A train waits to depart from Dap-Cau station in 1901

There are perhaps few British merchants practically interested in the commercial development of China who are actually aware of what France is doing in Tonkin and South China in the matter of railways. There are even fewer who consider seriously the ambitious programme which M. Doumer and his supporters have mapped out for the commercial and political conquest of the region.

Paul Doumer (1857-1932)

It may be admitted that there are Frenchmen who do not hesitate to publicly question M. Doumer’s schemes, but opposition apparently exercises no restraint on the carrying out of the programme. The administration of M. Beau, the new Governor-General in Tonkin, may or may not affect French ambitions in South China, but such possibilities can no longer be an excuse for British indifference, official and commercial, in regions which we have, from our geographical advantages, complacently regarded as our own.

The British Consular officials have hitherto failed to attach to the subject the importance it merits, for occasional references in their reports to French railway schemes impress the reader with the idea that our colonial neighbours have more money than wisdom in endeavouring by such means to secure trade from allegedly barren and unproductive districts.

This impression has been accentuated by a recent speech of Lord Curzon, who, as Viceroy of India, was reported to be opposed to spending money on extending Burma railways to Yunnan on the possibility of securing trade, when such capital might be well spent within their borders with the assurance of profitable results. Such a position is undoubtedly sound, and an assured percentage of profit on capital is to an administration preferable to speculation. What Lord Curzon’s ideas are, however, with regard to the duties of the British in Hongkong and South China, is another question, and we can only gather from his published works that he is of the opinion that in commercial enterprise, pioneering work and progressive administration, it will be an unfortunate day for the British when they allow themselves to be outstripped in these matters by their foreign rivals.

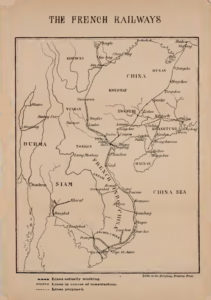

French Railways in East Asia map from Alfred Cunningham, The French in Tonkin and South China, 1902

Prince Henri d’Orleans wrote: “Why did why take Tonkin? In order to gain access into China!” The original idea of the French was to enter China by means of the Red River, but thanks to M. Doumer, that is a plan of the past: France will now enter by her railways.

It is to be hoped that the following pages and map will testify to the fact that French railway enterprise in Tonkin and South China is something more than visionary, and that although the French official may be the spendthrift that we with our commercial prejudices consider him to be, he is surely not unpractical nor unwise to squander millions of francs in simply demonstrating to the Asiatic mind the wonder of civilisation as revealed by locomotives.

M. Doumer may have had political objectives in exploiting Tonkin, and if so, judging from the results, he deserved to attain them. Curious enough, from his own remarks, it was the British railway system in Burma which served him as an example.

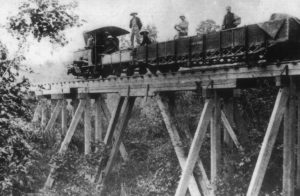

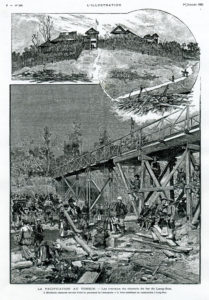

The first railway built in Tonkin was a small steam tramway running from the town of Phu-Lang-Thuong to Lang Son near the Kwangsi border. The gauge of the line was only 60 centimetres (23.6 inches) and the quaint little locomotives and small open passenger cars may still be seen in the sidings at Phu-Lang-Thuong.

A train stands at Lạng Sơn station during the time of the original 0.6m gauge Decauville military line

It was constructed by the Military to facilitate the transport of troops and commissariat during the campaign, the town of Phu-Lang-Thuong being then, as it is now, an important military centre. A few years ago it was decided to increase the narrow gauge to 1 metre; to connect the line from this town to Hanoi, the capital of Indo-China; and to extend the northern terminus from Langson to Dong-Dang on the Chinese frontier. This has been accomplished and the visitor is now enabled, by leaving Hanoi at 7 o’clock in the morning, to reach the Kwangsi border at 3 o’clock the same afternoon. A description of the journey may be of interest in showing one of the railways in operation.

Through the courtesy of Monsieur Broni, the Acting Governor-General, we were provided with a special pass and an open letter of introduction to the officers commanding the military districts; our departure was telegraphed ahead, and at one station a sergeant-major inquired for us and asked if we were comfortable.

