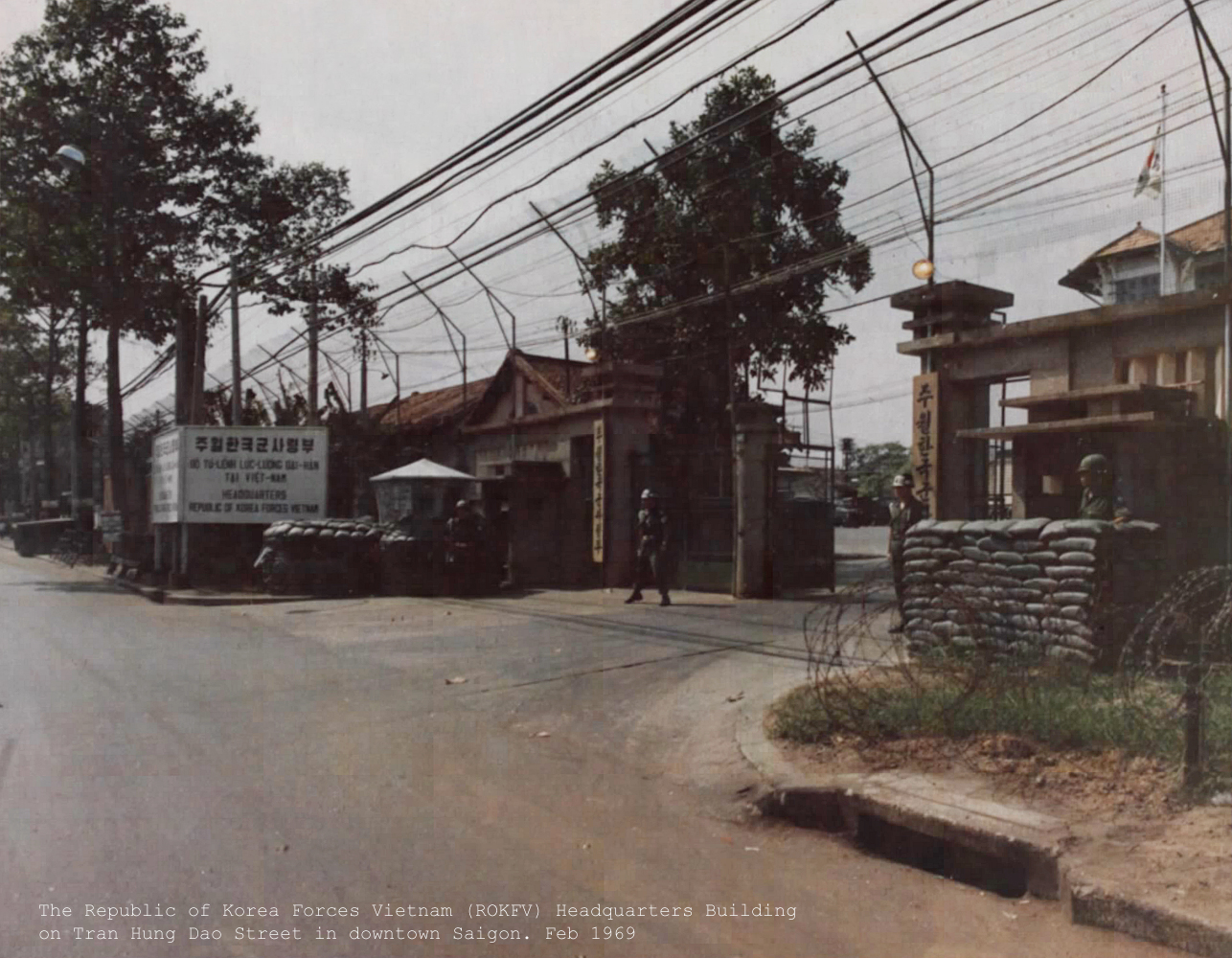

A French gunboat on the Mekong

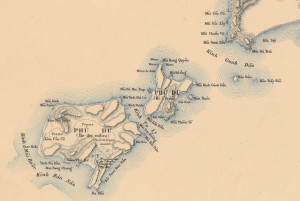

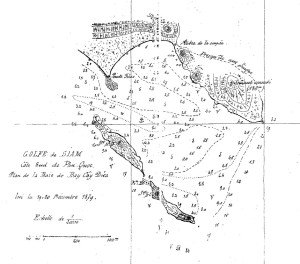

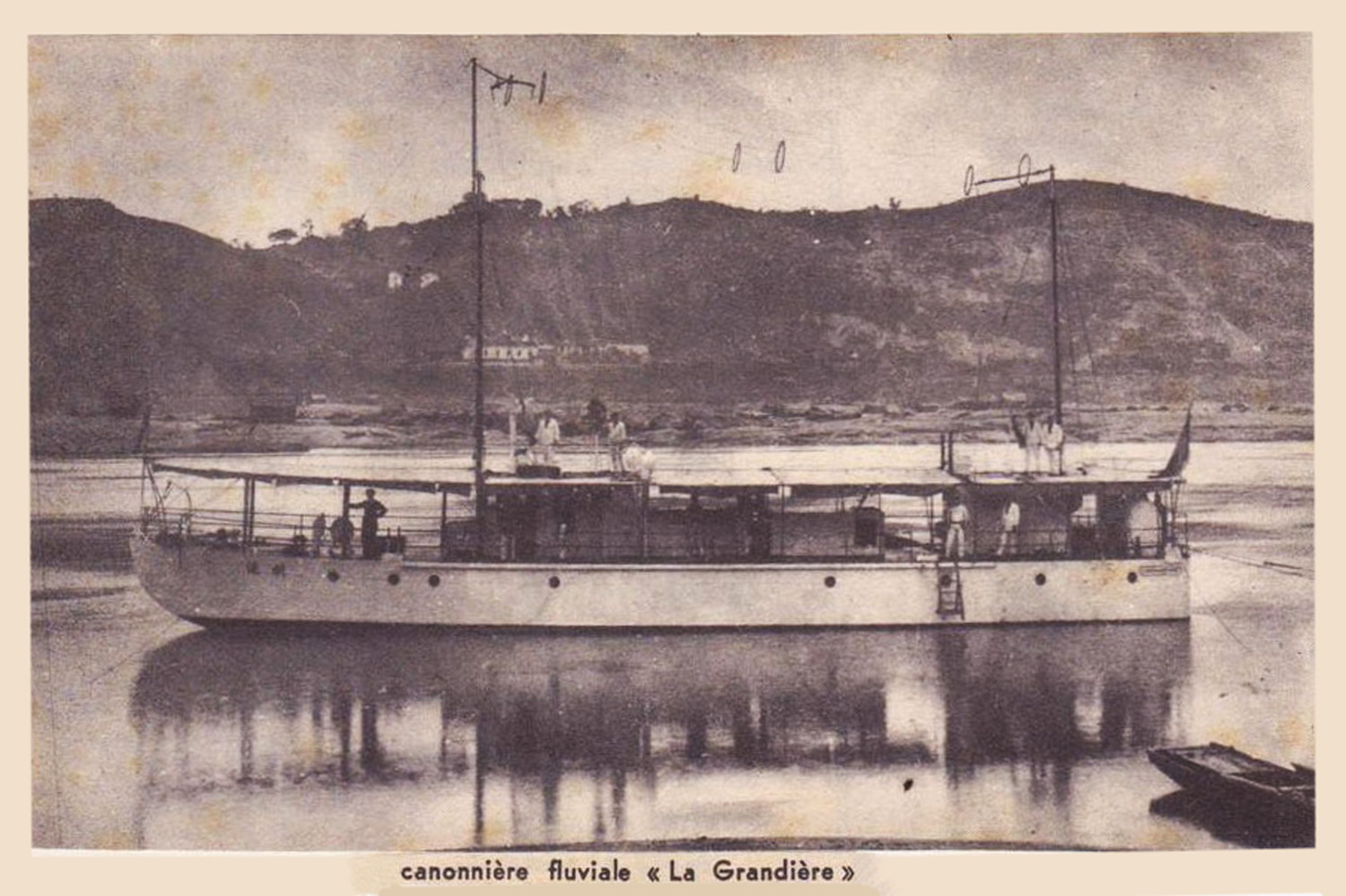

My mission to identify anchorages on Phu-Quoc was aimed at finding, along the coast of the island, a safe haven for small boats, and, thereby facilitating communications with Ha-Tien, permitting our gunboats to come here in almost any season. Years have passed without a boat from our naval station coming to Phu-Quoc; only at very long intervals could one