Posters for the two film versions of The Quiet American

Graham Greene’s acclaimed anti-war novel The Quiet American has been filmed twice, on both occasions using Saigon locations. While Phillip Noyce’s 2002 remake is a far more faithful adaptation of the novel, Joseph L Mankiewicz’s forgotten 1958 film nonetheless offers a fascinating historical snapshot of Saigon-Chợ Lớn in a turbulent era.

Titles from the two film versions of The Quiet American

Joseph L Mankiewicz’s 1958 movie was dedicated to South Vietnamese president Ngô Đình Diệm and starred Michael Redgrave as Fowler, Audie Murphy as Pyle and – in a rather unusual piece of casting – Italian actress Giorgia Moll as Phương. With United States Saigon Military Mission (SMM) chief Edward Lansdale acting as the film’s adviser, the story was given a decidedly patriotic twist.

By transforming the character of Pyle from American agent to aid worker, blaming the Communists for the Saigon bombings and shifting the focus from global geopolitics to the love triangle between the three main characters, Mankiewicz diluted the message of the novel, leading Greene himself to condemn the movie as nothing more than “a propaganda film for America.”

The Continental Hotel as depicted in the 1958 film of The Quiet American (© Figaro/United Artists)

The 2002 remake by Phillip Noyce, starring Michael Caine as Fowler, Brendan Fraser as Pyle and Đỗ Thị Hải Yến as Phương, was more faithful to the spirit of Greene’s novel, as a consequence of which its US release was initially delayed due to concerns that it might give offence in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.

Although the interiors in both films were studio-based – those in the 1958 version shot at Rome’s Cinecittà Studios and those in the 2002 version shot at Fox Studios in Sydney –both movies are noteworthy for their Saigon locations.

The digital version of the Continental Hotel as depicted in the 2002 film of The Quiet American (© Miramax Films)

The 1958 film delights by capturing the Continental Hotel and Terrace in all its 1950s glory, but the makers of the 2002 movie were unable to use the Continental for filming, obliging them to create a none-too-convincing digital version of the hotel – on the wrong side of Lam Sơn square!

Both films made extensive use of that square (the former place Francis Garnier), site of the “milk bar” where Fowler’s Vietnamese girlfriend Phương meets her friends every morning and later the place where a car bomb is detonated, wreaking havoc and killing many civilians.

Givral pictured before demolition in 2009 (photo credit: http://saigon.virtualcities.fr/)

The 1958 film refers to the “milk bar” only in passing, but the real-life Givral restaurant which inspired it was renovated in period style especially for the 2002 remake. Sadly, this grand old Saigon institution disappeared along with the Eden Centre in 2009, when the entire block was demolished to make way for the Union Square shopping mall.

The 2002 film omits the scene outside the “big store at the corner of the boulevard Charner” (today’s Sài Gòn Tax Trade Centre) in which Fowler witnesses one of the citywide detonations of bicycle pump bombs, dubbed by its perpetrators “Operation Bicyclette”.

Michael Redgrave’s Fowler checks his text messages at the boulevards Charner-Bonard traffic circle in the 1958 film of The Quiet American (© Figaro/United Artists)

However, the 1958 movie treats us to several views of Michael Redgrave’s Fowler standing at the “Bùng Binh Sài Gòn” traffic circle (today’s Lê Lợi/Nguyễn Huệ intersection), as well as affording what must be one of the last views of the old 1927 établissements Bainier automobile showroom before it was rebuilt as the Rex Hotel, Commercial Centre and Cinema complex.

The 1958 film also provides us with several interesting shots of Lê Lợi street, in particular the narrow alleyway at 36 Lê Lợi where Mr Heng explains to Fowler the workings of the bicycle pump bomb.

22 rue des Artisans in Chợ Lớn represented Fowler’s Saigon apartment in the 1958 film of The Quiet American (© Figaro/United Artists)

In Graham Greene’s book, Thomas Fowler rents a “room over the rue Catinat” (modern Đồng Khởi street), which is said to have been based on the Saigon Palace Hotel (today the Grand Hotel) following its 1940s conversion into rented apartments. However, neither the original Mankiewicz film nor the Noyce remake used the real Catinat/Tự Do/Đồng Khởi street as a location.

