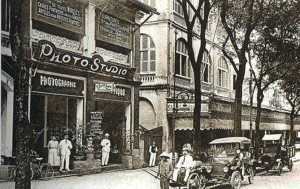

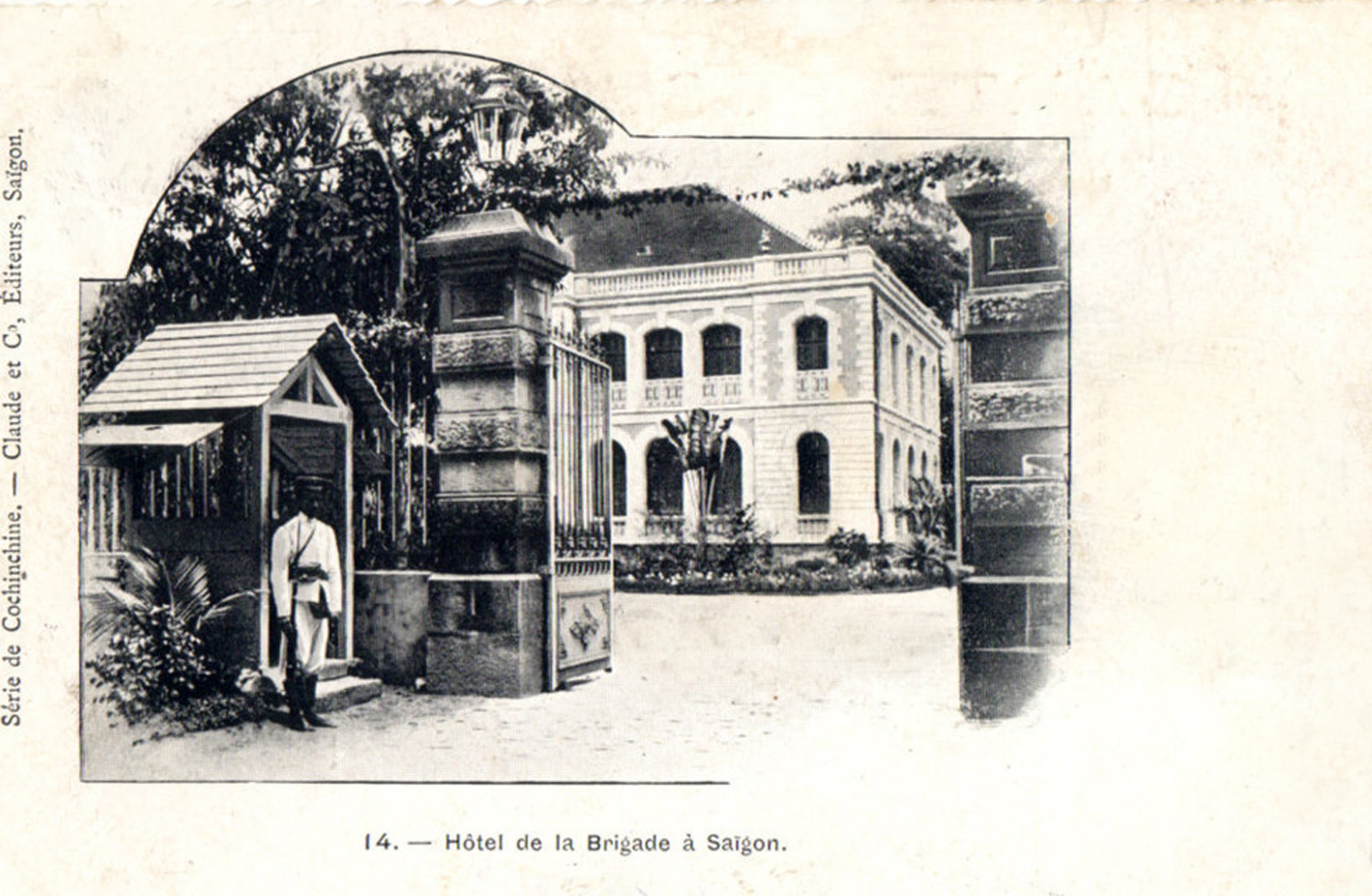

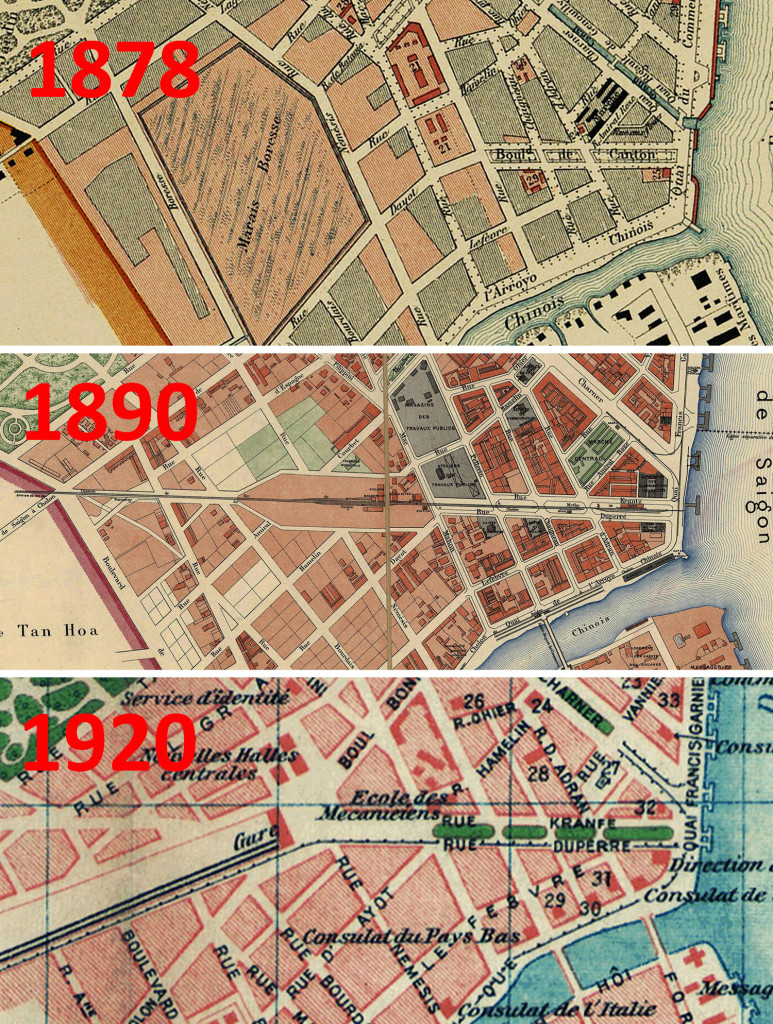

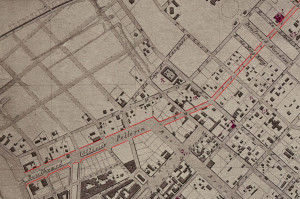

Rue Pellerin in the period 1910-1920

This article was published previously in Saigoneer.

Known for most of the colonial period as rue Pellerin, Pasteur street grew from ancient inner-city waterway into one of the city’s most desirable streets.

Pasteur street began life as part of Saigon’s old inner-city waterway network.

Pasteur street was originally part of Saigon’s ancient inner-city waterway network

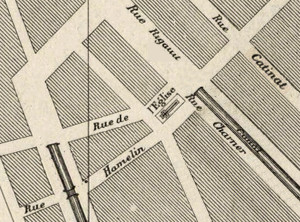

The lower end of the street was originally a canal which ran north from the arroyo Chinois (Bến Nghé creek) to the modern Lê Lợi-Pasteur intersection, where it connected with the “Junction Canal” leading east to the shipyard. It also met the “Crocodile Bridge Canal,” now the lower end of Hàm Nghi boulevard. See The lost inner-city waterways of Saigon and Cholon, Part 1 – Saigon.

Following the arrival of the French, the quaysides flanking this canal were both initially denoted as rue No 24. However, by 1863 the quayside on the west bank of the canal was named rue Ollivier (after Ollivier de Puymanel, 1768-1799, a naval officer who came to Saigon with Pigneau de Béhaine to help modernise the army of Nguyễn Phúc Ánh), while the one on its east bank was named rue Pellerin (after Monsignor François-Marie-Henri-Agathon Pellerin, 1812-1862, first Apostolic Vicar of Cochinchina).