see a small inspection craft from Ha-Tien, improperly equipped for a trip of several days.

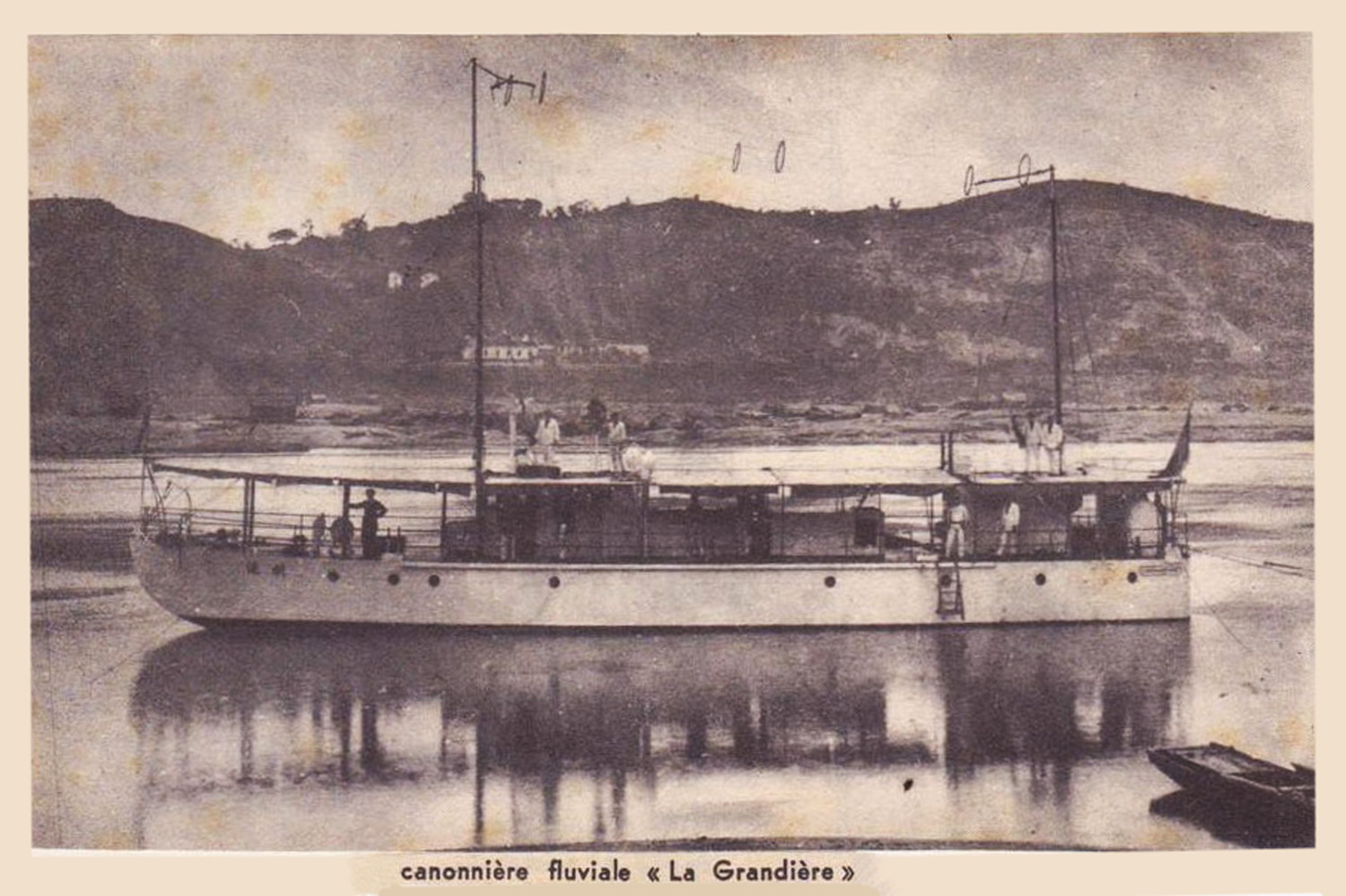

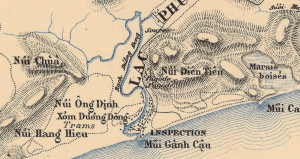

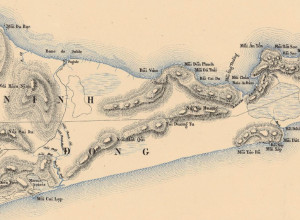

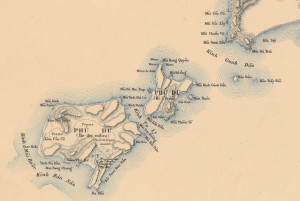

Cochinchine française, Arrondissement d’Ha-Tien, Plan topographique de l’ile de Phu-Quoc, 1897

However, the inlet which separates Phu-Quoc from the coast of Cochinchina is sheltered from both the northeast monsoon and the southwest monsoon; the sea is often calm, and the distance is only 35 miles.