In the 1958 movie, the exterior shots of Fowler’s Saigon apartment were filmed at 22 rue des Artisans in Chợ Lớn, now the Tản Đà Hotel at 22 Phạm Đôn, District 5. Many of the movie’s Tết crowd scenes were also filmed nearby in the two blocks between Phạm Đôn and Phan Phú Tiên streets, where a great deal of the colonial architecture captured in the film may still be seen today.

Hà Nội’s old quarter was chosen as the location for Fowler’s Saigon apartment in the 2002 film of The Quiet American (© Miramax Films)

In contrast, the makers of the 2002 film preferred to use Hà Nội’s old quarter for depictions of Fowler’s Saigon apartment, resulting in some rather unlikely sequences in which the protagonists exit Saigon’s Lam Sơn square, turn the corner and miraculously find themselves walking along Hà Nội’s famous Hàng Vải amidst photogenic stacks of bamboo.

In the book, Fowler agrees to meet Pyle at the fictional Vieux Moulin restaurant in “Dakow” (Đa Kao), thereby setting him up for assassination. Once again, neither film made use of the real Đa Kao for the scene in question.

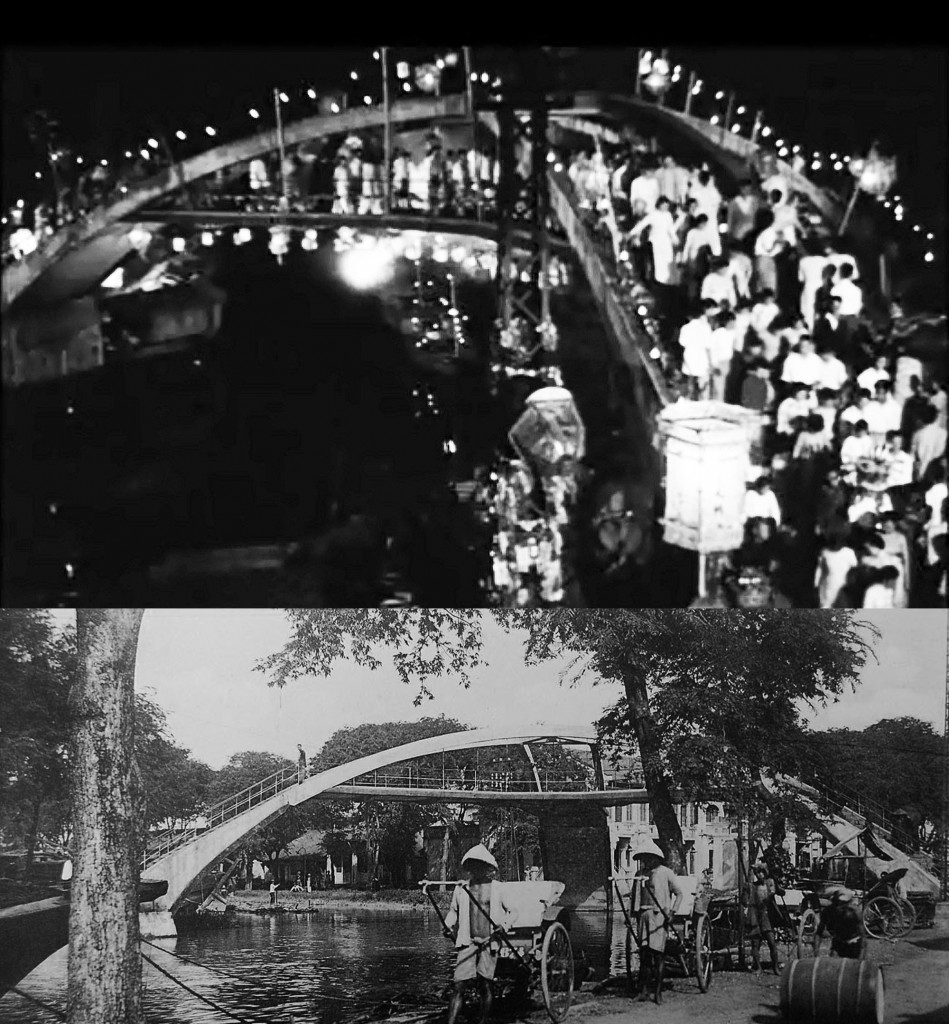

The former Pont des Trois arches (Three-arch bridge) in Chợ Lón was selected as the location for the murder sequence in the 1958 version of The Quiet American

