White’s vessel the USS Franklin, pictured rounding Portovenere near La Spezia in about 1819

On 7 October 1819, Lieutenant John White (1782-1840), a member of the East India Marine Society of Salem, Massachusetts, arrived in Saigon in the US Navy brig Franklin. His account of his visit, published in A Voyage to Cochinchina by John White, Lieutenant in the United States Navy (Boston, 1823), has been described by Robert Hopkins Miller (The United States and Vietnam, 1787-1941. National Defense University Press, 1990) as “a vivid example of an early American reaction to the Vietnamese and their ways.” This is the first of two excerpts from the book describing his experiences in the Saigon of King Gia Long’s reign.

To read part 2 of this serialisation click here

On 9 October at 9am, we embarked in our boats and proceeded across the river through a fleet of several hundred of the country craft which were lying before the city; during which time, our noses were saluted with the perfumes of fish-pickle and other agréeables proceeding from them. Our eyes were amused by the crowds of natives in different vessels lining the bank of the river, who flocked to see the don-ong-olan or olan-ben-tai, strangers from the west or white strangers; while our ears were greatly annoyed by the constant and vociferous bursts of admiration which our appearance excited.

The right bank of the Saigon river

Our party consisted of the commanders of both vessels, with the two young gentlemen, Messrs Putnam and Bessel, a sailor of the Marmion, who spoke the Portuguese language well, old Joachim, the Portuguese pilot, a commissary of the marine, and four other mandarins; the whole proceeded by three of the government linguists, bearing the presents.

We landed at a great bazaar or market place, well supplied with fruits and various other commodities, exposed for sale by women scattered about without order or regularity, each one the focus of her own little domain. Some of these locations were covered with screens of matting, erected on bamboos, to protect the occupants and their wares from the burning sun.

From thence, our route lay through a spacious and regular street, lined with houses of various descriptions, some of which were of wood, covered with tiles, and tolerably decent; others were of the most humble description, and none of them exceeded the height of one storey. A few had enclosed courts in front, but they were generally placed close to the street.

Toiling under a scorching sun, through a street strewn with every species of filth; beset by thousands of yelping mangy curs; stunned alike by them and the vociferations of an immense concourse of wandering natives, whose rude curiosity in touching and feeling every part of our dress, and feeling our hands and faces, we were frequently obliged to chastise with our canes (which, however, made no impression of fear on the survivors); and the various indefinable odours, which were in constant circulation; these were among the amenities which were presented to us on this, our first excursion into the city.

A Saigon market scene, from the journal “Tour du Monde” by French naturalist Dr Morice (1872)

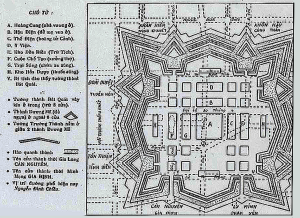

At the end of the first street, however, the scene changed into one of a more pleasing nature. Our route lay through a serpentine covered way, walled with brick and cut nearly a quarter of a mile through a gentle acclivity, covered with verdure, on our arrival at which, the native canaille, biped and quadruped, left us, and we soon arrived, by a handsome bridge of stone and earth, thrown over a deep and broad moat, to the great south gate of the [1790 Gia Định] Citadel [the Càn Nguyên Gate, located in the vicinity of the modern Đồng Khởi-Lý Tụ Trọng street junction], or more properly, perhaps, the military city; for its walls, which are of brick and earth, about 20 feet high and of immense thickness, enclose a level quadrilateral area of nearly three quarters of a mile in extent on each side.

Here, the Viceroy and all military officers reside, and there are spacious and commodious barracks, sufficient to quarter 50,000 troops. The regal palace stands in the centre of the city, on a beautiful green, and is, with its grounds of about 8 acres, enclosed by a high paling. It is an oblong building of about 100 feet by 60 feet, constructed principally of brick, with verandas enclosed with screens of matting; it stands about 6 feet from the ground, on a foundation of brick, and is accessible by a flight of massy wooden steps.

On each side, in front of the palace, and about 100 feet from it, is a square watch tower of about 30 feet high, containing a large bell. To the rear of the palace, at a distance of about 150 feet, is another erection of nearly the same magnitude, containing the apartments of the women, and domestic offices of various kinds; the roofs covered with glazed tiles and ornamented with dragons and other monsters, as in China. This establishment is devoted to the use of the king and royal family, who have never visited Saigon since the civil wars; it has, consequently, during that period, not been occupied. It is, however, used as a place of deposit for the provincial archives and the royal seal; and all important business requiring this appendage is here consummated. On passing these buildings, we were directed by the attendant mandarins, who set the example, to lower our umbrellas by way of salute to the vacant habitation of the “Son of Heaven.”

