Sampans moored near the quai des Messageries maritimes

In 1881, wealthy Parisian photographer Hugues Krafft (1853–1935), his brother Edouard Hermann and his two friends Louis Borchard and Charles Kessler, embarked upon a world tour modelled on that of Phileas Fogg in Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days. This translated excerpt from Krafft’s 1885 book Souvenirs de notre tour du monde (Memories of our World Tour) describes their 48-hour stopover in Saigon in August 1882, during a five-month trip which took in India, Ceylon, Java, China and Japan.

An 1892 painting of Hugues Krafft by Léon Bonnat

After two days at sea, the Djemnah arrived in Cochinchina. As it’s easy to see from the map, Saigon is located some distance from the coast, and reaching it involves around three hours’ navigation from Cap Saint-Jacques. This is where the telegraph cable passes to facilitate communication with China, and where a pilot comes on board ships to guide them up the Saigon River.

Once we’d entered the river – a yellow-coloured arm of the great Mekong, the “Nile” of Cochinchina – we quickly lost sight of the promontory of Cap Saint-Jacques, and soon we could see nothing but submerged brush and endless rice fields. As we progressed, the river began to turn in zigzags like the Seine near Paris, so that as we approached Saigon we could see, sometimes to the right and sometimes to the left, the square towers of the cathedral, which seemed to be the only high point in the midst of a uniform plain.

Arriving in Saigon harbour, which had a quiet aspect, we were transferred ashore by sampan, a type of native canoe rowed by Annamite boatmen. These first members of the Annamite race that we encountered did not charm us.

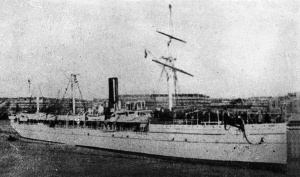

The Djemnah, built 1874 and weighing 3785 tons

They were nervous little men with bad expressions, garbling a few French phrases in a rude and guttural way and revealing teeth blackened by betel. Their attire, and especially their hairstyle, was far from picturesque. The latter consisted of a red or green handkerchief, carelessly knotted around a small bun and hung like a rag over their ears and necks.

“Oh what a pretty harbour! What beautiful trees! Victoria carriages! Houses with balconies! A café!” we cried as soon as we set foot on the quayside. One might easily have mistaken this place for Chatou, for it would surely have been impossible to find anywhere else so far from home and yet so reminiscent of France.

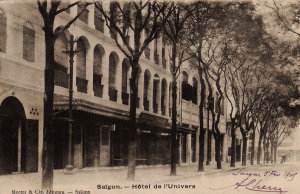

We took rooms at the Hôtel de l’Univers, a two-storey building located in the first street which intersects at right angles with that great Saigon artery, the rue Catinat.

The Hotel de l’Univers, pictured in 1906

This hotel, which had its name written on a blue sign with white letters, had been recommended to us for its cuisine, the reputation of which was maintained by M Olivier, former head chef of the Governor.

The best thing about the Hôtel de l’Univers was indeed the cuisine. Everything else about this place brought to mind a small provincial hotel; the walls of the rooms were hung with drab wallpaper and decorated with coloured lithographs representing the Bal Mabille or the sentimental allegories of Louis-Philippe.

If the comfort of the rooms was higher than that of the Indian hostels we had stayed in, the hotel’s hydrotherapy annex left a great deal to be desired. These facilities were as primitive as they were unkempt, and their Chinese staff were also in urgent need of some retraining. These boys with pigtails were very sullen and unpleasant individuals, who most of the time couldn’t even be bothered to respond to the requests of the guests.

Calling a malabar in colonial Saigon

Taking advantage of the obliging offer of two of our fellow travellers from the Djemnah, we went with them early next morning to Chợ Lớn, a very important city located just a few kilometres from Saigon.

This is the major rice market of the country, and the Chinese, who are very numerous there, control all of its trade. The ponies pulling our Victoria carriage ran like the wind, but in a very ugly way which seemed typical of their species.

