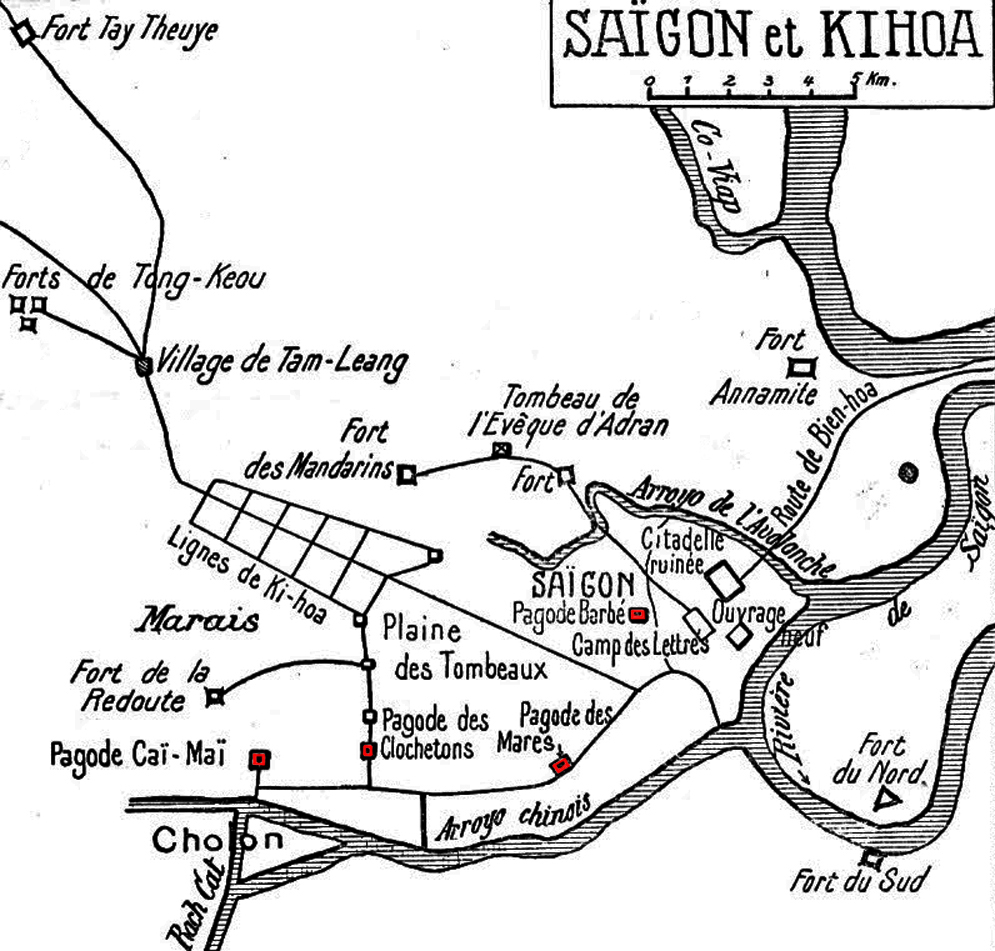

This map shows the location of the line of pagodas in the years 1859-1861

At the start of the French conquest in 1859-1860, colonial forces converted four ancient temples into fortresses with the aim of protecting Saigon and Chợ Lớn from attack by Vietnamese royal troops. All equipped with heavy artillery, these temples became crucial front line fortifications during the seige of Gia Định (1859-1861), but today traces of just one survive.

After capturing Gia Định Citadel and securing control of Chợ Lớn in February 1859, the French and their Spanish allies found themselves under seige by a 32,000-strong Vietnamese army under the command of General Nguyễn Tri Phương (1800-1873), Governor of Gia Định Military District. To guard against attack from Vietnamese troops to the north, they established a 7km east-west defensive line from Sài Gòn to Chợ Lớn.

The capture of Saigon by Frenco-Spanish expeditionary forces, by Antoine Léon Morel-Fatio

Four large fortresses were established along its length, but instead of constructing these fortresses from scratch, the French occupied four ancient temples and rebuilt them as military installations. As a result, the defensive line became known as the ligne des pagodes (line of pagodas).

