The Cần Chánh Palace

Kien-Phuc, nephew of Tu-Duc – The assassination of his predecessor – A palace revolution – Causes of our Expedition – The role of M. de Champeaux – The poisoning of Hiep-Hoa

We know by dispatch of the death of the king of Annam, Kien-Phuc, who was aged just seventeen. Who was this sovereign? How had he ascended the throne? In the hands of which party, which mandarins, did he meet his fate? Specific information allows us to give precise details on these various important points.

The Succession of Tu-Duc

Kien-Phuc was the nephew of King Tu-Duc and his fourth adopted son. It is known that Tu-Duc had no children; he had successively adopted four of his nephews: 1. Duc-Duc; 2. Hiep-Hoa; 3. Me-Trui; and 4. Me-Men. The latter, according to Annamite law, had regularly been called to serve the old sovereign, and at length succeeded him under the name of Kien-Phuc.

Tôn Thất Thuyết (1839-1913)

But before he ascended the throne, events occurred which are interesting to relate, and which perhaps throw significant light on his premature death.

Intrigues of the Court

On the death of Tu-Duc, several parties disputed the royal inheritance, in spite of the rules of the Annamite monarchy. That of the first adopted son was at first the strongest, and Duc-Duc was proclaimed sovereign. But his reign was ephemeral; an intrigue by the Minister of War, Ton-That-Thuyet, deposed him within two months. The powerful controller of the royal palace then raised to the throne his creature, Hiep-Hoa, the second adopted son of Tu-Duc.

Ton-That-Thuyet was a relentless but not very intelligent opponent of French influence. His hostility was so open that M. Harmand, then our Commissaire-général in Tonkin, obtained from the French government authorisation to direct an expedition against Hue. The forts at Thuan-An were bombarded and occupied. M. Harmand then imposed on Hiep-Hoa and his ministers a treaty, the clauses of which were unfortunately insufficient, but which stipulated that a garrison of 600 men should occupy the forts on the river some fifteen miles from the capital, and that a guard of 200 men would be attached to our Legation in Hue itself.

The Overthrow of Hiep-Hoa

Unhappy with this adventure, the king resolved to be rid of his protector, Ton-That-Thuyet. But this was a wrong move, since the dismissed minister immediately forged an alliance with the mandarin Nguyen-Van-Tuong, one of our principal opponents who had been well known to us since our first expedition to Tonkin, where he had given much trouble to M. Philastre, the successor to Francis Garnier.

Minister Nguyen-Van-Tuong

Nguyễn Văn Tường (1824–1886)

This person, a former intimate and favourite advisor to Tu-Duc, had married his daughter to a brother of Prince Memen, the last of the four adoptive sons of the former sovereign. He was Minister of Finance, and through his perpetual intrigues had contributed in no small way to provoking our second expedition to Tonkin. Also, he knew very well that, in case our influence should triumph at Hue, all power was at stake for him. This circumstance united the two ministers, who had hitherto been rivals. Ton-That-Tuyet consented to favour the candidature of Prince Memen, dear to Nguyen-Van-Tuong. The two ministers said that it was a matter of life or death for them to have in their devotion a sovereign of their choice, under whose protection they would reign. Prince Memen was their creation; He was only sixteen. But how would they substitute him for Hiep-Hoa in the presence of his protector, the Resident of France?

The Conspiracy of the Two Ministers

Our resident, M. de Champeaux, an old “Cochinchinois” who was well informed about all these intrigues, informed the authorities in Tonkin and asked them for instructions. But they were seemingly so completely absorbed by the events at Song-Koï that they failed to reply to M. de Champeaux’s letters and gave him no order. He could not act on his own initiative because the ministry had ordered him to do nothing without having first referred matters to the Commissaire général of Tonkin, a very long process which usually required about a month. In this way, our Resident was completely paralysed.

In the circumstances, the two mandarins, our enemies, understood that they had the upper hand. They initially planned a coup towards the middle of December, but the king felt so threatened that he moved to be rid of the conspirators, announcing his first public audience to our Resident and forcing them to bring their plans forward. The news of this unusual event, a complete departure from established practice, caused great annoyance in the mandarinate.

Emperor Hiệp Hòa (30 July-29 November 1883)

Yet the two chiefs of the conspiracy realised that this was the opportunity they had been waiting for. They had the audience postponed until the following day, when they knew that M. de Champeaux would be leaving for Thuan-An to ask the commanding officer of our troops to send reinforcements to Hue.