We can, in most seasons, count on at least a few hours of good weather to make the journey. When, through the deepening of Vinh-Te canal, our naval vessels will be able to access Ha-Tien all year long, travel to Phu-Quoc will become very easy – once we know where to find safe anchorage.

Accompanied by Lieutenant Pitout, I left Ha-Tien on 16 December in a small inspection craft. The breeze coming from the northeast brought us to the southern tip of Phu-Quoc. I decided to start our tour of the island there; that would be our first mooring, then we would head north along the west coast, sheltered from the monsoon, and finally, with a favourable wind, we would descend quickly from north to south along the east coast, which is constantly battered by the sea and offers no shelter.

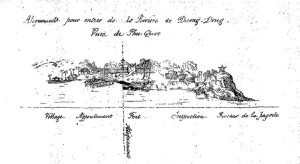

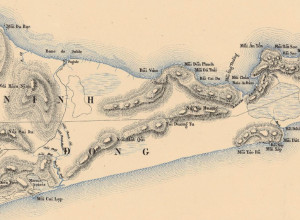

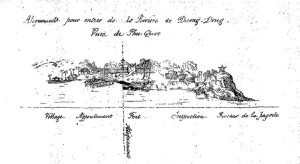

Renaud’s sketch of the Appearance of the east coast of Phu-Quoc, 6 miles off the coast in the east, abeam from Ham-Ninh

Even before arriving in Phu-Quoc, one may recognise that this is a mountainous land. From a distance, its great plateaux with sharp precipices, seemingly an extension of the great Elephant Chain, contrast strongly with the granite peaks found in Cochinchina and all the southern islands of the Gulf of Siam. Their unique appearance suggests that we are looking at sandstone mountains with porphyritic rocks, terrain made up of sandy deposits which constitute the intermediate stage in geology which evolved from primitive land of purely igneous formation (see View 1: Appearance of the east coast of Phu-Quoc, 6 miles off the coast in the east, abeam from Ham-Ninh).

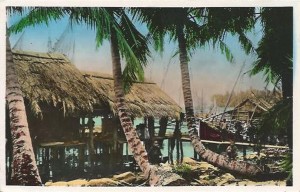

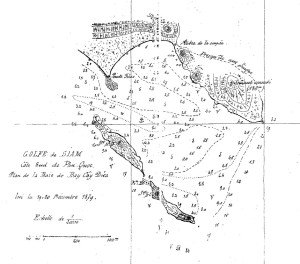

Bay-Cay-Dua – At nine o’clock, we anchored in the southern bay of Phu-Quoc; the sea was rough, but we found excellent shelter there.

The next day, the 17th, the northeast monsoon blew a real gale; despite the very heavy seas offshore, our bay remained perfectly sheltered and calm. The south coast of Phu-Quoc is completely deserted.

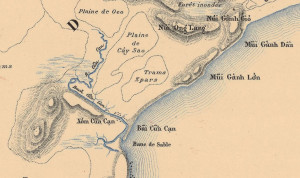

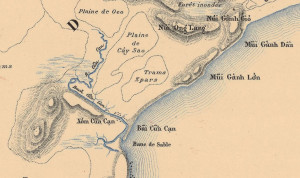

The southern tip of Phú Quốc, showing the Coconut Tree Bay, Plan topographique de l’ile de Phu-Quoc, 1897

The bay called Coconut Tree Bay has existed only for a few years. The great peninsula which encloses the bay on the eastern side (which I named Monkey Peninsula) is high, entirely wooded, and with a rounded tip, the rocky coasts leaving room for only two small beaches bordered by filao (Casuarina equisetifolia) trees. It is connected to the island only by a very narrow and very low strip of land, which, however, is not submerged at high tide, as shown on the English map.

The two islands of the west are entirely rocky, inaccessible, long and narrow, forming a good shelter against the winds and the southwest sea, which is already broken by the group of large southern islands.

The bay has a white sandy beach and there is also a small stream, where one may find fresh water.

It was on its shores that, in 1873, the plantation of M. Desgrois, then Attorney General in Saigon, was established; but today there is nothing left of what he called the “plantation Saint-Louis.” He had cleared the land and planted some coffee, of which I could find no trace.

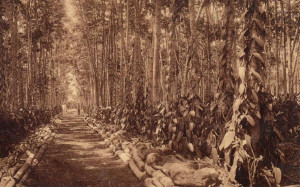

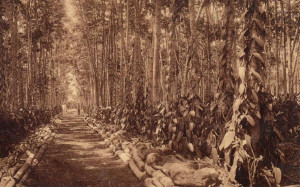

A coffee plantation

The soil is sandy, forming, to a distance of one kilometre, a plain which rises gradually to the wooded hills running from east to west, crossing the island, connecting with the two southwestern and southeastern peninsulas and rounding into a great semicircle which completely shelters the bay from the winds emanating from the north.

The seabed is very regular; a 10m deep seabed runs parallel to the beach over a distance of half a mile; during the northeast monsoon, the sea is very calm, and there are anchorages everywhere; just a short distance from the coast, one may find a seabed of mud mixed with sand, which forms a good anchor-holding bottom.

In the interior, the low mass of the southern hills leads to a square summit on the west coast, while on the east coast there is a pointed summit, near Dam. A large plain divides the island into two parts, just south of Ham-Ninh. There, one may find a small stream, the mouth of which is called Cua-Lap, which alone interrupts the continuity of the beach between the square summit and the island’s capital of Duong-Dong. This is just an insignificant stream, and one can only travel along it in a small boat; even then, one is forced to stop a few kilometres from its mouth.

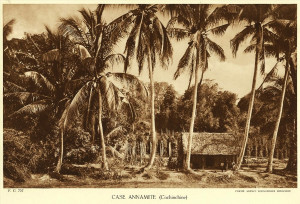

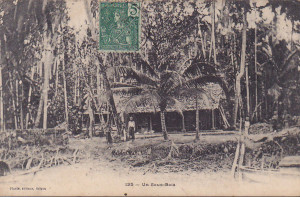

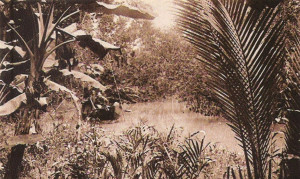

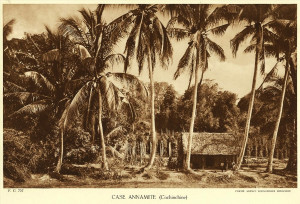

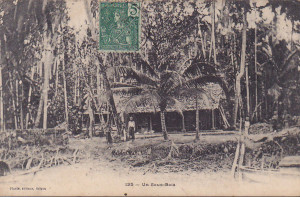

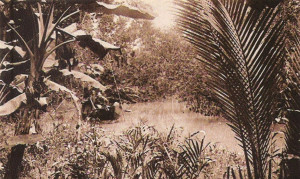

A Vietnamese house in the forest

The plains and hills inland are entirely wooded. Vegetation near the coast, constantly battered by the Gulf of Siam’s very fresh southwest monsoon, does not acquire its full development.