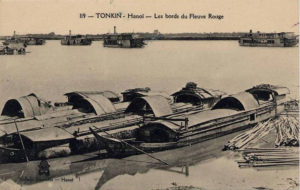

Boats on the Red River

We left the hotel at 6.30am and reached the steam ferry, which took us across the river in time to catch the 7.30am train. The ferry was a wonderful object in appearance, and consisted of an ancient and very dilapidated steam-launch with two native boats fastened to it on each side, the boats being boarded over with a platform, with side rails for protection. These were reserved for natives and their goods, chattels, provisions, buffaloes, trucks, ponies, market baskets, fish, etc, whilst the fore part of the launch was allotted to Europeans and their baggage. In charge of the ferry were two Cantonese, who levied a toll of seven cents on each foreign passenger for the trip of about one mile.

We clambered up the steep path leading to the temporary station, forcing a passage with some difficulty though the crowd of natives and their belongings, and entered the train.

An eastbound train leaves Gia Lâm station in the early 1900s

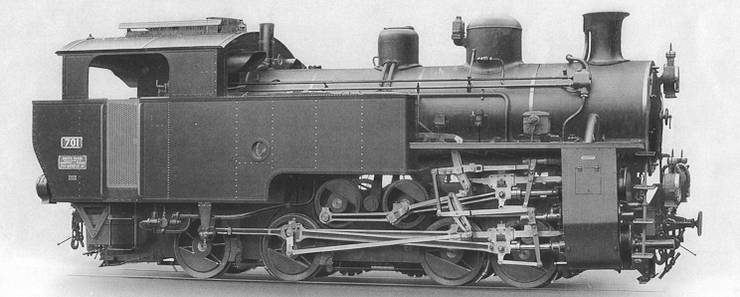

The trains are made up of about eight cars, which are divided into 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th classes. The Europeans patronise the 1st and 2nd classes, which are very comfortable, the cars being built on the Pullman model, with central corridor. The seats are comfortable and well-upholstered, and there is a lavatory. An old carriage has been temporarily transformed into a dining car, with kitchen behind, and lunch is served to those who require it for the moderate sum of $1.50, inclusive of wines. The locomotives in use are tank engines, with small coupled driving wheels and outside cylinders, and appear to be very suitable for the purpose, as the speed required is not high. The average speed on the easy gradients is 35 kilometres (21.7 miles) an hour.

