việt Nam railway history to visiting groups.

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group Rail Thing – Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam for more information about Việt Nam’s railway and tramway history and all the latest news from Vietnam Railways.

You may also be interested in these articles on the railways and tramways of Việt Nam, Cambodia and Laos:

A Relic of the Steam Railway Age in Da Nang

By Tram to Hoi An

Date with the Wrecking Ball – Vietnam Railways Building

Derailing Saigon’s 1966 Monorail Dream

Dong Nai Forestry Tramway

Full Steam Ahead on Cambodia’s Toll Royal Railway

Goodbye to Steam at Thai Nguyen Steel Works

Ha Noi Tramway Network

How Vietnam’s Railways Looked in 1927

Indochina Railways in 1928

“It Seems that One Network is being Stripped to Re-equip Another” – The Controversial CFI Locomotive Exchange of 1935-1936

Phu Ninh Giang-Cam Giang Tramway

Saigon Tramway Network

Saigon’s Rubber Line

The Changing Faces of Sai Gon Railway Station, 1885-1983

The Langbian Cog Railway

The Long Bien Bridge – “A Misshapen but Essential Component of Ha Noi’s Heritage”

The Lost Railway Works of Truong Thi

The Mysterious Khon Island Portage Railway

The Saigon-My Tho Railway Line

The Trans-Asia Railway (TAR) and Singapore-Kunming Rail Link (SKRL) schemes

Tân Ấp junction today.

The old Société Levallois-Perret railway bridge at Khe Ve (formerly Xóm Cục)

The view up river at Khe Ve (formerly Xóm Cục)

Ruins of an old brick railway viaduct

The overgrown bases of old aerial tramway gantries

Another old aerial tramway gantry

A late afternoon freight train speeds northwards past Tân Ấp

This is great, do you have the old plans or new drawing for the thk Vietnam line, we are in Loas, and want to try and work with wood chipping and iron miners like ourselves to get this back into funding stage to open up the region.

Regards

Cameron

Hi Cameron, the National Archives in Hanoi has files with detailed maps of the line but unfortunately I was not allowed to copy these so the simple map in this article is the best I could do. As for the cable car, little has survived and my search was hindered by the nature of the terrain and the fact that this is a border zone with strict security which stretches several kilometres. Incidentally, B R Whyte’s The Railway Atlas of Thailand, Laos and Cambodia (White Lotus Press, 2010) also has a basic map of the entire line to Thakhkek showing all of the projected stations.

Detailed plans of the several colonial Thakek-Tan Ap projects can be viewed and copied at Archives Nationales d’Outre-mer, in Aix-en-Provence, France, including the cablecar project and construction contracts.

In 2009, I saw plans of the more recent Vietnam project at the Thakhek Ministry of Transport office, Laos.

Thanks, must go back to Aix sometime and have another look! Would also be interesting to see the more recent plans. But what I am trying to find is a picture of a train on this line, sadly it seems that none survived.