In the early 1870s the lower end of the street was a broad tree-lined avenue named boulevard Ollivier

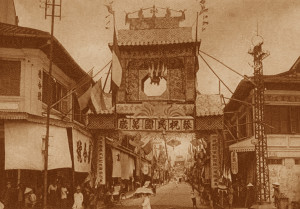

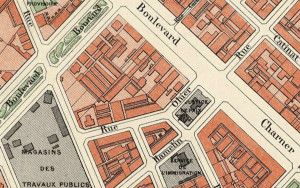

In 1868, rue Pellerin was extended north through the city as far as the rue du Marché de Tan-Dinh (now Trần Quốc Toản street, still its northernmost perimeter today). In the years which followed, long rows of shophouses were built between the modern Hàm Nghi and Lê Lợi junctions, to accommodate the large number of Cantonese settlers moving into the area.

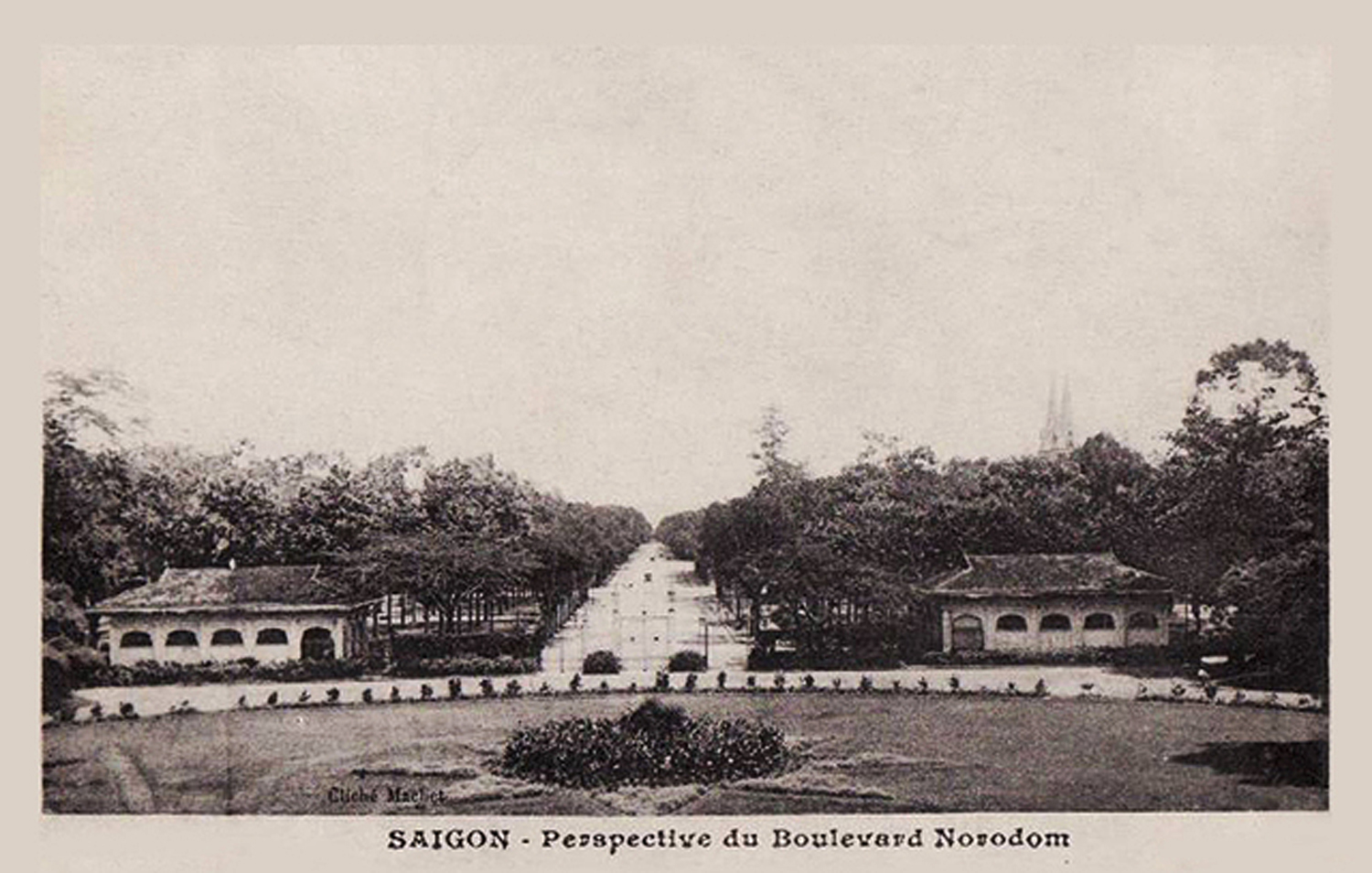

By 1870, the canal had been filled and replaced by a broad tree-lined avenue named boulevard Ollivier, which ran from the quai de Belgique (Võ Văn Kiệt) on the Bến Nghé creek as far north as boulevard Bonnard (Lê Lợi). This boulevard Ollivier survived until around 1875, when it was narrowed and became the lower end of rue Pellerin.