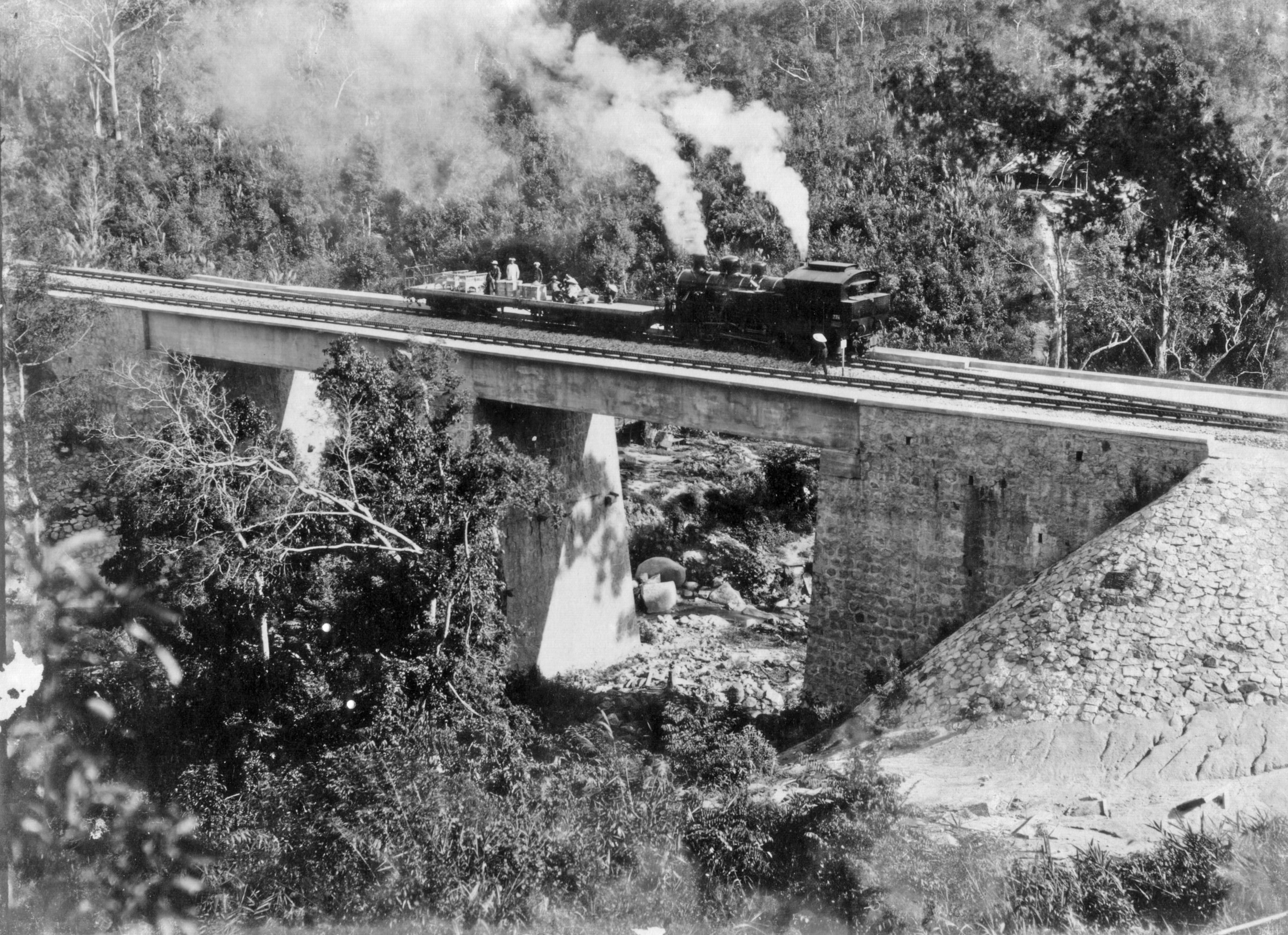

All the rolling stock, the locomotives and the bridges, are made in France. The French evidently believe in patronising home industries, as these French manufactures enter the colony free of duty. This is a very attractive policy, providing the prices are reasonable.

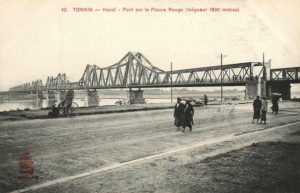

The Doumer Bridge, opened in 1902

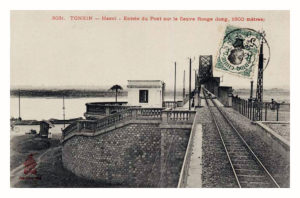

The temporary station has now been dispensed with, for the trains now cross the magnificent new bridge over the Red River. Travellers to the new terminus in Hanoi are thus saved the inconvenient journey in the unpleasant ferry.

The new bridge at Hanoi, like the one at Fujiyama in Japan, overshadows everything. It is a splendid structure, built of steel, on columns of dressed Tonkin stone, which is a kind of grey limestone. Before passing over the river, the bridge traverses for a considerable distance flat, marshy country, and continues on the other side in a long stone viaduct.

It is one of the longest bridges in the world, its total length being 1,680 metres (5,505 feet). It is designed to carry a single line of rails, with a passage on either side for pedestrians. According to Doumer’s memoirs, the engineers who constructed it were Messrs Daydé et Pillé, Creil (Oise), and the superintendent engineer in charge of its erection informed us that his task had been very difficult owing to the subsidence of the soil and the bed of the river. The earthwork leading up to the bridge had sunk three times, to a total depth of three metres, but he thought that was final.

The entrance to the Doumer Bridge

The stone columns, 14 metres high, are built up on metal cylindrical piles, 30 metres deep, which are filled with cement. There are 20 stone columns. The total cost of the bridge was 6,000,000 francs ($2,608,695), and some idea of its dimensions may be gathered from the fact that it absorbed 80 tons of paint, costing 80,000 francs, and the total weight of the steel is 5,000 tons. The bridge was opened for traffic in April, 1902. It is a magnificent work of which the French Colonial Government may well be proud, as a feat of modern engineering skill, and as a colossal monument to their desire to improve the communications between the provinces and the capital.