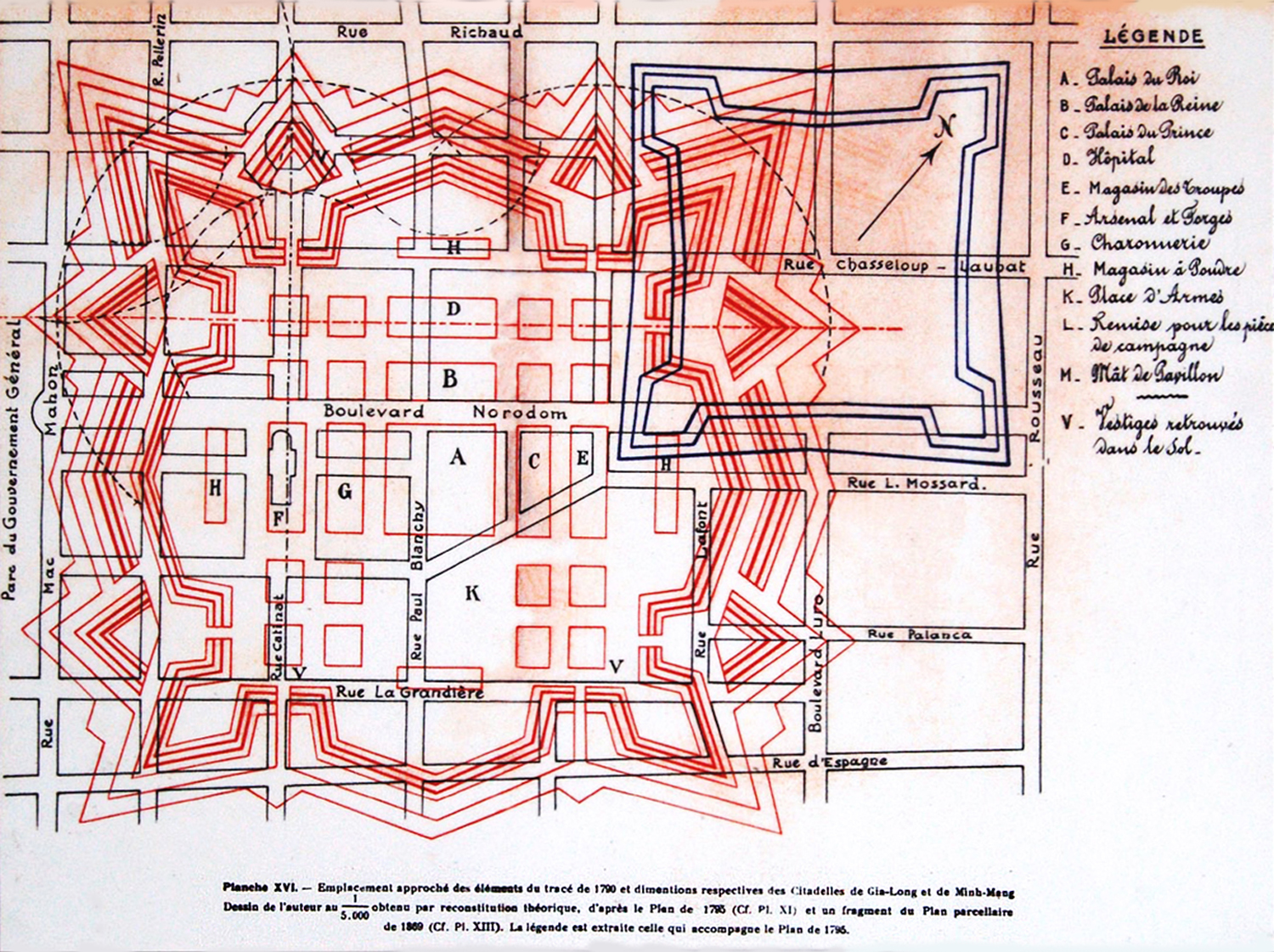

A map of the 1790 Gia Định Citadel, drawn in the early 19th century, collected by Petrus Ky and annotated by Nguyễn Đình Đầu

We shortly arrived before the palace of the governor and were shown into a guard-house opposite, where we were told we must remain till our arrival should be announced; for which purpose, a mandarin and a linguist were dispatched. We had not been long waiting when we were informed that the great personage within was ready to receive us.