At the easternmost end of the ligne des pagodes was the Khải Tường Pagoda, known to the French as the pagode de l’Aurore des presages and later as the pagode Barbé, which stood on the site of today’s War Remnants Museum at the junction of modern Võ Văn Tần and Lê Quý Đôn streets (district 1).

Gia Định changed hands several times during the Tây Sơn War, and Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (the future Emperor Gia Long) is known to have taken refuge in this pagoda with his family on several occasions. It was here on 25 May 1791 that his second wife Trần Thị Đang, later Queen Thuận Thiên (1769-1846), gave birth to Nguyễn Phúc Đảm, later Emperor Minh Mạng. In 1804, the Emperor Gia Long presented to the pagoda a Buddha statue – described by historian Vương Hồng Sển as a “gigantic, gold plated masterpiece” – and also installed a stone stele more than two metres high, commemorating his family’s links with the pagoda.

An 1861 image of the pagode Barbé, which once stood on the site of the War Remnants Museum

In 1833, Gia Long’s son and successor Minh Mạng funded a major restoration and granted the pagoda in which he had been born the honorific name Quốc Ân Khải Tường tự (Khải Tường Pagoda, Benefactor of the Nation). Although the giant Buddha image has not survived, a smaller Amitabha Buddha (Phật A Di Đà) presented to the pagoda by the Emperor Gia Long may still be seen today in the Việt Nam History Museum.

On 25 May 1860, French forces occupied the Khải Tường Pagoda and transformed it into a military post under the charge of Captain Nicolas Barbé. However, on 7 December 1860, Barbé was ambushed and beheaded during a devastating attack by General Phương’s Vietnamese troops. Angry French soldiers subsequently destroyed many of the remaining pagoda buildings and buried Captain Barbé in the grounds, erasing the inscription on Gia Long’s royal stele and using it as Barbé’s tombstone. Henceforth, the site became known to the French as the “pagode Barbé” and the street next to it (now Lê Quý Đôn street) as rue Barbé (sometimes spelled Barbet).

For a while after the conquest, the surviving pagode Barbé buildings functioned as the first campus of the École normale, but by the 1870s that institution had been found a permanent home near the Naval Arsenal.

A colonial building which originally housed part of the War Remnants Museum

In the 1880s the old pagode Barbé was demolished, permitting the site to be redeveloped. By the mid 20th century it belonged to nationalist politician Bùi Quang Chiêu, who had a colonial-style villa built here.

Chiêu’s daughter, Dr Henriette Bùi, later established an obstetrics and gynaecology clinic on the site, and in 1947 this became the Medical and Pharmaceutical Faculty of Saigon University. When the Faculty relocated elsewhere in the mid 1960s, the compound found its way into American hands and eventually became the US-ARV Office of Civilian Personnel and USAID Mission Warden’s Office (though it never served as a USIS Office as commonly suggested by tourist literature). A war museum was established here on 4 September 1975 and this has since been rebuilt on several occasions.

The second fortress in the ligne des pagodes was located in the area bounded by modern Phạm Viết Chánh, Cống Quỳnh, Nguyễn Trãi and Nguyễn Văn Cừ streets (district 1). According to Trịnh Hoài Đức’s Gia Định thành thông chí (early 19th century), it was originally known as the Hiển Trung tự (Temple of Brilliant Loyalty) or the Miếu Công thần (Temple of Meritorious Officials) and was constructed in 1795 on the site of an earlier Khmer sanctuary by Lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh to honour the cult of 1,015 heroic royal mandarins. After being taken over by the French, the complex was turned into a military installation known as the pagode des Mares (Pagoda of the ponds), apparently because it incorporated two large ponds.

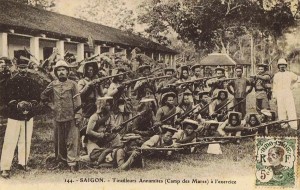

“Annamese riflemen” training at the camp des Mares

In 1875, part of the pagode des Mares compound became an experimental farm (the Ferme expérimentale des Mares) belonging to the Jardin botanique et zoologique de Saïgon, and was used to grow new varieties of coffee, mango, pandanus, jute, indigo and sugar cane (see Jean-Baptiste Louis-Pierre, father of Saigon’s greenbelt).