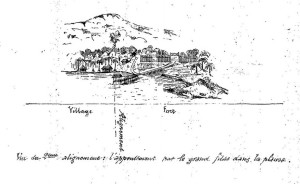

However, it becomes more beautiful as one penetrates deeper into the interior; sandy soil also becomes less pure. One only reaches the great forest after travelling some distance inland, as the hills begin to come into view. This part of the island is represented in the View No 2, taken within a mile of the mouth of the Cua-Lap.

Duong-Dong – At four o’clock we anchored in front of Duong-Dong, the capital of the island and the first inhabited place we had encountered on the coast. Duong-Dong is marked by a large black sandstone rock, visible from some distance, which lies at the entrance to the river and contrasts strongly with the white beach and the great cluster of filao trees. Viewed as a whole, the village offers a most pleasant appearance, with its houses hidden under coconut trees, and its fortress surrounded by a high fence. In front of it, next to the sea, is the former house of the administrator; at the entrance of the river, the large black rock is topped by a shrine, to which sailors and fishermen come, bringing offerings.

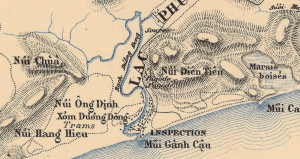

The area around the island’s capital, Đương Đông, Plan topographique de l’ile de Phu-Quoc, 1897

The river of transparent water which runs through Duong-Dong is lined with several rows of tall filao trees; behind it are three or four layers of wooded hills, leading to the highlands of the east coast (see View of Duong-Dong, taken 600m offshore, abeam from the Inspection).

The population of Duong-Dong numbers around 600 inhabitants; inside the fort resides the Huyen, who is the head of the island and has 17 militiamen under his command. The previous Inspection, built from wood, is in very poor condition; placed beside the beach, it can be a pleasant place to stay during the northeast monsoon when the sea is calm; but during the southwest monsoon it is not habitable. The Annamites never build next to the beach; all of their houses are on the river, sheltered by the first sandbank. I think that if one would like to restore the old Inspection, it would be appropriate to choose a new location.

The Annamite huts of the village, numbering around one hundred, are made from tree bark and do not have the miserable appearance of most of those of Cochinchina; the people here are all rich.

Fish sauce fermenting in tanks

The greatest resource of the country is nuoc mam or fish sauce; it is made with a small green and white fish, a few centimetres long, and nowhere is it encountered in such abundance as on Phu-Quoc. The nuoc mam of Phu-Quoc has a great reputation; it appears on the table of the King of Annam and in all the rich yamens of Canton. One makes nuoc mam by stacking the fish with salt in large tanks; after a few days, this produces a fermentation which results in a yellowish cloudy liquor, with a very strong odour, which is stored away from air and light; after 15 days, one gets the clear nuoc mam, almost odourless, which is sold in bottles. It can be stored indefinitely and does not have the repulsive smell of the fish sauce which is made in Cochinchina, notably in Phuoc-Tinh near Baria.

Fishing takes place during the northeast monsoon season; each house has a large shed where the tanks are stored; the finished product is sent to Saigon via Ha-Tien. Last year, the fish were abundant; this year, the fishing is not so good, so that the nuoc mam is more expensive. I was assured that the Annamites make, with nuoc mam, an income of around 3,000 to 4,000 ligatures each year. In 1878, the amount of nuoc mam exported to Saigon via Ha-Tien was 4,280 piculs.

Buffalos in the river

The people here do not cultivate the land and do not even have the idea of clearing space for a little garden; opposite the village is a small swamp where about 70-80 ligatures of rice are harvested each year.

Besides the nuoc mam, they also sell salted fish and turtles caught on the coast; a beautiful Hawksbill turtle may be sold for up to 40 dollars.

They also harvest resins and oils from trees in the forests.

Finally, they hunt; deer and wild boar may be found here in great abundance. Wild buffalo, from which the skin and horns are sold, abound here. In the great plain behind Phu-Quoc, the ground is literally ploughed up by their hooves. The wild buffalo of Phu-Quoc have a great reputation for wickedness; yet the danger is greatly exaggerated. At night, they travel in bands and come close to villages, where dogs utter terrible barks; they ravage all the crops, and this is one of the reasons invoked by the Annamites not to cultivate gardens. But by day, they retreat deep into the forests and are very difficult to find. Most live in herds and are not malicious; the only truly dangerous ones are the lone old buffalo; those have even been known to charge Annamites without being threatened, but happily they are few and far between.

South-central Phú Quốc, showing the fertile plain east of Dương Đông and the southeast coastal region where the Bay-Viam and Dam plantations were situated, Plan topographique de l’ile de Phu-Quoc, 1897

The danger of snakes on Phu-Quoc has also been greatly exaggerated; I was told that the Annamites dare not keep hunting dogs, because they would all be eaten by boas; in fact, this is not true, and accidents are rare. Caimans, which abound in some rivers, are much more dangerous for dogs.

The land which stretches behind Duong-Dong is a large sandy plain where the forest has been cleared; amid the bushes, and in clearings created during various ages, run many hunting trails traced by the Annamites; the over-permeable soil, formed from pure sand near the seashore, becomes very fertile in the interior, especially in the valley of the Duong-Dong river, where gardens are grown. Surrounded by high fences and each occupying an area of several hectares, these are maintained almost exclusively by Chinese and supply Duong-Dong with all of its fruit and vegetables. This is the richest area that I encountered on the island.

The river which runs into the sea at Duong-Dong is the most significant river on the island. The plan of the entry into this river was drawn up in 1874 by M. Bain de la Coquerie; it is exact in its essential parts. The narrowness of the river, and particularly the sharp bend which it forms around the sandy promontory in front of the fort, make entry very difficult.

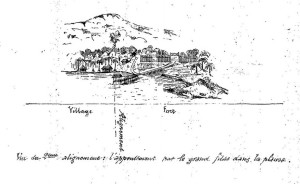

Renaud’s “first alignment” for entering the Đương Đông river

The outer channel runs first between a large bank on the west side, which extends underwater, and a promontory covered with large filao trees on the east side, then between clusters of rocks which form a line parallel to it and lead up to the large black rock near the Inspection.

I determined the alignment to follow in order to hold to the middle of the channel, which, between the bank and rocks, measures no more than 50m. It runs from the flagstaff of the fort to the extremity of the rocks at the end of the beach. One must follow this alignment to its meeting with the second alignment, which runs from the end of the pier to a large isolated filao tree in the interior; it is necessary to pass the sandy point to reach the pier. I give in my first diagram the views I took of these two alignments.