Leaving the terminus, the first stations of importance are reached at Bac-Ninh and Dap-Cau. At 11am we arrived at Phu-Lang-Thuong, the former terminus of the line. This is full of relics of the previous Lilliputian railway, and possesses numerous sidings, an engine shed and repairing shops.

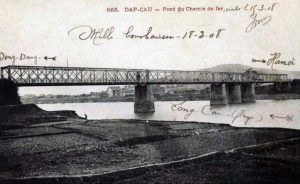

Dap-Cau Bridge

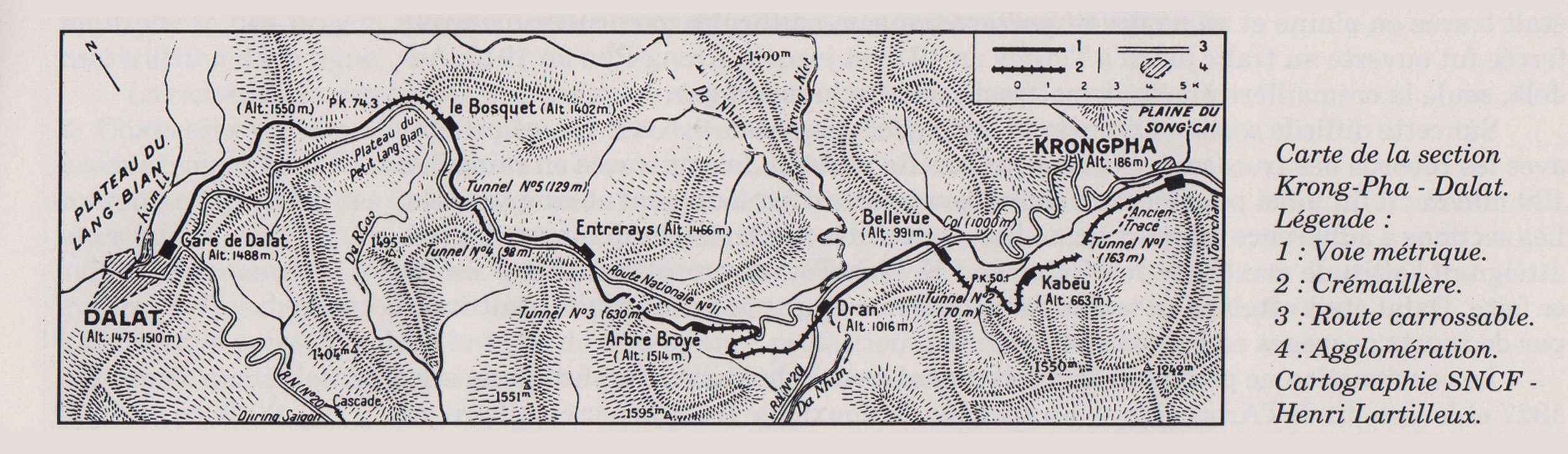

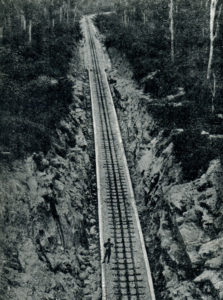

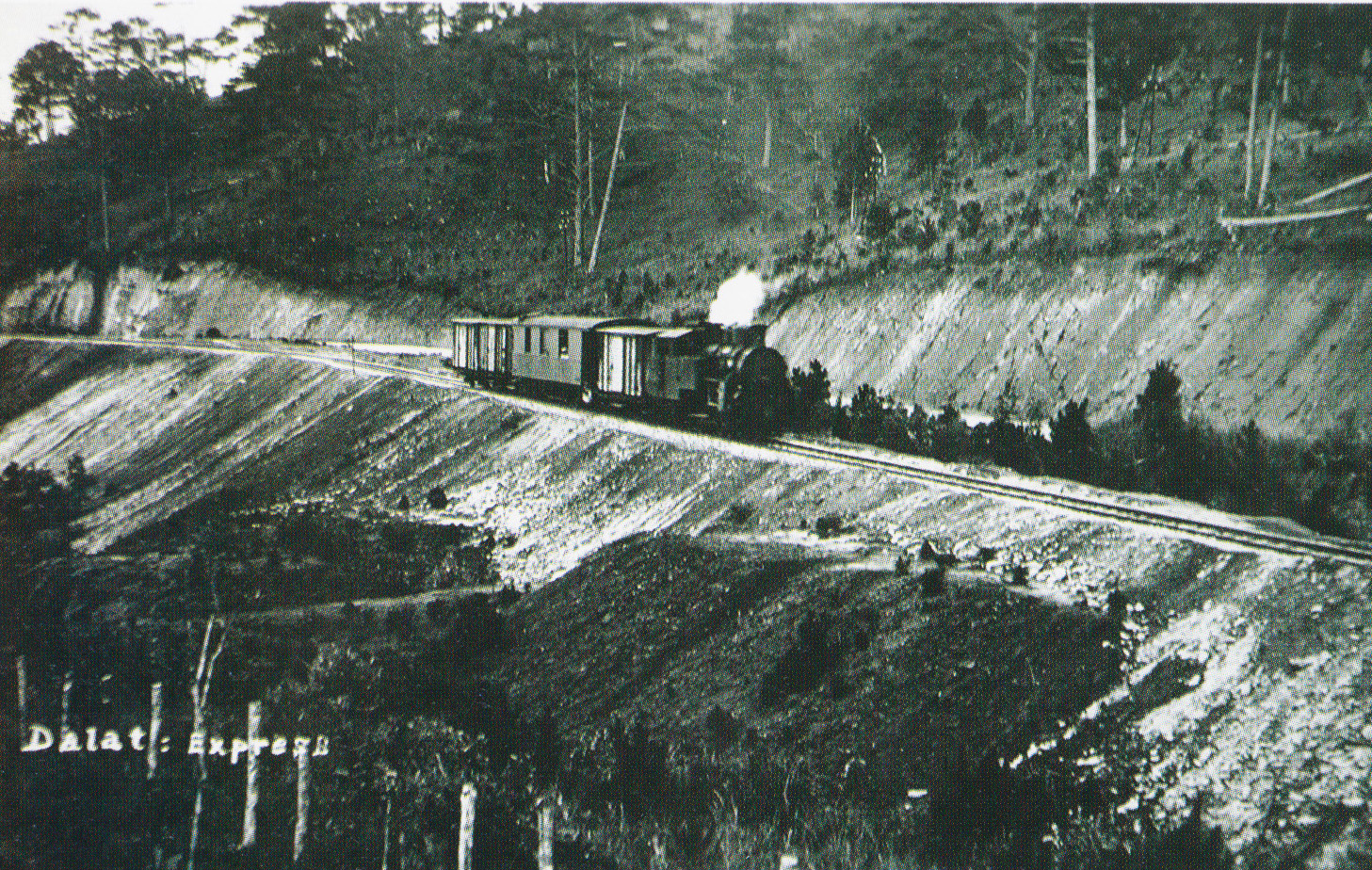

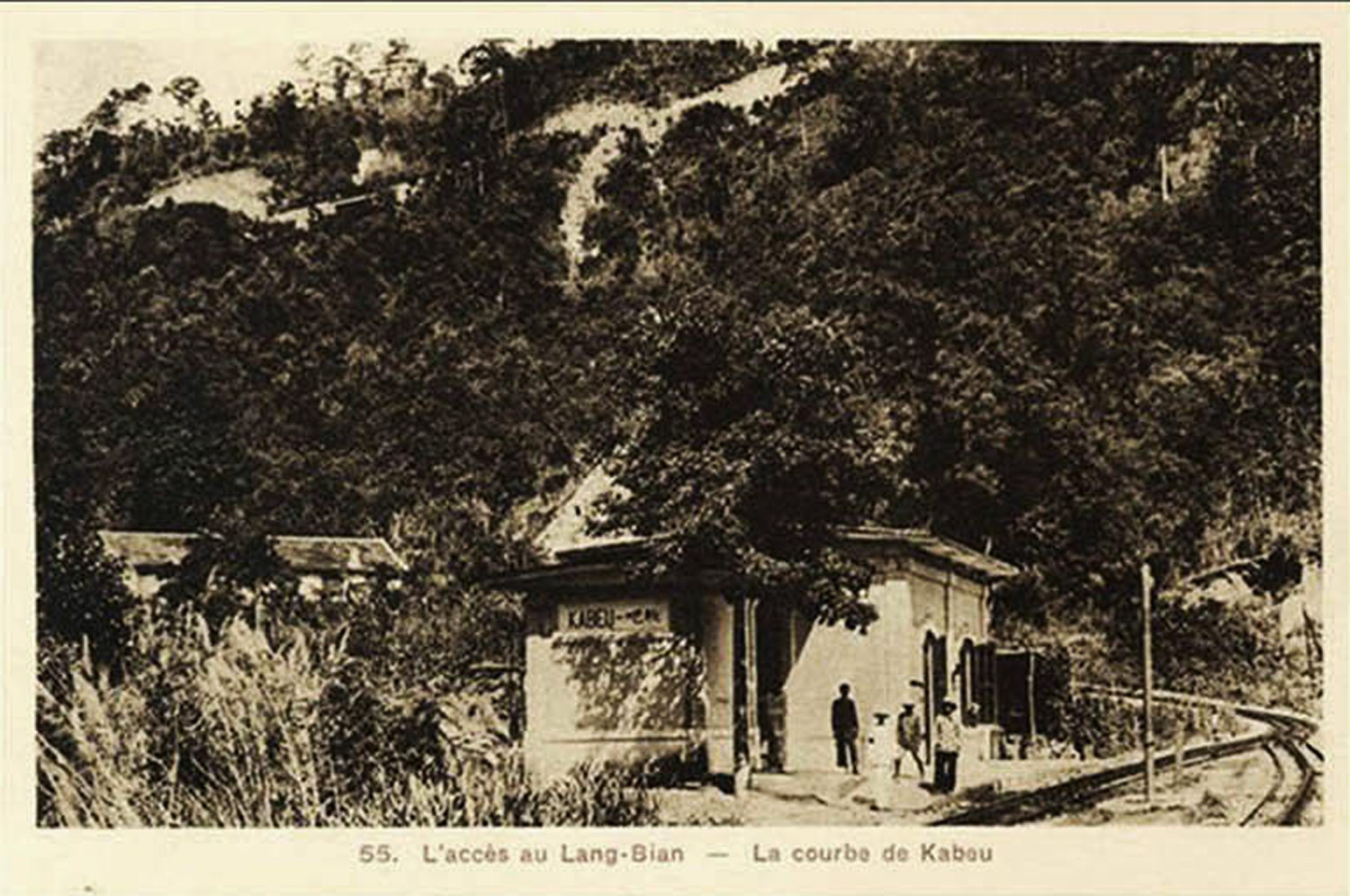

From Hanoi to some distance beyond Phu-Lang-Thuong, the country is very fertile, being one vast plain of paddy fields. As the train proceeds, the low-lying productive country is left behind and we soon reach the hills. The line has been constructed with the idea of avoiding tunnels, and consequently, once among the mountains, it is a succession of sharp curves