By the turn of the century, the fortress-temple itself had been rebuilt as the Camp des mares, a large military barracks occupied by “troupes indigènes” (local troops) of the “Régiment Annamite.”

After the departure of the French in 1954, part of the compound was completely redeveloped, while the Camp des Mares barracks was extended southwards into neighbouring land and transformed into the RVN’s Directorate General of National Police, today the southern branch headquarters of the Ministry of Police.

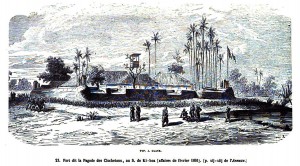

Little is known about the early history of the third ligne des pagodes fortress, the Kiểng Phước Pagoda, which was known to the French as the Pagode des Clochetons. Believed to have stood on the site of today’s Hùng Vương Hospital, at the junction of modern Hồng Bàng and Lý Thường Kiệt streets in Chợ Lớn (district 5), it was occupied in early 1860 and became the site of several fierce battles as the French sought to extend their control over the northern perimeter of that city.

The pagode des Clochetons in 1861

Like the pagode Barbé, the Pagode des Clochetons was abandoned soon after the conquest and the site was then completely redeveloped. However, modern Phù Đổng Thiên Vương street, which once led south from the pagoda, was known right down until 1955 as rue des Clochetons.

Perhaps the most famous fortification in the ligne des pagodes was the Mai Sơn tự or Cây Mai Pagoda (Plum Tree Pagoda), known to the French as the pagode Cai-Mai or the pagode des Pruniers. It was originally a Khmer pagoda, and it got its name from the fine white-blossomed plum trees which grew in its grounds. Restored in 1816, the Cây Mai Pagoda was known in the pre-colonial era as a centre of artistic creativity frequented by leading southern poets such as Phan Văn Trị, Bùi Hữu Nghĩa, Nguyễn Thông, Trần Thiện Chánh, Tôn Thọ Tường, Hồ Huân Nghiệp and Trương Hảo Hiệp. By this period too, the name Cây Mai was also being used to describe the fine blue-glazed ceramics produced by several nearby Minh Hương kilns.

Occupied by the French on 23 April 1859, the Cây Mai Pagoda was perhaps the most important of all of the fortresses in the lignes des pagodes because of its strategic location on the northwest outskirts of Chợ Lớn, centre of the rice trade and chief source of supplies for the Franco-Spanish expeditionary force. Uniquely amongst the four tenple-fortresses, it was located on a waterway, which made it possible to supply its garrison by boat via the Bến Nghé and Lò Gốm creeks. In the mid 1860s, the Chợ Lớn street known today as Tản Đà was christened avenue Jaccaréo, after the gunboat Jaccaréo which was tasked with keeping the Cây Mai Pagoda garrison supplied in the period 1859-1861.

A small shrine is still maintained on the site of the original Cây Mai Pagoda sanctuary

In 1872 the remaining Cây Mai Pagoda buildings were destroyed and the compound was rebuilt as a military barracks, a function which it has retained ever since. However, in 1909 a Buddhist monk took cuttings from the ancient plum trees in the barracks compound and transplanted them in the grounds of the nearby Phụng Sơn Pagoda, where they thrive to this day.

In 1940 the Cây Mai barracks complex was used briefly as a detention centre and in the 1960s it became a training school for intelligence officers. Today it is a People’s Army barracks and is thus off limits to visitors. However, a small shrine is still maintained on the site of the original sanctuary.

The lignes des pagodes played an important role in the French war of conquest, enabling the French to retain control of the two ports of Saigon and Chợ Lớn, despite the threat from overwhelmingly superior royal forces to the north. The military stalemate continued until October 1860, when the arrival of massive reinforcements from the French expeditionary corps in China made it possible for the French to break the seige of Gia Định by capturing the Lignes de Ky-Hoa (Chí Hòa). Within months of that key battle, the French were able to extend their control over most of the six provinces of Cochinchina.

The Cây Mai Pagoda barracks in 1895 (above) and a google map (below) showing the same location today

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.