Eiffel’s Pont des Messageries maritimes

In 1882, that lower end of rue Pellerin was connected to Khánh Hội (District 4) and the Messageries maritimes international port area by “a magnificent bridge over the arroyo Chinois” (Notices coloniales, 1885) – today a footbridge, the Maison Eiffel’s Pont des Messageries maritimes or Cầu Mống (Rainbow Bridge) is now one of Hồ Chí Minh City’s most important historic monuments. See The “Rainbow Bridge” – a true Eiffel classic.

The arrival of the first Tamils from the French Indian Settlements of Pondicherry (Puducherry), Karikal and Yanaon in the 1880s was followed by the construction of the Sri Thendayutthapani Hindu temple on the junction of rue Pellerin and rue Ohier. See Saigon’s famous streets and squares: Tôn Thất Thiệp street. By the early 1900s, this Indian community had overflowed onto rue Pellerin, where several Tamil shops and money lending houses were established.

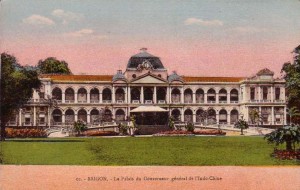

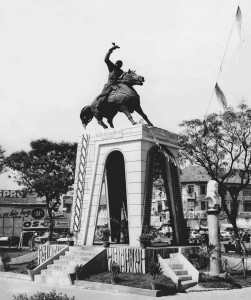

The bronze statue of French statesman Léon Gambetta, installed at the junction with boulevard Norodom in 1889

In 1889, a grand square was created at the junction of rue Pellerin and boulevard Norodom (Lê Duẩn). At its centre, paid for by public subscription, was installed a bronze statue of French statesman Léon Gambetta (1838-1882). The statue remained there until 1914 when, following the inauguration of the new Halles centrales (Bến Thành Market), it was relocated to the centre of the new public garden which replaced the former city market on boulevard Charner (Nguyễn Huệ),

By the early 1900s, the upper reaches of rue Pellerin had become a very desirable residential area, with many large villas on either side. During the 1960s, one of the grandest of these villas – 161 Pasteur – famously became the private residence of Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, President of the Republic of Việt Nam from 1967 to 1975.

161 Pasteur, former residence of Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, President of the Republic of Việt Nam from 1967 to 1975

During the 1920s, a small park was established on the west side of rue Pellerin, between the junctions of rue Testard (later Trần Quý Cáp, now Võ Văn Tần) and rue Richaud (later Phan Đình Phùng, now Nguyễn Đình Chiểu). Known from 1939 to 1954 as the square Paul Doumer, it was renamed Vạn Xuân Park (Công viên Vạn Xuân) in 1955. Before 1975, a small sports facility was opened here by the Club Sportif Phan Đình Phùng. In the 1980s the whole park was replaced by today’s much larger Phan Đình Phùng Sports Centre.

The first Pasteur Institute to be established outside the métropole was set up in 1891 within the grounds of Saigon’s Military Hospital, but in 1905 it was given dedicated premises at 167 rue Pellerin; the current buildings date from a reconstruction of 1918. During its long history, the Pasteur Institut Saigon has carried out pioneering work in many fields, including the study of parasitic, bacterial food-borne and mosquito-borne diseases, lice infestation and leprosy.

The Pasteur Institute Sài Gòn in the 1940s

Back in 1897, modern Thái Văn Lung street had been christened rue Pasteur. However, in 1955, it was renamed Đồn Đất and the name đường Pasteur was transferred to rue Pellerin, in honour of the great scientific institution located at its upper end.

After Reunification in 1975, Pasteur street was rechristened Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai, but in 1991 that name was transferred elsewhere and the old name Pasteur street was reinstated.

The Vạn Xuân Park, pictured in 1964 by Don Elsom

Surviving shophouses on lower Pasteur street today

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.