We entered the enclosure by a gateway in the high paling surrounding the governor’s residence; in front of which, at a distance of 10 feet, was a small oblong building parallel with the gateway, and apparently placed there as a mark. After we had passed this erection, we found ourselves in a spacious court, and directly in front of us, at about 150 feet from the entrance, was the governor’s house, a large quadrilateral building, 80 feet square and covered with tiles. From the eaves in front continued a gently sloping roof of tiles, to the distance of 60 feet, supported by round pillars of rosewood, beautifully polished. The sides of this area were hung with screens of bamboo. At right angles with the main building were placed (three on each side of the centre) platforms, raised about 1 foot from the floor, which was of hard, smooth earth. These platforms were each about 45 feet long and 4 feet wide, constructed of two planks, 5 inches thick, nicely joined together and highly polished. Between these two ranges of platforms, at the farther end of the area, was another platform, raised 3 feet from the floor, composed of a single plank, 6 feet by 10 feet square, and about 10 inches thick, resembling boxwood in colour and texture, and from almost constant attrition, reflecting adjacent objects with nearly the fidelity of a mirror.

On this elevation was seated, in the Asiatic style, cross-legged, and stroking his thin white beard, the acting governor; a meagre, wrinkled, cautious-looking old man, whose countenance, though relenting into a dubious smile, indicated anything but fair dealing and sincerity. On the platforms on each side of the throne were seated mandarins and officials, their different degrees of rank indicated by their proximity to the august representative of the sovereign, We doffed our beavers and made three respectful bows in the European style, which salutation was returned by the governor by a slow and profound inclination of the head. After which, he directed the linguists to escort us to a bamboo settee on his right hand, in a range with which were also some chairs of apparently Chinese fabric, which the linguists told us had been placed there expressly for our accommodation.

A Nguyễn dynasty mandarin

A motion of the governor’s hand indicated a desire that we should be seated, with which we complied. The linguists then proceeded to the foot of the throne with the presents, which they held over their heads, in a kneeling posture, while the different articles were passed to him by several attendants in waiting. After attentively viewing each article separately, with marks of evident pleasure, he expressed great satisfaction and welcomed us in a very gracious manner, making many enquiries about our health, the length of our voyage, the distance of our country from Annam, the object of our visit, etc. After we had satisfied him in these particulars, he promised us every facility in the prosecution of our views. Tea, sweetmeats, areca and betel were passed to us, and we vainly attempted to introduce the subject of sagouètes (presents) and port charges for anchorage, tonnage, etc (the rate of which we wished to have established), all recurrence to these subjects being artfully waived by him for the present; and he promising to satisfy us at the next interview, we took our leave and, as it was still early in the day, we proceeded to gratify our curiosity by taking a walk through the city.

On our return towards the great southern gate by which we had entered, we passed a large bungalow (a light airy building constructed generally of bamboo and roofed with thatch), under which were arranged about 250 pieces of cannon, of various calibres and fashions, many of them brass, and principally of European manufacture, generally mounted on ship-carriages in different stages of decay. Among them, we noticed a train of about a dozen pieces of field artillery, each marked with three fleurs de lys and bearing an inscription importing that they had been cast in the reign of Louis XIV, in tolerable preservation. Near this place was a sham battery of wooden guns for exercise; and at the main guard, near the gate, were several soldiers undergoing the punishment of the cangue, [a kind of pillory used for public humiliation and corporal punishment] and on this occasion we understood that the cangues of the military were made of bamboo, while those used for other offenders were of a species of heavy black wood.

On the north side of the eastern gate was a bastion with a flagstaff, where the Annamese colours are displayed on the first day of the new moon and on other occasions.

A mandarin’s tomb

The main gates, of which there are four, are very strong and studded with iron in the European style; and the bridges thrown across the moat are decorated with various military and religious bas reliefs on panels of masons’ work. Over the gates are square buildings with tiled roofs and a stairway leading to the top of the ramparts, on each side of the gate, inside the wall.

In the western quarter of the area within the walls is a cemetery containing several barbarously splendid mausoleums of mandarins in the Chinese style. Some of them bear inscriptions and effigies on stone, of very tolerable sculpture.

In the north-eastern section are six immense buildings, enclosed with palings, separate from each other. They are each about 120 feet long by 80 feet wide. The roofs, composed of rafters of great strength and covered with glazed tiles, are supported by abutting columns of brick, the intervals being filled with massy woodwork. The walls are about 18 feet high. These are the magazines of naval and military stores, provisions, arms etc.

Many small groups of soldiers’ huts were scattered about within the walls, situated in a picturesque manner among the foliage of various tropical plants. Among others, we noticed several clumps of the castor bean.