The river is so narrow that, once you have entered, it is impossible to avoid the tide. Fortunately, the current is very weak, a few tenths of a knot at its maximum speed, and the only way to operate is to do all necessary manoeuvres while being moored.

Renaud’s “second alignment” for entering the Đương Đông river

I believe that, in order to choose the best position, one should first moor the boat near the pier. On the west bank, there is a big strong tree, to which a line from the stern of the boat should be attached. That line will run close to the pier on the west side. Meanwhile, the bow of the boat should be moored by a rope to one of the coconut trees or small jetties of the village on the east bank.

To get out of the river, the best way is to send a rope to a stake placed on the tongue of sand abeam from the boat and then to haul on the stake, turning the boat while the stern remains against the pier. The width of the river between the pier and the tongue of sand is around 55m, and the sandbank is very steep.

When penetrating deeper along the river, one must moor the gunboat to the large filao trees which may be found on the second bend; indeed, the only way to forestall free movement on the water here is to attach mooring ropes from both aft and stern to the filao trees. In this operation, the first bend is too abrupt to pass directly, so in order to pass it, you must also haul on ropes fixed ashore.

The estuary at Dương Đông (A Nadal)

These are the two best points where a boat may find shelter on the Duong-Dong river; the first sand dune, the big rock and the trees all offer sufficient shelter against the offshore wind. However, if, in theory, this is possible, in practice it is very difficult; space is so limited that the manoeuvre must be made with extreme precision, for to succeed, one cannot deviate in any given alignment or arrive at a jetty at speed. The captain of a boat, before engaging the channel, must first drop anchor close to the sandbank and go to check out the estuary and the alignments and points where the boat needs to moor. In following the first alignment, one must take great care not to pass its intersection with the second: otherwise one could easily be thrown onto the rocks at the entrance to the river.

In summary, I think that the entry manoeuvre is possible, but extremely difficult; in any case, it should only be attempted in calm weather. The operation would be facilitated if we extended the pier transversely along the red line that I marked on my diagram.

From Duong-Dong to Ham-Ninh and Bay-Viam – The next day, 22 December, we walked from Duong-Dong to Bay-Viam, crossing the island by its only road, which runs between Duong-Dong and Ham-Ninh. The road is well maintained, and one could easily pass along it on horseback or in a carriage – if there were any horses or carriages on Phu-Quoc! The distance is about 25km. Leaving the fort, the road skirts the village of Duong-Dong and follows the river valley, where we encountered Chinese gardens, several rice paddies, and later the remains of an old pepper plantation which had been abandoned for 20 years.

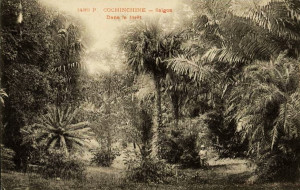

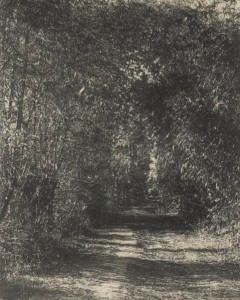

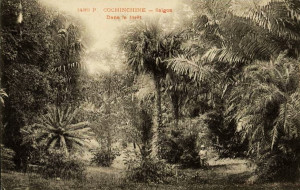

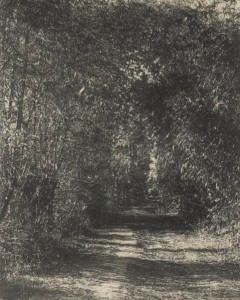

Deep in the forest

It was only after three quarters of an hour walking along this road that we finally entered the vast forest. It extends over a sandstone outcrop which, here as in all other countries, supports the development of trees; the richness of the forest floor in Phu-Quoc impresses all those who have visited the island.

The trees grow straight and tall here, slender without branches on the lower parts, their upward growth in the early years being exaggerated at the expense of their width. Here, one encounters every species of tree from our provinces of Cochinchina and Cambodia, all reaching their maximum development. The gomme-gutte (gambodge) tree is here in abundance; we shall see later what it can bring. I saw yao trees almost 100 feet high.

This beautiful forest covers almost the whole island; I also found here sandstone rocks, sometimes very ferruginous.

Half an hour before arriving in Ham-Ninh, we left the great woods to enter a field of small clearings and thickets. The soil near the east coast seems less rich; the plain is less expansive, the mountains leave little land between the coast and their very steep slopes. We encountered many tram trees [a variety of agarwood] of a very inferior oil quality, and the prairies were covered with horsetails and other plants of the equisetum family, which indicated poor soil.

Another Vietnamese house in the forest

The village of Ham-Ninh is located a few hundred metres from the coast; it consists of about 20 houses, each surrounded by a small garden cultivated with care. There must be around 100 inhabitants here; the small stream which runs through the village is only a few metres wide.

The main industry of Ham-Ninh is producing mam-rouc, a kind of nuoc-mam made with shrimp, highly esteemed by the Siamese, which is exported almost entirely to Bangkok or Kampot.

From Ham-Ninh to Bay-Viam, we follow the beach; the distance is about 7km. I find all along the coast traces of erosion; at every step, trees lie on the beach, uprooted, their trunks already far from the current high water mark. Since the start of the northeast monsoon this year, the sea has certainly advanced at least 3 or 4m.

The bay at Bay-Viam is only a temporary harbour with no shelter; one would need to anchor off the coast, because coral reefs and sandbanks obstruct the whole. It is bordered by a huge beach lined with filao trees.

It was at Bay-Viam that Messrs Girard and Coutel established their plantation, right by the sea, at the foot of the wooded hills which surround the bay. On the shore are a few workers’ houses and a small jetty just across the road from these dwellings.

A vanilla plantation

The plantation of M. Girard was the first attempt at crop-growing on a large scale in Phu-Quoc; as such, it is very interesting to visit; unfortunately, it is only 4 or 5 years old, and has thus not yet reached its full development. Only one part of the plantation is situated in Bay-Viam – the rest is located in Dam, a few kilometres further south, near the bay of the same name; the latter has roughly the same soil and topography. Messrs Girard and Coutel have planted a total of 55,000 feet of coffee trees – 35,000 in Bay-Viam and 20,000 in Dam. As yet, they are far from being in full fruit; most, it is true, have been planted for only two or three years and the harvest this year yielded only 250kg of coffee. The shrubs are planted every two metres, half sheltered from the sun under some large trees. At first glance, they seem healthy; however, unfortunately I found the presence of the “little worm” which wreaks havoc on so many of the coffee trees of Cochinchina – this is the pestilence which destroyed the plantation at Bien-Hoa, and for which we have not yet found a cure.