and gradients, the train winding between the hills. The scenery is wild and beautiful. Solid rocks, hundreds of feet high, covered with foliage to the summit, rise in chains. Mountain streams overhung with trees, pretty glens, thickets of bamboo and dark woods are passed, as the little engine puffs and pants ahead, temporarily relieved when it rounds a rock and dashes down a gradient to a picturesque valley beneath. High above the surrounding uplands and valleys are built the military outstations, really miniature forts in appearance and actuality, from which float the tricolour. Overlooking and protecting every station is one of these small isolated strongholds, no doubt of great use in former days when piracy was rampant. Here and there are noticed curious large rocks, of stalactitic formation, and in numerous places are quarries worked by the Military, which supply stone for ballast and bridges on other lines in course of construction.

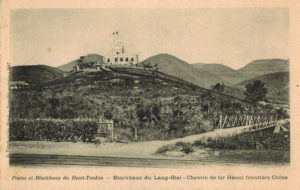

The “Blockhaus du Lang-Giai,” one of the French military posts guarding the line

As Langson is neared, the scenery changes slightly and the gigantic tree-covered rocks give place to hills almost devoid of verdure. The earth has a rich appearance and there are many indications, as in the hilly country previously passed, of former cultivation. Today, however, all is desolate. The country is practically depopulated, the inhabitants having apparently been killed or frightened away by deprivations of Chinese pirates on one hand and fear of the French on the other. Occasionally, small clusters of huts are seen, but even at the railway stations there are no villages of any size. It is said that the hills are more populated than their appearance betokens.