The Poisoning of Hiep-Hoa

The conspirators made Hiep-Hoa swallow poison. The coup d’etat took place very quickly and without any great deployment of forces; only a few soldiers were sent to stand guard around the Missions, in order to prevent them from informing the Residence. As a result, M. de Champeaux did not hear what had happened at Thuan-An until about noon. He then hastened to return to Hue together with fifty soldiers, whom he had obtained with some difficulty. By the time he arrived, at ten o’clock in the evening, everything had calmed down.

The next day the mandarin-interpreter, Father Tho (a former banned Annamite priest) carried to the resident an apocryphal letter of abdication by Hiep-Hoa, saying that the sovereign had committed suicide.

This did not fool M. de Champeaux; without order, he refused to recognise the new king and broke off official relations with the court.

Nguyen-Van-Tuong and Ton-That-Thuyet, who had proclaimed themselves Regents, were thrown into disarray and thought themselves lost when 50 Annamite riflemen from Cochinchina and the gunboat Javeline arrived in Hue. They expected an imminent attack from us and hastily massed five or six thousand men around the residence, pointing all available cannon on their ramparts toward us.

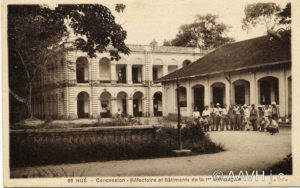

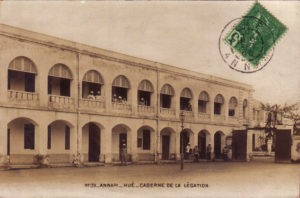

A barracks building in the French Legation

The Legation had a garrison of 150 soldiers. While it had little to fear from the Annamese bands, armed for the most part with pointed bamboos, it was quite exposed, being situated only 700 meters from the Citadel. It could still be bombarded by the cannon on the ramparts. The situation continued to be critical for several days.

Meanwhile, Nguyen-Van-Tuong and Ton-That-Thuyet repeatedly disavowed the bands which they themselves had excited. They protested their friendly intentions and promised to recognise the Harmand Treaty. In reality, Hiep-Hoa was not a great loss for us; we would not have got far with a king lacking partisans, indeed we ourselves would have had to support him by force of arms. So it was that Memen remained as king under the name of Kien-Phuc, with Nguyen-Van-Tuong and Ton-That-Thuyet as Regents. An edict of pacification was issued, and the bands were dismissed, although this did not prevent them from running amok in the countryside under the orders of hostile mandarins, and massacring a hundred Christians.

The Taking of Son-Tay

The two Regents just let this happen, but after the capture of Son-Tay they realised that it would be prudent to capture and execute the perpetrators of the massacres. These executions enabled them to make a fine show when M. Tricou arrived to revise the Harmand Treaty. They lavished him with assurances of dedication, and thanks to this diplomatic pantomime they were able to secure rather good conditions, and in particular to avoid an essential clause, the occupation of the Citadel of Hue.

M. Tricou and M. Patenôtre

The signing of the Giáp Thân or Patenôtre Treaty on 6 June 1884

M. Tricou having left, the two Regents recommenced their intrigues, but this time the game was known. M. Patenôtre arrived and imposed, as a precondition, that we should have a serious garrison installed at Hue. They had no choice but to submit. But it is evident that this last treaty of Hue was a mortal blow to the influence of Nguyen-Van-Tuong and Ton-That-Thuyet.

This very accurate account of events, we repeat, permits us to ascertain as a probability that, following the Patenôtre Treaty, the two Regents – at the instigation of China and against a background of the conflict which had broken out over the terms of the Lang-Son Convention – launched against the young Kien-Phuc the very same kind of coup d’etat which they had already perpetrated in 1883 against Hiep-Hoa, following the Harmand Treaty.

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Huế (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2018).

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group page Huế Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.

held more than 100,000 people, yet now there hardly remained 30,000. All around the palace rose great buildings constructed to accommodate countless servants or relatives, but now they were empty. In the street of the Ministries, where there once thronged a crowd of mandarins, there was little movement other than a few isolated palanquins. Meanwhile, the few advisers or servants who were retained by the new king had neither notoriety nor serious influence.”

held more than 100,000 people, yet now there hardly remained 30,000. All around the palace rose great buildings constructed to accommodate countless servants or relatives, but now they were empty. In the street of the Ministries, where there once thronged a crowd of mandarins, there was little movement other than a few isolated palanquins. Meanwhile, the few advisers or servants who were retained by the new king had neither notoriety nor serious influence.”