Next to the coffee trees sprout vanilla plants. These have still not produced anything, but they have a very beautiful appearance; At first they were given defective supports made from dead wood, onto which the stem of the vanilla stuck and was almost burned where it made contact with it. The current Annamite overseer has replaced them with small shrubs from Cambodia, planted in two rows, and whose branches formed a cradle to permit the vanilla flower to be fertilised directly.

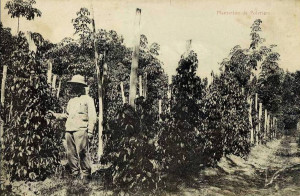

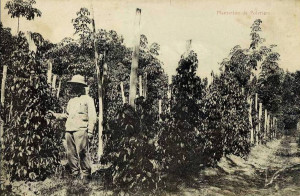

A pepper plantation

Next to the vanilla plants, 300 pepper plants also seem healthy, but are still too young to give significant results.

Finally, over a period of five years, Messrs Girard and Coutel planted 17,000 coconut trees, but many of these died, so that now there are just 5,000 to 6,000. It is hoped that, in seven or eight years, these will have achieved their full development.

Last year, they made a test harvest of gomme-gutte or gamboge. The forests of Phu-Quoc are rich in gamboge trees, especially in the regions of Bay-Viam, Dam and also Cua-Kan on the west coast. They must be grown naturally and harvested when they reach maturity. The best size for gamboge shrubs is around 7-10cm. Harvesting is done in February; one makes two spiral grooves on the trunk which meet at the lower end, so that the sap may be channeled into a small bamboo pipe. Each tree can produce annually an average of 100gms; last year, the Girard and Coutel plantation only harvested 7kg, but this is a crop that could easily be grown in large proportions.

In summary, the plantation of Messrs Girard and Coutel has still produced little or nothing; but to be fair, it has not yet acquired its full development. It is neat and well maintained, and it is, in any case, a company which sees great merit in experimenting with new crops.

I will not comment on the considerations which led the growers to choose the locations of Bay-Viam and Dam. The mountains along the coast completely shelter the fields from the breeze for 7 or 8 months, and the climate is very unhealthy, even for the Annamites. The shore, lined with coral and sandbanks, is very difficult to access; there are no communications, no resources, and finally, perhaps the most important consideration,

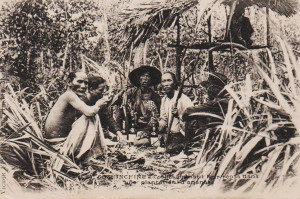

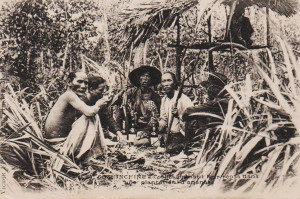

Plantation labourers taking a break from their back-breaking work

I think that the soil is less fertile than in some other parts of the island, especially the river valley east of Duong-Dong, where the Chinese gardens may be found. That, in my opinion, is the location where a plantation should have been established; it enjoys the most favourable conditions, including climate, means of communication and richness of soil.

Personnel employed in the Girard and Coutel plantation total 32 labourers, who clear, irrigate, weed and maintain the plantation. They are paid 1 franc per day, plus a ration of half a picul of rice each month. While the Annamite overseer is very smart, and, having visited Bourbon, familiar with the French style of plantation, it is nonetheless regrettable that a property of this size is not monitored by a European, or at least inspected from time to time.

The only inhabitants of Bay-Viam are the plantation workers; in Dam, there is a village of about 150 inhabitants, where, as in Duong-Dong, they make nuoc mam. I had hoped to find a good anchorage there, seeing the well-closed bay surrounded by high peaks, but once again, coral reefs hardly permit a boat to enter, and there is no fresh water there.

On this part of the coast, I found many sandstone rocks, and, incidentally, porphyry and gneiss; in times gone by, they exploited jet mines here, which are now abandoned.

A path through the forest

On my return to Ham-Ninh, I did not take the same road. Instead, I followed a small path through the interior. This trail and the road from Ham-Ninh to Duong-Dong are the only roads which exist on the island of Phu-Quoc. One passes through clearings and forests of tram trees; the soil is formed of white sand; it is indeed one of the worst terrains on Phu-Quoc; trams and horsetails grow here at will.

Bounla – After returning to Duong-Dong, we got up soon after midnight next day to head further north. We followed the coast, cooled by a light breeze from the northeast; not until noon did we arrive in Bounla. There lie the ancient construction sites of M. François, who tried, three or four years ago, to exploit the wood of Phu-Quoc. Visiting the remains of his plantation, we found no more than two or three huts for storing large pieces of wood, abandoned and rotting; they were located about 40m from the coast, near a small stream where fresh water may be had. The rafts which he used initially to transport his wood were destroyed by the sea; later, the junks he hired capsized, being too heavily loaded. In the end, he abandoned everything, and his former workshops are now in ruins. It is said that, all told, the unfortunate M François lost around 2,000 piastres.

The problem of how to exploit the forests of Phu-Quoc could be solved by building a network of roads to transport heavy pieces of wood to the coast; and, if the operation is carried out on a large scale, it would also be advantageous to have in Ha-Tien a tugboat which would come in good weather, on one or the other side of the island according to the monsoon, to haul rafts laden with wood from Phu-Quoc to Ha-Tien and Chau-Doc.

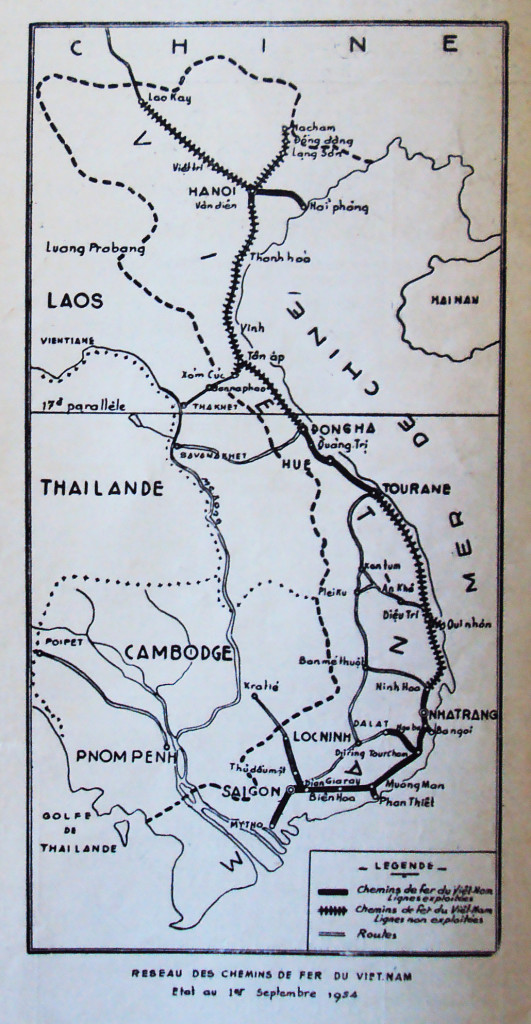

Cua-Kan [Cửa Cạn] – From Bounla, we continued our journey north by sea to Cua-Kan, where we anchored at about 3pm. A river opens at the north end of the great beach, 30km in length, which runs all the way from the square summit; at high tide there is no more than a metre of water above the breakwater.