To depict the muddy waters of the Thị Nghè creek in which Pyle’s corpse is eventually found, the makers of the 1958 film opted for the westernmost end of the canal Bonard (Bãi Sậy canal) in Chợ Lớn, at that time spanned by the famous Pont des Trois arches (Three-arch bridge). The film includes a great deal of rare footage of this unusual Chợ Lớn landmark, which was built in 1920 by the établissements Brossard et Mopin with funding from Minh Hương businessman Trương Văn Bền (1883-1956), owner of the highly successful Xà bông (Savon) Việt Nam soap company. The bridge was demolished in 1990 but is still recalled fondly by many older Chợ Lớn residents.

Hội An was chosen as the location for the murder sequence in the 2002 version of The Quiet American (© Miramax Films)

Meanwhile, the 2002 film unexpectedly transports us to Hội An for the murder sequence, substituting the Cẩm Nam bridge over the Thu Bồn river as the location for Pyle’s demise.

Since Phillip Noyce shot his Tây Ninh sequences entirely on location in Ninh Bình province, the Cao Đài Cathedral – described vividly by Greene as “a Walt Disney fantasia of the East, dragons and snakes in technicolour” – is conspicuous by its absence from the 2002 movie.

Michael Redgrave’s Fowler tours the Cao Đài Cathedral in the 1958 version of The Quiet American (© Figaro/United Artists)

In contrast, the 1958 film includes an extensive sequence of archive footage shot in Tây Ninh, which depicts Cao Đài pope Phạm Công Tắc (1890-1959) presiding over the annual grand ritual dedicated to the Đức Chí Tôn (Supreme Being) and reviewing what Fowler describes as his “vigorous young Caodist army of 25,000 men.”

In recent years, the 1958 Joseph L Mankiewicz version of The Quiet American has been largely forgotten, while Phillip Noyce’s excellent 2002 remake has rightly become required viewing for Hồ Chí Minh City visitors who are seeking to brush up on local history.

Yet despite its many shortcomings as an adaptation of the original novel, the fact that all of its location shots were concentrated in and around Saigon makes the much-maligned 1958 movie a unique and fascinating visual record of this city during the turbulent period in which it was made.

You may also be interested to read these articles:

Graham Greene’s Saigon

Saigon on the Silver Screen – The Lover, 1992

The Continental Hotel Terrace pictured in the 1958 film (© Figaro/United Artists) – and the same location today

In the 1958 movie (© Figaro/United Artists), the exterior shots of Fowler’s Saigon apartment were filmed at 22 rue des Artisans in Chợ Lớn, now the Tản Đà Hotel at 22 Phạm Đôn, District 5

The 1958 movie (© Figaro/United Artists) affords what must be one of the last views of the old 1927 établissements Bainier automobile showroom before it was rebuilt as the Rex Hotel, Commercial Centre and Cinema complex – today the 5-star Rex Hotel

Mr Heng explains to Fowler the workings of the bicycle pump bomb at 36 Lê Lợi in the 1958 film (© Figaro/United Artists) – and the same location today

The famous Pont des Trois arches (Three-arch bridge) in Chợ Lớn was chosen for the murder sequence in the 1958 film (© Figaro/United Artists)

The spot where Pyle’s corpse is found floating as depicted in the 1958 film (© Figaro/United Artists) – and the same location today

Tim Doling is the author of the guidebook Exploring Saigon-Chợ Lớn – Vanishing heritage of Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2019)

A full index of all Tim’s blog articles since November 2013 is now available here.

Join the Facebook group pages Saigon-Chợ Lớn Then & Now to see historic photographs juxtaposed with new ones taken in the same locations, and Đài Quan sát Di sản Sài Gòn – Saigon Heritage Observatory for up-to-date information on conservation issues in Saigon and Chợ Lớn.