The dusty soil was of a pronounced red brick colour, which lent a strange hue to the shrubs and hedges lining our route. A large plain known as the Plaine des tombeaux (Plain of Tombs) lay to the right of the road, alongside which ran the new steam tramway connecting Saigon with Chợ Lớn.

The grand Chợ Lớn residence of Đỗ Hữu Phương

The main purpose of our trip was a visit to a well-known Annamite personage, Đỗ Hữu Phương, the local prefect and Deputy President of the Chợ Lớn Municipal Council. Given that it was still quite early in the morning (7am!), we were not surprised when M Phương received us in his dressing gown.

He was quite the Annamite type. Very proud to have been in Paris, he jabbered a little in French, but as he stuttered badly, we found him very hard to understand. However, he was on very good terms with one of our companions and seemed delighted to receive us. He showed us the many objects in his famous antique collection, including ancient weapons, porcelain and Chinese and Tonkinese furniture, as well as articles specially reserved for the worship of his own ancestors, including an ornate shrine adorned with calligraphic works and incense burners.

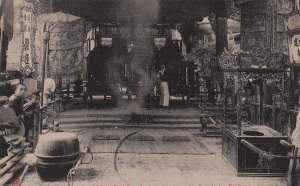

The interior of a Chinese Assembly Hall in Chợ Lớn

We were offered cognac, vermouth and… Caporal tobacco! Clear proof that in M Phương’s house, some French habits prevailed over those of his own country. We also met his wife and several of his nine children, who gathered timidly in the doorway to observe us! Madame Phương presented everyone in our group with bouquets of small yellow flowers, a gesture accompanied by a frightening smile which revealed her betel-blackened mouth.

M Phương showed us his garden, in which, following the widespread taste in the East, he raised all sorts of animals, including birds, deer and crocodiles. Then he took us to one of the main Chinese pagodas in Chợ Lớn. This was a large and luxurious temple, fairly new and decorated at all corners with brightly-coloured ceramic sculptures, porcelain decorations and grimacing statues.

A late 19th century Saigon street scene

Returning to Saigon, we had lunch and then followed the example of all Saïgonnais by taking a nap until 2pm. At that hour, the city’s shops and offices, closed since 11am, reopened. In the late afternoon, as the heat began to abate, the city streets slowly regained their animation.

Making the most of the little time remaining, this traveller quickly inspected the local sights: the Cathedral, a beautiful monument of brick and stone; the Palace of the Governor, a large and brand new edifice, doubtless imposing in the imaginations of local people, but in our view looking rather too much like a casino; the Botanical and Zoological Gardens; the Water Tower; and the Citadel with its Marine Infantry Barracks. The latter, very airy with iron verandahs on every floor, had been very well built.

Colonial military personnel in Saigon

But we saw very few of our soldiers there. I should mention that, despite the tropical heat, they are required to wear a collared shirt, a black tie and a jacket, all made from material thick enough for the icy slopes of the Himalayas! We must sympathise with those among their number who must stand guard wearing this uniform, and ask why we cannot learn from the practices of the British military in India and Ceylon, instead of allowing such errors to continue?

How shall I sum up Saigon? This city – perfectly clean, with streets which intersect tidily at right angles, are equipped with sidewalks, manholes, hydrants and lined with symmetrically-planted trees – seems better administered than any city we’ve seen so far on our trip. However, I would add that, in the light of the city’s precarious state just 20 years ago, the recent improvements tend to make us forget the misconduct in failing to establish the capital at Cap Saint-Jacques.

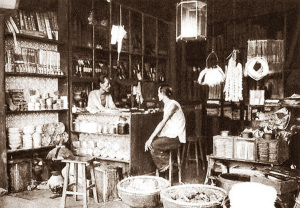

A Chinese store in colonial Saigon

The 1,300-strong population comprises French, Malay, Tamil, and above all the active and industrious Chinese, who account for most of its small businesses and industries. It is from their ranks that the city’s tailors, launderers, carpenters and shoemakers are drawn, centralising in the hands of one race all the trades necessary for the needs of the Europeans and even the native Annamites.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.