The area around Cua-Kan (Cửa Cạn), Plan topographique de l’ile de Phu-Quoc, 1897

The entrance to the river is very narrow, but it immediately widens into a deep basin. From there, a small waterway heads a few kilometers towards the north, while the main river runs due west. It is around 80m wide, and shallow. Around 1.5kms from its mouth, one arrives at the village of Cua-Kan; It has around 150 inhabitants, all manufacturers of nuoc mam and all rich. There is no trace of agriculture, apart from some poor gardens and the few coconut trees which shelter their huts. We noticed in Cua-Kan a special type of fishing boat, very well built and very elegant. As in Duong-Dong, the people here hunt buffalo and deer with packs of dogs.

We continued up the river as far as the point where it is reduced to a trickle; thereafter, trees crisscross the waterway and there is no way to pass. This small brook finds its source in the Saint-Byoot massif, and thus crosses almost the entire island.

All of the rivers on Phu-Quoc are alike: at their mouths, they have barriers that do not even permit junks to enter; their waters are transparent, with almost imperceptible currents; and they are initially wide and deep enough for navigation, but after a few kiometres they become tiny streams which cannot even be used to transport floating timber. So we must rely on the development of roads to exploit the forests.

All of the rivers of Phú Quốc are reduced to insignificant streams just a few kilometres from their mouths

Cua-Kan seems to be established on one of the worst terrains of Phu-Quoc, whose ground comprises hard ferruginous sandstone; trees grow poorly here; one encounters many trams and shrubs, at least in the part of the river on which I travelled.

Yet, as one advances, the ground seems to rise above the sandstone layer and the trees become larger.

Around 2km east of Cua-Kan, the river makes a very pronounced bend and heads southwest. Then, around 500-600m further on, it veers back towards the south-south-east, then east again.

By the time it reaches its last bend, about 4-5km from its mouth, it is no more than an insignificant stream.

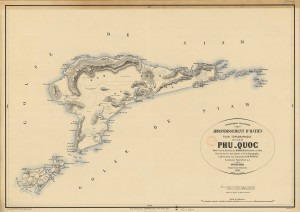

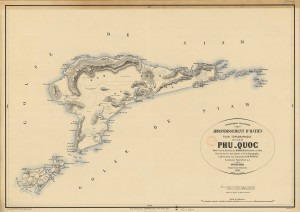

The Ile de l’Eau (Water Island) and Ile de Milieu (Middle Island) – On the morning of 25 December, we set sail to visit the islands north of Phu-Quoc, having discovered that the entire northern part of the island is now deserted, and the ancient villages of Vuong-Bao et de Bay-Doi, though still on the map, no longer exist.

The small islands of Grands-Arbres, Clump and Chenal may be seen from afar; these should not be confused with the flat rock which sits a mile off the north end of the island, poorly visible, which it is prudent to watch out for. This part of Phu-Quoc, between Cua-Kan and the Ile de l’Eau, is where the local people fish for Hawksbill turtles. The breeze is very light, and some time later we arrive at the Ile de l’Eau. Several huts giving shelter to around 20 Annamite fishermen are located near the northeastern bay. This bay is very dangerous, full of rocks and corals, and there is no anchorage.

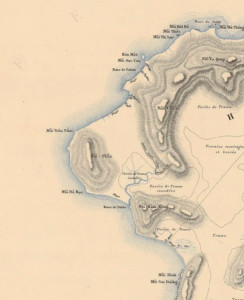

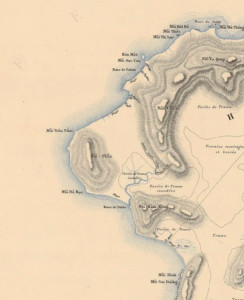

The Ile de l’Eau (Water Island) and Ile de Milieu (Middle Island), Plan topographique de l’ile de Phu-Quoc, 1897

Water Island is so-called because of the fresh water wells which may be found near the fishermen’s huts; their existence is explained by the fact that the lower layer is made from the same impermeable ferrous sandstone that I had seen in Cua-Kan, while the upper layer and the mountain on the island are made from very permeable sandstone and sand. I found pumice stone here; there are also some jet mines. As in Ham-Ninh, the inhabitants manufacture mam-rouc.

Beyond the Ile de l’Eau is the Ile de Milieu (Middle Island), which also belongs to us, and contains a few fishermen’s huts.

It’s at its northern end that the island of Phu-Quoc offers its most picturesque appearance; all of its wooded summits take many varied forms between northwestern tip of the island and the Kwala Cape, dominated by the highlands of the east, and creating a belt around the two large bays of Bay-Diem and Retram. From the left side of Cape Kwala, one may see as far as the mountains of Ha-Tien, the Kep promontory and the hills of Kampot.

To the east, the great Elephant Chain is entirely visible, while looking north, one can see the entire coast as far as the great estuary of Kompong-Som.

Bay-Diem – During the night, the breeze from the northeast lifted. We left our anchorage at Water Island and sailed to Bay-Diem, which sits in a bay, with an entrance to a river which is blocked by sand like all previous; near the mouth of that river, we found traces of an ancient village. We travelled up river as far as possible, but after just 3km it too became little more than a stream; it was full of fish; the soil seemed excellent and the trees healthy.

The northern coast of Phú Quốc, showing the Kwala Cape (Núi Chão), Plan topographique de l’ile de Phu-Quoc, 1897

The harbour of Bay-Diem, sheltered from the winds of the south, east and west, remains open to the north wind, having before it in that direction a body of water of over 20 miles, and when the northeast wind blows along the entire Elephant Chain, the sea here can be very rough.

Retram – Later the same day, we headed for Retram, located close to Bay-Diem on the other side of the Cape Kwala summit. The plan of the bay and the river drawn in 1868 by M Béhic is inexact. Firstly, he drew the river roughly twice the scale of the bay; there is little more to trust from him when one reaches the second bend, downstream from Retram. Furthermore the jet mine, which he claims is located close to the village and the river, no longer functions. To get there from Retram involves a further half-hour walk.