Many pleasant walks are laid out in various directions, planned on each side, with the palmaria, a beautiful plant resembling a pear tree, bearing a profusion of white odiferous flowers, which in October and November impregnate the air to a great distance with their perfume. From these flowers, the natives extract an oil which is considered by them a panacea for all kinds of wounds.

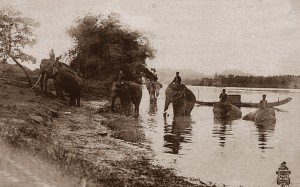

Drivers with their elephants in the river

On the declivity outside the gate, through which the tortuous covered way is cut, several of the royal elephants were grazing, attended by their drivers, who were sitting on their necks. Some of these beasts were of immense size, indeed, much larger than any I had ever seen in any part of India. The drivers, or rather attendants, of these huge animals, are provided with a small tube of wood, closed at each end, equidistant from which is a round lateral aperture, into which they blow, producing a noise similar to blowing into the bung-hole of an empty cask, for the purpose of warning passengers, or others, of their approach, for they seldom give themselves the trouble to turn aside for any small impediment in their path; and it was amusing to see the old women and others in the bazaars, on hearing the approach of an elephant horn, gather up their wares, and retreat, muttering, to a respectful distance, while the animal was passing to and from the riverside where they resorted to drink. On passing us they would slacken their pace and view, with apparent interest, objects so unusual as our white faces and European garb presented; nor were we totally divested of some degree of apprehension at first, from the intense gaze and marked attention of these enormous beasts. Indeed, the Annamese appeared to fear that some accident might accrue to us from our novel appearance, and advised us to assume the costume of the country, to prevent any accident; which advice we generally hereafter complied with, at which they were always highly gratified, viewing it as a compliment. Nor was this unattended with other advantages, for our dresses were those of civil mandarins of the second order, which gained us greater respect from the populace. The dress worn by me is now in the museum of the “East India Marine Society” of Salem.

Another Saigon market scene

We passed through several bazaars, well stocked with fresh pork, poultry, fresh and salt water fish, and a great variety of fine tropical fruits. Vegetables, some of which had never before been esteemed as edible, were exposed for sale. The Annamese, like the French, eat many legumes and herbs which we generally reject.

Our attention was excited by the vociferations of an old woman, who filled the bazaar with her complaints. A soldier was standing near her, loaded with fruits, vegetables and poultry, listening to her with great nonchalance. She finally ceased from exhaustion, when the soldier, laughing heartily, left the stall and proceeded to another, where he began to select what best suited him, adding to his former store. We observed that in the direction he was moving, the proprietors of the stalls were engaged in secreting their best commodities.

On enquiry, we found that the depredator was authorised, without fear of appeal, to cater for his master, a mandarin of high rank, and his exactions were levied at his own discretion, and without any remuneration being given. This, we afterwards found, was a common and universal practice. There was, however, great partiality observed in the exactions; for we had frequent opportunity to notice that poor old women were the victims of their extortion, while young girls were passed by with a smile or salutation.

As a proof of the abundance which reigns in the bazaars, and the extreme cheapness of living in Saigon, I shall quote the prices of several articles: viz, pork: 3 cents per pound; beef: 4 cents per pound; fowls: 50 cents per dozen; ducks: 10 cents each; eggs: 50 cents per hundred; pigeons: 30 cents per dozen; varieties of shell and scale fish, sufficient for the ship’s company: 50 cents; a fine deer: 1 dollar 25 cents; 100 large yams: 30 cents; rice: 1 dollar per picul of 150 pounds English; sweet potatoes: 45 cents per picul; oranges: from 30 cents to 1 dollar per hundred; plantains: 2 cents per bunch; pamplemousses or shaddocks: 50 cents per hundred; coconuts: 1 dollar per hundred; lemons: 50 cents per hundred.

The Saigon river

During our walk, we were constantly annoyed by hundreds of yelping curs, whose din was intolerable. In the bazaars, we were beset with beggars, many of them the most miserable, disgusting objects, some of whom were disfigured with leprosy and others with their toes, feet and even legs eaten off by vermin and disease. Nor were these the only subjects of annoyance; for notwithstanding the efforts and expostulations of the officers who accompanied us, and our frequently chastising them with our canes, the populace would crowd round us, almost suffocate us with the fetor of their bodies, and feel every article of our dress with their paws. They even proceeded to take off our hats and thrust their hands into our bosoms; so that we were glad to escape to our boats and return on board, looking like chimney sweeps, in consequence of the rough handling we had received.

This late 19th century map shows the location of the 1790 and 1835 citadels in relation to the colonial street plan of Saigon

To read part 2 of this serialisation click here

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.