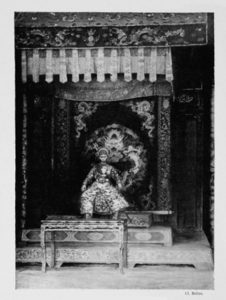

“Annam – Hue – Tribunes et cavalier du roi, vue des jardins”

Packed with the usual colonial arrogance and assumptions of western superiority, this short 1912 article by Henri Cosnier sheds interesting light on French Governor General Paul Doumer’s policy towards the royal court in Huế

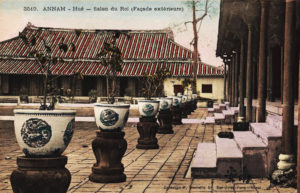

The powerful breath of modernism carries off, one after the other, the sumptuous traditions of the court of Hue.

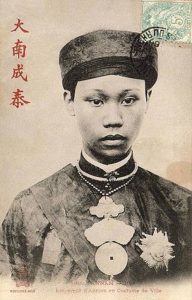

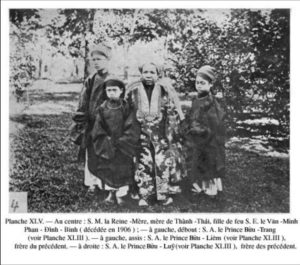

Emperor Thành Thái in 1898 (Le Monde illustré, 11 December 1898)

The republican simplicity of the representatives of France accredited to that city seems to have affected the sovereigns of Annam and their entourage. The era of melon hats and varnished court shoes is finally at an end, for the greater good of the princes and mandarins, whose manners and dress tend to simplify ever more each day.

Where are the splendour and the regalia with which the Asiatic monarchs once surrounded themselves when they left their palaces to mingle with the flood of the populution? All ancient rites have long since disappeared; western civilisation has chased before it that grandiose spectacle which once accompanied even the smallest walks by Gia-Long, Minh-Mang and Tu-Duc. The present sovereign of Annam [Duy Tân], whom we raised in an atmosphere of extreme civilisation, is still too young to indulge in modernism, but his predecessor, the sinister Thanh-Thai, often ventured out alone into his capital, on foot or on horseback, on a bicycle or in an automobile, just like a mere mortal.

He was the first to modernise, to cut his hair short, to dine at the Résidence Supérieure, and to do the American square dance in the salons of the Cercle de Hué.

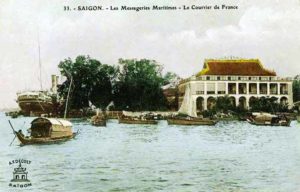

He also began to travel, visiting Cochinchina and Saigon several times, where, incidentally, he gave the chiefs of protocol something of a headache.

“The cyclist emperor of Annam,” from L’Empereur d’Annam en Cochinchine, L’Illustration, 22 January 1898

He then came to Tonkin to inaugurate the railway line from Hanoi to Haiphong, the Doumer Bridge and the Grand Palais de l’Exposition.

He attended military parades, the Philharmonic, parties at the Palais du Gouvernement général, and, as a mere mortal forgetting his divine origin, made innumerable yet futile purchases in our houses of commerce.

He also revelled in royal gallantry, earnestly asking the officers attached to his person if, for a great deal of money, he could not be permitted a tête-à-tête with one of our female compatriots!

In a word, he did just as Alfonso XIII or Edward VII had done when travelling to Paris: he modernised himself.

I dare not affirm that, in the eyes of his people and of the old mandarin guardians of millennial rites and historical traditions, he had plumbed new depths.

It is a certain fact that he lost the greater part of his prestige. And I have heard that the first trip which he made with M. Doumer had no other aim.

Paul Doumer, Governor General of Indochina from 1897 to 1902

The former governor wished to show him to his people, and at the same time to destroy the legend which represented the Emperor of Annam as a superman, a demi-god living in the mysteries and prodigies of a palace populated by spirits, inaccessible even to the gaze, and in constant relations with the divinity.

The popular imagination, so thirsty for marvels, had imagined him in a fairy-like setting, walking on clouds, as beautiful as the divinity itself, wise as a Buddha, on familiar terms with the immortals whose images are seen in the dim light and sandalwood smoke of pagodas.

The visit of H M Thanh-Thai to Hanoi was a disenchantment. The crowd, massed for his arrival on the banks of the Red River, was astonished and disappointed to see a small boat laden with tricolour flags appear, instead of a royal barge with a hundred oarsmen decorated with heavy banners featuring flaming dragons on yellow brocade.

Was that it? That was all? A vulgar gunboat, like the ones which carried our own chiefs of service. He was dressed in national costume, like a simple scholar or a modest interpreter, comprising a long “cai-ao” of black silk that did not fit the grand cordon de la Légion d’honneur, his head crowned with a turban of black grenadine and his feet shod in the French style.

Emperor Thành Thái and Governor General Paul Doumer inaugurate the Doumer (now Long Biên) Bridge on 28 February 1902

Thus did the great emperor of the East step ashore beside Monsieur Doumer, his eyes roaming somewhat astray, astonished to find himself before this crowd.

He climbed into the Governor’s carriage, sat down opposite a general wearing a white feathered hat, and that was all.

The effect was instantaneous: The ancient prestige of the emperors of Hue had sunk in the eyes of their people.

Annamite plebeians repeated, skeptically: “So this is the Emperor!” They understood that henceforth, the absolute sovereign of the land of their ancestors was indeed the French Republic, and at the moment when the Emperor crossed the threshold of the Pagode des Pinceaux on the Little Lake [Hoàn Kiếm Lake], a coolie threw a stone into his face.

Henri Cosnier

Deputy for the département de l’Indre

Emperor Thành Thái and Governor General Paul Doumer pictured in Hà Nội in February 1902

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.