Retram harbour is even less sheltered from the winds of the north than that of Bay-Diem; filled with rocks and corals, it is, because of the north wind, a very bad anchorage. The Retram river is also blocked and is as narrow as that at Bay-Diem; at a distance of 1.5 miles from its mouth, we encountered traces of an old village.

Years ago, a mining operation here was granted to a Frenchman, who lost money and then abandoned it; the Annamites no longer have the right to mine for jet, and the village has disappeared.

As we reach the village, the portion of the river navigable for boats comes to an end. From there, we walk along a small path which leads to the old mine shafts, located 3km southwest of Retram. There we find four mines, flooded and abandoned; from one of them they removed anthracite. The rock in which the jet lode lies is sandstone, and right next to it I found porphyry. Jet appears in several places in Phu-Quoc; we have mined it in Bay-Doc, in Bay-Viam, in Duong-Dong, and on the Ile de l’Eau. It is highly valued by the Annamites, who use it to make bracelets and necklaces; one small jet bracelet costs 3 or 4 piastres.

An abandoned mineshaft

I brought back many samples of jet, still attached to its rock. However, I had great difficulty accessing the mineshafts, which were already overgrown with bushes and shrubs; in a few more years they will be completely inaccessible and forgotten.

Bay-Doc – We left Retram the next morning; the breeze was so light that we took 24 hours to round Cape Kwala, taking care to keep well clear of the rocks which line the northern coast of the island. South of Mount Kwala is a small stream of little importance.

To acess Bay-Doc from the sea, one must first get round the great sandbank which stretches nearly three nautical miles east from the village; only after having passed it can one turn back and enter the narrow channel which leads to the village. Even then, in a small vessel with a draft of no more than 1.5m, we had to anchor after no more than a mile.

Bay-Doc is surely the poorest village of Phu-Quoc; it sits beside the beach and is recognisable from afar by its many clumps of coconut palms. It is populated by around 100 people who produce neither nuoc-mam nor mam-ruoc. They make a living only from fishing, and the fish they catch – which includes swordfish and sharks – is mostly salted.

We arrived just as they were bringing ashore a huge swordfish, and they offered me the saw, which measured more than 1m long! The flesh of these big fish is cut into strips and dried in the sun on the wooden frames which line the beach; saws and fins are carefully stored and sold in the market at Duong-Dong.

A fishing village on Phú Quốc

Behind Bay-Doc are the highest mountains of the island, part of an entire chain which runs parallel to the coast from Mount Kwala to Ham-Ninh. The small plain that stretches west of Bay-Doc looks excellent for agriculture; but local people have not cleared even the slightest bit; they still claim that wild buffalo and deer ravage all plantations.

On the same day we left for Ham-Ninh, which we had already visited while crossing the island from Duong-Dong.

We then spent a very bad night; in the evening, the wind rose, and although we were anchored nearly a mile from the coast, the breakers were very close behind us. Fortunately, our anchors held fast, and by morning the wind had shifted to the southeast. One should abstain from anchoring for the night anywhere along the east coast of Phu-Quoc during the northeast monsoon; there is no shelter and it is dotted with dangerous reefs and rocks.

We passed again before Bay-Viam and Dam, unable to land because the sea was too rough; very soon, we found ourselves back at the southeast peninsula, our starting point. From there, we headed back to Ha-Tien, pushed by a gentle breeze from the southeast, and arriving on the morning of 31 December.

In summary, Phu-Quoc is a large, uncultivated island, apart from a few hectares of coffee plantation and the small gardens of Duong-Dong, covered throughout its whole extent by beautiful jungle which grows on a forest floor of exceptional richness and is exploitable, provided we build roads. Although its size is larger than that of Martinique, it has a total population of just one thousand inhabitants, divided amongst five villages. I did not see any Cambodians; in Duong-Dong there were a dozen Chinese involved in opium farming and garden culture. The Annamites are gentle, intelligent, very obliging, and we liked them very much.

The Customs and Excise vessel “Nam-Dinh” leaving Hà Tiên to patrol the Gulf of Siam

The people of Phu-Quoc gained a lot when we arrived in the western provinces of Cochinchina; previously they had faced the problems still experienced today by the populations along the coast of Annam, which are constantly subjected to exactions by pirates. Before we came, no junk was safe when its left Duong-Dong to go to Ha-Tien. Thanks to increased security, I was told that in the last five years the export of nuoc mam from Duong-Dong had increased tenfold, and all the producers had become rich.

However the population of this island is not increasing, since there are no newcomers; it seems that for most of the Annamites in Cochinchina, Phu-Quoc is still considered a land of exile, devoid of rice fields and fertile ground, a place where no-one would choose to go at any price.

In geological terms, the island of Phu-Quoc belongs to the class of intermediate terrain; its principal formation is sandstone, and incidentally there are also micaschistes, gneiss, porphyrys, variolites, sandy deposits, etc. Many of its rocks are ferruginous; I saw some traces of lead ore and copper, though in inappreciable quantities.

In some places, such as in the south, along the entire coastline behind Ham-Ninh in the east, and at the entry to Cua-Kan in the northwest, the terrain is made from porous sand, consisting of almost pure quartz or silica. In others, like the valleys east of Duong-Dong and near Bay-Diem, the soil looks excellent and very good for all kinds of crops.

Renaud’s sketch of the Coconut Tree Bay

During the northeast monsoon, the sea is calm on the west coast and one can anchor almost anywhere, at a small distance from land, but during the southwest monsoon, the sea can become very rough. Safe shelter cannot be guaranteed until the monsoon is well established and there is no further need to fear a change of wind.

The bay at Bay-Diem, perfectly sheltered from the winds of the south, is open to the winds from the north.

Cay-Dua Bay, of which I drew a map, seems best for mooring a small boat; it is completely sheltered from all winds, except for that from the southeast; and when the wind turns in that direction, one has the advantage of not being cornered at the bottom of the bay; the pass near the tip of the filao promontory permits us to exit the bay and seek shelter behind the two small islands of the west, which are situated behind the larger islands further south.

Practically the only river in Phu-Quoc which can be entered by a small boat is that of Duong-Dong; but access is difficult, and the manoeuvre demands such precision that it may only be attempted in very good weather and with a perfect knowledge of the area.

In these circumstances, it is certain that, if transportation was improved and the island became more heavily populated, Phu-Quoc would be covered with plantations. However, if roads are built to exploit its forests, it will also be necessary to create a proper port to which all of the island’s roads can lead. At present, there is not one inhabited point on the island to which a boat with a draft of 1.50m can come to shelter in any season.

Saigon, 16 January 1880

J. RENAUD

Engineer, Hydrographer of the Navy

Published in Excursions et reconnaissances, 1880

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebooks Exploring Huế (2018), Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (2019) and Exploring Quảng Nam (2020), published by Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.