When Langson is in view, the country shows more signs of life and Tonkinese mingle with the Chinese, apparently on good terms. It is the ambition of the French to transport natives from other densely-occupied parts of the colony to the uninhabited hill districts, and to offer them inducements to settle.

Langson is a town of some importance, and the native population is chiefly made up of Chinese, whose quarters are on the northern side of the French settlement. The Songki-Kong River flows past Langson and enters China in the adjacent prefecture of Lung-Chow. It is crossed by a steel railway bridge 130m long.

A westbound train waits to depart from Lạng Sơn station in 1903, by Louis Salaun

Langson was a walled city with a citadel, when in Chinese hands, and then had a Chinese garrison, although nominally under an Annamite governor. There is a small French garrison stationed here. There is a good local trade done, and an aboriginal tribe called the Tho, who inhabit the adjacent western hills, sell here the course cotton material they weave. It is also the centre of the aniseed oil industry, in which a profitable business is done, the price reaching $300 a picul.

The town has been laid out in that spacious, effective way which characterises all French settlements; the roads are straight, wide and well-kept. The railway line runs through the central thoroughfare, bordered with attractive bungalows on either side. The Residency is a large, handsome edifice, and there is a spacious and well-constructed market. The railway station is an important building, with yards, sidings and outhouses, and, on the whole, Langson presents the appearance of a flourishing settlement.

Accommodation is provided at the Hôtel de Langson, and it is no exaggeration to state that we partook of one of the best dinners we had in Tonkin at the modest little hotel and cafe which overlooks the railway. After dinner the cafe presents the customary appearance, the tables being occupied by officers and the few civilians, gossiping and playing cards.

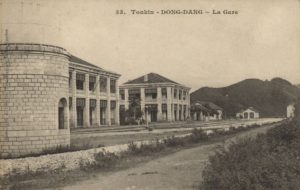

Đồng Đăng station

From Langson, the journey may be resumed to Dong-Dang, a settlement distant about 30 miles, where the present service of trains terminates. There is a garrison here of French and Tonkinese troops, who are quartered in barracks built on a hill overlooking the station. From Dong-Dang, the line has been continued to the “gate of China,” a few miles further on. A trolley was kindly placed at our disposal and we thus reached the end of the line and the limit of French territory.

A loopholed wall, connecting a chain of Chinese forts situated on lofty hills, marks the boundary, and the view is very picturesque. Hills are on every side, on top of several of which stand out clearly the grey stone forts of the Chinese, whilst a little French military station built on a smaller hill keeps watch and wards against invasion by Chinese rebel, pirate or imperialist.

The French have a concession by which the Langson line can be extended to Lungchow-fu, the largest town on the Kwangsi border, and to Nanning-fu on the West River, and they are now commencing to build the extension to those places.

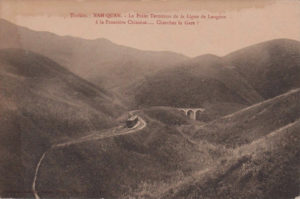

End of the line – the frontier at Nam Quan

The cost of transforming the Phu-Lang-Thuong-Langson line in 1897 from a gauge of 0.6 metres to 1 metre in 1900, and extending it from the former terminus to Hanoi, was 20,000,000 francs. Its length is 165 kilometres (103 miles).

There are 28 stations or stopping places and the rolling stock consists of 12 locomotives, 43 passenger cars and 48 waggons. There are only 17 French officials employed on the line, the stationmasters, telegraph operators, guards and engine-drivers being Annamites. The number of passengers carried monthly averages 75,000, but the goods traffic is small. The receipts amounted to $1,730 a kilometre, the total for 1901 being $263,000, against an expenditure of $210,000, showing a balance of $53,000. The native can travel 150 kilometres for $1!

Tim Doling is the author of The Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam (White Lotus Press, Bangkok, 2012) and gives talks on Việt Nam railway history to visiting groups.

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group Rail Thing – Railways and Tramways of Việt Nam for more information about Việt Nam’s railway and tramway history and all the latest news from Vietnam Railways.